Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

It is fortunate for posterity that Group Captain Rupert Taylor, a Johannesburg businessman in 1964 became interested in the old Simon’s Town Seaforth Cemetery or the ‘Old Burying Ground’, as it is called. Like his war-time contemporary ‘Sailor’ Malan he began his service career in the Navy before switching to the Airforce during the Second World War. While in the Navy he used to occasionally sit under a plaque to Midshipman Hammill in this cemetery admiring the sea view. When he visited the cemetery many years later, he was dismayed by the all-round decay and dereliction. He started paying a monthly stipend to the Simon’s Town Municipality to as he called it, ‘at least stop the encroachment of weeds’. Reporter Carl Birkby then wrote an article for the Sunday Times called ‘Vanishing Africana …. written in a forlorn graveyard.’ This attracted much needed attention to the dismal state of this historical cemetery and the urgent need to intervene. In 1968 the War Graves Board informed the Municipality that it intended to restore the Simon’s Town Cemetery and establish a Garden of Remembrance in what used to be the Naval Cemetery. Work commenced in 1973 and the dedication ceremony took place in October 1977.

This Cemetery should feature high on one’s bucket list of places to visit in the Cape Peninsula as it offers something to anyone who has an interest in South African or British maritime history.

The Garden of Remembrance provides insight into the lives of Royal Navy seamen during the Victorian era. When one is safely ensconced on a large and luxurious ocean liner with all the requisite creature comforts, one easily forgets how dangerous and capricious the oceans may be to those on sailing ships. In this Garden of Remembrance there are numerous monuments, plaques and tombstones dedicated to sailors and soldiers who died when their ship or ship’s pinnace foundered in rough seas off the Cape Coast, or during armed encounters with hostile Arabs slave traders while trying to stop this trade off the East and West African coastlines.

There is also something quite unusual to South Africa, a monument to Russian sailors who died at Simon’s Town.

For the visitor interested in the art of sculpting, there is an elegant tomb designed by Sir Francis Chantrey, the foremost portrait sculptor of the Regency era.

For those recalling the memorable appeal ‘Women and children first’, the cemetery contains some graves of sailors and soldiers whose remains were subsequently reinterred here following the sinking of the HMS Birkenhead off Danger Point on that fateful night of 26 February 1852.

There is also a monument to Boer Prisoners of War who died while in captivity at Simon’s Town, prior to being shipped overseas to any one of the numerous Imperial Prisoner of War Camps in India, Ceylon, St. Helena and Bermuda.

Finally, there is that rare sight of two family mausoleums, architectural structures quite uncommon to most South African cemeteries.

Governor Simon van der Stel recommended to the Council of the VOC (Dutch East Indian Company) that a sheltered bay on the west side of False Bay, which he named Simon’s Bay, be used as a winter anchorage for ships of the VOC. The Company concurred and decreed in 1741 that it should be used for this purpose between 15 May and 15 August, annually. Following this decision, the hamlet of Simon’s Town slowly developed.

In 1814, during the second British occupation of the Cape, the Royal Navy transferred its headquarters to Simon’s Town giving a much-needed impetus to its growth. Around this time, it was recognised that the anchorage at Simon’s Town was comparatively safe in all seasons and therefore in some ways superior to Table Bay.

The expanding population necessitated a burial ground and the present site was granted to the Anglican Church. Later, part of a previous land grant to Captain Thomas Talbot Harington was added to the Old Burying Ground as the Dutch Reformed and Catholic precincts.

The Cemetery lies on the corner of Queen’s Road and Runciman Drive with entrances on both roads and is opposite to the naval base as one passes south to Glencairn.

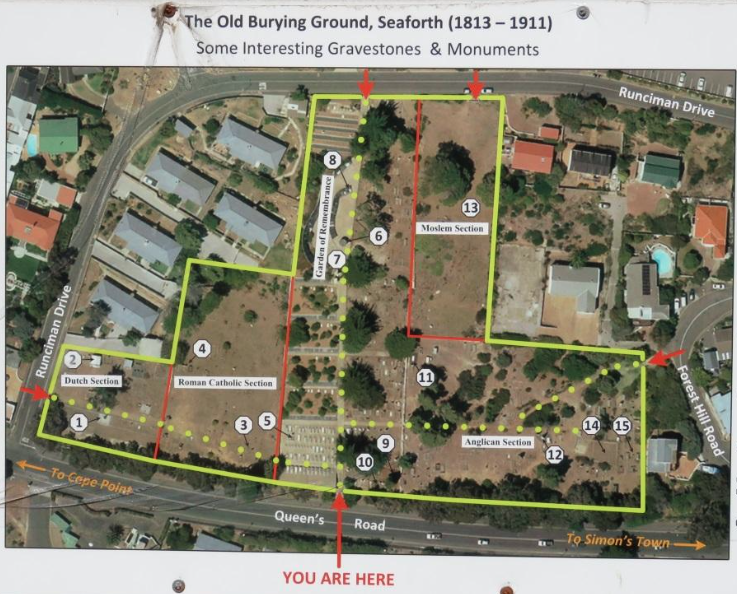

The Simon’s Town Historical Association erected an informative guide panel at the Queen’s Road entrance providing directions to some interesting graves. The Simon’s Town Museum also sells a pamphlet providing similar information. The entrances in Queen’s Road and Runciman Drive are linked by a paved pathway providing excellent access to and from the Garden of Remembrance.

Panel providing directions to various interesting and historical monuments and tombstones at the Old Burying Ground.

As one views the cemetery from Queen’s Road, the Dutch Reformed precinct is on the southern end indicated by ‘1’ on the Guide Panel. The Roman Catholic precinct is indicated ‘4’, the Birkenhead tombstones indicated as ‘6’, the Garden of Remembrance as ‘7’ and Lady Isabella Brenton’s tomb as ‘11’, the Russian monument and tombstones as ‘12’ and the allotment where sailors and boys from the HMS Owen Glendower were originally buried as ‘14’.

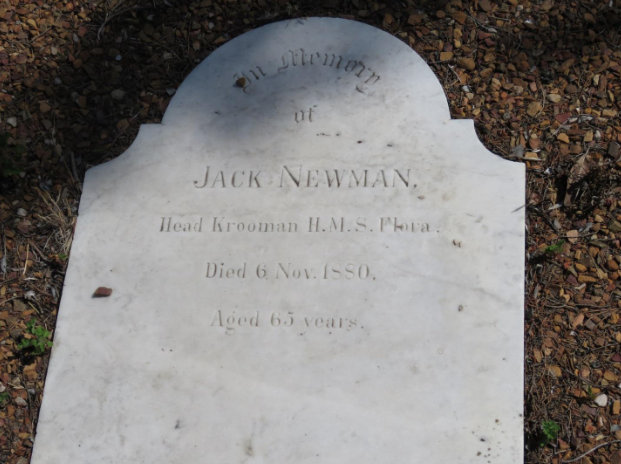

It is best to commence one’s visit at the Garden of Remembrance since this is where most historical graves are situated. Walk up the pathway to the more recent monument erected by the SA War Graves Board and read the names of the more than 30 Royal Navy ships stationed in South African waters during the 19th century. It is estimated that about 550 sailors, soldiers, marines and 50 Kroomen are buried here. ‘Kroomen’ is an interesting term which conveys the practice of the Royal Navy ships to include in their complement Africans from the Kru Nation on the African West Coast, who were all excellent small boat seamen, willing workers and relatively immune to malaria. The sailors often gave the ‘Kroomen’ colloquial names but over time a mutual respect developed.

Tombstone of Jack Newman, ‘Head Krooman’ of HMS Flora. (SJ de Klerk)

The oldest tombstone is that of Rear Admiral George Dundas who died on 8 August 1814, not long after he had purchased the house belonging to the widow Hurter, which later became Admiralty House.

The visitor will find some very poignant monuments and plaques to seamen who lost their lives on the various Royal Navy Ships off the coast of Africa.

One such monument reads, ‘HMS Nerbudda. H. A. Kerr Commander. 13 Officers, 120 Men. Lost 1855.’ The reverse side states, ‘Standing out of Algoa Bay June 10th 1855. Terrific gales soon after blew. Not heard of since.’

Monument to HMS Nerbudda, lost with all hands on 10 June 1855 off Algoa Bay. (SJ de Klerk)

Most people have heard or read of the Royal Navy patrolling the West and East African coastlines to stop the slave trade during the Victorian era. It is only when perusing the various tombstones and plaques at this cemetery that one comprehends this did not happen without heavy sacrifice from the sailors, marines and soldiers concerned.

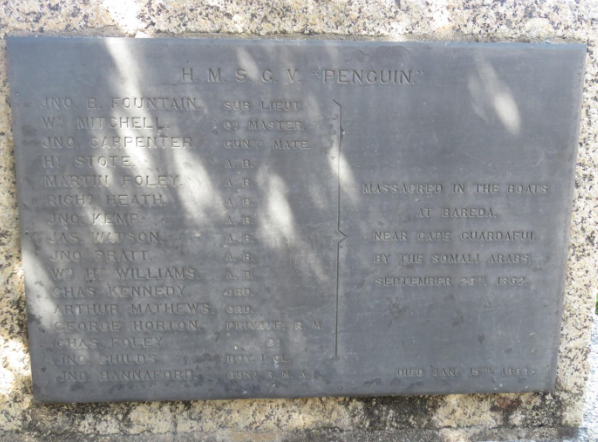

There is one plaque which records HMS Penguin’s campaign against Arab Slavers; ‘Massacred in the boats at Bareda. Near Cape Guardafui. By the Somali Arabs. September 26th 1862.’

Service on the East African anti-slaving patrol was an unpleasant and dangerous experience and it was generally expected that no sailor should perform this duty for longer than three years. Life on the small boats or pinnaces, as they are called in naval parlance was particularly unpleasant. Sometimes these boats were away from their ship for several weeks, often in rough water, with inadequate food and water, without medical attention, sleeping amongst swarms of mosquitoes while searching the river mouths and inlets for slave depots. Many of the crew suffered from malaria and other tropical ailments. The Arab slavers often fought desperately and the fifteen seamen on the cutter and whaler boats of HMS Penguin were attacked and killed when landing ashore to look for drinking water on the Somali coast. Overall the duties were tedious with incessant boarding of dhows and prolonged inspections often resulting in acquittal and release.

Plaque to Seamen of HMS Penguin massacred at Bareda, Cape Guardafui. (SJ de Klerk)

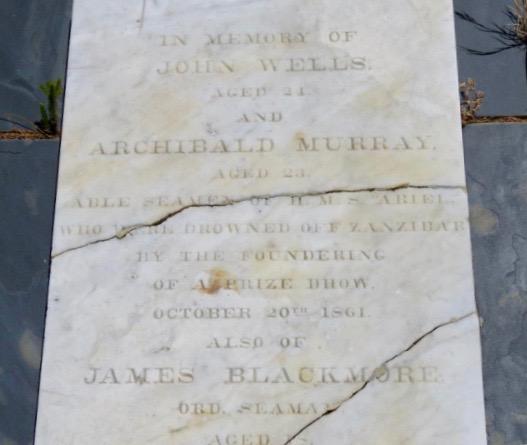

Close by there is a similar one, ‘In memory of John Wells, aged 24 years, and Arthur Murray, aged 23 years. Able Seamen of HMS Ariel who were drowned off Zanzibar by the founding of a prize dhow, October 20th 1861 – also of James Blackmore, Ordinary Seaman, aged 18 who died March 29th 1862, from wounds received in an encounter with the Northern Arabs.’

Plaque to seamen who drowned off Zanzibar in 1861 due to the foundering of a prize dhow. (SJ de Klerk)

The third plaque to Acting Pay-master John B. Sevecke is equally tragic but very interesting and reads, ‘Drowned in attempting to cross the Bar of the Kongoni River, June 1860, for the purpose of communication with Dr. Livingstone.’ As Carl Birkby states in his article, ‘A casual reference to a man then little known but who was to have his name linked forever with Africa.’

Slightly above the monuments placed in the center of this Garden of Remembrance is the final resting place of five casualties who perished when HMS Birkenhead sank on 26 February 1852 and whose remains were reinterred here in 1993 and 2002. The tragedy of the Birkenhead is well known but as she is South Africa’s most famous maritime disaster, a brief re-telling of her journey and subsequent sinking may be informative. She sailed from Cork in Ireland in late December 1851 with a complement of 23 officers and 469 soldiers to assist Sir Harry Smith in the Eighth Frontier War (1850-1853) then being waged in the Eastern Cape. After a journey of more than 50 days she stopped over in Simon’s Town to replace coal and provisions and receive dispatches for Sir Harry Smith. She left Simon’s Town at 18h00 on 25 February on her voyage to Algoa Bay (now Port Elizabeth) and East London to land the troops on board.

The sea was flat and the ship proceeded at 8.5 knots per hour. Most of the men were asleep below when at 02h00 a violent shock was felt and in an instant the lower deck flooded drowning many men in their bunks and hammocks. All the surviving officers and men went up on deck. The senior officer, Lieutenant Colonel Seton immediately summoned his officers and stressed the importance of maintaining order and discipline. The men were commanded to fall in and await orders while 60 men were sent to man the pumps. At this moment Ship Captain Salmond made the grave mistake of ordering the Birkenhead to be put astern to pull her off the rocks, which caused the hull to rip open further. The inrush of water swamped the boiler fires and the vessel began to break up. After some difficulties the men managed to release two cutters and a gig filled with women and children. Captain Salmond then shouted that anyone who could swim must save himself by jumping overboard and making for the boats. The soldiers were instructed to stand firm so as not to swamp the boats. The Birkenhead rapidly disintegrated and within twenty five minutes of striking the rock only the topmast and topsail yard were visible above the water with about 50 men clinging to them. It is estimated that of the 638 people on board only 193 were saved.

Last moments on board the disintegrating HMS Birkenhead with the soldiers standing firm. It is unlikely the assembled soldiers would be dressed in their uniforms as shown in this painting as they would have been asleep and wearing undergarment in the moments before the ship struck the rock.

There are interesting symbols on some of the plaques and tombstones in the Garden of Remembrance. The enclosed example shows a hand arising from a grave holding a flowering plant, which symbolises the Christian belief of resurrection after death.

Symbol on a Tombstone in the Garden of Remembrance reflecting resurrection after death. (SJ de Klerk)

Several tombstones are attractive examples of hand engraved ones. The particulars of Thomas Ambrose, Sculptor, sometimes spelt Ambroes, are engraved on some of them. It would be interesting to know more about Ambrose and whether he was an artisan in the naval dockyard or whether he specialised in sculpting tombstones.

Attractive tombstone engraved by Thomas Ambrose in memory of Midshipman John Lyon of HMS Minden, erected as a tribute of esteem by a sincere friend. (SJ de Klerk)

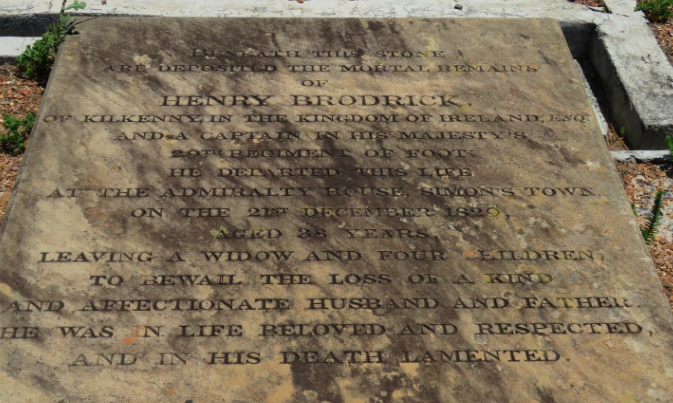

There is also an attractive tombstone for Henry Brodrick, Captain in the 29th Regiment of Foot, engraved by Crake of London. His fulsome epitaph in the Victorian tradition reads, ‘Beneath this stone are deposited the mortal remains of Henry Brodrick …. Leaving behind a widow and four children to bewail the loss of a kind and affectionate husband and father. He was in life beloved and respected and in his death lamented.’

Tombstone of Henry Brodrick from Kilkenny and Captain in the 29th Regiment of Foot. The tombstone was sculpted by Crake of London. (SJ de Klerk)

Adjacent to the boundary wall separating the Garden of Remembrance from the Anglican precinct is the noteworthy tomb of Isabella Brenton, the wife of Rear Admiral Sir Jahleel Brenton, who was the first occupant of Admiralty House. His first name ‘Jahleel’ means ‘Hoping in God’ and apparently, he was a deeply religious person. Her white marble tombstone was designed by Sir Francis Chantrey, who was considered the foremost British portrait sculptor of his time. It is inscribed with the moving epitaph, ‘Sacred to the Memory of Isabella, the wife of Sir Jahleel Brenton, Commissioner of H. M. Navy Cape of Good Hope, OB 29th July 1817, Aged 46 years. She was to her beloved husband the richest treasure of indulgent heaven.’

Chantrey began sculpting in marble in 1805 at the age of twenty-four and before his death in 1841, executed an immense number of memorials.

To date, only two tombstones by Chantrey have been located in South Africa; that of Isabella Brenton’s and a particularly attractive one for Diana Warden, the wife of Francis Warden, Chief Secretary to the Government of Bombay, who died on 28 October 1816 at Cape Town and whose tombstone is now preserved in the courtyard of the Iziko Slave Lodge.

During her fatal illness Isabella Brenton was attended to by that very interesting character, Dr. James Miranda Barrie (1795-1865) who is buried at Kensal Green Cemetery, London. The ‘Concise Guide of the Kensal Green Cemetery’ describes Dr. Barry as follows, ‘Army doctor and hospital reformer who served in India, South Africa, Mauritius, the West Indies, St. Helena, Malta, Corfu, the Crimea and Canada; one of the first modern surgeons to perform a caesarian section successfully; trained and practiced as a man, only discovered to be a woman after death.’ It is more likely that she would be termed ‘gender neutral’ today. At Cape Town on 25 July 1826, Dr. Barry completed the first successful caesarian section on the wife of T. F. Munnik, as both mother and child survived. Barry did not require any payment for conducting this procedure other than requesting the baby to be named after him. Interestingly, forty years later James Barry Munnik gave in turn his names to his godson James Barry Munnik Hertzog, who subsequently became the third Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa.

The large tomb is that of Lady Isabella Brenton designed by Sir Francis Chantrey. The adjacent small tombstone is that of Dacres Brenton von Donop (1845) infant son of Louise and Edward, nephew of Sir Jahleel Brenton. (SJ de Klerk)

Nearby and still in the Anglican precinct is an unusual monument to deceased Russian sailors. The monument lists the names of 23 sailors and the epitaph in both Russian and English reads, ‘Sacred to the Memory of Russian sailors, participants of maritime expeditions of the glorious Russian Fleet (1809-1865). Far away from the Motherland, at the foot of the African continent they found their last resting place …’ Adjacent to this monument are the impressive tombstones of Fleet Navigator Nikolau Petrovil and Seaman Pyetra Reshyeka who both died in 1865.

Monument to deceased Russian Sailors with two Russian tombstones on the right. (SJ de Klerk)

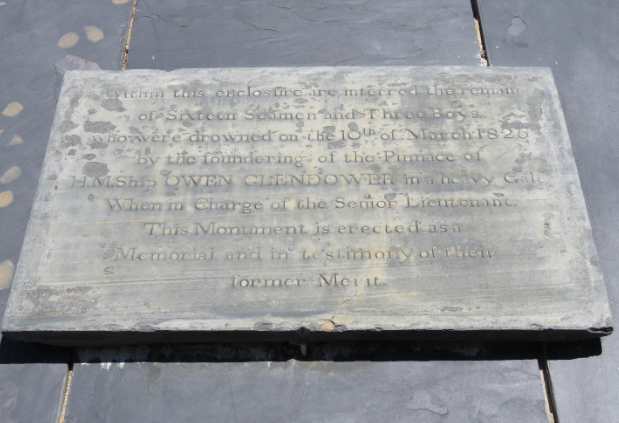

Close to the Russian graves is the allotment where initially sixteen seamen and three boys from the HMS Owen Glendower were buried, following the sinking of their pinnace in a heavy gale on 10 March 1826 whilst conveying them from the West Dockyard to their ship. Their remains were subsequently reinterred in the Garden of Remembrance and this allotment is now reserved for the interment of ashes.

Plaque to the memory of sixteen seamen and three boys who drowned due to the foundering of the pinnace of HMS Owen Glendower. (SJ de Klerk)

As one meanders south from the Garden of Remembrance to the Dutch Reformed precinct keep an eye open for the graves of Italian workmen buried in the Roman Catholic precinct. Many were employed by Sir John Jackson in the building of the East Dockyard between 1900 and 1910.

Also look out for some interesting trees signposted in the cemetery. One will find, amongst others, Cedar trees from the Southern Mediterranean, as well as Flowering Gum trees from Australia.

Upon reaching the Dutch Reformed precinct at the southern edge of the cemetery one immediately notices the large monument to the memory of deceased Boer Prisoners of War interred here. This wording in Dutch on the monument reads, ‘Ter Gedachtenis aan Boeren Krygsgevangenen alhier begraven. Anglo-Boeren Oorlog 1899-1902.’ It is estimated that approximately 160 Boer prisoners were interred in this precinct.

Monument to Boer Prisoners of War interred in the Dutch Reformed precinct. Note the two family vaults on either side behind the monument. (SJ de Klerk)

Most Boer prisoners of war were transported by rail to Cape Town where they were interned at Greenpoint and Simon’s Town prior to being shipped to a prisoner of war camp at St Helena, Bermuda in the West Indies, Ceylon now Sri Lanka, or India. The British authorities deemed it best if the prisoners of war were sent to camps abroad where there would be no risk of rescue from roving Boer Commandos.

The first Boer Prisoner of War Camp at Simon’s Town was erected on the Naval Recreation Ground adjacent to the Martello Tower containing about 450 prisoners, housed eight persons per military tent. The area was considered suitable as the ground was flat and close to the sea for recreational bathing purposes.

Later an almost identical but larger camp was erected at Bellevue, now part of the Simon’s Town golf course. To the military it had the advantage of being more distant from Simon’s Town.

The first batch of about 5 000 Boer prisoners of war arrived at Deadwood No.1 Camp on St Helena in April 1900. Ceylon’s first camp Diyatalawa was filling up during the following August where about 5 000 prisoners were interned during the war. Boer prisoners of war started appearing in India in April 1901 where ultimately about 9 000 burghers were detained. The camps on Bermuda Island were the last to be occupied by about 4 600 burghers.

According to Colin Benbow there is reason to believe that had the war continued longer, Boer prisoners of war would have been sent to Antigua in the Caribbean, where a camp was in the process of being prepared.

In total approximately 25 000 men and boys were interned in the various overseas camps by the time the war ended. It is estimated 1 000 of them failed to return home.

The Simon’s Town Historical Society must be congratulated for their sterling efforts to maintain this historical cemetery.

The author also wishes to express his appreciation to members of this Society who kindly provided him with a copy of Carl Birkby’s article which appeared in the Sunday Times during the late 1960’s.

Main image: View of False Bay from the Garden of Remembrance in the ‘Old Burying Ground’, Simon’s Town. (SJ de Klerk)

About the author: SJ De Klerk held many senior positions in HR during a distinguished career in the private sector. Since retiring he has dedicated time and resources to researching, exploring and writing about South Africa's historical cemeteries.

Sources

- Benbow C. (1982). Boer Prisoners of War in Bermuda. The Bermuda College, Devonshire Bermuda.

- Birkby C. (Not dated). Vanishing Africana …… written in a forlorn graveyard. Article in the Sunday Times.

- Brock B. B. & B. G. & Willis H. C. (1976). Historical Simon’s Town. Published by A. A. Balkema for the Simon’s Town Historical Association.

- Cheswell M. (2003). The Cape Squadron, Admiral Baldwin Walker and the Suppression of the Slave Trade. Dissertation in fulfillment of the degree Master of Art in Historical Studies, University of Cape Town.

- Domisse B. (2005). Admiralty House Simon’s Town.

- Friends of Kensal Green Cemetery. Kensal Green Cemetery - A Concise Guide. 2012.

- Kayle A. (1990). Salvage of the Birkenhead. Southern Book Publishers, Johannesburg.

- Knox-Johnston R. (1989). Cape Horn : A Maritime History. Hodder & Stoughton, London.

- Kruger D. W. Editor. (1983). James Barry in Dictionary of South African Biography Volume 2. Human Sciences Research Council. Tafelberg Publishers, Goodwood, Cape Town.

- Langham-Carter R. R. December (1955). A Work by Sir Francis Chantrey in Africana Notes and News Vol. XI, No. 9. Africana Society, Africana Museum, City of Johannesburg.

- Pamphlet produced by the Simon’s Town Historical Society. (Non dated) The Old Burying Ground (1813 – 1911) Seaforth - Simon’s Town.

- Read. A. E. (Not dated 1999?). Simon’s Town and the Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902. Special Edition to Commemorate the Centenary of the Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902 As it Affected Simon’s Town. Simon’s Town Historical Society. Zip Print.

- Van den Heever C. M. (1946). General J. B. M. Hertzog. A. P. B Bookstore. Johannesburg.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.