Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

A recent invitation to spend a weekend in the Western Free State provided an opportunity to visit the cemetery at the small town of Bultfontein. Situated approximately 90 kilometres north of Bloemfontein, I had passed through this town at least fifteen years ago, when I cursorily traipsed the cemetery. This time I undertook to explore it in more detail.

Although approval for the establishment for a village was granted in 1862, disagreement as to the site delayed the laying out of the town until 1873, when it was decided to lay out two towns, one at Bultfontein and one at Hoopstad. The former was established on the farm Bultfontein and accordingly named in 1874. Reputedly, it has the largest grain silo in Africa and quite possibly in the southern hemisphere, with a capacity of 850 000 bags.

The cemetery, opposite the town’s handsome Dutch Reformed Church, seemed to be reasonably maintained with little evidence of vandalism visible. This Church was designed by Hendrik Vermooten (1921-2013), a prolific church architect who had apparently designed 144 churches across South Africa. Vermooten adhered to a distinctive style of church architecture, of which the above church seems to be a typical example.

The oldest graves date from the earlier years of the twentieth century and there are several examples of slate tombstones that have survived the intervening years, surprisingly well. Tombstones engraved from slate seemed to have been popular amongst the Afrikaner rural communities, many of these containing unusual and varied symbols adapted from folk art. This may be because slate is relatively inexpensive, hard wearing and relatively easy to shape and engrave.

Typically, the slate tombstones are arched at the top, symbolising the celestial heavens. Generally, such tombstones are rectangularly shaped, but occasionally, more curved profiles were adopted.

Images signifying death and the Christian concept of rebirth or afterlife are commonly engraved on the tombstones. Such images generally reflect the rising sun, the flying dove holding a stem in its beak, the tree of life, or a flower often withered, all of them representing death and rebirth. The handshake indicating the parting from earthly life or hailing the afterlife, is another common image.

Slate tombstone of Gesina Pienaar (1872-1925) displaying a plant signifying rebirth following death (SJ de Klerk)

Slate tombstone of Abel Jacobus Pienaar (1867-1935) displaying the rising sun, signifying daybreak after the dark or somber night and life after death (SJ de Klerk)

The Pienaars must have been prominent in the area as there are quite a few tombstones of this family.

Unusual but beautifully engraved slate tombstone of Elizabeth Fosina Maria Strating 1847-1887 (nee Van Buuren) (SJ de Klerk)

Intricate slate tombstone of Johannes Hermanes Fourie (1877-1935) containing images of plants, the dove and tassel of the cloth traditionally covering the deceased (SJ de Klerk)

For the South African War enthusiast, there are six tombstones of deceased Imperial soldiers to view. Rather surprisingly, Jackie Grobler omits any mention of these and the adjacent two Boer burgher graves, in his otherwise informative guide to memorials and sites on the South African War. Unfortunately, or perhaps fortunately for their continued preservation, three of the graves were enclosed by a steel fence, where weeds somewhat impeded deciphering of the epitaphs. One reads: ‘Private Thomas Mooney. Thorneycroft Mounted Infantry. Killed at Hartenbosch 8 April 1902.’ One can only assume that all three interred within the enclosed section were killed in the same skirmish.

The grave of Captain Percival Coode, DSO, of the West Riding Regiment, the sixth and youngest son of a prominent family from Polapit Tamar, Launceston, is covered by an attractive Celtic cross.

Celtic cross tombstone of Captain Coode DSO (SJ de Klerk)

Captain Coode was killed with Colonel Ternan’s column at Hartenbosch near Bultfontein on 8 April 1902. The Times History of the War in South Africa dismisses this skirmish rather scornfully: ‘…. when Ternan dispatched a party of 200 men from Bultfontein to clear some farms at Hartenbosch. The whole force, after a feeble resistance was captured by Badenhorst.’

This seems somewhat unfair to Goode and the two others killed in action there. The resolve of the Imperial troops may have been weakened by the imminent peace talks. Nobody wishes to die needlessly during the last days of a war.

Goode had served during operations in Rhodesia, 1896, where he was wounded. Because of his South African experience, he was specially sent from Burma to the Cape in the early days of the South African War and saw much service on the Staff and with Mounted Infantry. He was present at actions as diverse as Poplar Grove, Driefontein, Diamond Hill and Bothaville. Mentioned in the despatches by Field Marshall Roberts, he was also awarded the DSO.

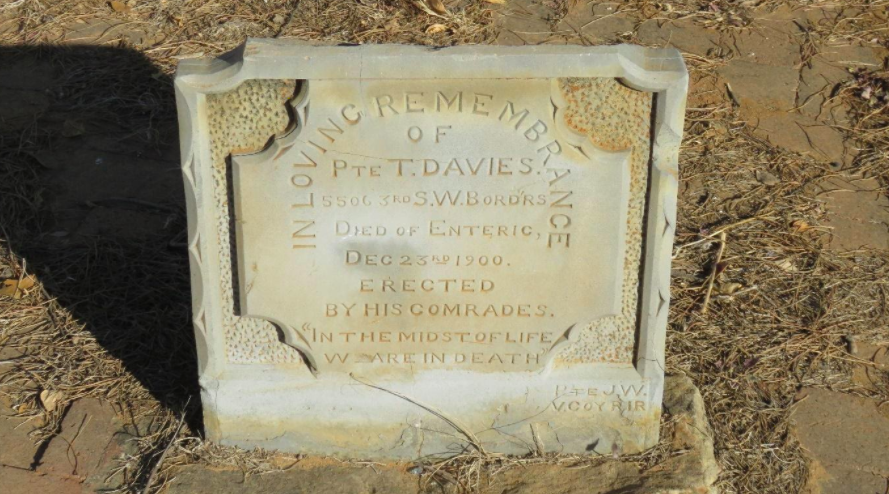

Adjacent to their graves is an engraved slate tombstone for Private T. Davies of the South Wales Borderers, previously the 24th Regiment of Foot. Davies had died of enteric, perhaps the biggest killer of Imperial soldiers during this war. Unusually, the name, or rather the initials of the engraver is also inscribed; Private J. VV. of V Company, Royal Irish Regiment.

Tombstone of Private T. Davies (SJ de Klerk)

Today, enteric is known as typhoid and is caused by the bacterium Salmonella typhi (S. typhi). The bacteria spreads through contaminated food, drink, or water. People infected with Salmonella typhi carry the bacteria in their intestinal tract and blood.

The tombstone of Lieutenant Arthur Henry Thomas of the Ceylon Mounted Infantry states he was killed in action at Hammonesfontein on 4 October 1900.

Partly covered tombstone of Lieutenant Arthur Henry Thomas of the Ceylon Mounted Infantry (SJ de Klerk)

Confusingly, Thomas’ tombstone states he was killed in action, while; ‘The Last Post being a roll of all Officers who gave their lives in the SA War’, says he died from enteric. I could find no mention in the Times History of Hammonesfontein and it was probably one of hundreds of unrecorded small clashes during this war.

Near the Imperial graves are two graves of Boer burghers also killed in this conflict. One is of Burgher Daniel Johannes Bloem who died from his wounds on 7 December 1901.

Family grave site of Daniel Johannes Bloem and his wife Frederika Isabella Bloem (nee Havenga) (SJ de Klerk)

Note his original hand carved slate tombstone in front of the later erected one.

The other burgher grave is that of Jan David Ungerer, wounded on 1 June 1901 at the ‘Soutpan’ (Saltpan) and died four days later at Bultfontein. Soutpan must be the town of the same name situated some 47 kilometres south of Bultfontein.

Tombstone of Burgher Jan David Ungerer. Note the remains of two earlier tombstones placed in front (SJ de Klerk)

The last two tombstones relate to two other important events in our history, namely the 1914 Afrikaner Rebellion and the 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic. The first grave is of Jacobus Johannes Zwart, a rebel, wounded on Monday 16 and died on Saturday 21 November 1914, during the Afrikaner Rebellion.

Tombstone of J. J. Zwart who died of his wounds during the 1914 Afrikaner Rebellion (SJ de Klerk)

It would seem Zwart was seriously wounded during a skirmish on 16 November 1914, when government troops commanded by Colonel J. G. Cilliers clashed with a large group of rebels spread across the farms of Verhelsleegte and Doornpan, some 18 kilometers west of Bultfontein.

Cilliers with a force of 1 000 men from the Potchefstroom Commando stationed at Boshof, received orders to prevent this rebel force of about 1500 men that were active between Hoopstad and Bultfontein, from entering the Boshof district. At about 06h00 the government troops attacked and after a short but intensive fight, the rebels retreated in small groups towards the north-east and due to their mounts being in superior condition, mostly managed to escape. About 100 rebels were captured together with large quantities of rifles, ammunition, horses and wagons. Apparently four unidentified rebels were killed. A further twenty rebels were wounded, while the government troops suffered six wounded.

For some time now I have been on the lookout for graves from the 1914 Rebellion when visiting outlying cemeteries. Some of these graves have been located in cemeteries at Senekal, Winburg, Kingswood Station, Vrede, Reitz, Harrismith and now also Bultfontein. Hopefully these and other still to be located graves, will form the basis for a future article on this very interesting rebellion.

Joint tombstone of husband Jacobus Frederik Olivier and wife Dirkina Jacoba Olivier, both succumbing to the Spanish Flu on 1 November 1918. The epitaph reads: ‘Beide overleden 1 Nov 1918 aan de Griep’ (SJ de Klerk)

Unfortunately, the combination of early morning sun and broken horizontal tombstone prevented taking a clearer photo.

The magisterial district of Hoopstad, which included Bultfontein, was fortunate to largely escape the ravages of this pandemic. This district only experienced 6.76 deaths per thousand people, the second lowest after Vredefort/Parys in the Free State Province. Still it must have been a severe blow to the Olivier family to lose the husband aged 38 years and spouse aged 39 years, to the dreaded Spanish Flu.

According to Howard Phillips people in the age-group 15-45 were particularly susceptible to the Spanish Flu.

About the author: SJ De Klerk held many senior positions in HR during a distinguished career in the private sector. Since retiring he has dedicated time and resources to researching, exploring and writing about South African history.

Bibliography

- Bothma L. J. 2017. Rebelspoor: Die aanloop, verloop en afloop van die Boereopstand van 1914-15. Published by LJ Bothma, Langenhovenpark.

- Dooner M. G. 1980 Reprint. ‘The Last Post’: Being a roll of all Officers who gave their lives for their Queen, King and Country in the South African War 1899-1902. J. B. Hayward & Son, Suffolk.

- Phillips H. 1990. ‘Black October’: the Impact of the Spanish Influenza Epidemic of 1918 on South Africa, in Archives Year Book Fifty-third Year – Vol. 1. The Government Printer, Pretoria.

- Erskine Childers (Editor). 1907. The Times History of the War in South Africa 1899-1902. Vol V. Sampson Low, Marston & Company, Ltd. London.

- Grobler J. 2018. Anglo Boer War: Historical Guide to Memorials and Sites in South Africa. 30° South Publishers, Pinetown.

- Watt S. 2000. In Memoriam: Roll of Honour Imperial Forces – Anglo Boer War 1899-1902. University of Natal Press, Pietermaritzburg.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.