Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The March 2022 wedding reception of my niece at the Kalmoesfontein Wine Farm near Riebeek Kasteel provided us with the excuse for a meandering road trip through the Cape.

En route to Hanover, we diverted to the civilian cemetery at Springfontein where I hoped to locate the grave of Constable Jury Johannes Geldenhuis killed during the 1922 Rand Revolt.

Springfontein Cemetery. The grave of Constable Geldenhuis may be towards the rear. (SJ de Klerk)

Colonel RS Godley in his memoirs Khaki and Blue, recalled Constable Geldenhuis cantering his horse down the Brixton Ridge on Friday 10 March 1922 to buy some bread at the nearest shop, when a striker on the veranda of an adjacent house shot and killed him. Initially buried in the temporary burial ground at Milner Park, his remains were seemingly later reinterred in Springfontein, where he and his wife lived. It seemed appropriate to visit his long forgotten grave, almost 100 years later to the day of his death. But after the recent country wide summer rains, the older precinct of this little cemetery was rather overgrown, and I was unable to locate it.

Travelling through the Karoo, the sight of a little hamlet such as Hanover remains a welcome one with the beckoning tower of the Dutch Reformed Church, abundant bird life, shady Oak, Acacia, Cypress and Pine trees, inviting the weary traveller.

Hanover was established on the farm Petrusvlei of Gert Gous. It was named Hanover to commemorate one of his ancestors who came from Hannover in Germany.

White farmers moved into the Karoo early in the eighteenth century and within a mere hundred years the first villages were established to serve as religious and administrative centres. Beaufort West was established in 1818, followed by Colesberg in 1830, Richmond in 1844, Middelburg in 1852 and Hanover in 1854.

For a while during the 1870s, Hanover had been on the direct route of one of the stagecoach lines carrying passengers between Cape Town and Colesberg. Following the discovery of diamonds at New Rush and Colesberg Koppie, later named Kimberley, Hanover attracted passing businessmen, diggers and ‘smouse’, all seeking their fortunes on the diamond fields.

In 1876, the village’s first magistrate Charles Richard Beere, arranged for convicts to lay out a stepped footpath to the top of Trappieskop and encouraged the planting of trees.

Historically, the main Richmond – Colesberg road entered the village along Market Street, and it was on this avenue that the Market Square, various trading stores and the two hotels were located. But like so many other smaller towns, the construction of the National Roads in the 1970’s that skirted them, brought mixed blessings. While relieving Hanover of excess road traffic, they sadly also did the same for local business. The two entrance roads now positioned at right angles to the N1, appear rather uninviting, and fail to do justice to this historic village.

The village itself consists of three parts; old Hanover where most inhabitants are White and Afrikaans speaking, Joe Slovo, a mainly Afrikaans speaking Coloured community and Kwezi, a mainly Xhosa community.

The low hills shielding Hanover from the westerly winds also provided the perfect viewpoints for photographers to record local life and so Hanover became the most photographed village in the Great Karoo.

After booking in at the Boutique Guesthouse in Darling Street we strolled around the village to relieve our cramped ligaments.

Our first stop was at the imposing Dutch Reformed Church designed by William Henry Ford, with its cornerstone laid in 1906. See main photo.

It replaced the original church, a typical Cape Dutch ‘kruiskerk’ (cross church), when it became too small to house the congregation, which in the first half of the 20th century is said to have totalled almost seven hundred parishioners.

Author Hans Fransen described the existing church as follows: ‘A cruciform building, plastered with corners and other trimmings in granite (the reverse of the usual recipe of stone with plaster trimmings), in an amazingly contemporary uncluttered style’.

Impressive pulpit of the Hanover DR Church, able to accommodate 12 people. Note the seat built into the front of the pulpit for the lead vocalist. (SJ de Klerk)

William Henry Ford (1868 - 1921) designed fourteen of South Africa’s most impressive Dutch Reformed Churches in the Gothic style. Born in Melbourne, Australia, he qualified as an architect at the University of Victoria. During the South African War, he emigrated to South Africa, probably in the expectation that considerable reconstruction work would follow the devastation brought about by the war.

The Hanover Church was his first ecclesiastical building in South Africa and although a very successful one, he may be better known for designing the beautiful Dutch Reformed Mother Church (1912) that graces the appropriately named Church Street in Kroonstad.

Other of his fine churches are to be found in Ventersburg, Dealesville, Thaba Nchu, Frankfort, Barkley East, Burgersdorp, Sterkstroom, Jamestown, Aurora, Heidelberg (W. Cape), Benoni, and Vosburg.

Cambedoo House at no. 3 Viljoen Street, immediately west of the church, and now the town museum, is interesting. Set at an angle to the street it might predate the town and could have been the original Petrusvlei farmhouse. T-shaped and the only house of such a plan in the town, it was probably refashioned circa 1860, as a townhouse.

No. 3 Viljoen Street, now the Hanover Museum may predate the town. (SJ de Klerk)

South of Church Square, two attractive Victorian Karoo houses complement the church. The water furrow runs between the trees and the house, (SJ de Klerk)

From the Church Square we strolled along Murray Street towards the Market Square, then turned west into Market Street past the historic CJV Hall. The abbreviation CJV stands for ‘Christelike Jongeliedenvereniging’ (Young Men’s Christian Society). The CJV was an initiative of the Dutch Reformed Church and established in Pretoria in 1883. It gradually expanded throughout the country in the late 19th and early 20th century. The society held meetings, debates, played music and performed plays and played a significant role in the promotion of Afrikaans language and culture in the rural areas following the South African War.

This Hall, with its simplified ‘Cape Gothic’ appearance is like many other 19th century churches, found in the Cape.

CJV Hall consecrated in 1896 (SJ de Klerk)

A beautifully engraved and well-preserved sandstone corner stone adorns this Hall (SJ de Klerk)

Since we were now in the Karoo where iconic South African author Olive Schreiner (1855 – 1920) spent several years, I wondered why her association with Hanover is not better promoted. Olive, later joined by her husband Samuel Cron Cronwright lived in Hanover from 1900 to 1907, making it the village in South Africa where she lived for the longest period of her adult life. She met her future husband Cron Cronwright (1863 – 1936) when he was the manager of the farm Krantzplaats (now Lime Bank) on the banks of the Fish River between Middelburg and Cradock. In 1894 when she was almost 39 and he had just turned 31, they were married at the Middelburg Magistrate’s Court. I was therefore keen to point out to Lorraine, the little Karoo building where Cron Cronwright-Schreiner had his office as a so-called enrolled agent and the other two houses where they are known to have lived while in Hanover.

Office of ‘enrolled agent’ Samuel Cron Cronwright-Schreiner (SJ de Klerk)

Appearing much as it would have in Cron’s day, the rear additions are from a later period and so too is the entrance to what would have been a typical Karoo bullnosed roofed veranda. Regrettably, the veranda roof damaged in a storm some years ago, has been dismantled.

Cron Cronwright joined Olive Schreiner in Hanover in August 1901 and since he could not obtain a permit to leave Hanover during wartime, he gave up all hope of completing his legal articles. But with the knowledge gained through his ten months’ work in attorneys’ offices in Johannesburg, he set himself up as an enrolled agent, later branching out as an Estate Agent, Auctioneer, Sworn Appraiser, and Life and Fire Insurance Agent, and gradually built up a successful practice in the district. Initially he set up an office in the CJV Hall, but almost immediately relocated to this building in Loop Street, facing onto the Market Square and the parsonage, which was more convenient for his purposes.

Retracing our steps, we turned south into Rawstorne Street, the western boundary of the village. Here a pathway leads to the top of the Trappieskop, providing a lovely view over the village. Since it was still hot, we elected to ascend this hillock later in the day when the Karoo afternoon heat would have abated somewhat.

Typical Victorian Karoo house. Pine and Cypress trees on the pavement with Trappieskop and memorial to Magistrate Richard Beere to the rear. (SJ de Klerk)

We were hoping to see flocks of the Lesser Kestrels (Falco naumanni or Klein Rooivalkie in Afrikaans) roosting in the many large trees along this street. Migrants from Europe and Asia they do not breed here but arrive in late October and depart the first week of March. Unfortunately, it seemed that we had arrived just a few days too late in the season. On a previous December visit to Hanover, I was fortunate to see hundreds of them darting around.

The N1 now separates the historic walled cemetery from the village. Here our attention was immediately drawn to the pyramid shaped memorial; the communal grave of Charel and Jan P. Nienaber and Jan A. Nieuwoudt, bywoners on the farm De Bad in the district. The three of them were sentenced to death by Military Court in De Aar and executed there by firing squad in March 1901 for allegedly participating in a train derailment at Taaibosch, some 20 kilometers west of the Hanover Road station on the Noupoort railway line.

By April 1900, the British military had taken over the administration of justice from the Cape Courts and begun to impose death sentences on captured Boers or rebels found guilty of offences such as sniping, train wrecking or murder. During the war some 44 Burghers and/or Cape Rebels were sentenced to death by military courts and executed in the Cape Colony. Several of these executions took place in the nearby towns of De Aar, Middelburg and Colesberg. Olive was convinced that the principal witness, who had turned state witness was lying. Later when Cronwright was elected to parliament, he managed to have their executions reviewed and the widow of Nieuwoudt recommended for a pension. Olive and Cron also arranged for their remains at De Aar to be exhumed and reinterred in Hanover. The ominous quotation from Romans Chapter 12 Verse 19 appears below their epitaph, ‘Vengeance is mine; I will repay, saith the Lord’.

Communal grave of Charel and Jan Nienaber, as well as Jan Nieuwoudt. (SJ de Klerk)

Nearby is the grave of Sergeant Charles Leach of Nesbitt’s Horse who died of wounds received at Spytfontein near Hanover on 20 June 1901 (SJ de Klerk)

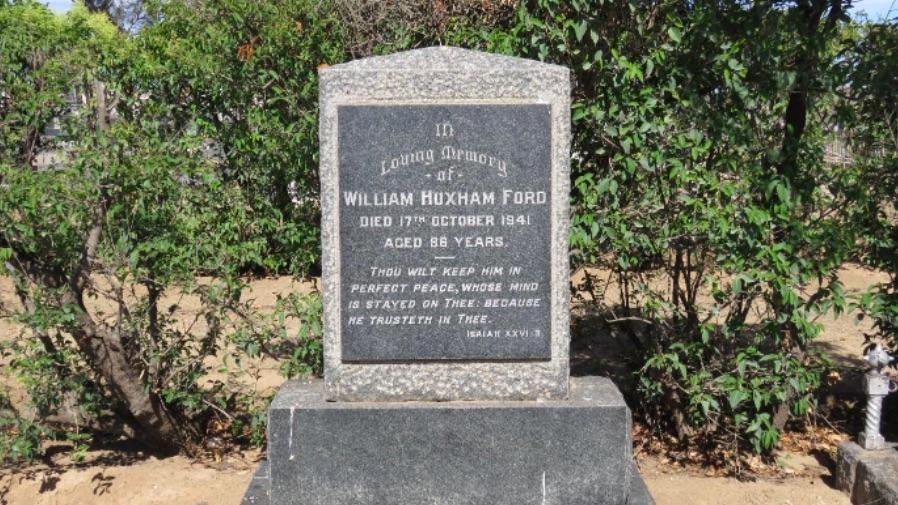

Another tombstone with a connection to Olive Schreiner is that of William Huxley Ford (not to be confused with architect William Henry Ford), sometime proprietor of the Royal Hotel, where Olive Schreiner boarded, upon her arrival in Hanover in 1901.

Tombstone of William Huxley Ford, proprietor of the Royal Hotel, where Olive Schreiner boarded shortly after arrival in Hanover (SJ de Klerk)

Back at the corner of Market and Rawstorne Streets, we ascended Trappieskop to enjoy the sun setting over the village.

Hanover would make a very suitable venue for some enterprising soul to set up an amateur observatory to offer star gazing from one of the surrounding koppies in the clear Karoo skies.

In 1908, Harvard Observatory sent a team to South Africa to investigate the erection of a station to observe parts of the sky around the southern celestial pole, which could not be observed from the northern hemisphere. Harvard Observatory had already established a similar station at Arequipa in Peru, but since the cloudy season from December to March impeded celestial observation, consideration was given to moving the observatory elsewhere in the southern hemisphere.

The excellent climatic conditions of South Africa were well known and had already been brought to the attention of the Director of Harvard Observatory by Sir David Gill. Accordingly, the expedition sent here was tasked to investigate the possibilities.

Although Hanover was initially recommended as a suitable site for the installation of a southern hemisphere observatory, Bloemfontein was ultimately selected and the telescopes and other equipment at Arequipa dismantled and transferred to what would become the Boyden Observatory at Mazelspoort, where observing work commenced in September 1927.

The following morning after a sumptuous Karoo breakfast, we explored the eastern part of the village, before departure. Walking east along Market Street we passed several interesting buildings, but the Art Deco styled Hanover Hotel Lodge impressed us.

Hanover Lodge Hotel in the Art Deco style. The Palm trees and green walls contrasted with the white pillars, evoke aspects of Miami, Mecca of Art Deco hotels. (SJ de Klerk)

One does not normally associate the Karoo with modernist architecture; Brakdak, Victorian, Edwardian and Karoo Vernacular definitely, but not Art Deco. Still the Little and Great Karoo will surprise you with attractive Art Deco hotels and buildings in villages such as Montagu, Prince Albert, Hanover, Colesberg, Victoria West and Britstown.

In Church Street we passed the Court House dating from 1897. Note the high roof of the Court Room and the covered verandas, that would keep the interior cool.

Court House, Hanover 1897 (SJ de Klerk)

The Court building in Middelburg where Olive Schreiner and Cron Cronwright were married in 1894 has been demolished but would have been like the one above.

Nearby we were pleased to encounter St Anne’s Anglican Chapel dating from 1895 - 96. The little rectangular chapel with walls constructed of stone, plastered, white-washed and with paired lancet windows appeared very attractive, but the wooden bell housing clearly requires some urgent repairs. Sadly, like many other churches, this chapel is now only used for occasional services, with the Rector based in Middelburg.

St Anne’s Anglican chapel (SJ de Klerk)

Decorative door hinge from St Anne’s Anglican chapel (SJ de Klerk)

Almost directly behind this chapel but two or three streets to the north, we caught glimpses of the two Schreiner dwellings.

Karel Schoeman in his biography of Olive Schreiner in Hanover during the South African War, Only an Anguish to Live Here, beautifully captured her stay in this remote little village during the war years. Her joy upon arrival here soon turned into despair as the martial law regulations prohibited her from wandering around the village and the little koppies beyond the town’s boundaries. Some years later Olive gave a dramatic, if exaggerated description of this period of her life, ‘I was living in a little house on the outskirts of the village, in a single room, with a stretcher and two packing-cases as furniture, with only my little dog for company. Thirty-six armed African natives were set to guard night and day at the doors and windows of the house; and I was only allowed to go out during certain hours in the middle of the day to fetch water from the middle of the village, or to buy what I needed. I was allowed to receive no newspapers or magazines.’

When the war ended the Cronwright-Schreiners first moved into a house near the church, that she called ‘the oldest house in town but one’, but it proved rather damp, hence they moved to what Olive described as a ‘dear tiny house, a doll’s house’, probably the one illustrated below, in Burger Street.

North-western perspective of the Schreiner cottage in Burger Street. (SJ de Klerk)

Subsequently Cron purchased some plots of land behind this cottage on which he built a spacious but rectangular house of unplastered brick consisting of three interleading rooms, in what is now Grace Street. The covered veranda is a later addition.

Schreiner house in Grace Street, almost directly south of the Schreiner cottage (SJ de Klerk)

In 1907 the Cronwright-Schreiners waved goodbye to Hanover and moved to De Aar where the house they lived in is still extant.

We were also about to depart Hanover for Nieu Bethesda where the Owl House and the joint creations of enigmatic outsider artist Helen Martins and craftsman Koos Malgas beckoned.

Main image: Dutch Reformed Church at Hanover with Dassieskop to the left rear (SJ de Klerk)

About the author: SJ De Klerk held many senior positions in HR during a distinguished career in the private sector. Since retiring he has dedicated time and resources to researching, exploring and writing about South African history.

Sources

- Christelike Jongeliedenvereniging see Encyclopaedia of SA Theatre, Film, Media and Performance @esat.sun.ac.za

- First R & Stott A. Olive Schreiner. A Biography. Andre Deutsch. 1980.

- Fransen H. Old Towns and Villages of the Cape. Jonathan Ball Publishers. 2006.

- Godley RS. Khaki and Blue. Lovat Dickson & Thompson Ltd. 1935.

- Hanover 2013. A Study in Conservation. University of the Free State, Department of Architecture. 2014.

- Hobman DL. Olive Schreiner. Her Friends and Times. Watts & Co. 1955.

- Hoevers J. Geskiedkundige Kerke. ʼn Gids tot 50 Tradisionele Kerke. Kontak. 2012.

- Jarrett AH. Boyden Observatory (A Concise History) in Acta Academica Nr. 12 1973.

- Jooste G. & Oosthuizen A. So Het Hulle Gesterf. JP van der Walt. 2000.

- McLachlan GR & Liverside R. Roberts Birds of South Africa. Struik. 1978.

- Menache P. & Wolff H. Die NG Kerk. Ons Erfenis. ʼn Fotoversameling van die Argitektoniese Skatte van 139 NG Kerke in SA. 2021.

- Nienaber PJ. Suid-Afrikaanse Pleknaam-woordeboek. Tafelberg Publishers. 1972.

- Schoeman K. Only an Agony to Live Here. Olive Schreiner and the Anglo-Boer War 1899 – 1902. Human & Rousseau. 1992.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.