Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

It was forty-five years ago (1970) that the Johannesburg City Council was formulating a policy to tackle the issue of traffic congestion brought about by the increased use of the motor car as a means of commuting to work. One solution which had great appeal was an underground railway system similar to that of London and Paris.

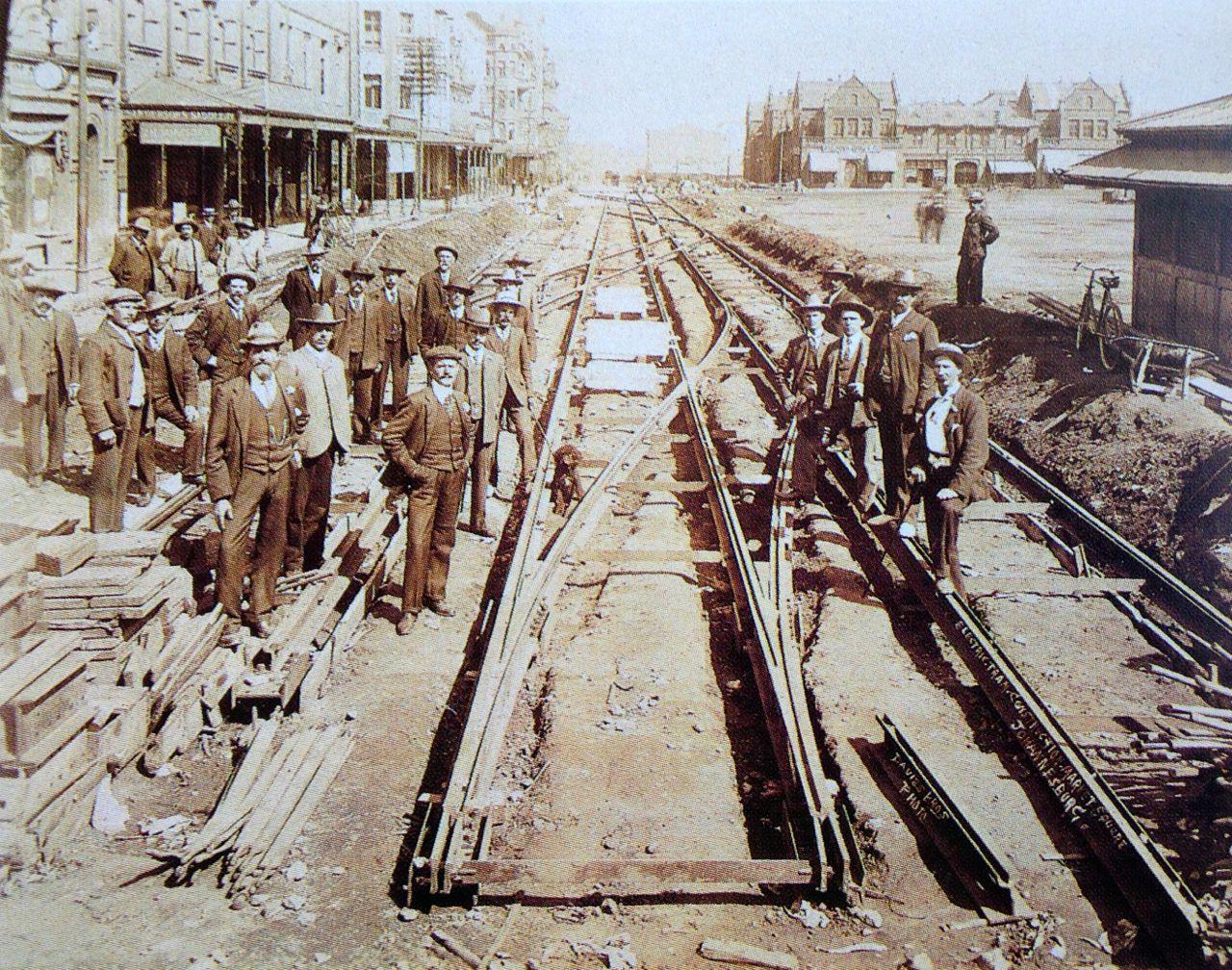

The progress of development of Johannesburg, from the time of the first discovery of gold in mid 1886, was by the establishment of mining villages both east and west of the initial gold strike, along the “Main Reef”. By 1890 Johannesburg and its environs (the “Rand”) had grown enormously and the pressing need for a railway was satisfied by the building of the “Rand Tram”; the name belied the fact that it was a proper railway laid to the Cape Gauge of 3’-6”, for the transport of passengers and goods. The “Rand Tram” ran initially from Johannesburg to Boksburg but was soon extended eastwards to Springs and westwards to Krugersdorp. For shorter journeys around Johannesburg horse drawn trams were introduced in 1891, which were upgraded to electric trams by 1906. Interestingly the tracks of the latter were laid in the road to the Standard Gauge of 4’-8½“.

Tramline being laid in Johannesburg (Source Unknown)

As Johannesburg grew (with its population) it was to extend over a large area, along an east to west axis, with the original villages merging to become its suburbs. The shape of this conurbation was similar to a rugby ball (oval) as the extremities north and south were a shorter distance away from central Johannesburg than the extremities east and west. Up until the early 1960’s the transport situation was adequately handled by trains, buses, trams taxi-cabs and private cars, however it was fully realised at City Hall, that future growth would overwhelm these within a decade or two.

To complicate transport matters the social order of segregation (the Group Areas Act), made black workers stay in townships to the south west of the city on the far side of the mine dumps remote from their place of work The name “Soweto”, an acronym for south-western townships only became official in 1963, when the City Council chose it over other suggestions; one suggestion that did not find favour was Hendrik Verwoerdville!

South African Railways were tasked with providing commuter services from the dormitory towns along the Rand and from Soweto. Johannesburg’s Park Station was modernised in the 1950’s to handle the rush hour rail traffic into the Central Business District (CBD) and two other stations on the southern edge of the city, namely Westgate and Faraday were also brought into operation to handle most of the Soweto traffic. There were no railways going northwards other than the line going to Pretoria via Germiston and Kempton Park, therefore public transport to the northern suburbs was catered for by buses and trolley buses and commuters in private cars had to use Jan Smuts Avenue, Oxford Road or Louis Botha Avenue as the M1 motorway had not yet been completed.

The discourse above sets the scene prior to the great traffic debate of the mid 1970’s, which was over whether or not Johannesburg should have an underground railway in order to reduce the traffic on the roads. The topic may seem trivial in hindsight when at the same time great events were unfolding in South Africa, notably the Soweto Riots of June 16th 1976, which would shake the very foundations of the Apartheid Regime, however at the time it was a most important matter on which hinged the future development of the city centre.

The Star newspaper was actively involved in the debate and stated rather rashly, in late 1977, that the “Jo’burg Underground was On”. Thereafter the pros and cons of the project were actively aired in the press the upshot being that public opinion was in favour of the “Tube” no matter what the cost. Alas the project could not raise the necessary capital to go ahead and was thus shelved.

No tube trains meant that there was no need for stations and no stations meant there was no need for the extra buses that would feed passengers to the stations, this in turn opened the door to the Kombi Taxi industry, which was seen as a cheaper and more flexible alternative to the bus.

Greater Johannesburg still suffers and will continue to suffer from chronic traffic problems. Had the Underground project gone ahead forty years ago by now there would have been extensions to the original lines, mainly running on the surface to the suburbs as they do in London. Indeed a lost opportunity.

To get a glimpse of the thinking behind the Underground scheme one has to backtrack to 1969 when the Johannesburg City Engineers Department had come out strongly in favour of an Underground railway to solve the mass transit problem and defined the advantages of a “Tube” as:

- Frequency and regularity of service.

- No traffic hold-ups, which buses are susceptible to.

- Faster Safer Trips.

- Distribution: the proximity of the tube to major work centres.

- Comfort and ease of travel.

- Capacity of a tube, especially in peak hours.

- Relief of road traffic density.

- Flexibility of providing “park and ride”, “kiss and ride” and “bus and ride” services.

Furthermore the City Engineer initiated a feasibility study that was carried out by London Transport (the experts), which proposed a 24 km long “Metro” with an estimated cost of R151 million should work start before the end of 1971. The cost was based on three routes converging on a central interchange station. The northern route would be the longest with a length 13 km terminating near to the Houghton Golf Course at one end and Parkview Golf Course at the other, thus forming a U-shape. The southern route would run for 7.6 km from Rosettenville Corner to town and then turn west to continue to Mayfair. The eastern route would be 3.4 km long and run to Bertrams and Jeppe. No immediate action was taken on the feasibility study and it was held in abeyance until it was finally shelved.

A landmark report was published in 1975 concerning urban transport in South Africa’s major cities; it was the “Driessen Report” and it summarised the pros and cons of an underground railway system as follows:

FOR

- Valuable ground space could be saved.

- “If traffic is dense enough the downtown end of the underground can be adapted to cater for a substantial portion of city distribution needs”.

- In the event of another fuel crisis an electrically powered railway system would become a more attractive proposition (than a fleet of diesel consuming buses).

AGAINST

- Huge capital costs, particularly of tunnelling, construction of stations and provision of lighting and ventilation.

- Difficulty of changing routes.

- Possible “social” effects, i.e. the taking into account of South Africa’s complex racial structure.

Nearly all arguments against an Underground (anywhere in the world) boil down to the same thing and that is money. Johannesburg did not have the financial resources to build a “Tube” itself which meant it had to go “cap in hand” to the Government, which at the time had other priorities to deal with (the SADF in Namibia and Angola) and thus money was not made available.

Johannesburg’s flirtation with the idea of its own Underground was over by the mid 1980’s, however that was not the end of story as 30 years on we now have an Underground that runs from Park station to Sandton via Rosebank, which is part of the rapid transit railway line between Johannesburg and Pretoria, known as the “Gautrain”.

References and further reading

- “Like it Was – “The Star” 100 years in Johannesburg”.

- “A City Divided – Johannesburg and Soweto” by Nigel Mandy.

- “Johannesburg Tramways” by Tony Spit & Brian Patton.

- White Paper on the Report of the Committee of Inquiry into Urban Transport Facilities in the Republic, better known as the “Driessen Report”.

- “An Underground Railway for Johannesburg” Parts 1-4 from “RAILWAYS Southern Africa”, issues for August, September & December 1977.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.