Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

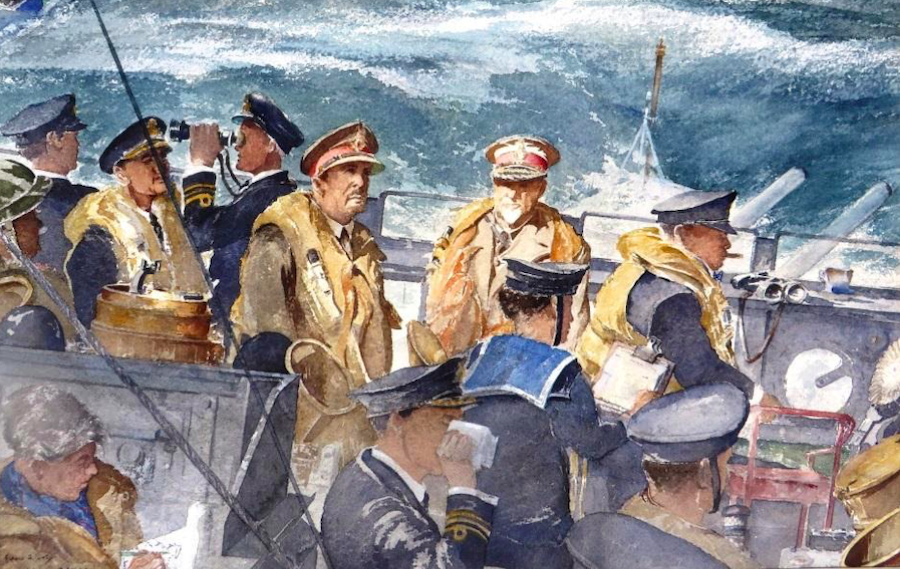

The military art collection of the Ditsong National Museum of Military History includes a watercolour entitled, “HMS Kelvin – D-Day +6” by Francis Flint. The painting is noteworthy in that it portrays three important personalities of the Second World War (1939 – 1945) – Sir Winston Churchill (Prime Minister of the United Kingdom); Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke (Chief of the Imperial General Staff) and Field Marshal Jan Christiaan Smuts (Prime Minster of the Union of South Africa). The event was the visit by Churchill to Normandy on 12 June 1944, six days after the initial invasion took place on 6 June.

One can understand Churchill and Brooke embarking on such a visit but why would Smuts, the Prime Minister of a small Dominion within the British Commonwealth of Nations, be travelling with them across the English Channel? After all there was no official South African participation in the Allied landings in Normandy.

At the time South Africa’s contribution to the war was relatively moderate in comparison to that of the major powers and other nations on the Allied side. Despite that Smuts had developed a substantial international reputation since he had first been appointed to the Imperial War Cabinet during the First World War (1914 – 1918) and played a leading role Treaty of Versailles and the formation of the League of Nations at the end of that war.

Smuts and Churchill’s first interaction was during the Anglo-Boer/ South African War (1899 – 1902) when the latter, then a war correspondent in the British Army, was captured by the Boers and held as a prisoner-of-war in Pretoria where Smuts interrogated him. At the conclusion of the war, and after Churchill had been appointed Under Secretary of State for the Colonies in the British Government, the two men successfully negotiated responsible self-government for the former Boer Republics.

This collaboration formed the basis of a friendship between the two that would last for almost half a century. As this relationship was fostered, Smuts developed a deep influence on Churchill, a man who wielded a powerful personality with unbounded confidence and faith in his own destiny. Churchill would eventually regard Smuts not only as an equal, but in many ways superior to himself.

Following the outbreak of the war in 1939, Churchill often sought Smuts’ council at critical periods. A well-documented stream of lengthy two-way messages provides details of the interaction between them throughout the war. Churchill himself recorded how his confidant would fortify his conclusions by the “... massive judgement of Smuts”. Smuts travelled to the United Kingdom on four separate occasions over this period to meet with Churchill and it was during his third visit in 1944 that the events depicted in the painting unfolded.

Smuts arrived in London on 21 April 1944 to attend the Commonwealth Prime Ministers’ Conference. At the time secret preparations for Operation Overlord, the Allied landings in Normandy, were about to reach a climax. At the conclusion of the conference, Churchill invited Smuts to remain in the United Kingdom for the period of the invasion. The invitation proved fortuitous as the South African was to play a central role as Churchill’s personal advisor and apply all his political skill to keep the British Prime Minister in line of not only with the wishes and objectives of those tasked with executing the operation but also of those of King George VI.

Churchill had initially opposed the cross-channel operation and lamented the deferral of his own Mediterranean strategy. The Allied Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee requested that Smuts use his considerable expertise to win Churchill over to backing the operation. Once he had achieved this, a further challenge was to curb Churchill’s persistent meddling in just about everything to do with the invasion plans. The Prime Minister demanded that he personally lead the troops across the Channel and be ashore with the assaulting forces. It eventually took an intervention from the King to insist that Churchill was too valuable to be risking his life on such a fool’s errant.

Churchill would eventually get his wish to go to Normandy once the initial landings had proved successful and on 12 June he boarded the Royal Navy K-Class destroyer, HMS Kelvin, accompanied of course by Smuts and by Brooke. The painting by Flint vividly illustrates the three of them en route across the Channel. Brooke recorded in his diary that they passed convoys of landing craft, minesweepers, parts of floating breakwater and piers etc being towed out. They came in sight of the coast at Courseulles-sur-Mer at around 11:00. Everywhere they could see ships of all sizes and shapes and, after passing a row of LSTs (Landing Ship Tanks), they finally arrived at a Gooseberry which was a row of ships sunk in a half crescent to form a some sort of harbour.

Brooke, Churchill and Smuts on their way to Normandy (via World War II Today)

They were then transferred onto a D U K W (a six wheeled amphibious vehicle) which took them onto the beach to be met by Gen Sir Bernard Montgomery, the GOC 21st Army Group tasked with the invasion. Thereafter they made their way by jeep to Montgomery’s headquarters near Bayeux. An incident, referenced in various sources, occurred later on that afternoon. While standing outside Montgomery’s HQ, Smuts apparently sniffed the air and stated that he could smell Germans in the vicinity. Two days later two fully armed German paratroopers emerged from a nearby Rhododendron bush where they had been hiding after being separated from their unit. Had they chosen to fire on Churchill and his party the course of the war might have been changed.

On completion of the visit, the three were taken back to the destroyer to begin their voyage home. At the time several ships were bombarding a German position and, according to Brooke, Churchill was keen to take a shot at the Germans himself. The Kelvin let off a few rounds which apparently had little or no effect on the German defences. Thereafter they commenced the journey back to the United Kingdom and arrived back in London shortly after 01:00.

The painting in question can therefore be considered descriptive evidence on just how close Smuts was to Churchill and how indispensable he had become to the war effort. It was even proposed, but not formally approved, that Smuts should replace Churchill as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom if he were to die in office prior to the war being concluded. In any event it is well documented that Smuts never left Churchill’s side throughout this momentous episode of the war.

About the author: Allan Sinclair is the Curator of the Military Art, Aviation, Naval and Trophies Collections at the Ditsong National Museum of Military History in Johannesburg.

References

- Beevor, A D-Day the Battle For Normandy (London, Penguin, 2010)

- Gilbert, M Road To Victory, Winston S Churchill, 1941 – 1945 (London, Minerva, 1986)

- Smuts, J C (Junior) Jan Christiaan Smuts (Cape Town, Cassell & Company, 1952)

- Styen, R Churchill and Smuts: The Friendship (Johannesburg, Jonathan Ball, 2017)

- Churchill makes a day trip to Normany via World War Two Today.

- Great Contemporaries: Jan Christiaan Smuts via The Churchill Project

- Jan Smuts, Winston Churchill and D-Day via The Observation Post

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.