Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The article below forms part of Mike Alfred's series on Joburg personalities from the first decade of the 21st century. Click here to view Kathy Munro's fantastic introduction and here to view the series index. The stories were written in 2005/6.

I meet and talk to Frans Beleni, a senior official, his title is Production Pillarhead, with the National Union of Mineworkers. He works at Union headquarters, 7 Rissik St, an Art Deco building opposite the old SARS. His lifespan embraces the old South Africa becoming new. His forty five years have been packed with protest, change and emergence.

NUM Building Rissik Street (The Heritage Portal)

Blue plaque on the NUM building (The Heritage Portal)

Beleni, not a born Johannesburger enjoys and values its many amenities but is perturbed by the crime. He became a young activist at school, and later a fugitive from the police. This was followed by a period as a miner on the Free State Goldfields, which provided him with both ‘a convenient place to hide’ and ultimately, his life’s work. While employed as a miner he joined the Trade Union and for his organising activities he was eventually sacked. Then he was offered a full time union position. He rose quickly up the ranks. It may not be an exaggeration to suggest he took to administrative leadership like a duck to water.

Today he’s an executive with a portfolio covering training and development, health and safety and collective bargaining in the economic sectors, mining, construction and energy. It’s a big job and in this post apartheid world, an increasingly sophisticated job. He’s a busy man, observing tight schedules. He’s modest, he communicates precisely and economically. In a business he’d surely be sitting on the board. In fact, as a non executive director he sits on the boards of several corporations including Escom, Naledi [Cosatu’s training arm] and Rand Mutual Insurance. He views the country’s challenges with a broad appreciation and perspective. He’s courteous and very self-contained, he doesn’t overtly communicate the passions underlying the accelerated trajectory of his life. This is his story:

‘My name is Frans Beleni and I was born in Trompsburg in the Free State Province. I lost my mother quite early, when I was five years. My father then asked a family member, an uncle, to take care of this young boy. So they adopted me and I grew up with them as their child to this day. Schooling was a little bit difficult in the Trompsburg area, because we only had schooling to standard six. After that we had to go to the city, Bloemfontein or the Homeland, Qua Qua. But I had to work; there wasn’t enough money, so I worked in gardens, working for white people. I remember once this lady said to me in Afrikaans, “When you’ve finished I’ll give you a piece of bread and a jug of coffee.” And I couldn’t say no. I wanted money, not coffee and bread.

‘I became an activist because one struggled at a personal level; poor schooling, earning little money in gardening. I could see there were two worlds. I realized that as a black, I was disadvantaged compared to the white boys I played with. Politically it was difficult to organise ourselves. But moving out of Trompsburg, going to high school, that’s where we were exposed to the student movement and the fight against Afrikaans as a medium of instruction. For me, the most powerful influence, although there was no direct interaction, was Madiba. He was our hero, we worshipped him. By the time I discovered the reality, this man was in jail and still fighting for us to be free.

‘I moved to work in a construction company, Imprefect, Savage and Lovemore, for a year. They were building a road between Harrismith and Qua Qua. We worked and lived in a camp on the side of the road. I raised enough money to go back to school. And I found a school in the Eastern Cape, Abambo High School near Whittlesea, 100 kms from Queenstown. My early stay in the village of Mcemba where Abambo High School was situated, was not easy at all. A man who worked with my uncle on the railways referred me to the school, and he also claimed that he had arranged a room for me to rent. On arrival at Mr Tyutu’s house I was told there was no such arrangement. But they allowed me to stay in a wooden shed used to store cattle food. The gaps between the planks of my new home were so wide that I could see people passing by on the street. The winter was so cold; I had only one blanket. For the first six months my daily meal was either, milk, bread or tinned fish. Occasionally I visited friends who would prepare me a cooked meal. Mr Tyutu ran a store called Sheila’s General Dealer. I befriended the last born of the family, a young girl called Vuyelwa. She would steal money from the shop which she gave me as pocket money to survive. After the first school recess Mr Tyutu realized I was a ‘nice boy’ so I was invited to stay in the main house where I shared a room with the only son, Toto, who passed away in 2003.

‘At Abambo High I had to study in Xhosa not Sotho. They were laughing at me because I couldn’t write Xhosa and my spelling was terrible, but I managed to pass. We then got involved in student activities there. There was a man in Queenstown, I don’t remember his name, he’d spent time in exile, also underground, we had code names. He would speak to us in the evenings. He presented things to us, he was like a witchdoctor, he held us in a spell? He helped us articulate our grievances, we started to see the naked truth. It made us angry and gave us the energy to say, “We have to go through this!” Some of us wanted to leave the country, but he said, “Stay and fight here!” We boycotted lectures. And then the school was burned. The school committee was angry because the school had been built by the parents. They considered that the ‘foreign’ students, not their own, were making the trouble and we should be expelled.

For me to leave the school was a painful decision to take. At the time I had a free bursary, offered to me as a top performing student. The terms were that one had to write every exam, failing which the bursary was lost. I left before I could write matric.

So at that stage, because of our activities, the police were looking for us as well and we had to run away, literally. That was in 1978 when I was eighteen. I shuttled back and forth, some times I went home. I learnt that that I was on a police list. A friend advised me to leave my hometown; it was too small, I could be picked up easily. He told me to come to Welkom which was much bigger, safer, easier to hide. I went to Welkom in 1979. There I looked around the mines’ hostel system, the mining system. This seemed to be a nice place to hide, because ‘these people’ are all around, there all the time [laughter]. So then I went to establish how could I get into mining? They sent me to Bloemfontein which was my area, to fill in the forms for employment. I chose to work at Welkom Mine which was close to the township; I could walk to see my friends. But basically, I didn’t want to be a miner, I was hiding in the crowd, keeping low.

‘My qualifications of standard nine allowed me to ask for a surface job but my Personnel Assistant, the man who processed my papers, entered standard six, so I had to go underground. I think he was envious that I had higher qualifications. He told me I’d have the opportunity to work on the surface later. The most painful part was where you were acclimatised to work underground. You stay in a room at 40 celsius for eight hours, with a few breaks for water. And this went on for a week. Some of us, the township boys who didn’t normally seek employment on the mines, left right there; they didn’t complete acclimatization training because it was very tough. I realized that if I quit I’d have to go back home and I’d be in danger so I completed the programme and then I went underground.

‘Normally new workers are called novices but my PA entered ex-leave. In other words they thought I was experienced. Normally novices start off in the haulage where there’s ventilation and so on, it’s cool and light, easier. And they keep you there until you get used to the environment. But because I was ex-leave, they started me right away at the stope. And working, I had to work on my knees there, it was such a scary thing for me. They gave me a shovel to clear the rock. Others would fill the shovel but I’d take only one stone. The team leader got very upset with me, he said, “How can they send such an inexperienced boy to me?”

And it was very hot. The other miners were taking snuff because they could not smoke underground and they were spitting into the drinking water and I didn’t like it. I went to the passage to get fresh water to drink. A white miner was sitting there in the waiting place eating his bread.

“Where are you going?”

“No, I need fresh water.”

“You’re not allowed to leave your work station.”

“But I need water.”

“The hell, go back.”

I had to go back without fresh water. I forced myself to work without drinking at all.

‘After the shift I went back to the PA and said “I resign, I can’t stand this.” He said, ”No, no, no, I’ll sort this out, I’ll make a plan. No, don’t resign, you’ve got a very good Marabaraba [intelligence] test, you scored the highest. Your chances of promotion are high.” But the next day the same Team Leader collected me. Finally on the third day they sent me to another section where I was handling equipment supplying the stopes. It was slightly better.

‘Coming now to the hostel environment, it was strange for me coming from a township background; I spoke most of the languages and there was not much about tribalism, people weren’t interested whether you were Xhosa or Sotho. We learnt many languages in the street, it came naturally. In the rural areas you won’t find the same situation. Other tribes are unusual. I remember being told about people in the Transkei flocking to see a Pedi [Northern Sotho] boy who was visiting a family. People paid five cents to see him. It was like a freak show; they’d say things like,”laugh, Pedi boy.” So in the mine hostel, the first thing people would ask me, they never asked me my name, it was, ”What tribe do you belong to?” I didn’t like that, it irritated me. I wanted to tell them,”hey, I’m Frans, I’m a Xhosa, a Sotho all these.” I was working at an Anglo mine and they no longer divided people by tribe but people still asked. But the other mining groups, they still used that tribal system.

‘And also by that time on Anglo mines, accommodation conditions had improved. We were sleeping eight in a room divided in the middle; four on the one side and four on the other. As a new comer I had to sleep on the top part of the “double bed.” I was a youngster, I was shy in front of people, it was strange. I was never sexually harassed, but people made comments in the shower. You’d hear remarks and you’d realize they were directed at you. But there was an element of fear for a township boy. They’d be known to be fighting with a knife and so on. So that helped, even though I’ve never been a violent person.

‘One of the things I really hated was the control in and out of the hostel. We had to wear a permanent armband with a number on it. They were three different colours; white for surface, yellow for underground and red for working in very hot conditions. At first I knew nobody in the hostel but I had friends in the township and I visited them when I was off. I hated the armband because it distinguished me from my friends. But what we youngsters did, we stretched it in hot water and coke so we could take it off. That armband cost me a love relationship.

‘I had a girlfriend in the township, Thabong Township and I lied to this girl. I said I was working at OK Bazaars but in the warehouse where she could not visit. I didn’t wish to tell her I was a mineworker. Perhaps she’d label me. I had to push myself as relevant and I lied. When I went to see her I polished my shoes, they shined, I was neat, I had my handkerchief, put my armband in my pocket. It was the first time, we met formally and we kissed; after we kissed I took out my handkerchief and out fell the band. I just took it and left. I didn’t give her an opportunity to call me a liar. I realised I was exposed and I left. I hated that armband system. It cost me a girl friend. I hated it!

‘Hostel food, I didn’t like it. What we would do, we ended up buying a Primus stove and an electric hotplate. We’d organize our own sugar, tea, bread and peanut butter, and we did our own cooking, cooking our own meat and so on.

‘Over time I established friendships with people from different parts of South Africa, also from Lesotho. We were youngsters in the same age category. It was interesting to get exposed to different cultural activities; Shangane dances for instance. I didn’t know those things, it exposed me to a wider world. I saw how other people made themselves happy.

‘I progressed; I got quick promotion. I was made to do different jobs in a short space of time to qualify for a supervisory position. Over an 18 month period, I did winch driving, machine drilling, loco driving and then I was appointed supervisor. They call it a Gang Supervisor. Yes I had the potential. I was educated, standard nine, others were getting clerical positions with standard six. I scored high on the Marabaraba. I was a supervisor when the union was formed in 1982.

‘I remained an activist throughout. I was involved in the UDF structures and so on. Not on the mine, but in the township. On the mine I was thinking, why don’t we get organized? Racism and discrimination were so naked, a daily occurrence, people would be assaulted with no recourse. And a terrible part was accidents. One, I shall never forget in my life. It involved a fellow from Malawi. I knew him very well. After work he would do tailoring, sitting outside with his machine. He was a team leader. That fellow, oh, I get so emotional when I think of it, that fellow was hit by a winch lock which broke loose. It smashed his head, his brains were in pieces, all over, you couldn’t recognize his face.

‘In those days one didn’t know much about enquiries and things like that. What happened was the shift boss came, we collected the pieces of brain, put it in a plastic, and the body was taken out. What happened then I have no clue. That was the last we heard of it. It was the most scary accident I saw. If I hadn’t been dismissed I would have left the mine, because after that, it wasn’t easy, going underground.

‘The other accident that I witnessed was a fellow who was a machine driller. A rock pillar collapsed on him. You could see the blood coming out of his ears and mouth. After that I was so emotional I could not work. Other people talked about it in the lift, “Oh so and so, that machine driller died.” And that was that, it was over for them, but it affected me deeply.

‘In the union, because I was a supervisor, I preferred to be an ordinary member. I didn’t want to take a leadership position, but because I could read and write, because I was communicating and involved in recruitment in the hostel, I was elected as a shop steward. I’ll say that Anglo American was not anti union. That’s where the union entry point was, Anglo, before the other mining companies. Recruiting inside the hostel was no problem. A directive came from head office that the union was recognized. The problem was with Rand Mines, JCI, Anglovaal. At Anglo American there were individual attitude problems but not from a policy point of view.

44 Main Street, Anglo Head Office at the time (The Heritage Portal)

‘Then I went up the ranks, I became a shaft secretary. There were various actions which we mobilized, but the big one was the 1987 strike. Our branch played a key, a central role there in the Welkom area. And management did not like it. I was a target and then we were all fired, 50 000 workers. And then, after the settlement, we were given back our jobs. I was appointed branch chairman. Then Anglo was bad; they came up with all sorts of conditions to make us submissive. They made people fill in indemnities, they restricted meetings, no union T shirts allowed. In 1989 the Government passed the Labour Relations Amendment Act. Cosatu wished to organize a strike to protest against it and I made a major mistake. I went out trying to mobilize workers to strike. I was addressing workers at No.5 Hostel and I was not aware that my words were being recorded.

‘They used the recording to charge me. I thought I was just speaking my mind. Normally we were charged by our immediate supervisor but my case was handled by the General Manager and the appeal was heard at Anglo Regional level and I was fired. Pamphlets were placed in the entrances to all hostels with my photo, saying I was persona non grata, not allowed on the premises, and that if anyone sees me, he must call security and I must be removed. That’s when my formal employment ended but Cyril Ramaphosa, then General Secretary of the National Union of Mineworkers called me, interviewed me and said they’d appoint me as a Regional organizer. I had met Ramaphosa when I was part of the wage negotiations team talking with the Chamber of Mines. I started in the Welkom area and the General Manager wrote to Cyril saying it was digusting that someone he had fired had then been appointed organiser. [laughter]. Fairly soon I was promoted to a regional position and later I became an Area organizer responsible for the Free State, Welkom and Carltonville areas, reporting to the National organizer. Later it was decided that all the Area organizers would be based in Johannesburg.

Chamber of Mines Building (The Heritage Portal)

‘I came here in 1989. My girlfriend was working and living in Johannesburg, I usually visited her on weekends, and I moved in with her. We stayed in a flat in Plein St, corner Wanderers. We finally got married, she’s now my wife. We stayed in the flat until 1993. We had trouble with Inkatha members. My wife was assaulted. There was a break in. We were worried about the baby and we moved out. We found a house in Boksburg close to where Chris Hani was living. Finally in 1994 I bought my own house in Rondebult, Germiston.

‘Regarding my political development, I’d like to mention my visit to England in 1989. A group of us were taken out of the country to get some training in trade unionism. The trip was sponsored by the British Mine-workers Union. As we were driving through London in a bus from Heathrow, I saw for the first time, white people digging trenches in the road. Wow, can this happen?! Because, we thought, this is not the way it is! We stayed at Whitehall College and the people who were doing our beds were white ladies, they were cleaning our rooms and so on. And I remember there was this very nice lady and she would greet us,”Hallo sweetie, hallo love.” Wow, a white lady saying such things to me! Later we visited Trafalgar Square. It was a turning point for me. The Anti Apartheid Movement, they were protesting there, outside South Africa House, twenty four hours a day. And I said to myself, here are people who aren’t directly affected by this, they are white, they are not sleeping, for me to be free. And I still have time to sleep, myself. I started to see real solidarity. It was such a significant part of my political awakening.

South Africa House (via Wikipedia)

‘Also when I was in London, I met Oliver Tambo. I couldn’t stop crying; shaking his hand – he’d had a stroke already, but he was recovering. That was such a pain – here was this person who had devoted so much energy to the cause, he fought his entire life, and now he suffered this stroke. The signs were there already, that we were going to be free soon and I thought, he‘s not going to be able to enjoy what he fought for.

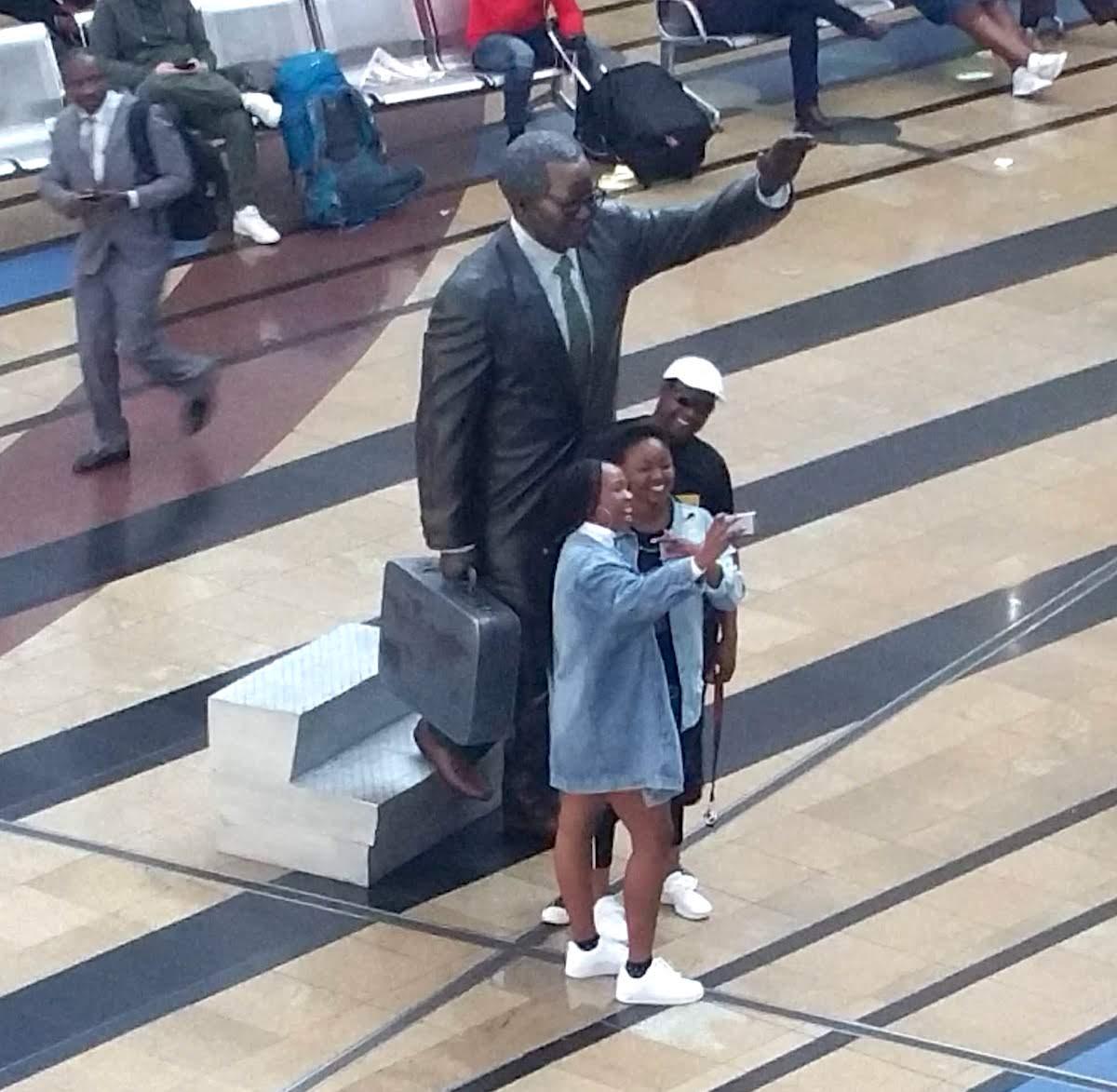

Tambo statue of OR Tambo airport (The Heritage Portal)

‘Another political experience was my participation in Codesa. Now, I was in a committee dealing with ‘leveling the playing fields.’ Sitting on that committee were Professor Kader Asmal, Essop Pahad, just to mention two. Then one just took it for granted, we were just working, but looking back I ask, have I really participated in Codesa, was that me, interacting with those big shots? Pik Botha, Kobie Coetzee of the National Party was there, and reporting at the plenary sessions, there was Chris Hani, Madiba would be there. I interacted closely with Chris Hani, even going to his home to discuss points off the record.

‘The great thing for me was to see Madiba coming out of Victor Verster. It was on TV, we were in a stadium in Welkom. People just flocked there. We had to organize them, address them, provide leadership. It was electric, it was something unbelievable. You sleep and wake up and ask is it real, is it real, is he out of jail? You felt it in your body, ja, ja...

‘Talking about the current challenges in my working life, I must emphasize that trade unionism played a very, very important role in delivering the present. Things have subsequently changed for us. We’re struggling to deal with the present situation and the future. Why do I say this? In the early days it was easy to recruit members into the union. For a progressive union, apartheid was an anchor, a main reason, over and above your bread-and-butter issues. Now that apartheid has gone, we are struggling to convince, especially the new generation, why they should join a union. There are other opportunities open to them now. We educate our members and they leave to become professionals or managers. Or people don’t rush to join. That’s the one part; the other is Globalisation. Trade unions now have to deal with more complicated things. You can’t just go to management, as we did in the past and say, ”We demand A,B,C,D.” We must be able to do research; we must be able to factually motivate what we are tabling. We must recognize where our demands are not practically possible. Issues have become less emotive. The world has changed for trade unions.

‘Another huge challenge is the issue of class consciousness. In the absence of strong class consciousness people might chase material things rather than look at the need for a collective advancement. We seek a betterment in the lives of not only those who are working but those without jobs. We try not to be seen as having narrow interests.

‘The critical challenge for South Africa is to end poverty: to provide jobs, infrastructure, to meet basic needs. There’s too much unemployment. Another challenge is the skills question. As the country develops economically, how do we position ourselves to effectively participate in that development with the necessary skills. That’s why we run our own training college in Yeoville. We develop shop stewards by giving them administrative and leadership skills. We send our people to institutions of higher learning where for instance, they do finance and human resources courses. We’ve even created a few MBAs.

‘Another point that is even more worrying for me is what type of South Africa are we creating? We are starting to see tendencies of greediness, tendencies of individual wealth accumulation. If we’re not careful we’ll have a situation of filthy rich, while the poor remain as they were. The society has stabilized; we have to catch up but must it be a BMW as the first car, must people immediately move into a fancy town house? What sort of society will we become? Will it be based on materialism or where we firm up the basics, where no one lives below a certain reasonable level?

‘I’m not worried about race relations. At primary school level the kids are integrating; there’s no distinction. What does worry me is that our children already are not aware; how do we ensure that our recent history is not forgotten?

‘On a personal note, one of my life’s great moments was the birth of my first child. I was fortunate because I never had scandals of a baby outside of the marriage like some of my friends. Now, I got married and here, I’m going to have a child. It was marvelous. I kept asking, is it going to be a boy, I wanted a boy. I was in the labour ward, it was so exciting and it was a boy. Our bonus second child was a girl so it was perfect.

‘Even at my age I miss my mother. Because she passed on when I was young, I never had the opportunity to be like other kids with their mother so I still have that baggage, the personal pain inside me. One day I want to write a book about the behaviour of men who have children and don’t take responsibility for those children. There are too many kids without fathers. They are likely to find themselves in a permanent poverty chain because their fathers chose not to take responsibility. It’s something about which I’d like to satisfy myself, if I’m still alive, to research, to write, to ask those concerned, how are they feeling that their father’s not around to take care of them? My wife had children when I met her. The men were no longer there. I look after those children today as if they are my own.’

About the author: Mike has spent most of his life in Johannesburg. He earned his living as a human resources practitioner, first in large companies as a manager, [many stimulating years with AECI] and later in his own small HR consultancy. Much of his later occupational time was spent running training courses for managers on how to handle staff within the framework of South African labour legislation, He wrote and published The Manpower Brief, an IR, HR and sociopolitical newsletter, which was popular in many large companies during the 80s and early 90s. A selection of Briefs were incorporated into the book, People Really Matter published by Knowledge Resources. While working, he wrote several business books, one of which, on negotiating, was a sell-out.

In his ‘retirement,’ he has written extensively about Johannesburg, publishing articles mainly in The Star and Sunday Times. Working with Beryl Porter of Walk & Talk Tours, he developed and guided many walking tours around historic Joburg – Braamfontein, Parktown, Newtown, Centre City, Constitution Hill, Kensington & Troyeville, Fordsburg etc. He regularly took visitors to Soweto. His book Johannesburg Portraits – from Lionel Phillips to Sibongile Khumalo, offered popular biographical essays of well known Joburg citizens. His researched paper on Judge FET Krause who surrendered Johannesburg to Field Marshall Roberts during the Anglo-Boer War, was published in the Johannesburg Heritage Journal. The same journal published his series on famous local paleoanthropologists.

Mike is also a widely published poet. Botsotso recently published his third book of poetry, Poetic Licence. His current historical work, published by co-author Peter Delmar of the Parkview Press, The Johannesburg Explorer Book, takes readers on a journey through old Johannesburg, weaving together a history of events and people, which make this city such a fascinating place. His most recent book, a work of journalism, Twelve plus One, featuring transcribed interviews with Johannesburg poets was issued in 2014.

He lived with his wife Cecily, in a century old, renovated house on Langermann Kop, Kensington. A widower since July 2014, he now lives in Eventide Retirement Village in Muizenberg. He believes himself very fortunate in that his son, daughter in law and grandsons live nearby. His daughter lives in Sydney with her husband and son. In case you’re wondering, Luke Alfred, Mike’s son, is the well-known journalist and author.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.