Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In 1985 I found a brown A4 paper envelope at the Triomf municipal rubbish dump. The Triomf dump was a popular place for students to look for old furniture and household items, faded Tretchikoff prints, magazines and books. The dump no longer exists. The A4 brown paper envelope, which had a date, 1979, written on it in pencil, was found on the top of other rubbish in a large skip so must have been newly thrown away. It seemed likely that ‘Dad’ had passed away circa 1979, and that his family had kept some of his things, finally throwing them out in 1985. This small archive has intrigued me ever since. The archive attests to how some items are 'time travellers' and are kept, while other items are thrown away - and then found again. From these scant artefacts I have attempted to determine what Mr Man Tong’s life in Richmond might have been like.

The material in the brown envelope consists of the business records of a Mr Man Tong from Canton (Guandong province) in China who ran a grocery shop at 25 Stanley Avenue, Richmond, in the 1940s until 1953. His real name was Li Guang He, as this is how he is addressed in the six letters received from a family member in Foshan in China. Man Tong was a generic nickname for a Chinese man, yet Li Guang adopted it as his ‘trade name’ for both his business and various local relationships. Presumably Mr Man Ton also came from Foshan. Foshan is a very large, prefecture-level city in central Guangdong Province, China

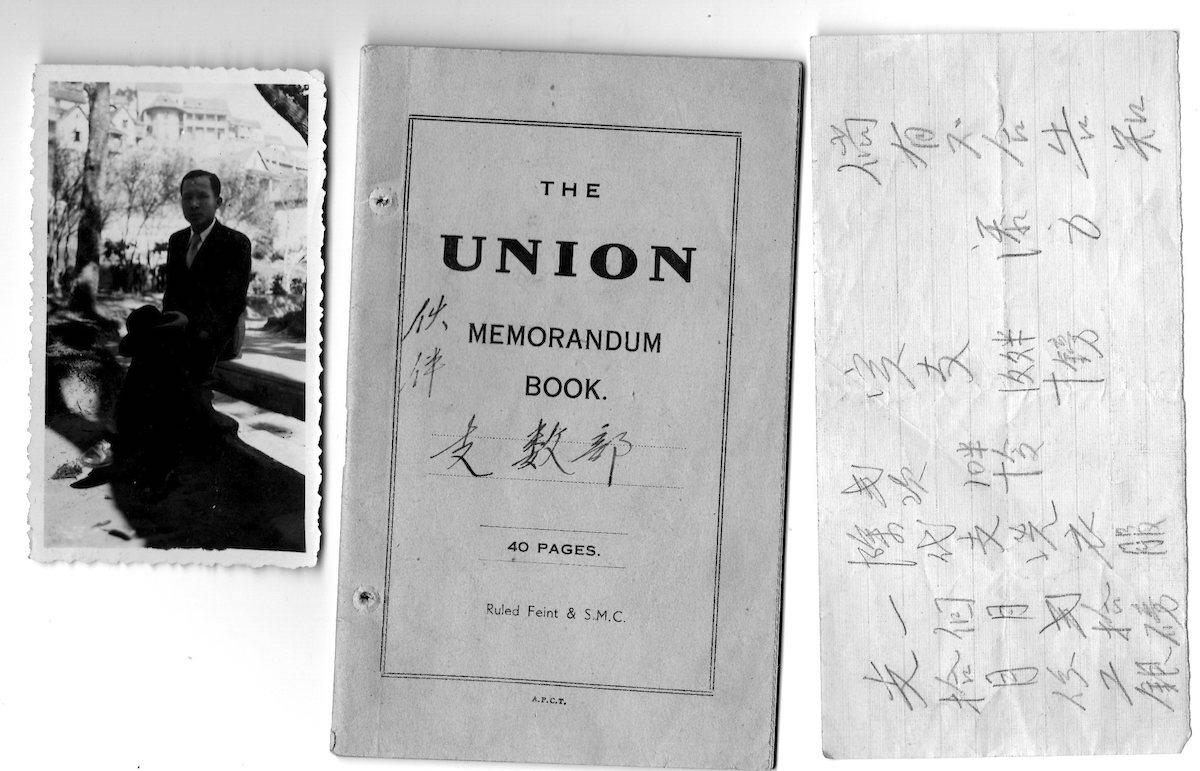

The envelope contains a photograph of a young Chinese man, probably of He Rhu Zhu, Mr Man Tong’s younger brother, who wrote many letters to Mr Man Tong around 1948. There was also a pair of round metal frame spectacles which may have belonged to Mr Man Tong.

Some of the items in the envelope, including a photograph He Rhu Zhu, Mr Man Tong’s younger brother, who wrote many letters to Mr Man Tong around 1948.

As I cannot read Chinese, I could not do much with my find, but a chance contact at the University of Witwatersrand revealed a path whereby the letters and other material might be translated researched to shed light on Mr Man Tong, revealing a small life in the suburb of Richmond in the Johannesburg of the 1940s and 1950s. I investigated some of the information in the documents in the envelope and had discussions with Prof Philip Harrison, SAACHI Chair in Architecture and Town Planning at Wits University. Prof Harrison’s colleague, Dr Yan Yang, translated the letters for me, for which I am extremely grateful.

School of Architecture and Planning (The Heritage Portal)

Sadly, this world is now all gone, demolished to make way for university campus, roads, blocks of flats and office developments. Finally, in January 2008, the Richmond Laundries in Napier Street, a formal heritage site, was illegally demolished, removing the last link to the Chinese migrant and merchant presence in those long ago days. So far, it has not been possible to locate photographs of the Chinese community or the shops on the corner of Stanley Avenue and in Stanley Avenue, Richmond, and Barry Hertzog Avenue, noting that specialists doing Heritage Assessments for Development have not been able to do so either (Le Roux and Muindisi, 2016).

Rand Steam Laundries site before demolition (Johannesburg Heritage Foundation)

Rand Steam Development (JICP)

Chinese migrants in Johannesburg

South Africa has the only African multigenerational resident population of Chinese, as well as a growing population of new Chinese migrants (Park and Chen, 2009). Colonial and apartheid governments did not welcome Chinese migrants and they were treated with fear and loathing, and during the 19th and 20th centuries. Their numbers in South Africa did not increase much and by 1953, all migration from China was suspended by apartheid legislation. The National party came into power in 1948 and began a process of promulgating discriminatory legislation. This situation was only released in the 1980s to allow Taiwanese business immigration, and later for immigration from Chinese from Hong Kong and then from other provinces.

Park and Chen (2009) mention that the numbers of Chinese migrants was small in South Africa because of racist legislation (Park and Chen, 2009: 3), and although the numbers of Chinese from mainland China were tiny, they were feared and heavily discriminated against. There was a small increase in new Chinese immigrants during 1949 and 1953 when Chinese brides were brought into South Africa (Park and Chen, 2009), but after that, the Immigrants Regulation Amendment Act (No. 43 of 1953) closed the door for Chinese migrants to enter South Africa.

The early Chinese families who set up shop and restaurants in Johannesburg’s Commissioner Street China Town, have now almost all moved away, having educated their sons and daughters to be doctors and lawyers and no longer shopkeepers. A newer group of post-apartheid era Chinese migrants have set up small shops in Derrick Street, Cyrildene, and run grocery stores and restaurants, or have kiosks in the City Centre or in the various ‘China Malls’ and hardly speak any English, and are subjected to considerable xenophobic sentiments. Many other Chinese migrants in South Africa are currently of illegal status, and are from peasant stock and occupy a low social level in South Africa’s many small towns. They also hardly speak any English (Park and Chen, 2009).

The famous Swallows Inn Commissioner Street (The Heritage Portal)

Derrick Street Entrance (Mark Straw)

A PhD study by YJ Park (2006) notes that, over the course of three generations, Chinese immigrants to South Africa gradually moved from their ‘humble origin’ as uneducated immigrants working as corner grocers to become a relatively highly educated, largely professional, solidly middle class South Africans considered as equals (Chapter Four: Shifting Chinese South African identities in Apartheid and Post-Apartheid South Africa by Park, Yoon Jung).

This study notes that in South Africa, apartheid laws clearly defined the Chinese as ‘non-white’ but the Chinese increasingly became ‘honorary whites’. Throughout their lives, they received conflicting and changing social messages about where they fitted in South African society. This is likely to be what Mr Man Tong also experienced, and he, seemingly not uneducated, definitely owned (not merely worked in) a ‘corner grocery’ store.

Mr Man Tong’s grocery business

In the archive, there are also 18 cheque books with stubs, and bank statements with attached ‘paid’ cheques relating to Mr Man Tong’s grocery business which he operated from 25 Stanley Avenue. There are also many notebooks where he kept inventories of his stock, written in English in pencil, as well as invoices from suppliers (for example, from Ely Lilly household cleaning agents). Mr Man Tong’s shop stocked soaps, washing powders, floor polish, household soaps and the like, and not fresh produce or food items.

Li Guang He, or his adopted name, Mr Man Tong, seems to have run his business very efficiently and successfully and from the admittedly scant evidence, and did not run into debt, was not besieged by lawyers letters requesting payment for goods or services, and all his cheque payments were for legitimate business expenses and transactions. He seemed to be very well-versed in English as he ran his business in English.

We can assume that Mr Man Tong arrived from China and was not born in South Africa as he had strong links with a brother back in China. It appears from letters that Mr Man Tong’s brother, Hu Rhu Zhu, also travelled many times between China and South Africa and ran his own small shop in Mayfair. However, Mr Man Tong was literate in English and conducted all his business transactions at the shop, and his interactions with the Johannesburg Municipality (traffic fines) in English. All his documents were written in English, either in ink pen or pencil in good copperplate style.

Even in the 21st century, one of the key issues for incoming Chinese immigrants was their lack of English language skill, which creates difficulties in running their businesses, employing local staff and exacerbates their social isolation (Park and Chen, 2009:13). This would have been the same situation in the 1940s and 1950s, and we assume that this was not a problem that Mr Man Tong experienced as he did his business correspondence in good English.

In this small archive, there are no documents pertaining to property ownerships, rental or a lease, so we don’t know who actually owned the shop. None of the cheques are written to any person who could potentially be a landlord, and there are no title deeds or anything relating to the building itself. Perhaps Mr Man Tong paid his rent in cash, or actually owned the shop. There are also no cheques for rates, taxes, electricity or water.

There are licence documents relating to vehicles and at various times he owned small trucks, and received parking fines for them (which were all paid up).

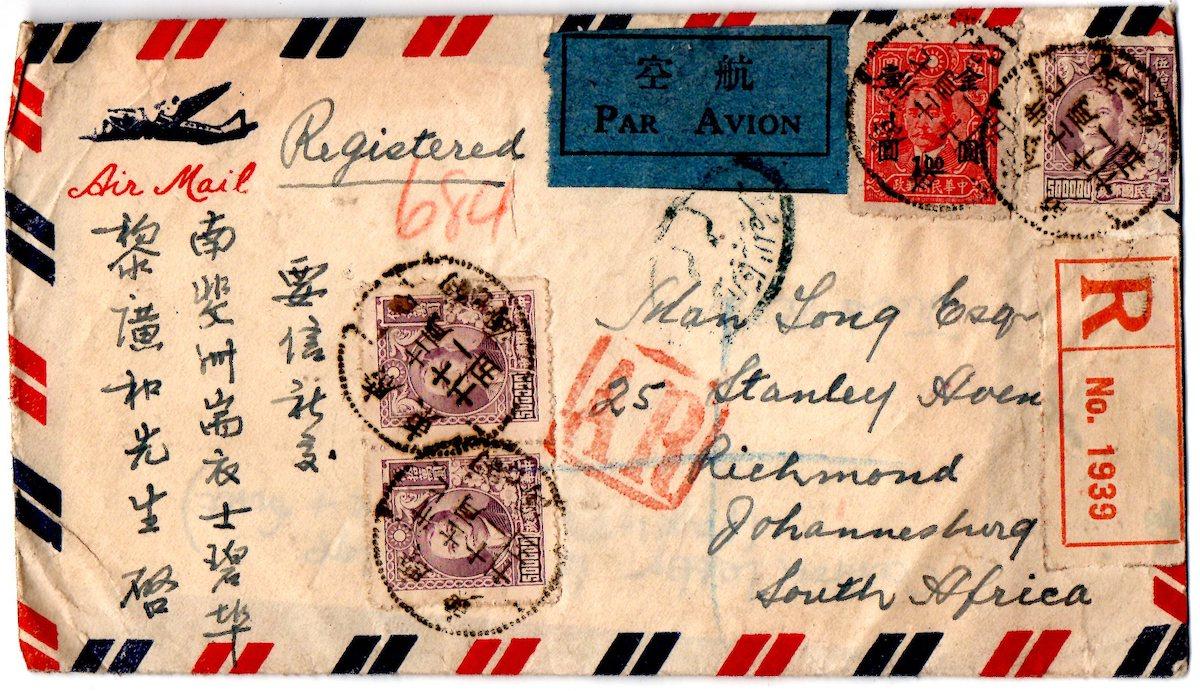

The six airmail letters (see main image) originate from China, from a younger brother, He Rhu Zhu, with ‘brother’ perhaps just meaning a term of familiarity, and not necessarily a blood brother. They are addressed to Mr Man Tong, Esq, 25 Stanley Avenue, Richmond, Johannesburg, and are dated 17, 24 and 30 May, 15 August 1948 and two letters are dated December 9th 1948. There is another letter from He Rhu Zhu, dated 27 March 1949. The letters are written in Chinese (Cantonese). Many Chinese migrants to South Africa in the early 20th century were from Fushan in the south of China. The letters to Mr Man Tong were found to contain only small family chat, and nothing relating, for instance, to political or economic conditions in China at the time and which would have been of academic interest.

He Rhu Zhu does mention that within China there was a lot of economic uncertainty and peoples’ lives are hard but in their ‘hometown’ it is still peaceful. The security situation in Foshan is a little better, says He Rhu Zhu, but there is no beneficial situation anywhere. “We are glad to say that those of us, including me, who came back into this difficult situation are still safe”, he writes.The letters from Ze Rhu Zhu also ask Li Guang He (Mr Man Tong) to help him with loans, to check on his own shop in Mayfair, Johannesburg, or to help other family members who were travelling by boat to South Africa, or to send more medicinal soap. He Rhu ZHu apparently suffered severely from eczema and apparently the Cuticura soap was the only thing that really helped.

These six letters were probably part of many hundreds of letters from He Rhu Zhu over the years, given that He Rhu Zhu seemed to be a prolific and demanding letter writer (three letters in May 1948). Why these six letters from He Rhu Zhu were saved, and not others, we will never know.

Records of Mr Man Tong’s grocery shop and business

The address for the original business material and letters is always 25 Stanley Avenue, Richmond Johannesburg so this is where Mr Man Tong’s grocery shop flourished for so many years, from about 1942 to 1958 when the last cheques were written and paid by the bank. Mr Man Tong probably lived in quarters behind the shop as this was style then. Richmond is a suburb of Johannesburg, and is close to Auckland Park, Braamfontein Werf, Cottesloe, Jan Hofmeyr, Melville, Rossmore, Westdene, Hurst hill, Brixton, Crosby, Coronationville, Westbury and Newclare. and is also reasonably close to the Johannesburg city centre. It was also near to the mixed race area, Sophiatown, which was demolished in the 1950s and rebuilt as a whites-only suburb named Triomf. These suburbs were all working class suburbs, established around the previous turn of the century: Auckland Park (as early as 1888), Vrededorp, Richmond and Melville (1896), Parktown West and Brixton (1902) and nearby Cottesloe (1904).

Cottesloe Church and Joburg Skyline (The Heritage Portal)

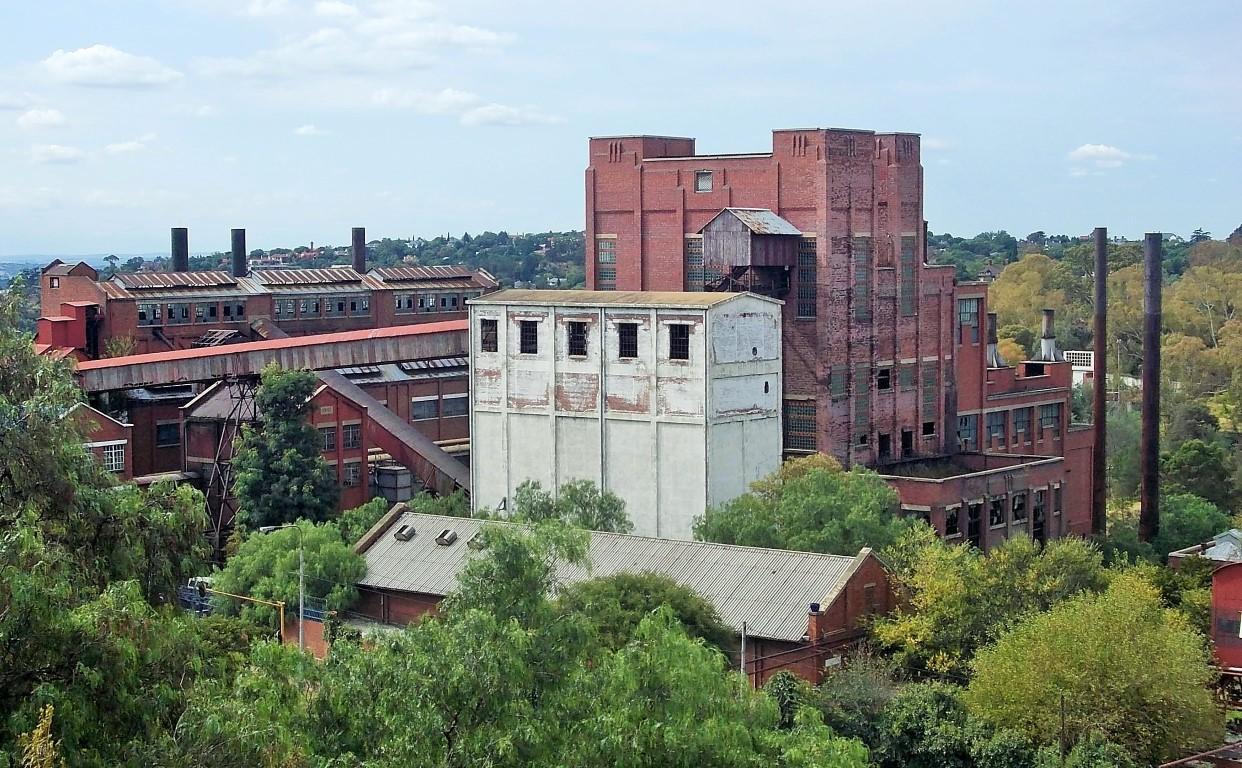

Mr Man Tong’s shop was also very close to the Rand Steam Laundries, Cleaning and Dyeing works located on the corner of Barry Hertzog Avenue and Napier Street in Richmond, and which operated from 1902 until 1963. People working at the laundry might have visited his shop. The original laundry buildings were some of the oldest industrial structures in Johannesburg and had protected heritage status. The entire Rand Steam complex was illegally demolished in 2008 and this demolition removed one of the last traces of history of the early 20th Century Chinese immigrant class in Johannesburg. The Rand Steam land and some of the remaining infrastructure has now been developed as an upmarket retail and restaurant centre, called Rand Steam.

The Blue Plaque at the new Rand Steam Laundries site (Lucille Davie)

Investigating this community and other small enclaves of Chinese influence in the western areas of Johannesburg, it seems that this community was very small and that history does not record who any of these Chinese persons were, and what their businesses were about. There do not appear to be any early street level photographs of 25 Stanley Avenue and any of the various other shops and houses which must have been situated on that section of Stanley Avenue.

Reading a 2014 Heritage Assessment by PGS Heritage for the redevelopment of the Rand Steam site, even the heritage assessors could not find any photographs in existence taken in this general area. Going through another 2016 Heritage Assessment for the Heritage Impact Assessment and Conservation Management Plan for the Empire-Perth Development Corridor, prepared for the City of Johannesburg’s Johannesburg Development Agency (JDA) (JDA, 2016), there is no mention at all of a former Chinese community in this area, and oddly, also no mention of the Rand Steam Laundries even though the demolition of these laundries in 2003 would have been a fairly recent issue. Even an archival and historical study of the Rand Steam Laundries by Impendulo Design Architects in 2014 does not mention a Chinese connection.

Email discussions with the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation revealed that they have no archival photographs of any early Richmond or of any Chinese shops in Stanley Avenue. A 2009 academic paper titled ‘Ruins of the past: industrial heritage in Johannesburg’ by Läuferts and Mavunganidze of the University of Pretoria’s Department of Construction Economics also does not make any mention of Chinese residents or shopkeepers in the general Stanley Avenue and Gas Works area of Richmond, Johannesburg. As all these studies consistently do not mention any Chinese shops or houses that might have existed in area in the past and it could be said, that the Chinese presence in this area has been erased.

The Old Gas Works (The Heritage Portal)

This lack of mention could mean that without the Mr Man Tong archive, this era and tiny history of Johannesburg would have gone unrecorded, except perhaps by Mr Man Tong’s descendants. Clearly more archival research is needed – along with a few more lucky breaks, and a trip to the Images Collection at Museum Africa.

The difficulties in tracking down Mr Man Tong’s shop

Using Google Earth, there is a piece of derelict land visible at the corner where Empire Road crosses Barry Hertzog Avenue, and becomes Stanley Avenue. Stanley Avenue is now bisected by Barry Hertog Avenue. The 25 Stanley Avenue-Barry Hertzog Avenue corner has been a derelict site for many years, and may be the former location of the shop. Using Google Earth (2018 images), the site has now been cleared of vegetation (which is visible in 2001 Google Earth images) and looks like it is now being developed. Also, in this segment of Stanley Avenue where the shop may have stood, there is a large block of flats in a 1980s unmemorable modern style. Presumably this is also where other similar Chinese retail establishments may have stood. Finding old photographs of Stanley Avenue would help to clarify the exact location of the shop and its milieu.

The derelict piece of land (Google Maps)

I have not yet been able to find when the shop at 25 Stanley Avenue was demolished. There does not seem to have been any ‘heritage’ debate at the time, at least not showing up on the Internet. There also does not appear to be any online press reporting of the destruction of Stanley Avenue’s original shops, houses, factories and businesses although these buildings may have lingered into the 1970s. Their destruction was part of changes to the area that saw 44 Stanley Avenue and the small industrial area next to the Johannesburg gas works being ‘rescued’ and repurposed into an upmarket office, shopping and restaurant precinct. The shop and other buildings may have been in very bad condition by then, and also were not old enough to be considered as ‘heritage’. The Johannesburg main library and its newspaper archives will be consulted to see if anything was mentioned in the press at around this time.

I have walked around where 25 Stanley Avenue stood many times, as I keep hoping I will be able to imagine the small street with its row of shabby Chinese shops, bustling with activity, animated with purpose in an otherwise hostile city. I still hope to find some of the discards from the actual shop as it was demolished, perhaps a piece of painted plaster with the remnant of a Chinese symbol, very faintly remaining. It would have been electrifying to find something tangible of that long forgotten world that Mr Man Tong would have touched or seen every day. I remind myself that I have Mr Man Tong’s notebooks and his bank cheques, all written by his own hand in perfect English.

So, he was an educated man, perhaps from a well-to-do Cantonese family. It could not have been every Chinese migrant to Johannesburg at that time who could afford to get on a boat and come to South Africa, and then set up a shop and then do so well. Mr Man Tong’s contemporaries would have been the Chinese shop owners in Diagonal Street, at the west end of Commissioner Street and Chinese shop owners in Mayfair, Johannesburg. In fact, in Mr Man Tong’s letters from his brother, He Rhu Zhu mentions his own shop in Mayfair and that he was taught English by Mr. Goodel who lived at 7B, 19th Street, Vrededorp.

Strange semi-derelict building on the corner of Stanley and Barry Hertzog Avenue

The building above, which appears rather old, covered in graffiti, and functions as a spaza shop. There is always a gathering of people outside this shop, which is why I have been hesitant to prowl around and take photographs. It is about 50 metres from where Mr Man Tong’s shop would have stood (and which is where the brown face-brick building is located in the above photograph).

I aim to find out more about the history of this small place as it may be be the last surviving remnant of mid-1940s ‘poor people’s’ buildings in Richmond, and a contemporary of Mr Man Tong’s shop. Mostly, the buildings that have survived in Richmond and surrounds are schools, churches and other formal institutions, all for ‘wealthy white people’ and the dominant classes. The buildings of the poor are not usually noted as of architectural value, yet the lives of the poor, including the lives of Chinese migrants, are extraordinarily interesting. The study of migrant lives and Diasporas is now a very large endeavour around the world.

About the author: Sue Taylor is a development consultant with experience in researching, writing and lecturing about climate change and social/development issues in South Africa and Africa. She has worked in the NGO sector as a climate change activist, and then in the consulting and academic sector as an independent researcher and science writer. Her current interest is in cities and migrants in Africa. She is also writing for the Africa-China Project at Wits University. She has a biotechnology and agriculture blog at https://botanybiznews.co.za

References

- Park YJ (2009). Chinese Migration in Africa. South African Institute for International Affairs Occasional Paper no. 24. China in Africa Project.

- Park YJ & AY Chen, ‘Intersections of race, class and power: Chinese in post-apartheid Free State’, unpublished paper presented at the South African Sociological Association Congress, Stellenbosch, July 2008

- Le Roux M.L and Muindisi J (2016) Empire-Perth Development Corridor. Knowledge Precinct, Heritage Impact Assessment and Conservation Management Plan, Report Phase 3. Tsica heritage consultants. tsica.culturalheritage@gmail.com

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.