Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

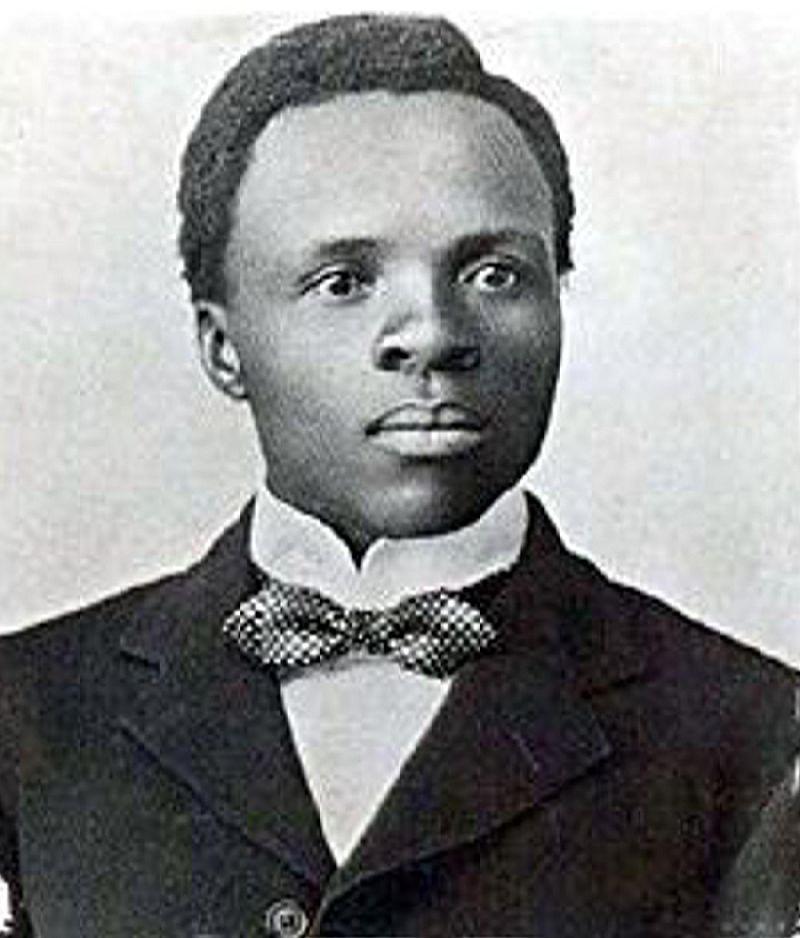

After having been largely forgotten and ignored for decades, in the post-apartheid world of the new South Africa, Sol T. Plaatje (1878-1932), has been hailed as a pioneering figure in the African nationalist movement and the struggle for equal rights. The local authority of the diamond-mining centre of Kimberley in the northern Cape region where he lived for many years and where he is buried, has been renamed the ‘Sol Plaatje Municipality’ in his honour and a new university being established there is to be called the ‘Sol Plaatje University’.

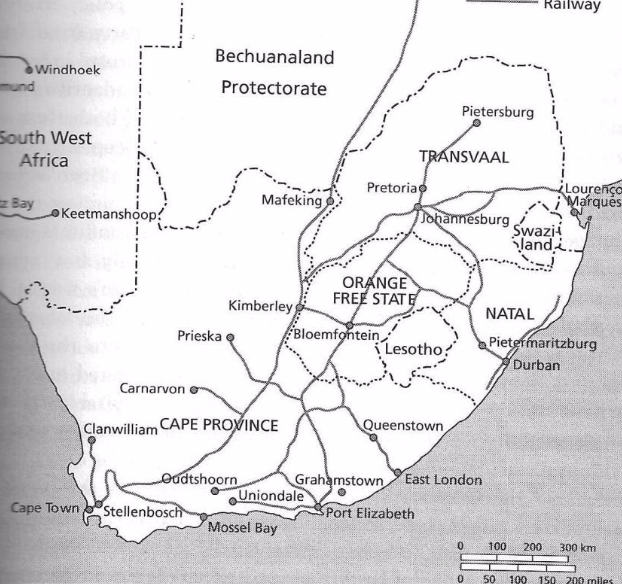

South Africa at Union in 1910

Hitherto, despite the considerable attention recently accorded him, the significance of the bicycle and of cycling in enabling Plaatje to fulfil his role as an activist has been largely overlooked. This article examines how these came to play an important part in his socio-political activities.

The life and times of Sol Tshekisho Plaatje

At the time of his birth in the late nineteenth century, South Africa was not the unitary state it was later to become. Rather, it was an unstable patchwork consisting of British colonies, British protectorates and Boer republics which had resulted from decades of conflict in the region.

Sol Plaatje was born in 1878 in the dorp of Boshof in what was then the Boer republic of the Orange Free State. Ethnically he was of Tswana descent and his family name was Mogodi but, after receiving a formal Christian education at a German Lutheran mission school, he adopted the name Sol Plaatje (pronounced Plaakie) bestowed upon him at the mission.

Sol T. Plaatje (1878-1932)

He excelled in his school studies and then found employment as a youthful post office telegraph messenger in the diamond mining boom town of Kimberley. Later he assumed duties as a court interpreter in the northern Cape town of Mafeking (see map above). While he was employed there, the Anglo-Boer (South African) War broke out between British imperial forces and those of the Boer republics of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State. The war raged across South Africa from 1899 until 1902. At the age of 22, Plaatje found himself trapped in Mafeking when the British garrison there was besieged for eight months from 1899 to 1900 by Boer forces. He served the British troops during the siege and kept a remarkable diary of the circumstances endured in the town at this time.

After the war ended in the defeat of the Boers in 1902, Plaatje again settled in Kimberley which had a sizeable black community that included a mission-educated intelligentsia. There he became the founder-editor of a newspaper published in the Sechuana language and entitled Koranta ea Becoana (Bechuana Gazette). The Union of South Africa, combining the former British colonies of the Cape and Natal with the former Boer republics of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State into a unitary state, was formed in 1910.

The war had taken a terrible toll on both people and property. In rural areas in the Boer republics, the British forces had adopted a ‘scorched earth’ policy, destroying the crops, livestock and buildings on Boer farms and incarcerating Boer women and children in concentration camps where many died either from malnutrition or disease. Simultaneously, many black people fled to the neighbouring territories of Basutoland (now Lesotho) and Bechuanaland (now Botswana) to escape the conflict.

Members of the black intelligentsia to which Plaatje belonged anticipated that, under British indirect rule and through the new Union parliament, black people would come to enjoy a greater degree of socio-political freedom than in the era before the South African War. However, they soon discovered that this was not to be the case as the British Government of the day was primarily intent upon reconciling Boer and Briton in post-war South Africa.

In 1912 a conference was held by members of the black intelligentsia from across the country at which the South African Native National Congress (SANNC) was established with Sol Plaatje, who was by now an established 34-year old newspaper editor in Kimberley, being elected as the organisation’s first general secretary. Its primary aim was to lobby on behalf of the country’s black inhabitants. SANNC was later to become the African National Congress (ANC) which is now the ruling party in post-apartheid South Africa.

The bicycle in South Africa in the late 19th and early 20th centuries

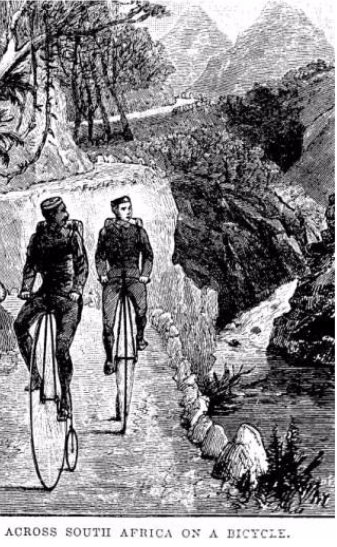

As an outpost of the British Empire, many significant 19th century technological innovations of which the bicycle in its several distinctive evolutionary types was but one, soon filtered into South Africa.

A few ‘Boneshakers’ first appeared on the streets of Cape Town in the 1870s. However, these were rapidly overtaken in popularity by high wheel ‘Ordinaries’ which by the late 1880s were also being raced on cycling tracks in the new gold mining metropolis of Johannesburg. In the 1890s, chain driven ‘safety’ bicycles arrived on the local scene. Cycle racing proved so popular amongst the white residents that a group of Johannesburg gold mining magnates sponsored a local champion to travel to the first official world championships to be contested on safety machines in the USA in 1893, where he promptly won the world paced stayers’ title.

High-wheel ‘Ordinaries’ touring 19th century South Africa

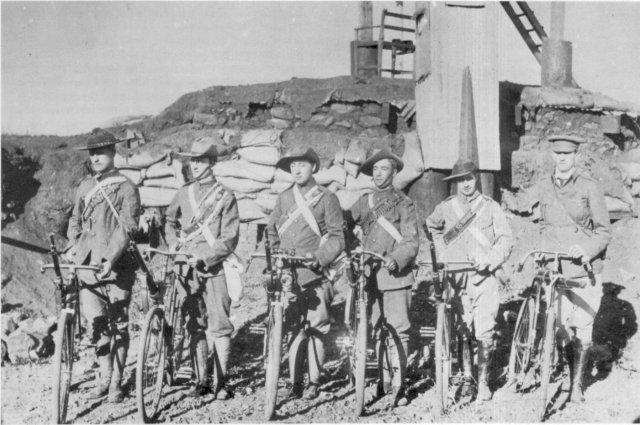

During the 1890s, the popularity of safety bicycles increased rapidly in both urban and rural areas, being used for a variety of purposes: recreation, sport and utility. Then, during the South African War, both sides put safety bicycles to a multiplicity of military uses.

British cycling unit in the South African War (Africana Museum)

Post-war, in the early 20th century, the sturdy utilitarian roadster safety bicycle with pneumatic balloon tyres became a familiar feature of the South African landscape. These machines were mass-produced in Britain by companies such as Raleigh and Rudge. They were tailored specifically to the burgeoning colonial market. Machines of this type could be afforded by even the lowest-paid people in the expanding colonial money economies of the time. Thus, in the early 20th century the large-scale manufacture of utility bicycles in Britain for export to the colonies was stimulated by British colonial expansion in South Africa.

Post-war rural socio-economic conditions in the former Boer republics

Returning to their devastated farms after the South African War, many Boer farmers found it impossible to re-establish their pastoral boerelewe of the 19th century. Lacking finance and having little livestock, they faced a grim future. In the Transvaal, some Boer farmers either sold or abandoned their land to black African farmers; in the Orange Free State it became common for Boer farmers to rent land to African sharecroppers. These practices served to impoverish and displace a growing number of formerly rurally-based white people. They drifted into the towns and cities where they swelled the ranks of ‘poor whites’ and became a major political issue in the new Union parliament.

Largely as a result, a new law – the Land Act of 1913 – was introduced in South Africa. This legislation prohibited black peasants in South Africa from either owning or renting land for agricultural purposes outside of certain specific designated areas. These latter totalled less than eight per cent of the country’s total land area. In terms of the 1913 Land Act, black people could only reside in rural areas outside the restricted ‘designated areas’ if they were employees on white owned farms.

The implications of this were obvious: Africans who had either bought or were renting agricultural land outside the designated areas would be obliged to either become the employees of white farm owners or vacate the land they currently occupied and cede this to whites.

Not surprisingly, the prospect of the 1913 Land Act caused great consternation amongst black African farmers who faced impoverishment and destitution as a result. SANNC, of which Sol Plaatje was the general secretary, reacted to the proposed legislation. As an organisation, SANNC subscribed to the belief that debate and rational discussion with the authorities was the best way to achieve its ends. As a result, SANNC resolved to undertake an investigation into the effects of the implementation of the Land Act as a basis for discussion with the relevant authorities in the South African Government and, if their petition failed, to then seek the intervention of the British Government.

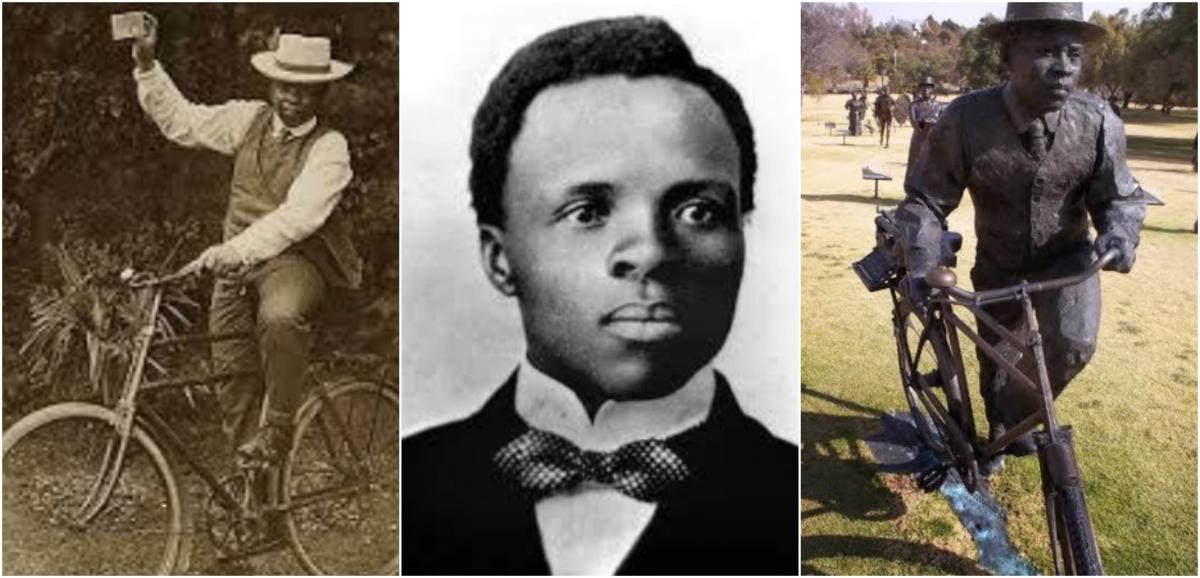

Plaatje, as both a journalist and a key figure in SANNC, immediately decided to embark on an investigation into the effects of the 1913 Land Act on rural black people. He chose to focus primarily on the Orange Free State since this was the most immediately affected province, and also on some parts of the Transvaal and both the northern and eastern Cape. In order to investigate the consequences at first hand, he opted to use a bicycle as his main means of transport. The machine he employed for this purpose was an unremarkable ‘sit-up-and beg’ roadster typical of the period, ideally suited to traversing the rough unmade country roads of the time.

Sol Plaatje on his bicycle and holding up his ‘pass’

Sol Plaatje’s bicycle-based investigation of the 1913 Land Act

Plaatje’s findings concerning the impact of the 1913 Land Act were finally published in 1916 in a book which he entitled, Native Life in South Africa. The book was written in 1914 as he travelled to Britain by sea with a SANNC delegation intent on petitioning the British Government of the day to require the South African parliament to repeal the 1913 Land Act.

Book Cover

Native Life in South Africa is a lengthy and discursive document which includes extracts from debates in the Union parliament as well as from official documents, along with details of his cycling experiences on the road. A close reading reveals that Plaatje must have cycled for an extended period over rudimentary roads between innumerable small dorps, particularly in the Orange Free State. In the process, he encountered many displaced black families, often with their livestock, engaged in a fruitless search for sanctuary. The following are but a few of the experiences he describes:

It is doubtful if we ever thought so much on a single bicycle ride as we did on this journey; however, the sight of a policeman ahead of us disturbed these meditations and gave place to thoughts of quite another kind for - we had no pass…

… In a few moments the policeman was before us and we alighted in presence of the representative of the law … He spoke and we were glad to notice he had no intention of dragging an innocent man to prison … He was a Transvaler, he said, and he knew that Kaffirs were inferior beings, but they had rights … (but) a Kaffir’s life nowadays was not worth a – … ‘Some of the poor creatures,’ continued the policeman, ‘I knew to be fairly comfortable, if not rich … Many of these are now being forced to leave their homes. Cycling along this road you will meet several of them in search of new homes, and if ever there’s a fool’s errand, it is that of a Kaffir trying to find a new home for his stock and his family just now’. Native Life in South Africa (pp.69-70).

It was cold that afternoon as we cycled into the ‘Free’ State from the Transvaal… and towards evening the southern wind rose. A cutting blizzard raged during the night and native mothers evicted from their homes shivered with their babies by their sides…

… Kgobadi’s goats had been to kid when he trekked from his farm; but the kids were now one by one dying as fast as they were born and left by the roadside for the jackals and vultures to feast upon. Native Life in South Africa (p.73)

Plaatje hoped that the contents of his book, including as it did such graphic eyewitness accounts, would add weight to SANNC’s attempt to persuade the British Government to intervene in South Africa and veto the 1913 Land Act. To underline the injustice of the Act, the opening sentence of his book reads:

Awaking on Friday morning, June 20, 1913, the South African native found himself, not actually a slave, but a pariah in the land of his birth. Native Life in South Africa (p.22)

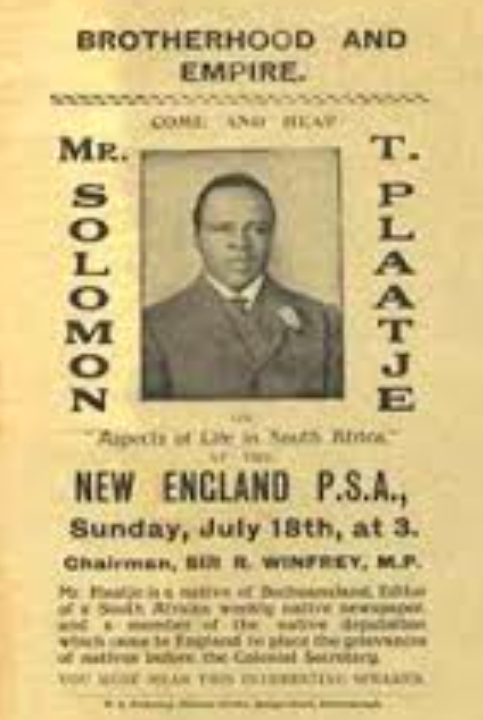

However, as matters turned out the British Government of the day was totally preoccupied with the First World War. Given the existence of German colonies in both east and south-west Africa at that time, it was considered more important to cultivate the South African Government as an ally. Thus the 1914 SANNC mission proved a failure. Another delegation which also included Plaatje returned to Britain in 1919 and succeeded in meeting with the then British prime minister, David Lloyd George, who was sympathetic but declined to intervene. Plaatje subsequently independently visited the United States where he met with early African-American civil rights activists and was a guest speaker at several of their meetings.

US Poster advertising public speaking engagement

Sol Plaatje died in 1932 at the age of 54 and was buried in the black cemetery in Kimberley. In 1935 a tombstone was erected on his grave bearing the inscription: 'Rest in Peace Morolong: Servant of Africa.'

In 1991, nearly 80 years after it was enacted, the 1913 Land Act was finally removed from the South African statute book. Viewed in retrospect, Plaatje’s vivid recording of what he found in traversing the dusty back roads of rural South Africa on a simple bicycle in the early part of the 20th century was the first step in a process which led to this end.

Statue of Sol Plaatje in the Heritage Garden of the Oliewenhuis Museum, Bloemfontein (Sean O’Toole)

The life of Plaatje has also been celebrated at Kedar Heritage Lodge (Kathy Munro)

Archie Barnwell, friend, colleague and protégé of Geoff has taken on the task of ensuring that Geoff’s work on the “untold" history of Cycling in South Africa reaches a wider readership as this sporting history and the impact of racial division and apartheid make this yet another South African story worth telling.

About the author: Geoff Waters passed away in November 2018. He was a Sociology Lecturer at the University of Kwa-Zulu Natal, and after his retirement wrote a number of South African Cycling related history articles. He was dedicated to recording the untold South Africa Cycling sporting history and researched archives and press cuttings and interviewed a number of cycling figures involved in the promotion and participation of apartheid era cycling sport.

He was a passionate cycling enthusiast, with an intense interest in international and local cycling . He played a key role in many young cyclists' lives, with words of advice and encouragement. He served in a number of administrative roles in Kwa-Zulu Natal cycling, and was instrumental in the organisation of a number of major cycle racing events. Geoff wrote a number of articles which have been published in the “Classic Light Weights” UK cycling magazine and for South African cycling newsletters and online portals. He completed the “100-Year History of Kings Park Cycling Club - Durban” in the past few years and this final work “History of Natal Cycling” is pending publication in the Zulu Natal History journal.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.