Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

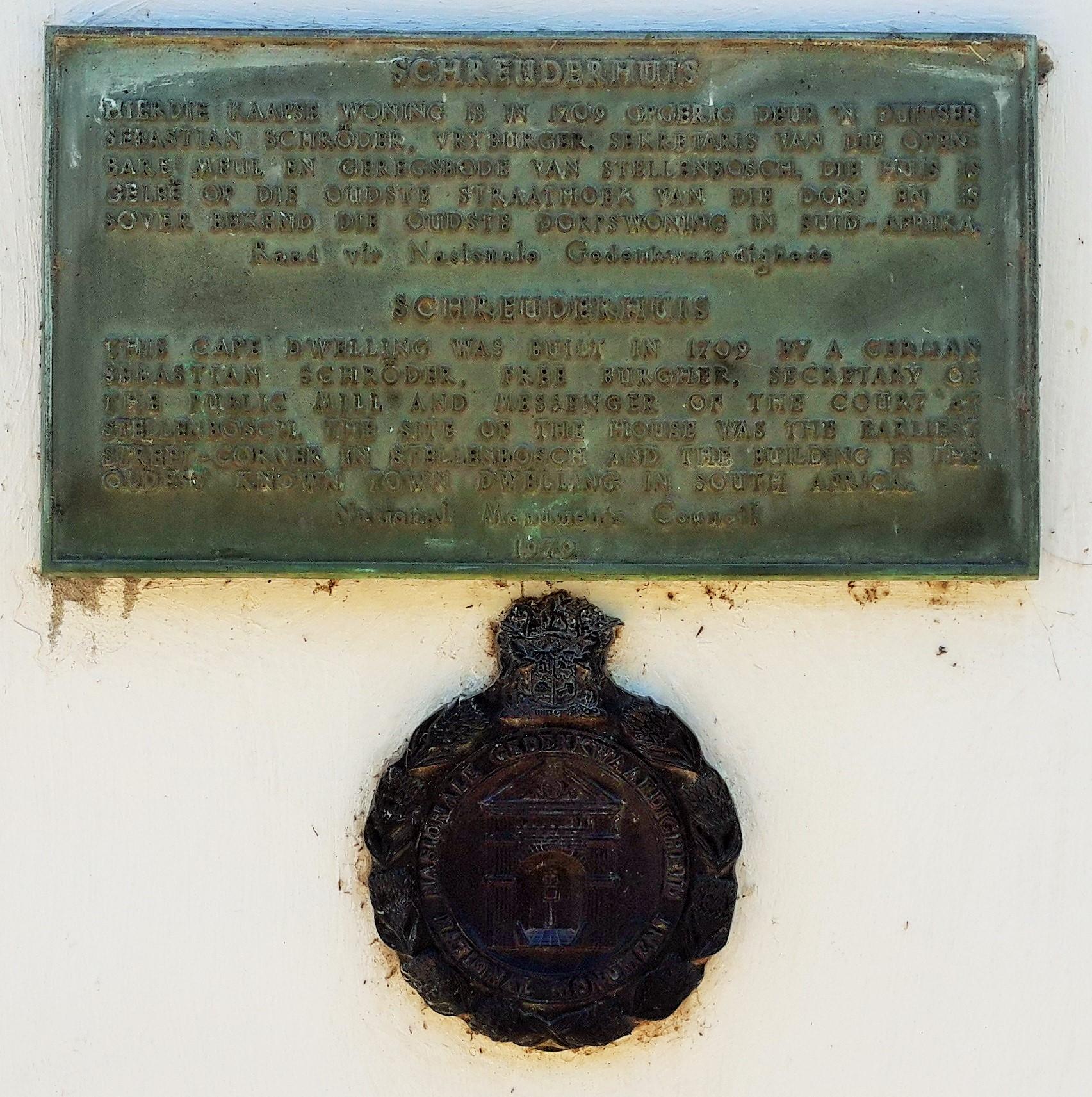

In the article below, originally published in 1975, Gwen and Gawie Fagan look at the history and restoration of Schroder House in Stellenbosch. The article appeared in Restorica, the journal of the Simon van der Stel Foundation (today the Heritage Association of South Africa). Thank you to the University of Pretoria (copyright holder) for giving us permission to reproduce here.

History

Sebastian Schroder was a German from Scfledehausen in Lower Saxony who joined the VOC as a soldier and arrived at the Cape before 1707, the exact date not being known.

On the 3rd August, 1707 the Stellenbosch College of Landdrost and Heemraden employed him for a year on a loan basis from the Company to act as secretary for their public mill.

It is not known where Schroder lived during this period nor how long he worked as the secretary for the mill before being appointed court bailiff. It is, however, known that he had become a free-burgher by October, 1709, when he was granted two house-erven by Governor Van Assenburg, on the corner of Van Ryneveld and Church Streets. No mention of buildings is made on the grant but we have reason to think that at that time Sebastian Schroder had already built a very small dwelling, probably with only one room, parallel to Church Street and that he might have been living there whilst working as secretary for the mill. In January 1710, the traveller Evan Staden sketched the little town, and on this same house-erf we now see a building standing parallel to Van Ryneveld Street. Schroder had then been appointed court bailiff and it is our surmise that he extended his humble dwelling by adding three rooms at right angles to the west wall to form a T -shaped house. This must have been during 1709 either before or directly after the official grant of his erven.

As court bailiff - it can be presumed that he would have had reasonable access to wood, of which the Company at that time had a plentiful supply at Hottentots Holland, so that these rooms although built of clay, could have had substantial ceiling-beams and a well-constructed roof - all of indigenous wood.

On the 13th of January, Schroder, for some unknown reason, decided to sell his house to Johan Barentz Sieker for the sum of 1 100 guilders, but this transaction was never executed. Maybe Schroder changed his mind as a result of his marriage to Sara Wijnsandt two months later on the 9th of March, because the couple lived in this house for the rest of the year.

On the 17th December, 1710, about ten o'clock in the morning, the landdrost sent a slave to his kitchen for a coal to light his pipe. But a sudden gust of wind blew sparks into the roof, setting it alight, so that very soon the Drostdy with its stable was burning. A strong southeaster quickly spread the flames to the houses in the vicinity as well as the church to the south-west of Schroder's house. It seems unlikely that Schroder's house, which was in the way of the flames, should have escaped damage. During the restoration the clay walls in the back section of the T revealed no signs of previous fire damage - but in the mud brick walls of the three front rooms there were two areas of clayed-up wall which very obviously were relics of an earlier structure. It seemed likely that the front part of Schroder's house had burnt down and that he rebuilt these three rooms on the old foundations of stone and mud, but keeping those parts of the old clayed-up walls that had remained standing, and patching where necessary, with the mud bricks.

During 1711 Schroder and his wife moved to Cape Town, probably while the house was being rebuilt, but where he lived in Cape Town or what work he did there, is not known.

Early in 1712 he asked permission from the Council of Policy to sell his property on public auction and to return to Europe. His Stellenbosch house was thus sold to Abraham Everts on the 9th February, 1712 for 700 guilders, and on the 29th March, he sailed with his wife back to Europe.

From that time Schroder's house changed hands many times; in 1756 it belonged to the sexton Coenraad Fick who later owned all the property between Plein Street, Church Street, Van Ryneveld Street and Drostdy Street. In 1776 this large property was bought by Christiaan Krynauw, the sick-comforter and after his death his widow Maria Elisabeth Groenewald subdivided, selling the northern portion to landdrost Bletterman. Here the magistrate's court was built.

Other owners were Johannes Gysbertus Faure 1840, 0 M Bergh 1848, and Tielman de Waal in 1901. In 1904 the eastern side of the property was deducted and sold to the Roman Catholic church, leaving the original Schroder house and erf very much smaller. In 1940 Andries Petrus Lubbe bought Schroder's house whilst the Municipality of Stellenbosch bought the portion that had belonged to the Roman Catholic church.

In May, 1970, Lubbe applied to the Stellenbosch Town Council for permission to demolish his house, and this was granted. However, many indignant voices were raised in defence of this and through the intervention of the Provincial Administration, demolition was prevented and the house eventually bought by the Stellenbosch Museum, who are responsible for its restoration. The house will be used as an extention to the Grosvenor House Museum.

Schroder House (The Heritage Portal)

Restoration

The restoration of this simple little house has caused more headaches than many larger and more imposing projects: little is known about country houses of this period, the Van Stade drawing of 1710 on which Schroder's house is depicted is neither accurate nor clear and the house has undergone so many changes that it would require a clairvoyant to decipher the chronology of the construction. Despite hours of detective work on site, our final plan was based on informed guesswork and may prove inaccurate should further knowledge of this period become available.

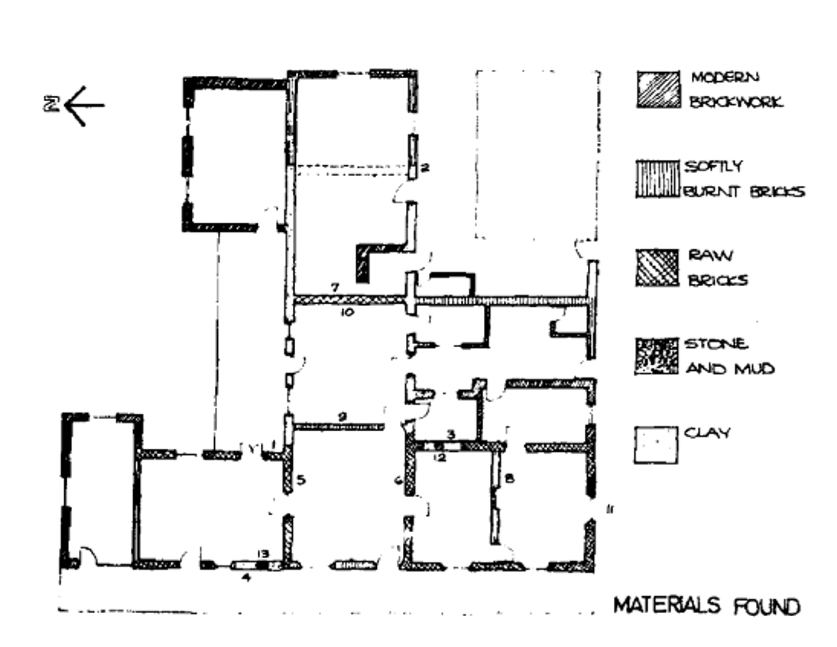

The Walls

A study of the different wall materials indicated that the back wing of this T-shaped house was originally built of 300-400 mm thick layers of yellow clay, while the front rooms were constructed of unburnt mud bricks and mud mortar. Where these two materials meet (no 1) on plan, in the left corner of the T, the plastered outer surface of the clay wall forms a clear cleavage line, with the mudbrick wall built up hard against it, obviously at a later date. A similar cleavage-line between clay and later brick walls at the eastern end of the T -wing (no 2) indicated where this original end-wall of the house had been, and although there was no sign of the old wall itself the foundation, consisting of large stones, was unearthed when the wall \vas reconstructed in this position. It was now clear to us that the first house on Schroder's property had been a single-roomed cottage, and that three rooms had been added later at right angles, to form a T -shaped house.

Did Schroder build this simple dwelling to live in while he was secretary for the mill? Then this part of his house would date back to 1707. The stone foundations of the front part of the house are carried to a height of approximately 500 mm above the floor level, are continuous and show no disturbance, but there are two areas in the mud-brick walls at (3) and ( 4) where portions of earlier clay walls exist and, as the mud-brick are built overlaying the clay, one must assume that some disaster befell these earlier clay walls and that they were rebuilt with mud-bricks on the old foundations.

Could the fire of 1710 have been responsible? We think this very likely. We noted that this clay was darker in colour, more friable and contained much more vegetable matter than the yellow compacted clay of the back wing - thus strengthening our assumption that the two sections were built at different stages. Of the inside walls, those at (5), (6) and (7) were built of the same early yellowish flat bricks as the outside walls, but those at (8) and (9) were built of soft burnt red brick and buttered against plastered walls - so they were obviously not part of the early house plan and consequently demolished.

The Hearth

Where T-shaped houses are described by early travellers and also in our own experience, the kitchen is invariably placed in the back wing of the T against the end wall. The traces of earlier flues and soot against the wall at (10) did not indicate an original fireplace, for these marks crossed an old bricked-up door opening.

Van Stade's sketch shows no front or side gables nor a chimney stack. So we had no clear evidence of where the original hearth had been. Arguing that the first house probably had an inside fireplace, and ruling out the wall at (10), we decided that it could well have been against the western wall where it could have been retained when Schroder extended his house. Consequently this wall was rebuilt, in line with the cleavage line at (1), with a small hearth and baking-oven constructed on the pattern common to existing similar hearths.

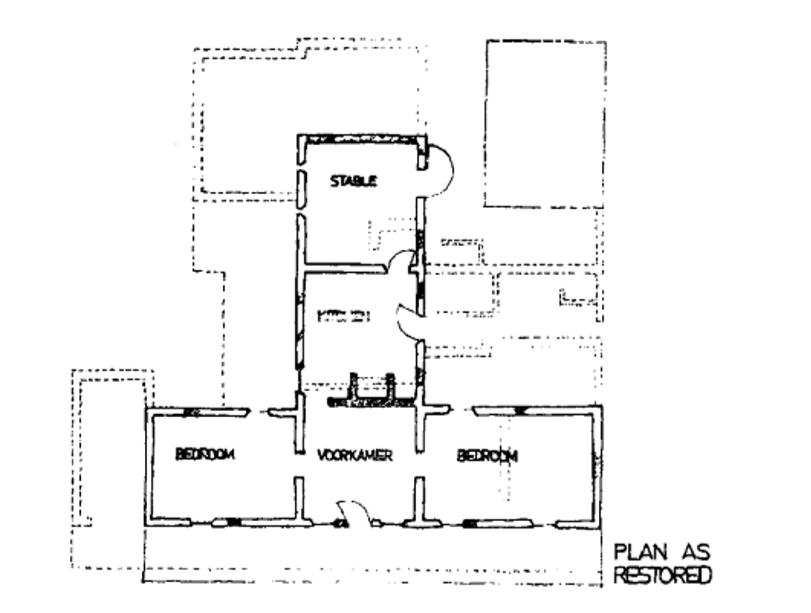

The inside plan was now complete: voorkamer, bedrooms to the right and left, a kitchen at the back with a door leading through to a stable in the tail of the T. As Schroder was required to serve summonses, arrange judicial sales, gather information for civil cases and apprehend prisoners, it is highly probable that he would have had a horse readily available, and thus a stable. One aspect of the plan which worried us, was the large size of the room on the right. Would a primitive house like this have had such a large bedroom?

Today a bedroom houses one, two or three people at the most, but early travellers like Burchell, Pringle, Thomas and Hudson describe how in those times all the females of the household would sleep in one room, with all the males in another. Moreover, if the house consisted of one large room only, the females would sleep at one end behind a screen of mats whereas the males (and visitors) would sleep between the dining table and hearth, stretched out on blankets or mats on the floor!

It has often puzzled us that these early houses had so few rooms - although often quite large - to house such large families. (Think of Jean de Villiers at the original Bosch-en-Dal with 22 children, or Gys bertus Keet at Tulbagh with eleven sons in a simple T-shaped cottage). Privacy is a modern conception as also our preference for many small rooms, rather than a single large one. It could also be that Schroder used this room as a lock-up area for prisoners awaiting trial, in which case the windows should have bars.

Another aspect of the plan which needed clarification, was evidence of a bricked up door in the south wall of the right room at (11). Here the brickwork had been irregularly cut back at the reveals, and the fact that the pintles for the hinges of the double door were built in with cement, indicated that this opening was made at a very late stage in the history of the house, when the right room probably served as waggon house, smithy or some such workshop.

The Windows and Doors

We were fortunate to find two bricked-up window openings in the remaining clay walls of the front section of the house at (12) and (13), ie in the oldest part of the front section. These openings both measured 1,150 x 0,950 m and at (12) the impression of an old wooden frame, (100 x 125 mm) was found in line with the outer surface of the wall, so that window frames and shutters were made to fit these openings. The positions of the other windows were not clearly indicated in the brickwork and were therefore mostly placed In existing openings.

Very little was left of the original wall round the front door, so that the positions of this door and of the windows to the voorkamer were guessed at. As is still usual in simple houses, it was felt that this house would also not have had internal doors, except between the stable and kitchen. One reveal of the kitchen back-door in the clay wall was discovered at (14) and the stable-door, designed in accordance with similar doors still, to be found in old outbuildings, was positioned here. Travellers like Mentzel, Burchell and Pringle all mention the lack of glass in the windows of country dwellings, so one must assume that Schroder would not have used glass, but at best, linen on frames as described by Burchell.

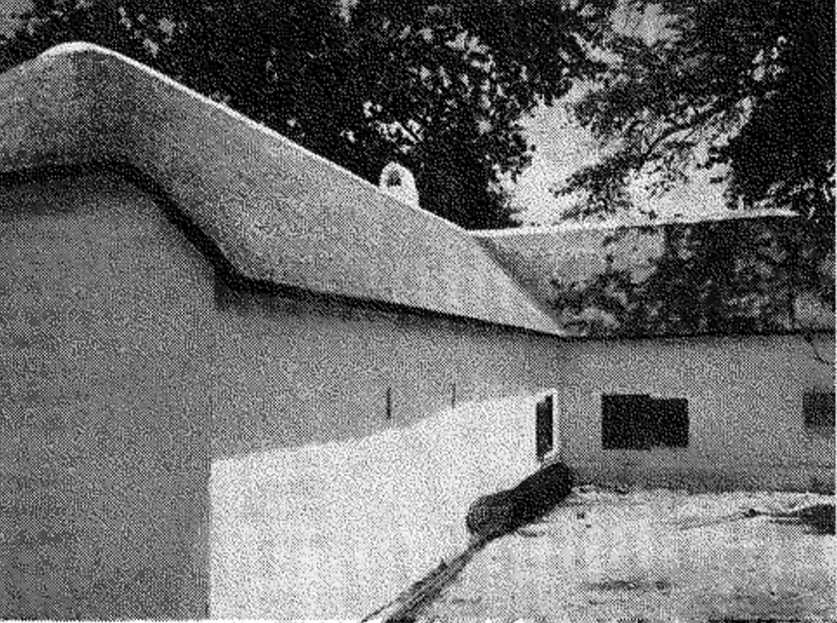

Schroder House seen from the rear (W Marsh)

Floors

In 1811 Burchell noted that even those farmers who dwelt in the vicinity of forests preferred earthern floors in their houses, and this obviously would be the case as flooring planks and nails were hand finished and therefore scarce - probably much more so in 1710, when Schroder built his house.

Ceilings

For similar reasons boarded ceilings would have been hard to come by, and if the bailiff wanted a smart ceiling he would have had to resort to reed ceilings. We know that Spanish reed (Arundo Donax) was first imported and planted in the Company's gardens in 1660 and that according to Thunberg it was plentiful in the Colony in 1774, so we can safely assume that by 1710 it would have been used in Stellenbosch.

Timber

The supply of timber had steadily dwindled towards the end of the 17th century so that by 1700 some of the French Huguenots did not have enough timber to construct houses for themselves and requested the Council of Policy to supply them with 3 000 deal planks, as well as doors and "sparre" for building purposes. In that year, however, Willem Adriaan van der Stel had travelled to the Waveren Valley and here a plentiful supply of wood, suitable for building purposes, was discovered. This timber was used in the surrounding areas during the early part of the 18th century. Forests at Hottentots Holland were also being exploited by this time, so that Schroder, as an employee of the Stellenbosch College of Heemraden, would have had no difficulty in obtaining suitable timber for his house. A report made by the Company's carpenters in 1663 tells us which of the indigenous woods were regarded as suitable for building purposes; essenhout, Cape ash (Ekebergia capensis ), poekenhout, Cape beach (Rapanea melanophloeos), pearwood (Apodytes dimidiata), assegai-wood (Curtisia dentata), and yellowwood (Podocarpus species), which was regarded as most suitable and was three times the price of the others.

In later buildings in the country, poplar was extensively used for roof-construction, but as poplar seed was imported by Van der Stel only in 1700, Schroder obviously would have used indigenous timber. The Department of Forestry very generously agreed to our suggestion and felled the necessary trees in their forests, for the construction of this roof. As the timber had to be dried and treated, the restoration was delayed for almost a year as a result.

Traditional construction methods were followed in putting up the roof and the next task was to ascertain what thatching would have been in use in 1710 - obviously that which grew in the neighbourhood. Dr J Rorke from the Kirstenhosch Herbarium was most helpful at this stage and although we at first thought that grass would have to be especially cut at Macassar in the dunes, we were overjoyed to hear that the ordinary thatching grass, which is still used today (Thamnocortis spicigerus) would be quite correct, as it was indigenous to this area. The same applied to Palmiet (Priomum Palmita) which is still popularly used as a "spreilaag" or underlay.

Finally the door handles and latches had to be designed from existing prototypes, and hand forged. The barrel bolts on the windows have been copied from a very early Tulbagh house (Klipfontein) but unfortunately they should not have been welded together! The wooden door latch some of you may remember from a previous Vernac outing to Elandsvlei.

Old National Monument Plaque and Inscription (The Heritage Portal)

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.