Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In a recent article published by the author (click here to view), reference was made to a modern photographic phenomenon, namely “found photographs”. In short: “Found photographs” are discarded vintage photographs typically found at charity stores, car boot sales, flea markets or antique fairs. As a single image, any “found” or the converse thereof, “lost” photograph, has sadly lost its original context when viewed by a total stranger who would have no context to the photograph. A different context can however be provided again when “lost” images are clustered together into a theme, such as the one presented in this article.

This article focuses solely on the pavement photographs taken on South African streets prior to the 1970s. At a recent antique fair, the author obtained a discarded photo album, containing several pavement photographs.

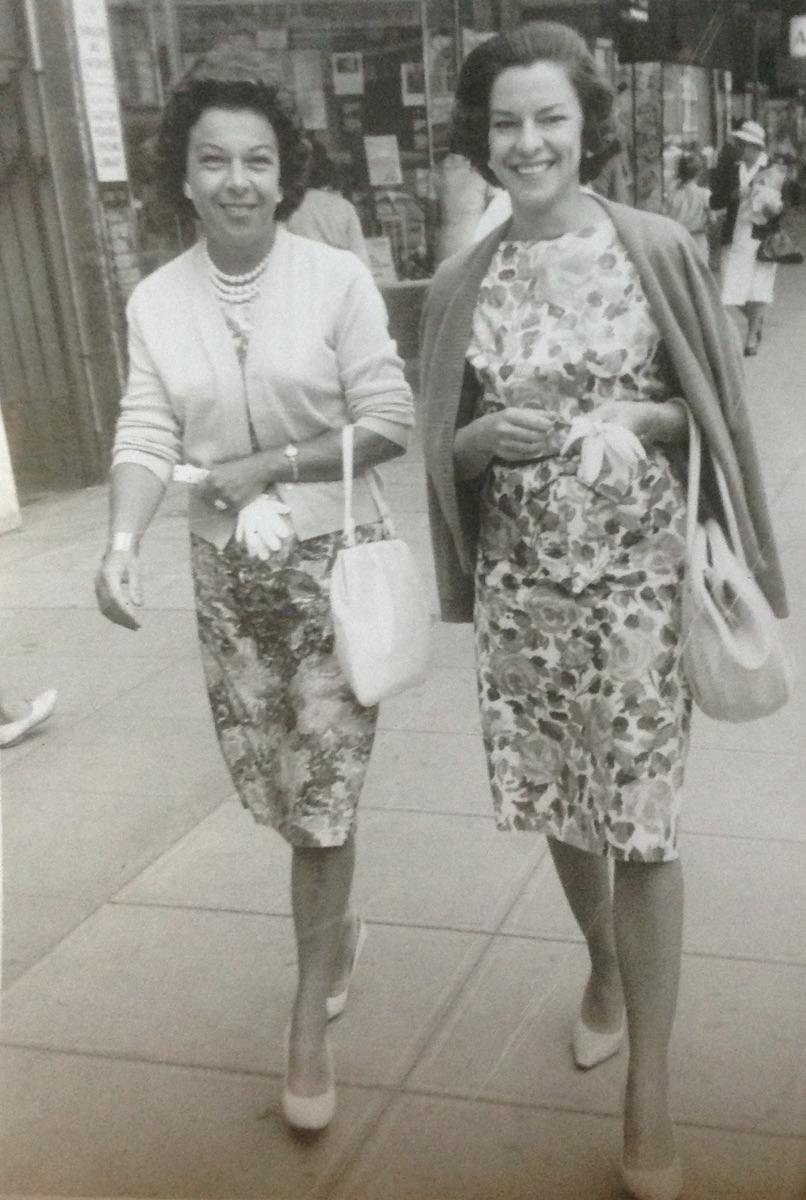

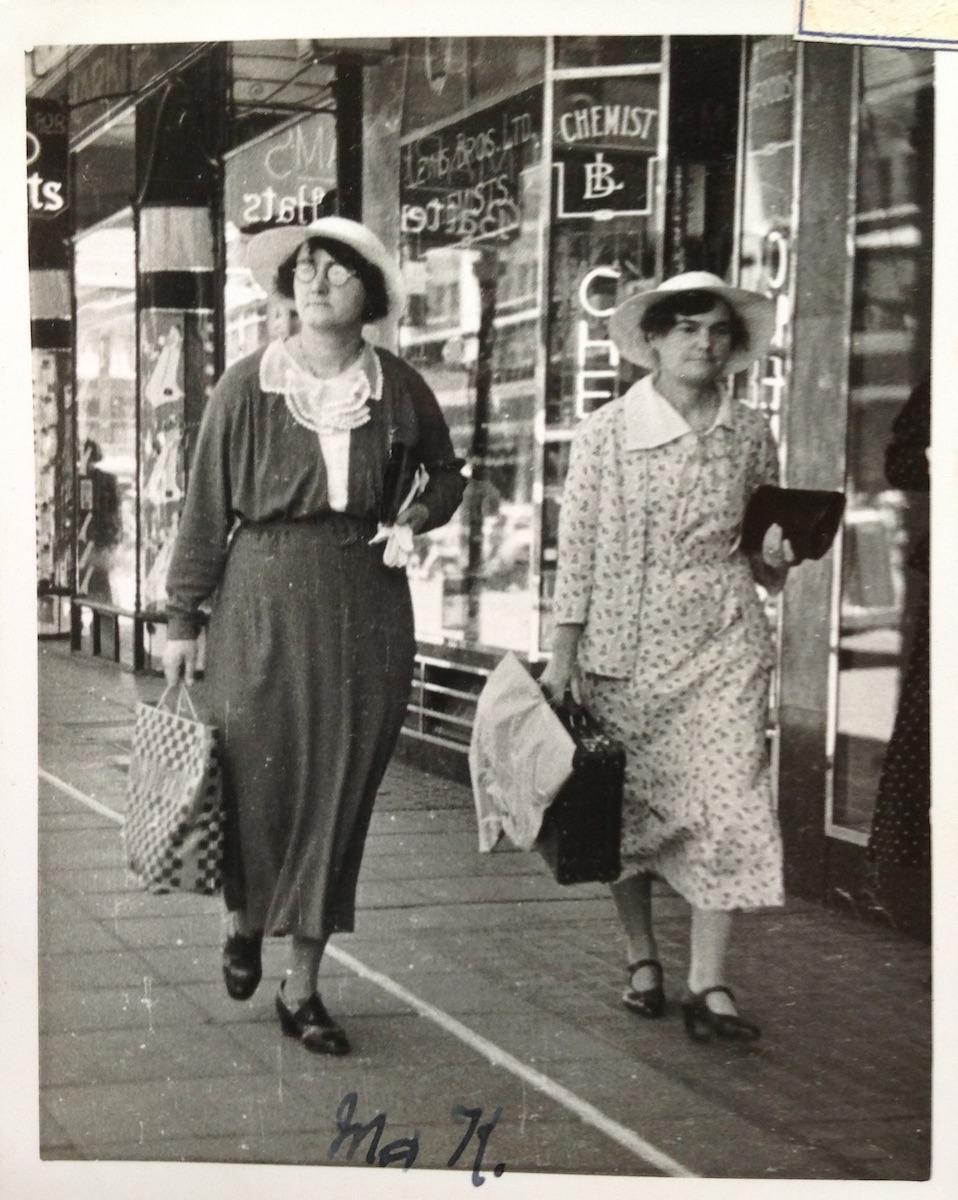

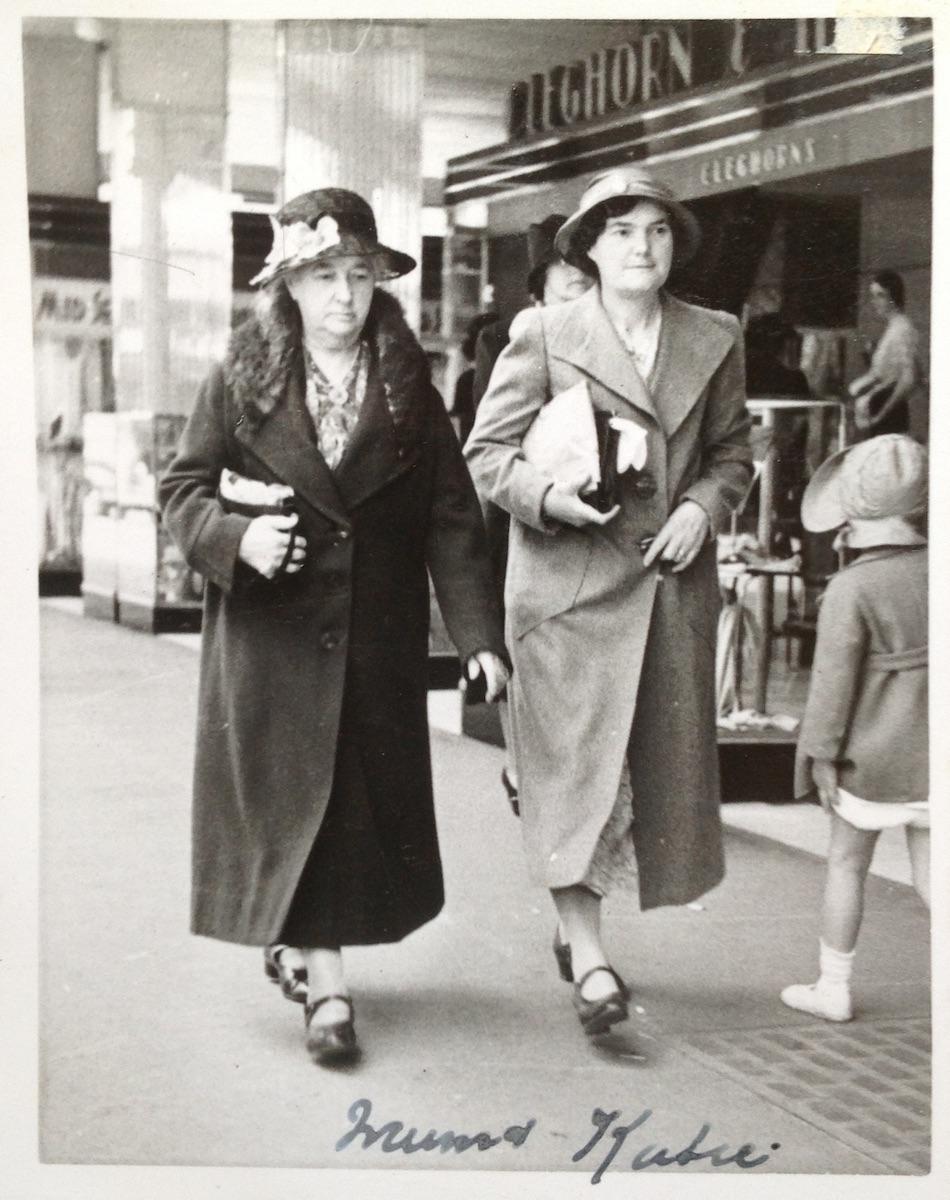

Two elegant ladies walking down a street in Durban. They can clearly be seen “courting” the camera.

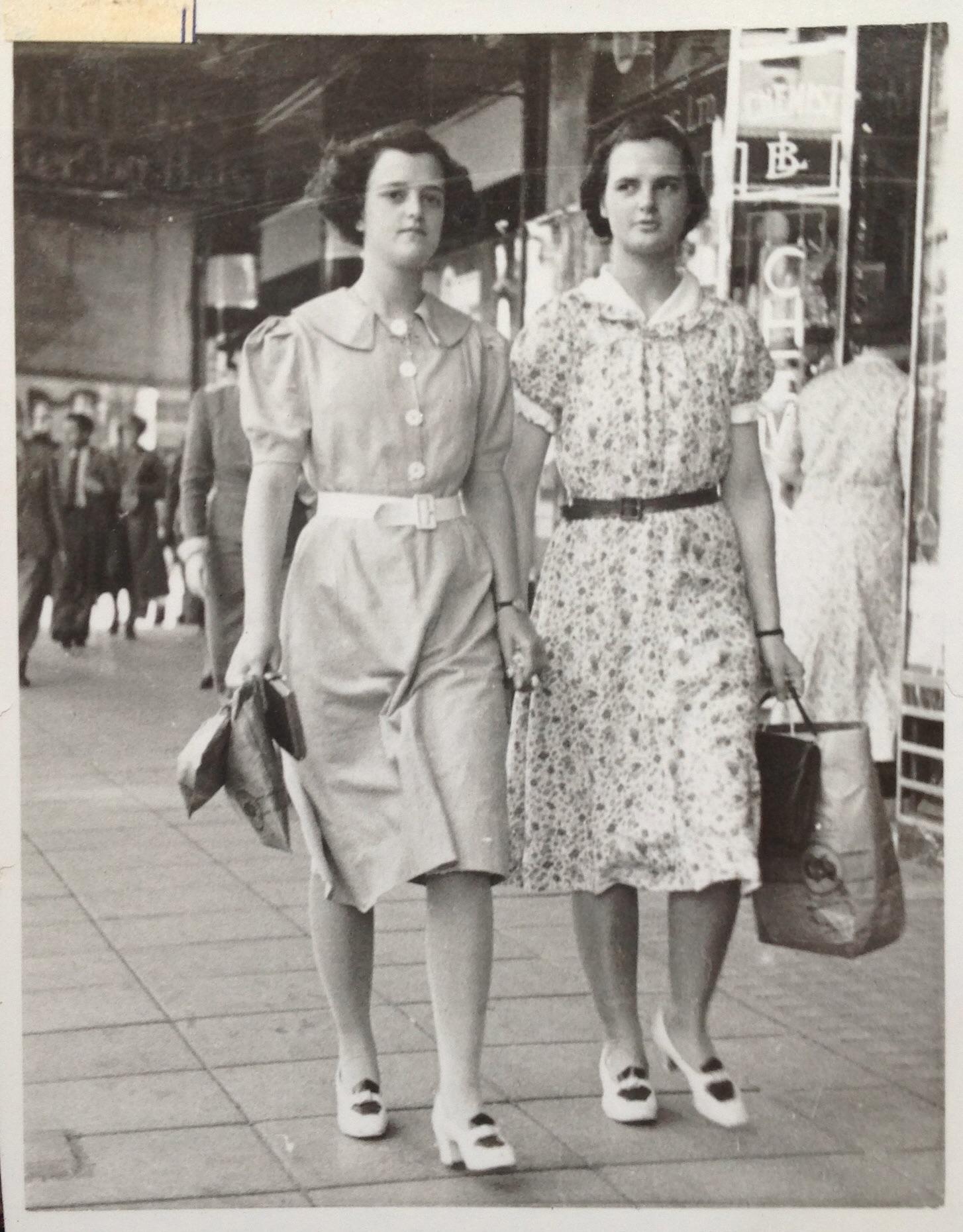

Two young ladies walking down a street in Johannesburg. They both seem somewhat uncertain as to how to respond to the camera’s attention.

What are pavement photographs?

Photographers continuously had to look at renewing themselves and come up with competitive and creative alternatives in generating additional income streams. Instead of waiting for customers to come into their refined space, the photographic studio, photographers expanded to the urban pavements where they literally set themselves up on the pavements of the larger South African urban cities.

Pavement, or sidewalk photographers, would mostly take candid photographs of individuals, couples, families and other groups walking down the street, mostly unaware of the cameraman’s activity.

The resultant images also became known as impromptu, candid or walking pictures. The photographer, or an assistant, would then hand ‘the subject’ that has just been randomly photographed a numbered ticket with an invitation to drop by their studio later to buy a copy of the photograph. This trend continued in South Africa into the late 1960s.

Pavement photography is a sub-genre to street photography. Street photography simplistically can be defined as documentary photography that features subjects in candid situations within public places such as streets, parks, beaches, malls, political conventions and multiple other settings. Street (or Urban) photography therefore does not necessitate the presence of a street or even the urban environment. Though people usually feature directly in street photographs, some photographs may not feature any people in that the image may be an abstract of an object or environment.

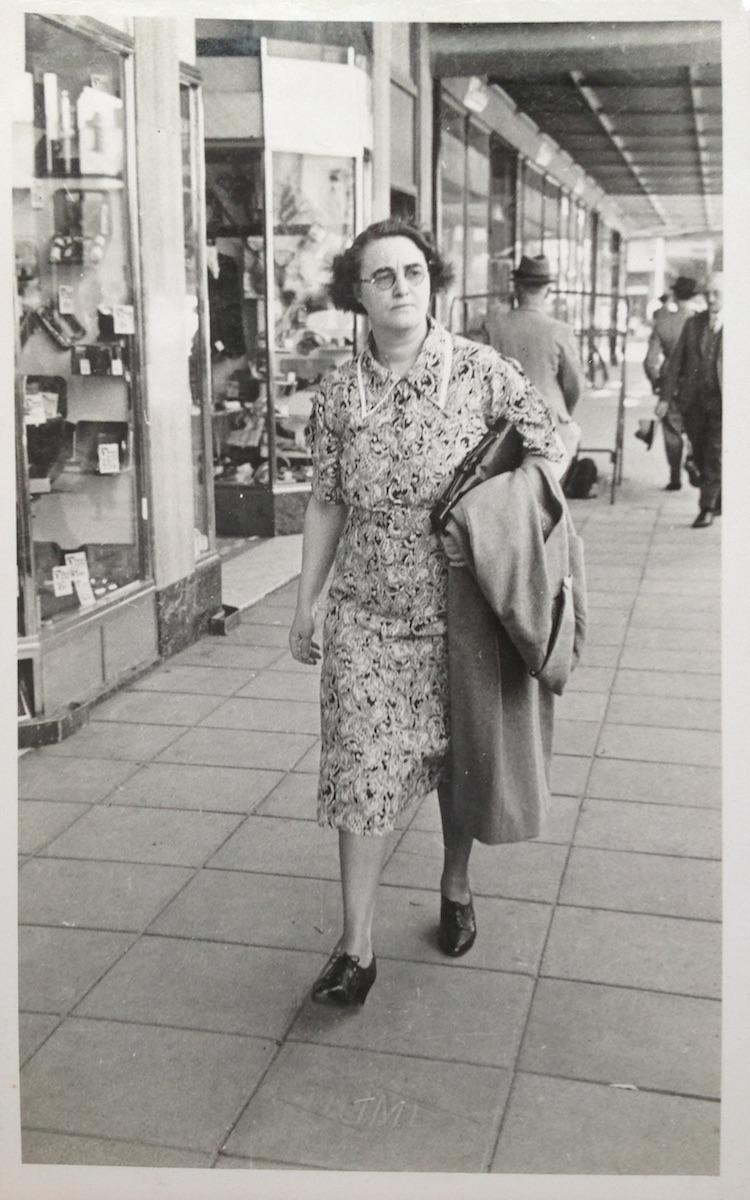

The same lady captured at different locations in Johannesburg. The one image was clearly taken mid-winter.

Pavement photographers certainly did not have a social or artistic purpose in mind in that their primary purpose was a commercial one. Some of the images, as can be seen from the images included in this article, also had both poor composition or focus.

There is an element of voyeurism involved in pavement photography. Pavement photographs are images produced at a decisive or poignant moment, unmanipulated, showing the often unaware subjects “as is” in the moment of capture.

Pavement photographers by nature would also have become great people watchers. Overtime, they would have got a sense which subject would have been more likely to buy images. Some subjects would therefore have been clear targets, whilst others may have been ignored.

The author has yet to see an image taken of any other South African race group, other than the white population. Our country's segregationist past no doubt has something to do with this but further research is required to unpack the complexity behind this phenomenon.

Pavement Photography evokes a kind of social commentary and as such it is not just a point-and-shoot for whatever-comes-up exercise.

All these images were taken in Johannesburg. The image in the wooden frame is of Kotie Mulder.

The quickness of it, that is, the lifting of the camera and shooting in the thick of things, does however not mean that artistic imagination and reflection has not taken place. Much of the situational assessment happens before looking through the viewfinder and pressing the shutter. The skilled pavement photographer learned to recognize situations, anticipated behavior, knew the location or at the very least would have understood what was visually compelling given various possible elements that converged at a particular point in time.

Pavement photography is therefore an approach to picture-taking that was situational, intuitive and reactive. It did not come about due to contemplation or careful planning.

There’s some debate over who the “father” of street photography was. Although the Frenchman, Eugene Atget, is often granted this title, his work was mainly architectural, placing people second.

South African based photographers copied their Western counterparts in this form of economic activity during the mid to late 1930s. Although it still needs to be determined who the first South African pavement photographer was, or when the first pavement photograph was taken, it is known that one Vancouver based street photographer, Foncie Pulice, had been active as a street photographer as early as 1934. He created around 15 million images in his 45-year career (until 1979) – mostly because he stuck around the longest.

But there’s another, lesser-known name that enters the picture (pardon the pun) as early as, if not earlier than Atget, namely the Scotsman John Thomson.

Thomson (1837 – 1921) began photographing the London streets after returning from his photographic travels to the Far East during 1872. His focus was on the London poor who made the London streets their home.

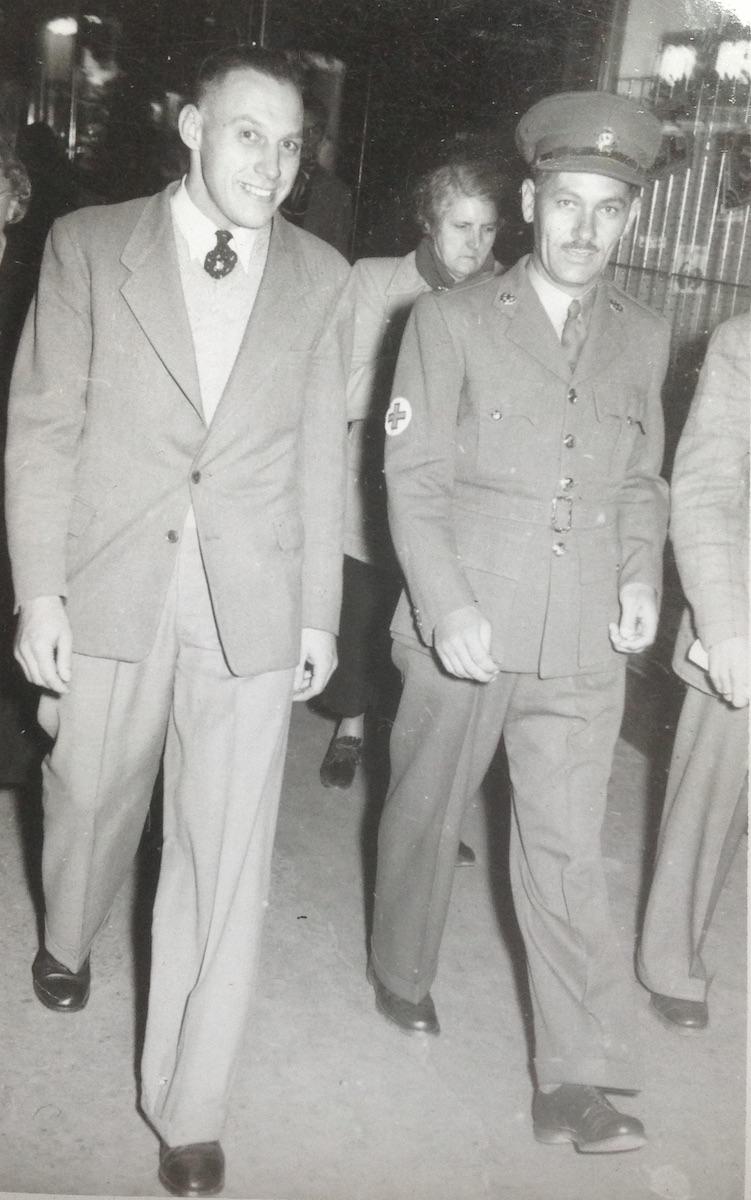

Men seem to have been targeted less by pavement photographers than what woman would have been. The first image above, taken in Port Elizabeth, confirms that pavement photographers were also at work after sunset.

Unlike the often sneaky and sometimes downright invasive pavement photography, the technology at the time meant that Thomson had to get to know his subjects. Due to longer exposure times required then, photographs could not simply be snapped in that permission had to be obtained from the subjects first prior to the heavy equipment being set up.

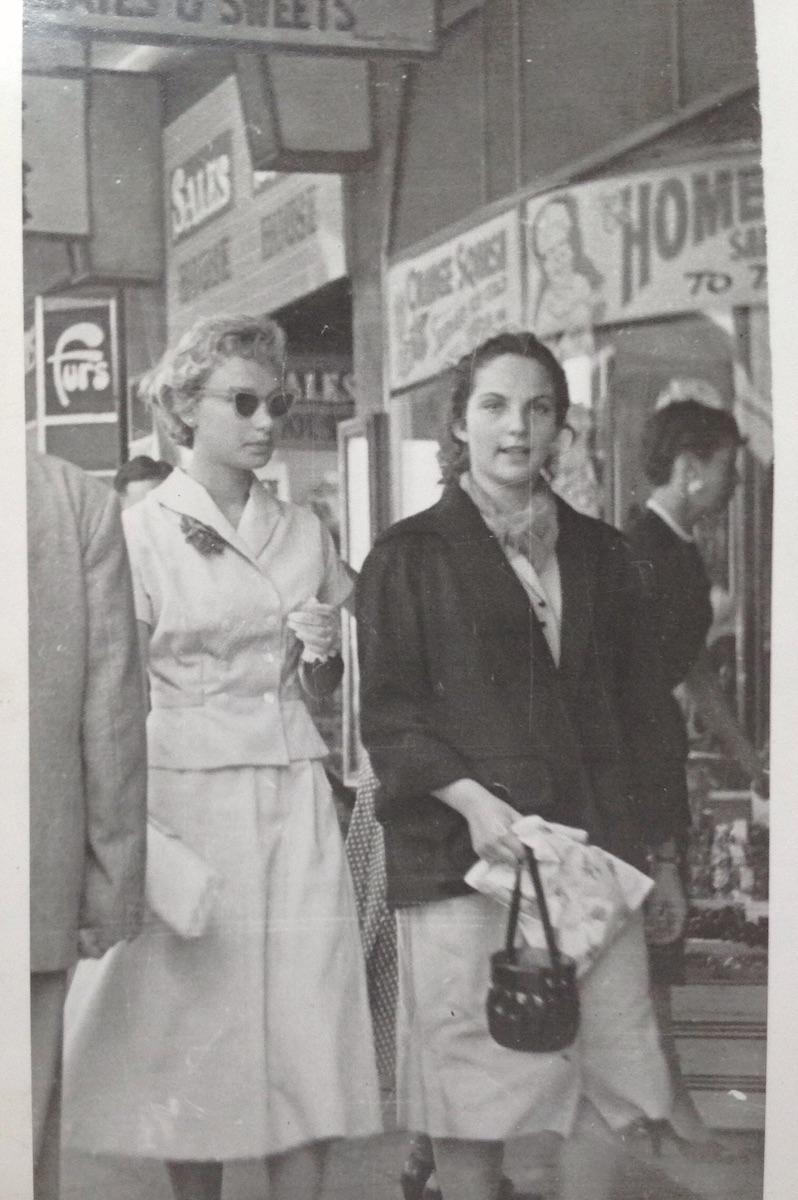

Though referred to as candid photography, not all photos were candid in that some “pavement strollers” clearly courted the camera. They sought out the photographer and can be seen making eye contact with the camera full-well expecting them to be photographically captured. In one of the photo albums obtained, this aspect is confirmed in that the owner of the album, one Katie, over a period of time collated as many images possible taken of herself and her shopping companion of the day.

All the images above show Katie with her shopping partner of the day in Johannesburg

Only a small number of photographers captured their details on the back of the photographs once printed. To date, the author has only identified five such photographic studios, namely:

- Johannesburg: Film Tests – They seem to have had two studios based at 94B Pritchard street (opposite the supreme court) and at 68 Joubert street;

- Johannesburg: The new movie snaps – 9 Moseley buildings, corner Rissik and President street;

- Johannesburg: Foto Fliks – Royal Arcade, Pritchard street;

- Durban: Film Tests Photographers – 20 Plowright lane;

- Port Elizabeth: Colorado Studio – 4th floor, Capitol buildings (Above the CTC Bazaar);

Pavement photographers were also active in Adderley street in Cape Town as early as the 1930s in that the author has seen some photographs taken of sailors visiting the city.

Where else were pavement photographers’ active in South Africa? Without a doubt, they would also have been active in Pretoria. This evidence still needs to be found. This then also begs the question – would pavement photographers also have been active in smaller cities such as East London, Nelspruit and Bloemfontein?

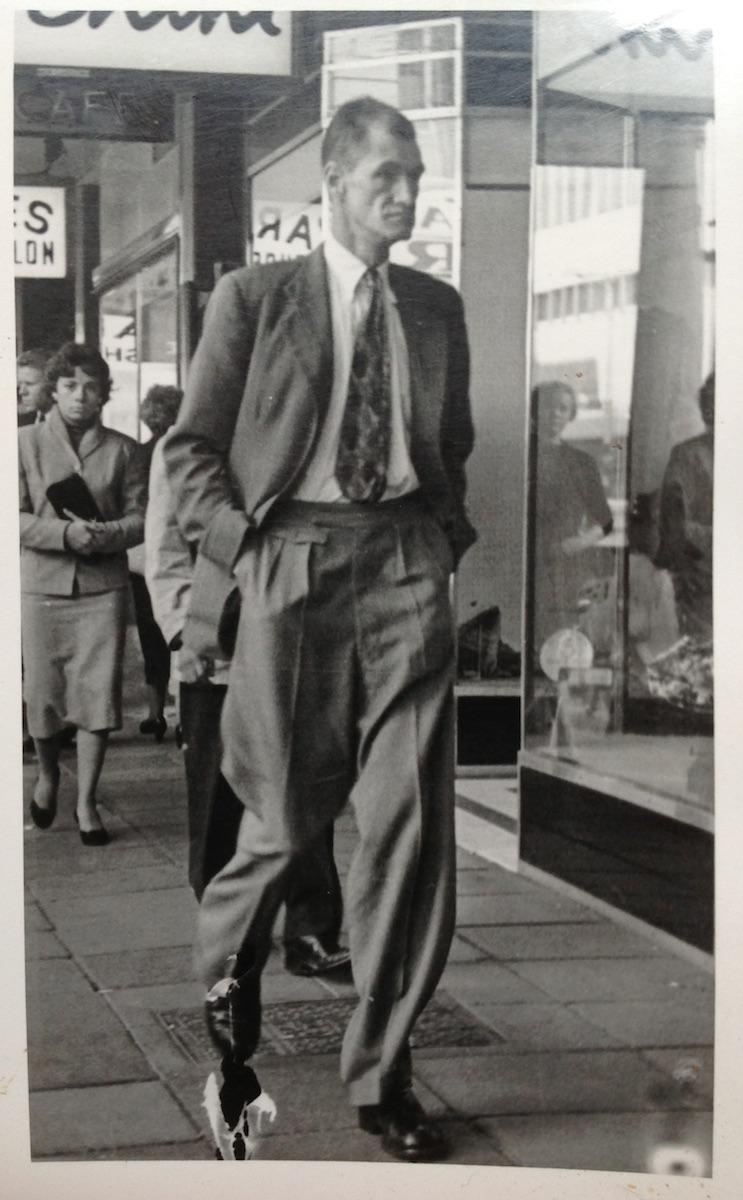

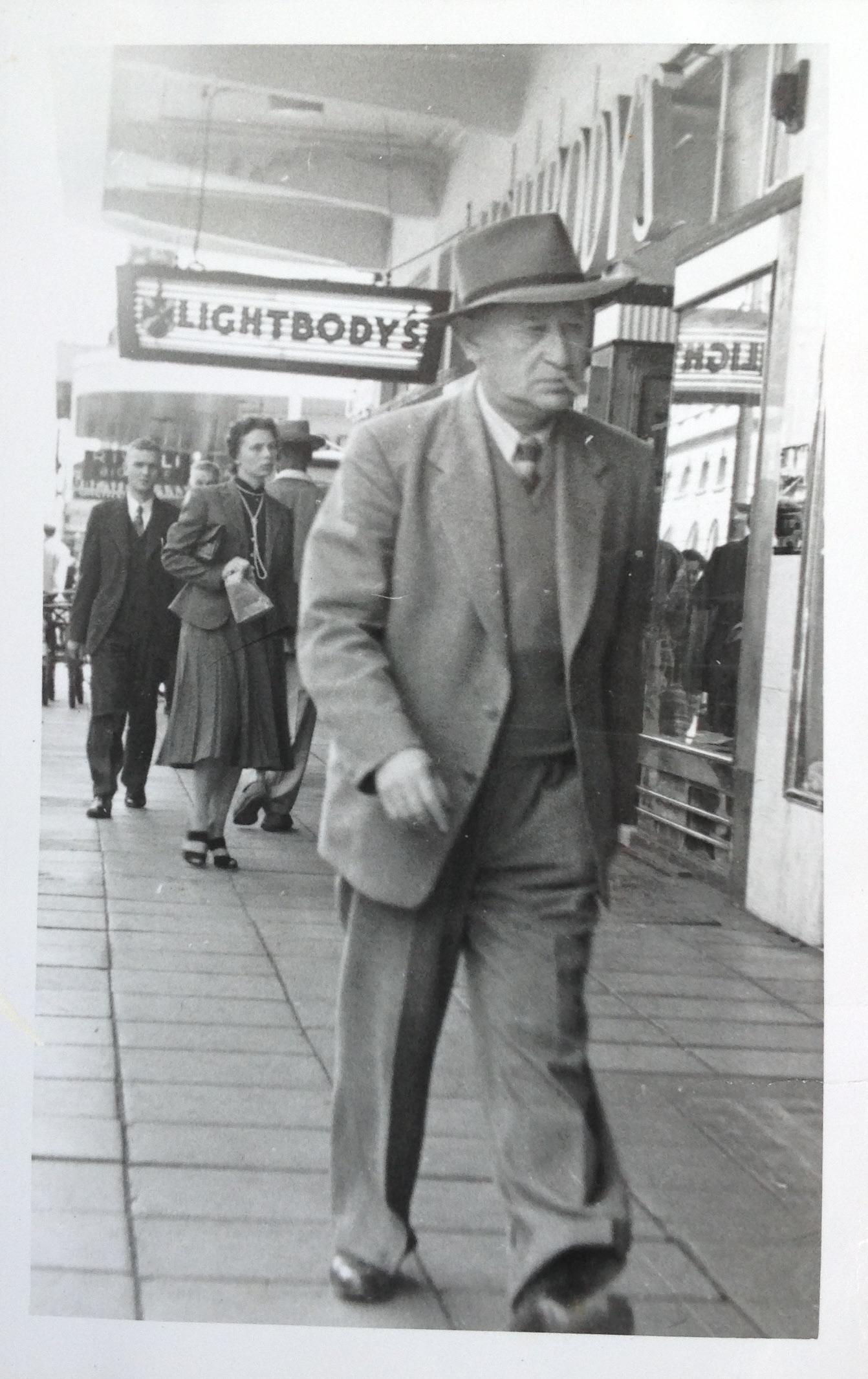

Today the photographs are of interest in that they provide some insight in terms of fashions of the time, the types of businesses around, shops fronts etc. Shop fronts, which today provides us with a relatively good insight of the shop set-ups and shopping behavior, were unintentionally captured in the process. One of the aspects these images also confirm is that pavements then were neat and tidy unlike the obstacle courses citizens are faced with today.

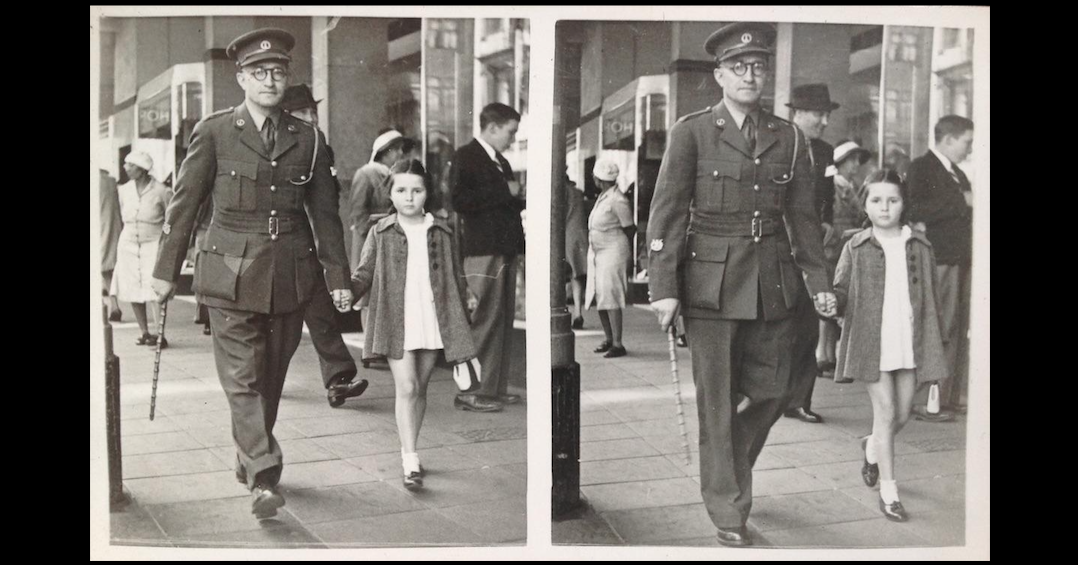

Some photographers took two images in quick succession allowing the individual being photographed to select one of the two images. In many instances, the individual/s photographed elected to buy both images. In the image above, the little girl was clearly coached by granny Katie to “court” the camera.

Identified on the images included in this article for example are:

- Cleghorn & Harris. Described as a high-class departmental store, they were based in Eloff street in Johannesburg; Built during 1939, the shop windows were a merchandising tour de force of non-reflecting concave-shape glass fronts that added the sparkling quality of modern design to Eloff street on the eve of the Second World War

- Lens Bros Chemist. Could not be determined where they were based yet;

- On one of the images, a Johannesburg based photographic studio in Eloff street can be observed. The photographer therefore stood outside his studio capturing images of passers-by.

The question arises, what was the “hit” rate? In other words, what percentage of photographs captured daily were eventually purchased by the “pavement strollers”. The author suggests that this figure would be well below 20%.

The search continues in identifying as many South African based pavement photographers as possible.

The next article will focus on another genre of street photography, namely beach photography.

Image taken in front of the photographer's studio in Eloff street

About the author: Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. He is also in the process of cataloguing Boer War stereo images produced by a variety of publishers. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources

- Bruwer, C.J.M. (2002). The Inner Court – 2002 Survey, (The Heritage Register).

- Duong, O. (2016). 3 Misconceptions of street photography (PetaPixel)

- Fenley, S. (2009). Sidewalk photographers. (Shades of the Departed)

- Górdova, N.I. (2010). The difference between candid and street photography (Eric Kim)

- Grifantini, L. (2016). Street photography on the beach. (Street Hunters)

- Hardijzer, C.H. (2018). Snapshot photography – Automobiles photographed in South Africa between 1920s and 1960s. (The Heritage Portal)

- Touchette, A. (2015). What is street photography. (Envato Tuts)

- Unknown (Extracted 17 August 2018). What is street photography – A simple and surprising answer to a complex question. (Inspired Eye)

- Vanalogue (2013). Street Photography. (Vanalogue)

- Wikipedia.org (Street photography)

- Wikipedia.org (Peoplewatching)

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.