Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Kenneth Charles ‘Ken’ Bath (1915-1985) was a professional photographer in the 1930s and went on to run the photographic division for Anglo American. The family of Ken Bath have made his collection of photographs available to The Heritage Portal (click here for details of the collection). The photographs selected for this article are of the Braamfontein Yards and the impressive Braamfontein Coal Stage used for filling the coal tenders of the outgoing trains. It is estimated that the photographs were taken in the late 1940s or into the 1950s.

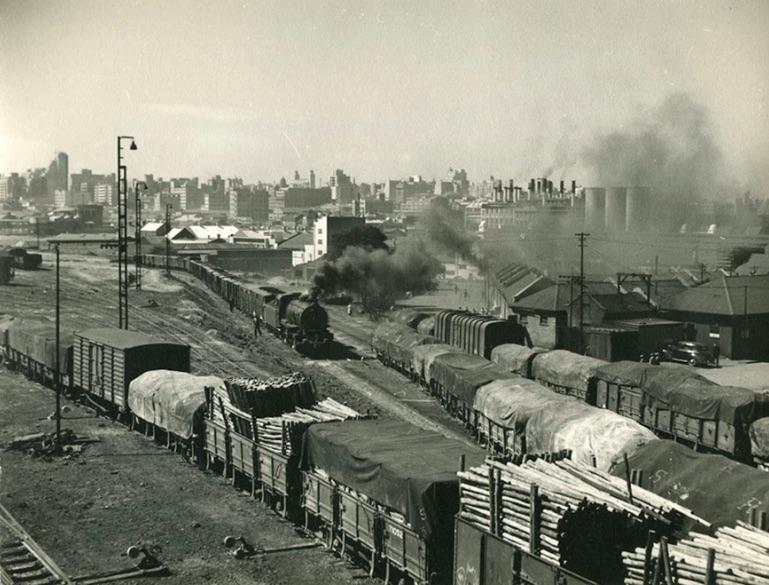

Class S shunter in the Braamfontein Yards. The building in the upper centre of the image is the Market Cold Storage building which is still in existence. (Bath Family Archive)

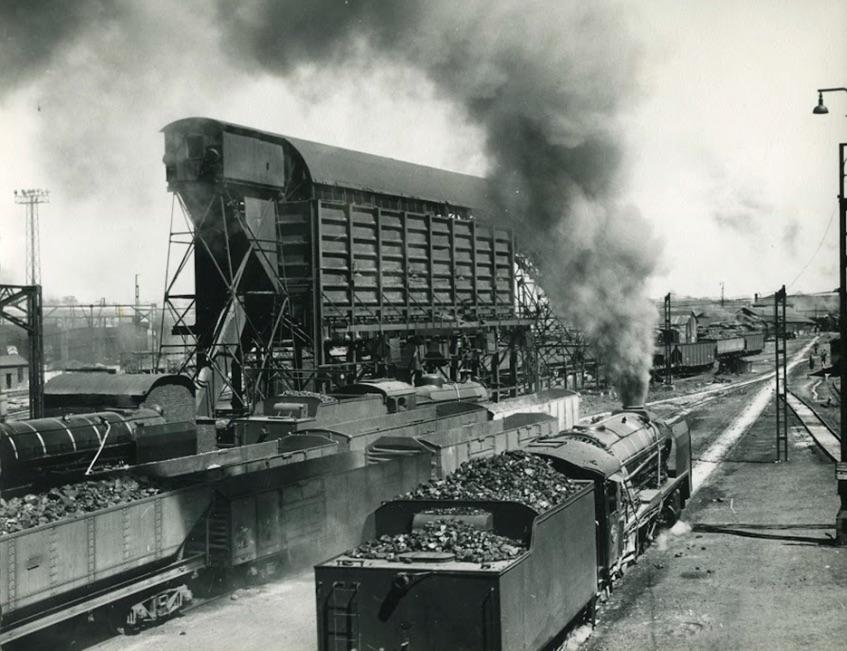

Massive Braamfontein Coal Stage (Bath Family Archive)

When the Witwatersrand started its rapid development following the discovery of gold in 1886, industrial infrastructure was almost totally absent in the Transvaal because of its agrarian economy. It soon became clear that the slow transport wagons could not keep up with the demands from the increasing number of mines which needed heavy construction materials and coal. As a source of electrical energy, coal was of crucial importance to the gold mines. In 1886 coal had been found at Boksburg, but a quick and efficient method was still needed to transport it to the gold mines and then to the city itself, for electricity generation, and this was by rail.

The Nederlandsche Zuid-Afrikaansche Spoorweg-Maatschappij (NZASM) was a Dutch company established in 1887 to build the railway lines linking the Witwatersrand to the Mozambique port of Lourenço Marques. They also built the railway line south of the Johannesburg CBD to facilitate the movement of coal, construction materials, other goods and provisions to the Witwatersrand gold mines and to the thriving new city of Johannesburg.

The 1913 Market Hall and the Market Square in front of it became major economic and trade hubs for the city, but these facilities had to be close to a railway line. By 1937 all available land at the Kazerne, Newtown and Braamfontein areas had been put to use, but this was still inadequate to meet the city’s rapidly increasing requirements. After the Second World War, work began to replace the old goods depot in Braamfontein with a new goods depot to the south east of the Johannesburg CBD, with construction completed by 1952. This massive goods yard became the City Deep inland port and container terminal in 1974.

Market Building Newtown nearing completion 1912 (Museum Africa Archives)

While we all have accepted that Johannesburg had its own electrical power stations from early in its history, we might not have realised that this meant moving vast amounts of coal around and bringing it into the centre of Johannesburg to fuel the power stations. Such was rapid technological progress in the new city that by 1910, many of Johannesburg’s suburbs were supplied with electricity. In 1902, an electric tram network was also established supplied by private electricity companies. As the demand for electricity grew after the First World War, a new city power station was commissioned. This was the Jeppe Street Power Station and by 1927 it was in operation. It consisted originally of a shorter Turbine Hall and a single “North Boiler House”, but even this station could not keep up with the city’s demand for electricity and in 1934, the South Boiler House was built and the Turbine Hall extended. The new Jeppe Street Power Station consumed a trainload of coal a day.

Turbine Hall (The Heritage Portal)

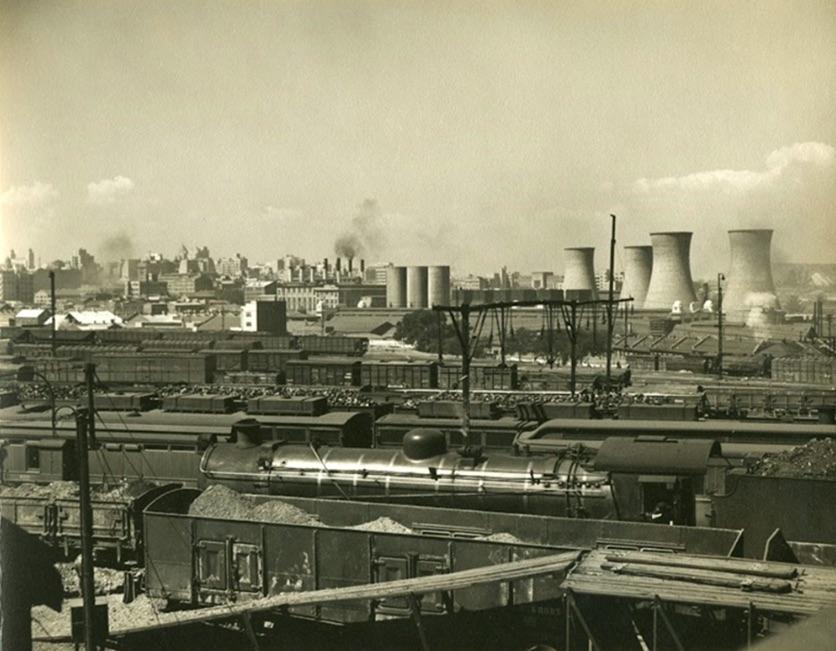

Braamfontein Yards with the Jeppe Street Power Station and four cooling towers in the background (Bath Family Archive)

A blue plaque commemorates the history of the Jeppe Street Power Station (The Heritage Portal)

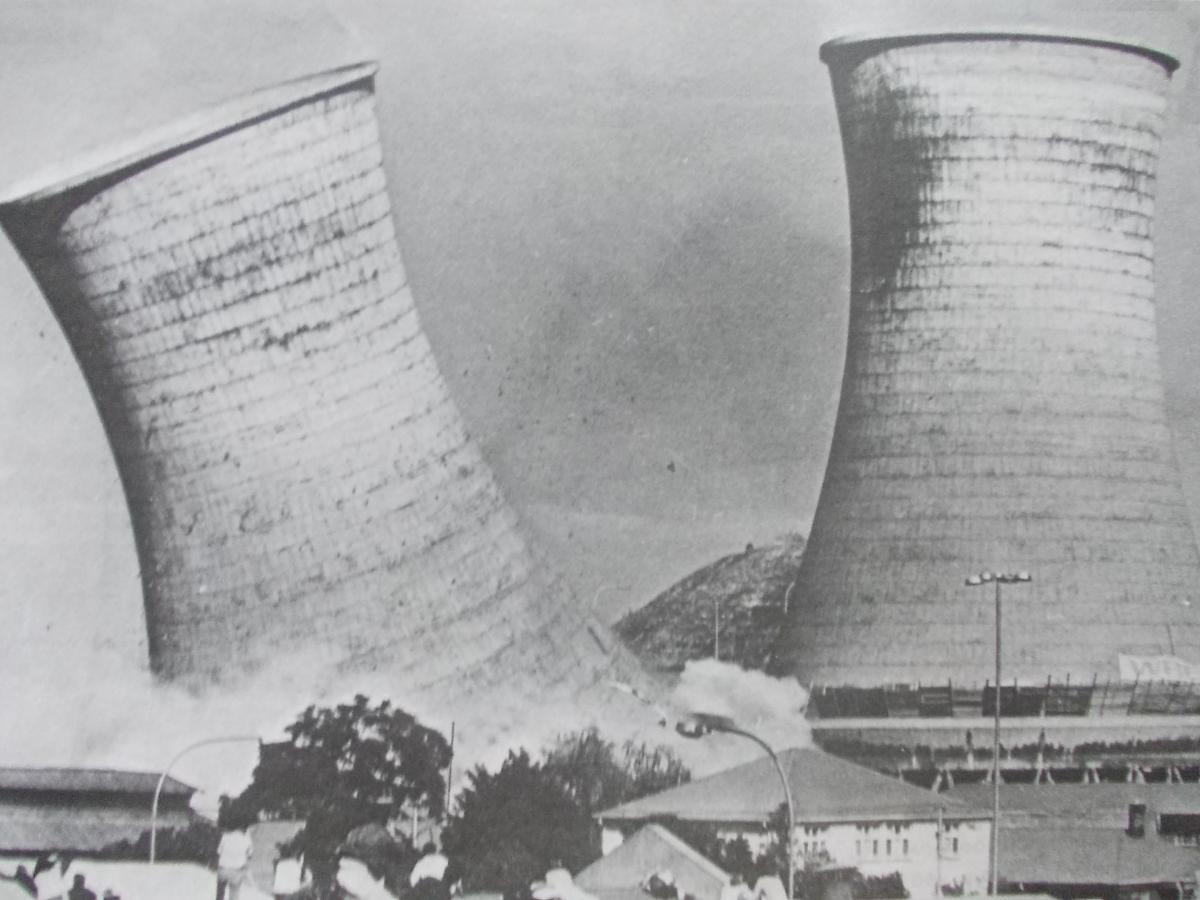

Demand for electricity in Johannesburg continued to outstrip supply and other power stations had to be built. In 1947, the Orlando Power Station was commissioned and then completed by 1955. After this, the Kelvin A Power Station was opened in 1957 and Kelvin B in 1964, in Kempton Park. These are still in operation and are privately owned. The Jeppe Street Power Station was closed in 1961, but then revamped with two Rolls Royce gas turbines for emergency use, but finally closed in the 1972. The four cooling towers were demolished in 1985 accompanied by much protest from the heritage community.

Orlando Power Station (Bath Family Archive)

Demolition of the cooling towers

In the three photographs below by Ken Bath, the Braamfontein Coal Stage is the vast structure on the left hand side of the photographs. Steam train engines would have been driven in under the structure and coal supplied to the tenders via chutes. The views are looking west.

The Coaling Structures at the Braamfontein Locomotive Depot (Bath Family Archive)

Thank you to Les Pivnic for his contributions to the accuracy of this article.

Sue Taylor biography - Sue Taylor holds a PhD in Plant Biotechnology from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Her current interests encompass cities and urban greening, material culture (and what trash can tell us about society), degraded peripheries and researching the disintegration (and rehabilitation) of landscapes, railways and buildings. She has recently concluded a three year writing contract as a Research Fellow at the Afromontane Research Unit, QwaQwa, University of Free State (South Africa).

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.