Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

We are honoured to publish this in depth article by Dr Robin Lee on the history of radar in the Overstrand area during World War II. Robin is a retired academic and founder member of the Hermanus History Society which is dedicated to the identification and preservation of heritage sites in the area.

At the beginning of World War II British anti-aircraft guns struggled to bring down even one aircraft each day in the waves of German bombers pounding their cities. In 1940 it was calculated that the gunners, using conventional metal sights on their guns, had such difficulty in hitting their targets that, on average, 75 000 shells were fired to bring down a single enemy bomber. Each shell contained valuable material that could not be retrieved for use again and manufacturing the shells took the time of hundreds of workers, mainly women.

However, by 1943, aided by a new technology, gunners were expending an average of only 2 000 shells per plane downed. By 1945 this number had dropped into the hundreds. The new technology was RAdio Detection and Ranging, known to everyone as RADAR. It was also very effective in detecting ships and submarines (near or on the surface) and later in the war, became an offensive weapon, when it was mounted on aircraft or ships to focus firepower on targets.

Painting: flak bursting around bombers

Historians love to play the game of “What really won the war?” and for World War II answers range from the Secret Service hoax of ‘the man who never was’; to the decoding of German military messages by Alan Turing and colleagues at Bletchley Park; to Robert Oppenheimer and the Manhattan Project developing the atomic bomb. But there is a case that radar was really the technology that won the war for the Allies.

And radar had a specific connection with a part of what is now the Overstrand Local Municipality. Between 1942 and 1945 three ‘radar stations’ (as they were known) were built in the western part of the Overstrand, two on Cape Hangklip itself and one in Betty’s Bay. This is their story and it is another link between the residents of the Overstrand and the history of South Africa.

What is radar and how was it used?

The basic components of radar are a transmitter, a radar antenna operating as a receiver, a signals processor and a display screen. The transmitter generates short pulses of radio waves (known as signals) and transmits theses in a narrow beam. When the beam encounters an object such as a ship or aircraft the radio waves in the narrow beam are scattered. However, a small fraction of the original waves is scattered back in the direction of the transmitter, which collects the waves and sends the resulting current to the radar receivers. The receivers amplify and detect the signals and send the results to the signals processor which extracts the desired information (distance, height and speed of object) and provides this information to the radar display screen where it appears as a ‘blip’ of light.

The distance to the object is determined by the time the wave takes to return to the radar. The direction to the object is given by the position of the antenna when the returned signal is detected.

Captain (later Major and Professor) G R Bozzoli is credited with building the first South African working radar equipment in 1939. In a lecture in 1982 he defined radar as follows:

Radar is the name… of the well-known system of locating the position of a ship, aircraft or other object by measuring the time delay between the instant of emission of a pulse of radio frequency electromagnetic energy, and the instant of arrival of that same pulse reflected from that ship or aircraft…

Dr. F J Hewitt, also involved in the earliest days in South Africa, wrote in 1975:

I regard radar as a system for indicating the presence and position of an object by means of the scattering or echoing of radio waves by that object. Radar involves the measurement of the time the radio waves take to travel from their origin to the scattering object, and back. This time element is vital in the definition of radar. By knowing the travel time and the speed of travel of the waves, the range can be determined.

Geoffrey Mangin and Sheilah Lloyd, who both served in the Special Signal Services, in a paper written in 1975, define radar as:

…beaming brief, powerful radio pulses in a specific direction. Upon striking an object, these pulses are reflected back to register as ‘echoes’ or ‘blips ‘on a television-type screen. The time taken by the radio pulses to return indicates the distance of the object.

The South African players

Several prominent South Africans feature in the story of radar in this country. The most visible was General Jan Christiaan Smuts, who, on 4 September 1939, defeated the Nationalist Party of Barry Hertzog on a vote in Parliament that took South Africa into World War II on the side of the Allies.

Smuts at the San Francisco Conference in 1945 (Smuts House)

Almost immediately, the British Government invited South Africa to send a representative – preferably a physicist - to London to be informed about a secret weapon being developed. By the end of September Smuts had selected Dr. Basil Schonland, then the Director of the Bernard Price Institute for Geophysical Research at Wits University.

However, Schonland never went to London, but acquired the knowledge in another way, as we will see as the story unfolds.

Sir Basil Schonland, as he later became, was born in Grahamstown in 1896, matriculated at the age of twelve and studied physics at Rhodes University. At the age of 18 he volunteered to serve in World War I and made a distinguished contribution in the Signals Corps, for which he was awarded an OBE. After working at the famous Cavendish Laboratories at Cambridge University, he returned to South Africa at the request of General Smuts and joined the faculty at UCT, soon becoming Professor of Physics. His speciality was electrical discharges of lightning strikes and in 1937 he moved to the Transvaal to head up the Bernard Price Institute for Geophysics. Obviously the Highveld provided many more opportunities to observe lightning strikes than Cape Town. He joined the army again in 1939 and, with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, started the South African Special Signals Services, which he commanded until 1941.

Once appointed by Smuts, Schonland rapidly assembled a team of young men that comprised:

- Staff Sergeant C J Anderson (technician)

- Captain G R (Boz) Bozzoli (then a senior lecturer in Electrical Engineering at the University of the Witwatersrand and later Vice Chancellor of that University)

- Captain P G Gane (Senior Research Officer at the Bernard Price Institute at Wits University)

- Captain F J Hewitt (Research Officer at the BPI)

- Major D B Hodges (Professor of Physics at the University of Natal) Staff Sergeant

- J A Keiller (instrument maker)

- Captain W F Phillips (Senior lecturer in Physics, Wits University)

- Captain N H Roberts (Senior lecturer in Physics, University of Cape Town)

- Staff Sergeant A V Scheferman (technical support)

- Captain (Mrs.) S Schonland (Confidential Records Secretary)

Several of the original members went on to distinguished careers in South Africa and abroad, but the scope of this Report does not allow us to follow them.

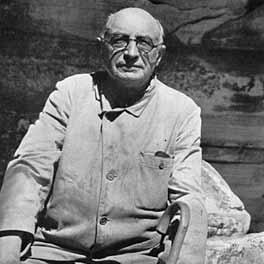

Sir Basil Schonland (South African Military History Society)

The South African Special Signals Services

The Special Signals Services was seen as a top secret unit in the War effort and, according to Peter Brain, the author of a book length history of the unit, no documentation exists to confirm the actual date of its establishment. However, this took place probably in late 1939 or early 1940. Such was the level of secrecy that, in May 1940, when it was deemed fit to test the early radar sets over water, the unit was sent to Durban, but the officer in charge could not tell even the second in command what the convoy of trucks contained and where it was going. Everyone assigned to the SSS was administered an oath of secrecy. Because, perhaps, of the aura of secrecy created around it, the SSS was frequently given derogatory names. In the regular army the SSS was frequently called “Soldate Sonder Sense”, while the strategy of appointing only university educated women as radar operators earned them the nickname “Super Snob Squad”. A third nickname was “Secret Solemn Society”.

Mangin and Lloyd succinctly describe the objectives of the Special Signal Services:

With the Suez Canal closed (the Cape) was a very busy strategic shipping route – as the enemy was well aware! The object of the radar coverage was the detection and tracking of all aircraft, ships, small surface craft and surfaced submarines. This also facilitated another useful service: warning friendly shipping against running aground in poor weather and at night, with no lighthouses functioning and an enforced ‘wireless silence’. Especially ships unfamiliar with the coast and with inadequate charts. It is said that at least one ship was ‘navigating’ with a school atlas!

The SSS was judged to be very successful and, December 1944, when it was fully staffed, it comprised 1621 personnel in total, of which officers totalled 145 (117 males and 28 females) and other ranks totalled 1476 (of which males totalled 969 and females 507).

Active service: ‘the clever boys’

As mentioned above, Schonland did not go to London for the initial briefing on radar. Instead, it was arranged that Sir Ernest Marsden (who had represented New Zealand at the talks) would meet with Schonland on board the ship on which he was returning home when it docked in Cape Town.

Sir Ernest Marsden in 1921 (British & Irish Physicists & Mathematicians on Pinterest)

Marsden and Schonland would travel together to Durban and the briefing would take place during the trip. We are dealing with two of the most intelligent men of their time so this hastily-concocted plan actually worked. While the exchange of information was taking place, Schonland observed Marsden consulting a manual from time to time, so asked if he could borrow it to study. He then went ashore and had the manual copied onto glass plates that could be duplicated by a friend at the University of Natal in Durban. Bozzoli later described this material as ‘virtually unreadable documents (that) were the only technical papers available.’

With this resource the South African team produced its own operational radar within three months. Parts were bought from amateur radio parts suppliers and, if not available, manufactured by members of the team. The first successful trial of South African radar took place from the Wits campus on 16 December (then known as Dingaan’s Day) 1939, when an echo was returned from the Northcliff Water Tower, 8 kms away.

Northcliff Hill (Rod Kruger)

In 1982, Bozzoli recalled that he and Schonland ‘liked to remember that exciting day of 16 December 1939. I occasionally sent him a telegram on subsequent Dingaan’s Days, to remind him of what I believed we had achieved. The last reply I had from him was instant and typical. It simply said: “Thanks. Weren’t we clever boys?”

Later in December 1939 the range was extended to the Magaliesberg Mountains (100kms away) and, early in 1940, an aircraft was detected in flight. During the first run of this test, the aircraft disappeared ‘off the radar’ for a short time. This was not a failure of the radar. It turned out that the pilot had deviated from the prescribed course in order to wave to his girlfriend in her garden in Roodepoort.

Schonland’s team upgraded the equipment all the time and put much effort into recruiting and training operators and technicians. In late 1940 a South African radar operations group was sent to East Africa to support South African and British troops in action against the Italians. The group played a positive role there, and also in the Middle East, but in 1941 the Royal Air Force arrived to install its own radar and the South Africans returned to base in their own country. Attention now focussed on the use of radar to detect naval movements around the South African coast. The first step was to establish a radar station in Cape Town.

South African developments

Setting up the first radar station was not without its problems. In an article published in 1998 entitled “The Special Signal Services (SSS): We Scanned the Seas and Skies in the Second World War” Geoffrey Mangin and Sheilah Lloyd describe the events thus:

On 14 May 1941 Major 'Boz' Bozzoli, Lieutenant Eric Boden and Staff Sergeant Scheferman left Johannesburg with two heavy vehicles containing equipment to set up a twin mobile radar set on Signal Hill in Cape Town. Not surprisingly, the problems they encountered in Cape Town after that slow five-day journey were daunting: Maj Bozzoli found that the Army knew nothing about them and that no accommodation, rations or, more importantly, helpers had been arranged. Eventually, four men were supplied to help, but they were unfortunately all classified C3 - unfit for active service. One man had a broken arm, another a chronic chest disorder, the third an awful skin disease and the fourth was suffering from pneumonia! Since these men could not be expected to provide assistance with the heavy digging and other necessary hard labour required, the major, lieutenant and staff sergeant set to work in atrocious weather conditions. Finally, the station was installed and operational. Naval personnel at the adjacent Port War Signal Station helped with rations and accommodation. Maj Bozzoli managed to obtain a more useful group as operators and the set went on the air with Lt Boden as its first commander. Good results were obtained immediately, when shipping was detected at about 30 km, but a violent storm demolished the aerials and a further four days were spent in repairing the damage. Thereafter things settled down and all went well.

Mobile radar Signal Hill 1940 (South African Military History Society)

Despite this inauspicious beginning, within a year, twelve radar stations with South African equipment were operational in the vicinities of Cape Town, Port Elizabeth, East London and Durban. Secrecy was regarded as paramount, especially in a country where elements of the population openly sided with the Germans, so the installations were known as UDES (Union Defence Experimental Stations).

Each station required 10 operators and 4 technicians to maintain a 24-hour continuous surveillance and radar training schools were set up in Johannesburg, Cape Town and Durban. There were various administrative and service personnel at each station and, because of relative isolation, each station constituted a small community of its own. After basic training the recruits were allocated either to a regional command centre, known as a “Freddie”, in the cities of Cape Town, Port Elizabeth and Durban or to one of the operating stations. Mangin and Lloyd describe the options:

Much discussion took place as to whether it was better to be posted to a station or to 'Freddie' - not that they were given a choice! Those working in 'Freddie' had an overall picture of what was happening throughout the region, whilst those at a station knew only what was showing up on their own screen. 'Freddie' girls, by working fairly closely with Combined Ops, were often privy to secret information about ship sinkings and tonnages, the detection of U-boats, aircraft losses, etc. Such information, being totally secret, only reached the stations long afterwards, if ever. 'Freddie' girls also had all the city amenities to draw upon during their hours of leave, whilst station operators usually lived at isolated outposts in an unspoiled environment, with sea and empty beaches on their doorstep.

Because as many men as possible were being drafted for active service and those not fit for service certainly could not work effectively on a radar station, in 1941 it was agreed to recruit women with a university education as radar operators. This decision gave a particular direction to the histories of the various radar stations. In due course there were 15 radar stations in the Western Cape alone, tracking more than 500 targets at any one time. The stations were at: Noordbaanhoek (Saldanha), Yserfontein, Somersveld (Darling), Melkbosch, Blaauwberg, ‘Windy Ridge’ (Robben Island), Signal Hill, Fort Collins (Hout Hay), Slangkop (Kommetjie), Rooikrans (Cape Point), Hangklip, Silversands (Sandown Bay, now Kleinmond) and Betty’s Bay. In addition, in Cape Town, there was the ‘filter room’ to which all information about movements of targets was sent and integrated into an overall picture of movements of shipping around the Cape.

Yserfontein radar 1940 (Yserfontein.net)

Plotting courses at Yserfontein (Yserfontein.net)

Each station consisted of the radar room in which the operators worked, the radar installation itself, technical workshop facilities, well-separated accommodation for men (usually technicians) and women (operators), but with communal dining and leisure facilities. At Silversands, near Kleinmond, the split-pole fence separating the men’s and women’s accommodation was known as the ‘chastity fence’. The operators worked in pairs, taking 5 hour shifts. One operator tracked and marked the plots on a map of the area and the other read movement off the screen of the radar and telephoned information to “Freddie”. Security measures depended on the location of the radar station, but were not always a major concern. At Silversands the station was fenced, with a single gate, which was “guarded day and night by members of the Native Military Corps, armed with assegais. No one without the proper pass and password could get near the tech hut, but it is difficult to imagine how the assegais would have repelled a U-boat raiding party after the station’s secrets.”

The traditional structures of the military had difficulty in incorporating the SSS. This was exacerbated by the secrecy that was kept around the activities of the SSS, leading to much red tape and some humorous incidents, as described by Bozzoli:

Because of the great secrecy attached to everything we did, GHQ (Group Headquarters) agreed to allow us …to buy all our technical needs on a special order book, which was not open to inspection by the normal auditors. Instead, our accounts were sent over privately to Pretoria for safe-keeping and auditing after the war. However, a zealous high-up government servant thought he should know what was going on, and began going through the shoals of order counterfoils. He found valves, resistors, capacitors, transformers, copper, brass and steel screws, nuts and bolts…all of which meant little to him…He did gib a little when he came across “tents, officers, for the use of.” “Hardly secret”, he thought and made a note to query this. He did, too! But what sent him through the roof…was an order signed by Mrs. Hartshorne. She had decided that the army issue was too rough for her girls at Mouille Point and had ordered 200 extra-soft toilet rolls.

Hangklip, Silversands and Betty’s Bay

The stations we are most concerned with were established at roughly the same time during the war. Hangklip and Silversands were established in late 1942 and mid 1943 respectively, while Betty’s Bay was opened late in 1943. Hangklip’s technical hut was built as high up the mountain face as possible, to ensure a wide coverage.

Cape Hangklip Tech Hut 1

There was no space for the power plant (generator) next to the hut so it was positioned about 200 metres lower down the slope, adjacent to the accommodation at Silversands. This caused considerable problems. Operators had to climb a steep and rough path to the hut in all weathers and, as no telephone could be installed, communication had to go by radio via the “Freddie” in Cape Town. The station at Silversands focused on long range sea and air cover, while the main radar at Hangklip dealt with sea traffic within a short distance of the coast.

Betty’s Bay was regarded as a land station and was designed to track aircraft, detecting them as far away as 200kms.

All three stations were regarded as remote from an urban settlement. Sheilah Lloyd has left a telling description of the difficulties of reaching the stations:

To reach it, [I] had to travel by train from Cape Town to Somerset West and climb into the back of the 'ration van' (which collected supplies every few days and was the station's link with civilization) and set off along the coast road. At Steenbras Bridge, which was securely guarded, military passes were checked and from there on, the van drove on an untarred road for some 40 km through unspoiled wilderness. On one side was the mountain and flowering fynbos; on the other the sea. A strong clean wind blew the scents of sea and mountain around those at the station - and there was never another human habitation in sight.

Clarence Drive, which is now the tourist-friendly, scenic route from Gordon’s Bay to Betty’s Bay, was under construction at this time. The story of how it was conceived, how it was built largely with the unpaid labour of Italian prisoners of war is worth a report of its own. The barracks used by the POWs are incorporated into the Glen Craig

Training Centre.

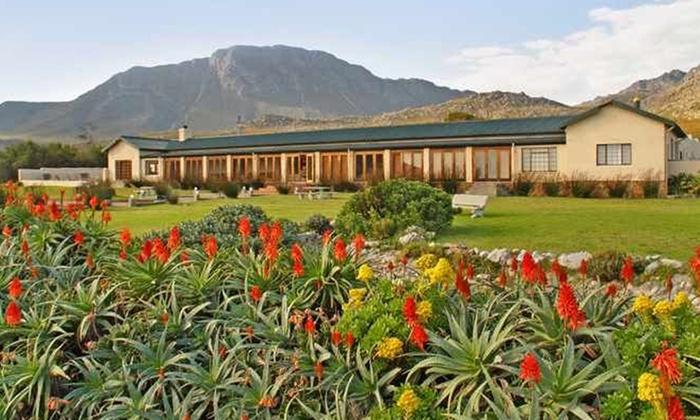

Glen Craig Training Centre (glencraig.co.za)

The radar at Hangklip was operated by men, with women working at the site at Silversands and, later, Betty’s Bay. Women went on shifts of five hours each in pairs. One operator watched the screen and telephoned tracking information to the Freddie in Cape Town. The other maintained contact with the ‘tracks’ within the area covered by her radar. Though the work was later described by a male officer as ‘tiring’ and ‘boring’ the volume of information handled was large. Sheilah Lloyd quotes an official document that records that the South West Cape division handled the tracking of nearly 1100 potential targets in a week, involving the plotting of movements that were recorded by 10 477 ‘arrows’, each of which had to be moved as the position of the track changed. Sheilah Lloyd served as a radar operator at Somersveld near Darling and at Hangklip and Silversands. After the War, she wrote personal accounts of life at both sites. Here is an extract from her description of Silversands:

The nearest thing to civilization for those at Silversands was Sandown Bay (now known as Kleinmond). Situated at the mouth of the lovely Palmiet River quite some distance away, it boasted a typical old-fashioned South African hotel, a few houses, a general dealer-cum-bottle-store and a manual petrol pump. The garbage from the camp had to be taken to Sandown Bay once or twice a week for disposal and the girls, if not on shift, were allowed to go along for the ride. In the 'ladies lounge' of the Sandown Hotel they were served the beverage of their choice. Port and lemon was a favourite, and reasonably daring, whilst ginger squares (ginger brandy and ginger ale) were also popular. Very occasionally there would be a dance at the hotel on a Saturday night, well attended by the local community from far and wide - and every now and again the girls were permitted to join them. Those were the dancing years and long dresses were the essential wear and Glen Craig Training Centre the radar girls usually wore greatcoats over them as it was pretty chilly huddling in the back of the ration van, especially during a cold wet winter. By midnight they had to be back in camp and safe behind their chastity fence. Those who were unfortunately due on the 03h00 shift, would then try to snatch a short nap.

Generally, however, the leisure hours were spent on the lovely beaches and rocks below the camp. Bathing was delightful, fishing off the rocks popular, and a lot of crayfish were caught by the men. A 21st birthday party was once celebrated with a braaivleis on the beach beneath a full moon - an unforgettable occasion for those not on shift. The radar operators also enjoyed walking on the mountain slopes below the Hangklip overhang. A close watch had to be kept for snakes which were plentiful in the summertime.

From 1943 the stations at Hangklip and Silversands co-operated with the squadron of Catalina flying boats stationed by the Royal Air Force on the Bot River Estuary. The aircraft were equipped with the most modern radar which was maintained by the technicians at Silversands. Information about enemy movements was exchanged and successes were achieved against U-boats and German shipping.

Anecdotes of station life

Due to the secrecy surrounding radar during the War, and the deliberate destruction of papers after the War, no formal, authoritative history of the SSS exists. It can only be pieced together from the memories of the people involved. Much of this informal history comes from the investigations and writings of Corporal Sheila de Beer, later Sheila Lloyd, who served mainly at the Somersveld station, near Darling on the West Coast and at Silversands, one of the three stations in Betty’s Bay, now part of the Overstrand Municipality. She has recounted her experiences and observations in detail, and, almost more importantly, she has systematically collected similar material from other women who were also serving at a variety of 50 or so stations that existed by the end of the war. This section of the Report draws heavily on her work.

Part of the initial training included ‘taking a visual’ – that is, leaving the station building if the aircraft being tracked was close enough and recording a visual identification. This was not as difficult as it sounds as only three types of aircraft that could appear –an Anson, a Ventura or a Catalina. “However, on one delightful and much-remembered occasion, the newest recruit on a shift was sent on one of these recognition sorties without having been properly briefed. Accordingly, she rushed back, wide-eyed, and reported: ‘It is a biplane. It’s got a wing on the right and a wing on the left!’”

On June 16 1944 the Operators at Noordbank station (Saldanha) picked up a signal from the SS Columbine that had (in a real life coincidence) been torpedoed off Cape Columbine. The ship sank quickly but it was learnt later that the second engineer, Harry Haynes, managed to launch a lifeboat with a few passengers and crew. Elizabeth Paine, an SSS operator at Noordbank later spoke to him and learnt what happened:

In the (life)boat was the skipper and his little Chinese wife, an elderly doctor and her husband, and members of the crew, mostly Lascars. The only clothing Harry had was a light overall, which he always wore in the hot engine room. One can imagine the biting cold as they drifted for three days in the icy waters of the Atlantic before they were rescued. The tragedy is that they were close to land and could have been picked up within hours. Harry described how the skipper's wife died in her husband's arms and he just dazedly watched her slip into the water at the bottom of the boat. The skipper himself then died shortly after. The doctor and her husband were huddled at the far end of the boat, suffering dreadfully from the cold and arthritis. Harry saw them discussing something, then the doctor took off her fur coat and handed it to someone and then, to his horror, they stepped over the side into the water. It all happened so quickly no one could stop them. The last they saw of them they had their arms round each other as they sank.

Not all the anecdotes were sad. When Sheilah served at Silversands the issue of pets on the premises came to a head. It all started with too much food, an unusual situation during the imposition of rationing during the War:

Mrs Scott, who for many years had been a stewardess on an ocean liner, was our head cook. The meals were good, healthy and plentiful, but the army was overgenerous with its rations and there was considerable waste. Joan Frost and I, deciding to further the war effort, asked permission to keep two pigs. This was given, and I acquired two large pedigreed white piglets. We named them Ham and Eggs ... inevitably they were much petted and, together with Caesar, they swam and walked with us. Once Caesar became jealous and bit the little one, Eggs, on the neck, exposing fat and lean. Ham screamed and screamed, and we all thought that was the end of his intended wife, but she soon recovered. Mrs Scott liked the pigs, but unwisely fed them titbits at the kitchen door. This led to their invading the kitchen, overturning the slop pails, and other disasters, for which I was not forgiven. One night, Joan and I found their hokkie empty, and searched the camp. Having scoured the main block, we moved to the sleeping quarters. From Mrs Scott's bedroom came a very odd noise - we gingerly opened the door. Mrs Scott - who enjoyed a wee dram or two -was fast asleep, and under her bed were the two pigs. Such a chorus of snores! But, alas, this signalled the end of the pigs at Hangklip.

Also at Silversands the peacetime world of research and scholarly pursuits made itself felt. General Smuts had invited the famous palaeontologist, the Abbé Breuil to study Stone Age artefacts and rock paintings in South Africa and sent him for a day to Hangklip Radar Station. The great man had his interpreter with him so was able to converse with the women operators. Helen Hotson, another of the leading lights at that station, recalls:

Quite near the camp there was a sandy eroded area, which, on our way to the beach, we had crossed many times with unseeing eyes. It was littered with Stone Age artefacts which, until then, none of us had either the wit or the knowledge to recognise. It was virtually a weapons factory. I remember the Abbe sitting on a rock and demonstrating with dexterity how they were fashioned. I am afraid we pillaged the site later for our own collections ... Notice to de-commission the camp came rather suddenly. Robin Hope had made a careful collection of Stone Age weapons, and as he had neither the time nor the means to carry them away, asked me to have them dropped at my parents' house in Somerset West for safekeeping. The engineers' truck was to deliver them, but the heavy box never arrived, so I asked them what happened. The charlatans (sic) said, "What? Those old stones? We threw them away." So somewhere in the veld is a cairn of Stone Age weapons.

Abbe Breuil (SA History Online)

After the war

A draft of this article was read by Patrick Chapman, a member of the Hermanus History Society, who recalled several holidays that he spent with the Logan family at the decommissioned radar station at Cape Hangklip. He contacted Jeanne Jackson (neé Logan) and between them these accounts emerged.

Jeanne Jackson

The Second World War ended with VJ day on the 15th August 1945. I was eight years old. My father, Hugh Duval Logan, was a great friend of Brigadier Van der Hoven, who was in charge of Cape Command. He offered my father the use of the radar station as a holiday house, in return for which my father would keep the roads to the radar station clear of bush and in good condition. My father jumped at the idea and we had a great many very happy times there.

The station was completely empty in the beginning. I didn’t go until Pa had put in beds etc. probably with John’s unwilling help. There were no electrics at all. John later sorted out a generator and batteries but at first it was all candles, paraffin lamps etc. The fridge was quite an early purchase. Cape Jack Clarence who owned Hangklip Beach Estates was a great friend of my father and through him Dad bought two big plots of land in Rooi Els. Harold Porter was another pal of Dad’s and we spent many happy visits together. My father died when I was twelve in July, 1950 but we still continued to have extremely happy times (at the radar station).

I don’t know the date of the Hotel start-up, but later we seemed to eat there at night. I think our Ma’s got fed up with lack of staff! I climbed to the neck of the mountain and also to the look-out high on the mountain. The baboons certainly broke in –we learned to lock all doors on going to the beach. I did not actually see a leopard, but we used to hear fights between them and the baboons at night. We also saw the spoor round the tanks.

Patrick Chapman

It seems the Logans had the station from 1945 to 1958. My recollection is they were asked to leave when reports were made about (ex- military?) perlemoen poachers at the fish traps immediately below the station. The poachers had contacts higher up the military hierarchy.

There were four structures at the site which was narrow, with the mountain looming behind. Describing the structures from Hermanus side, there was first a substantial double storey concrete erection, no walls, on which the actual radar dish presumably had been mounted. This was an empty framework when we arrived. Next, there was a building of two large rooms and two small bedrooms, presumably sleeping quarters for men and women, plus officers. This building was bomb-proof, reinforced concrete, flat roof likewise, and had very thin, tall windows with wooden blackout shutters internally. A single shower was positioned at each end, while the loos were two long drops some way down the slope. Our water was from tanks fed by rain.

The next building was a simple unreinforced construction, with a pitched roof, several separate rooms not connected to each other, each having its own door to the outside. There were standard steel windows. We had them arranged as living room, store, and kitchen/dining room. Finally, a bit further away, there was a generator room which had been stripped of equipment.

To access the splendid beaches, we drove back in direction of the Hotel, then hairpin to beach. It was just too far to walk easily as children. The walk back was steep! There was a pan far below the station on which baboons were frequently seen. In our day there was no direct access to Bettys Bay, which was literally just around the corner. We had to drive back via Pringle Bay to Betty’s Bay for supplies, paraffin, bread, butter and fruit.

At any time, other than Christmas, the beaches and the whole area was pretty much ours. Idyllic really, though we would have enjoyed some bright lights. The vehicle we owned was a Canadian-built 1937 Ford V8, and the Logans had a 1988 Chev. They handled the roads well. In the evenings we drove down en famille to the Hotel where we dined. This gave the mothers a respite from cooking. The hotel's main source of income was from fishermen at the bar. The drive was about 1, 5 kms, along a gravel road to our gate. This had a prominent notice on it: UDF PROPERTY – KEEP OUT

1960 Onwards

The barracks serving the men from the Hangklip Station and the women from Silversands still exist. They were incorporated into the Hangklip Hotel, which was visited recently and the condition of which can be seen in the images below.

Officers Barracks: Hangklip Hotel

Other ranks barracks at Hangklip

The buildings at Silversands became a holiday resort known as Mooihawens. Then, in the 1990s the resort was purchased by the Parow ‘gemeente’ of the Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk and the name changed to Betty’s Bay Oord. It serves as a holiday camp and conference centre for (mainly) youth groups.

The second Betty’s Bay site has been largely demolished or incorporated into modern buildings in Una Drive, Betty’s Bay.

In 2009 the Overstrand Heritage Survey recorded the three radar stations and gave them quite a high conservation rating. The report suggests that they have “considerable military historical significance” and that they represent an “opportunity to form part of a regional historical trail.” To the best of my knowledge no action has ever been taken on this recommendation.

Rear view of women's barracks at Betty's Bay

Conclusion

There are many accounts of the way in which World War II was experienced in the Overstrand area. However, none of the others has such a direct bearing on the outcome of the War as the radar stations around our coast. To my knowledge, they are the only examples where the buildings erected as part of the War effort are still standing, albeit now used for other purposes.

Dr Robin Lee retired to Hermanus in 2001 after a career in the academic world and working in NGOs. In 2003 he started the University of the Third Age in the town and is involved in teaching and administrative work on a voluntary basis. In 2012 he joined a group that wished to formalise the study of the history of the area. This group is now known as the Hermanus History Society. Click here for details of the activities of the Society.

References

- Austin B. A: Radar in World War II: The South African Contribution, Engineering Science and Education Journal, Vol 1, Number 3, June 1992

- Austin, B.A: The South African Corps of Scientists, Military History Journal, Vol 14, No 1, 2007

- Baumann, Nicolas et.al: Overstrand Heritage Survey Report, June 2009

- Bozzoli, G R: Radar in South Africa- The Past, Diamond Jubilee Lecture, Department of Electrical Engineering, University of the Witwatersrand, October 1982

- Brain, Peter: South African Radar in World War II, SSS Radar Book Group, 1993

- Campbell, Keith: The Importance of South Africa’s Radar Capabilities, Engineering News, 12 April 2014

- Cockbain, Tom: Sweeping Circles in the Sky, African Aviation Series, No 14, 2004

- Foster, Gavin: Radar in Durban in World War II, www.fad.co.za, 2008

- Hewitt, F J: SA Radar in World War II: ‘The Outside Story’, Elektron, February 1990

- Hewitt, F J: South Africa’s Role in the Development and Use of Radar in World War II, Military History Journal, Vol 3, No 3, June 1975

- Lloyd, Sheila: Life on the Radar Stations: An Operator’s View, Elektron February 1990, pages 13-22

- Mangin, Geoffrey and Pamela Stevens: Radar Stations – Cape Fortress Command, World War II (1939-1945), SSS Radar Contacts, undated

- Mangin, Geoffrey and Sheilah Lloyd: The Special Signals Service: We scanned the seas and skies in the Second World War, Military History Journal, Vol 11, No 2, December, 1988

- Proceedings of Conference “75 Years: Celebrating Radar Technology in South Africa”, South African Radar Interest Group, November 2014

- Van der Walt, P W and Lia Labuschagne: RRS 25 Years of Innovation: 1987-2012, Reutech Radar Systems, 2014

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.