Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

"The geographical map ... although static, implies a narrative; it is ... an Odyssey." Italo Calvino, Collezione di Sabbia, Milan 1984.

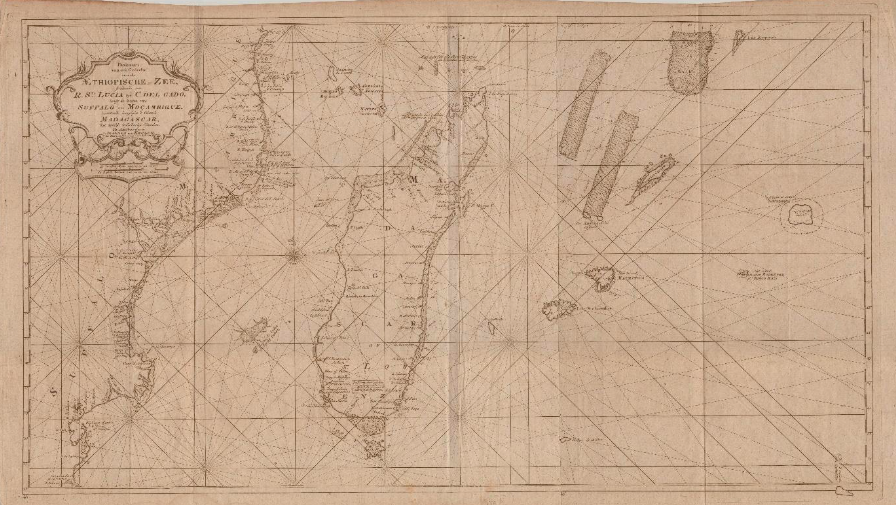

I had just completed cataloguing the Schrire Africana map collection of more than 600 items that had been dormant for almost half a century. Catalogues tend to be formal, technical and predictable. One of the maps was a scarce sea chart (see main image and click here for a high res version) I had not seen before and that was not mentioned in any of the reference books on maps of southern Africa. In a sale catalogue I found a brief description of the chart. it piqued my curiosity.

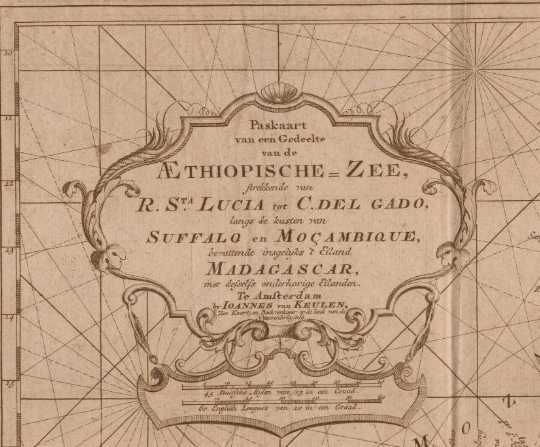

Here is an English translation of the full title: “Sea chart of a Part of the Ethiopian Sea; stretching from Rio St. Lucia to Cabo del Cado, along the coasts of Suffalo (Sofala) and Mozambique, also containing the island of Madagascar and its dependent islands. In Amsterdam by Johannes van Keulen, sea chart and book seller at the corner of the New Bridge Alley.”

The map title

The detailed title did not tell me where it came from, but the Van Keulen name was a clue. Fortunately, Leen Helmink, a Dutch dealer in antique maps had done the basic homework for me.

“Madagascar – Seychelles. Extremely rare collector’s chart that was published only in the secret atlas of the Dutch East India Company, for internal use. Hardy ever in the market. No doubt the very best and most detailed early chart of the region...”

I could find only two other examples of the chart. The Dutch National Archives has a coloured copy and there is also an example in the National Library of Portugal.

The Secret VOC Atlas

The chart first was published in 1753 when it was included in the ‘secret VOC Atlas’, which a popular description of Part VI of the Nieuwe Groote Lichtende Zee-Fakkel (The New Great Shining Sea Torch). The author was Johannes van Keulen II (1704-1755), hydrographer for the VOC and the grandson of the patriarch, Johannes van Keulen I (1674 – 1715). Part VI was the pilot-guide for sailing between the Netherlands and the East Indies: Van Keulen provided the sea charts, while Jan de Marre provided the text.

The Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC), the Dutch East India Company, was established in 1602, a Dutch trading company established by royal charter and the first ‘joint stock’ company in the world. For 150 years the VOC produced only manuscript charts: hand-drawn on vellum, specially prepared animal skin or membrane. The VOC did not publish printed sea charts of the area east of South Africa because of its strategic importance: the VOC dominated trade with the Spice Islands from its regional headquarters in Batavia (today’s Jakarta in Indonesia) and wanted to protect its competitive advantage.

Painting of Batavia

Johannes I’s first volume of the Zee-Fakkel was published in 1681. In 1753, Johannes II, his grandson, completed the magnum opus by publishing the sixth and final volume. The atlas was a milestone in maritime cartography: sea charts and sailing instructions for the long voyage between the Cape of Good Hope and the Far East.

The development and publication of the sixth volume had been obstructed by the Heren XVII (i.e. the board of directors of the VOC) but now it was available – but only for the VOC!

The Secret Atlas of printed sea charts, like the VOC manuscript charts, was never sold to the public. They were issued to the captains of VOC ships for one voyage only… and they had to return them on completion of the voyage. Very few examples of the atlas have survived.

The chart

This ‘Sea chart (is) of a Part of the Ethiopian Sea (i.e. Indian Ocean); stretching from Rio St. Lucia (in today’s KwaZulua Natal) to Cabo del Cado (on the northern coastal border of todays’ Mozambique)’.

The chart includes all of Madagascar, the Comoro Islands (Gasidsa Comoro, i.e. Ngazidja or Grand Comoro), Mohila, Anjoana and Mayota) and Mascarene Islands (Mauritius, Rodriques and I. de Mascarenhas, i.e. Reunion). The chart identifies the Portuguese factories (trading posts) at Suffalo (Sofala) and Mocambique Island with its Fort San Sebastian (‘Eiland and stad Mocambique’ at about 15°15’S on the chart).

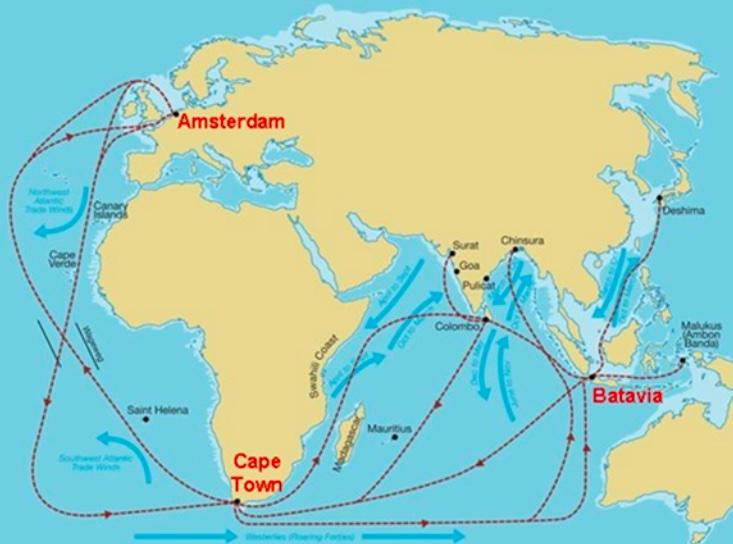

The sector of the sea route on the eastern coast of Africa and Madagascar was all-important for ships trading between Europe and the Far East.

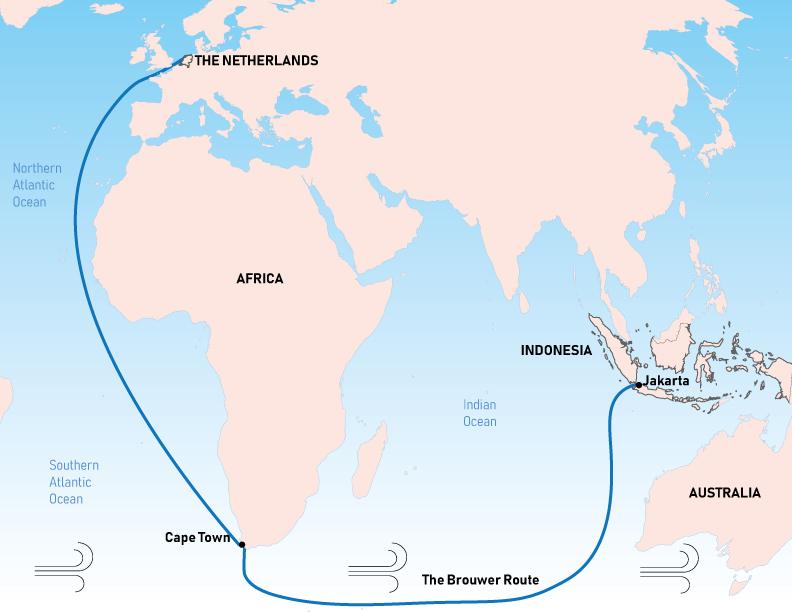

There were numerous routes to and from Batavia. The selected route was determined by VOC policy, weather and currents and also the captain’s preference. The outbound voyage usually went through the Mozambique Channel unless the captain selected the faster Brouwer Route in the roaring forties. The problem with this route was sighting of the tiny islands of St Paul and/or Amsterdam in the southern Indian Ocean; when sighted, the ships would head north. Failure to sight these tiny islands sometimes resulted in wrecks off the western coast of Australia. The faster Brouwer route was not favoured by the English.

Routes to and from Batavia

The faster Brouwer Route

Trade and pirates

The east African coastal region on the chart is labelled Suffalo (Sofala). The fort (and port) of Sofala is shown at about 20° east. It was the oldest harbour in southern Africa, first a Swahili port but also used by Arabs from about 915 CE for the purpose of trade in gold from Zimbabwe. Persian Muslims settled in Sofala during the 14th and 15th centuries. Then in 1505 the Portuguese occupied Sofala and built a fort and trading centre in the hope of capturing the gold trade previously held by the Arabs. As the gold was depleted, Sofala port went into decline and has been replaced by Beira about 30 km to the north.

The area included in this chart was also used by slave traders. The shoals on the north-west coast of Madagascar were discovered by the slave trader ship Firebrass (this discovery is reflected on the chart with the annotation‘’ontdekt deur door’t schip, Firebrass 1682’).

Antongatt, i.e. Antongil Bay on Madagascar, and nearby St. Mary’s Island (Nosy Bohara) were also particularly notorious for its pirates, such as William Kidd, Henry Every, John Bowen, and Thomas Tew. Pirates’ graves are scattered over St. Mary’s and other islands of Madagascar.

Pirate graves are scattered over the islands of Madagascar

Scurvy

Scurvy developed within six weeks of a diet deficient in Vitamin C – on long voyages almost a third of sailors (many malnourished when they boarded) suffered from and died from the disease as a result of a diet devoid of fresh fruit and vegetable. Vasco da Gama had reported the first cases of ‘sea scurvy’, which occurred during his 1497 voyage to India, and also reported the cure of the disease by eating fresh fruit he obtained from indigenous inhabitants along the east African coast – a lesson learned and forgotten for centuries. Madagascar was also a source of fruit, first successfully exploited by the English East India company in 1601 by Captain James Lancaster.

Van Keulen included a small box of text in southern Madagascar explaining that the placenames were derived from the Portuguese and English. So, 'Ilha do Nascimento', on the south-east coast of Madagascar, was better known to the Dutch as Hollandse Kerkhof (Nosy Manitse, today), the ‘cemetery of the Dutch’: the burial ground of many Dutch sailors during the 1595 voyage of Admiral Cornelis De Houtman to the East Indies. Most had died of scurvy, which was relieved when the ships touched the eastern African coast, in and beyond the channel, where they received fresh fruit from the indigenous inhabitants. Scurvy and lack of fresh water continued to beset the party on the return voyage; they returned to the Netherlands with only 87 of the original 249 crew – too weak to moor the boat without assistance.

Nosy Manitse (Google Maps)

That's the thing about old maps. They let you travel in space and time without moving your feet. (Apologies to Jhumpe Lahiri, The Namesake, New York, 2003)

Main image: Paskaart van een Gedeelte van de Aethiopische-Zee [Sea chart of a part of the Aethiopian Ocean], 88 x 50 cm.

For more information contact Roger - roger@africanamaps.com

Roger practiced medicine, was associate professor of human physiology, and has been an executive and director of businesses locally and abroad. He has also collected historical maps of South Africa and the continent of Africa; these maps are now conserved at the University of South Africa and Stanford University, USA. His articles on the maps and Cape history have been published in international journals and local periodicals.

References

- Jaap Bruijn. Between Batavia and the Cape: Shipping Patterns of the Dutch East India Company. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 11, no. 2 (1980): 251–65.

- Roger Stewart. Scurvy, the Cape of Good Hope and Delayed Learning in A Cape Odyssey, Vermont, Footprint Press, 2021

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.