Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

My father was not a famous musician nor did he raise extraordinarily talented musical children. However, he did give all of his three children an appreciation for music and the arts.

When I was a child, growing up in a family of five, including my parents, my older brother and my twin brother, music was a constant in our home at 12 Pitso Street in Atteridgeville.

Most weekdays, my father David "Fighter" Moloantoa would be away on work business. He was a career marketer, sales representative and businessman.

In the 1980's, during his heydays as a sales representative, he introduced many new products and services to the black township market all over South Africa and beyond. These products included well-known household brands such as Colgate tooth paste, Badedas bath soap and many others.

Over weekends when he was home, the family would be treated to the music that he'd discovered while he was away. I can recall him bringing new music records, called LPs from his red Ford Cortina and playing them on the record player in our dining room.

Diana Ross and the Supremes, Quincy Jones and his "We Are The World" ensemble, Miles Davis and The Union of South Africa are some of the music albums that would be on heavy rotation in our household all weekend long.

Aside from his own record collection, my father shared his love for music with some of his neighbourhood friends. Most of them were into jazz.

Bra Boykie, who lived in the house across the street from us, lived for jazz music. On Sunday mornings, way before the birds could chirp the new day in, he'd open his front door and blow his trumpet with a sweet jazz melody to wake the neighborhood up.

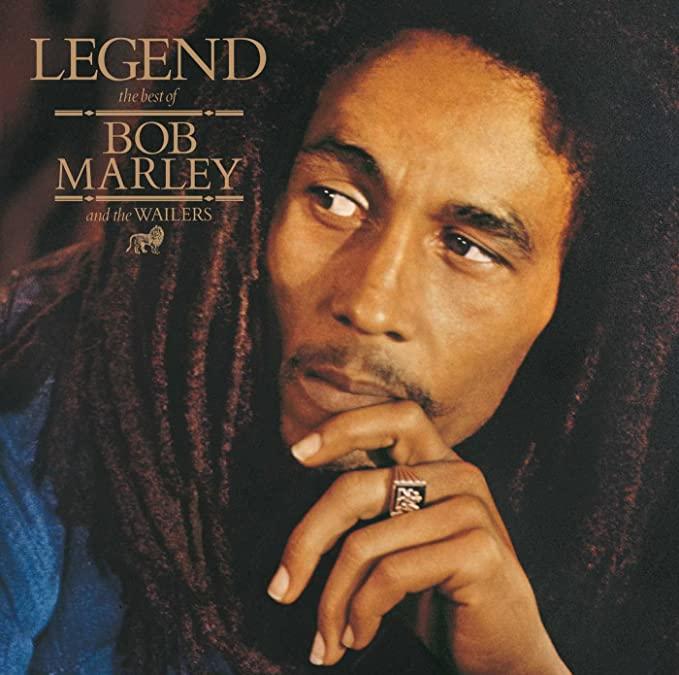

The first music album that my father bought for his children was for my twin brother, Thapelo. He'd fallen in love with reggae music, and he'd asked my father to buy him a reggae music album. He obliged. On one of his trips, he brought home with him the classic reggae music album Legend, by Bob Marley and the Wailers.

Album cover

Prior to his marketing and business career, Bra Fighter, as he was nicknamed amongst his peers, had been a music promoter.

In the early 1960's, he organized and promoted music shows in Attredgville and in the other townships of Pretoria. He brought the big national music stars from Johannesburg to the township halls of Pretoria.

The Jazz Epistles, The Manhattan Brothers, The Mahotella Queens, Koppie Moeketsi and the Cuban Brothers are some of the music acts that he roped in to perform at his gigs.

Album cover

This is how he got to personally know some of the artists in those bands. Because the bands would usually spend the night at our Atteridgeville home right after each gig.

Whenever we held a discussion about his days in "showbiz", as he called his music promotion days, he'd refer to some of the music artists by their nicknames. Hugh Masekela was "Makweru", and Caiphus Semenya was "Katse".

When he started his first formal job, as a salesman at Ellerines Furnitures on Schubart Street in downtown Pretoria, he had the brilliant idea to use his music show promotions experience as a marketing tool for his new job.

He convinced his bosses at Ellerines Furnitures to sponsor music shows. He would then attend the shows and distribute Ellerines Furnitures promotional leaflets and other marketing materials at the shows. Ellerines Furnitures received a big boost in their sales due to this exercise.

In the mid-1980's, during the height of the struggle against apartheid, certain music artists and their songs were banned from airplay by the Censorship Board of the Nationalist Party government.

This was music deemed to be "incisive" and "troublesome" and aimed to overthrow the apartheid state. Music by exiled South African music artists such as Hugh Masekela, Marriam Makeba, Jonas Gwangwa and others fell under this category.

As an underground operative in the struggle against apartheid, my father gained access to this music through his fellow underground operatives. Whenever he visited Botswana or Swaziland on work business, he'd bring back some banned records or videos. After listening to them for a while, he'd pass them onto his fellow activists, with the stern agreement that if caught, they'd not reveal the source of the music.

During the 1970's, even though he was a travelling marketer, he continued to promote music shows. He'd recognized a niche in the market for staging music shows in the far-flung areas of South Africa, where music fans hardly ever saw their favourite music artists on stage.

Amongst the artists he went on the road with for these shows was a still-unknown and upcoming reggae music artist.

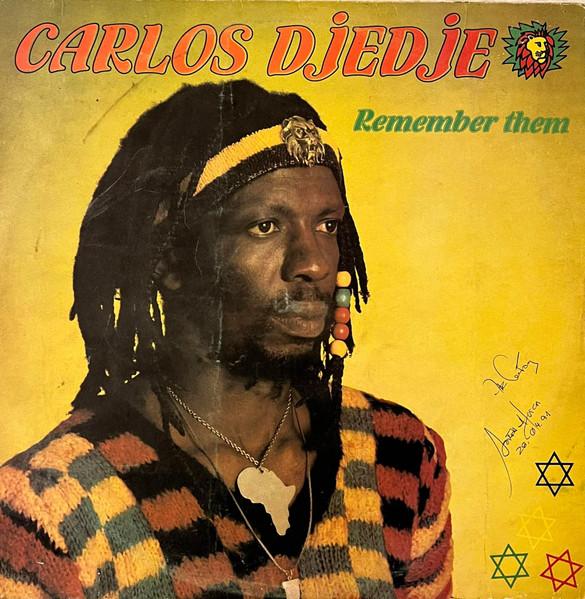

Carlos Djedje, born and raised in Atteridgeville, later became a famous reggae music artist. He released a number of reggae music albums, some of whose songs were banned by the apartheid state.

He is credited with starting the reggae music movement in South Africa, way before Lucky Dube arrived on the local music scene.

Album cover

Today Djedje is a senior director in the Department of Arts, Sports and Culture in the City of Tshwane. He is often referred to as "the father of South African reggae." In turn he returns the credit to his first music promoter, Bra Fighter.

Fast-forward to the new South Africa, music still formed a big part of my father's life. The early 1990's was a time of new hope, a time for revival and a time for celebration in South Africa. Apartheid was on the way out, and the promise of a new beginning lay in the horizon.

The jubilant spirit in the air was punctuated by music. Music by the band Sankomota, Paul Simon and his Graceland project and the music previously outlawed by the apartheid government was blasting through sound systems and radio stations all over the country, least of all in my father's blue Toyota Cressida.

Album cover

It was a good feeling to watch him sing along to music that he would instantly be arrested for having just a few years before.

Marriam Makeba's "Aluta Continua", Hugh Masekela's 'Bring Him Back Home (Mandela) and "It's Wrong (Apartheid) by Stevie Wonder topped my father's playlist at home and in his car.

He took us to some music shows. The one show that I can clearly remember is the musical poetry show by protest poet Mzwakhe Mbuli. It was in downtown Johannesburg, at the Market Theatre. Even though apartheid was on the way out, his poetry still carried a message.

Market Theatre (The Heritage Portal)

In the last few years of his life, I spent a lot of time in discussion with my father. We'd talk about everything, from politics, world affairs, the economy and of course, music.

I'll never forget the day when I returned from a music journalism seminar, a part of the Cape Town International Jazz Festival in Cape Town, and told him that I'd met one of his favourite American jazz music pianists Dave Brubeck and his jazz artist sons.

The look on his face told a story. A story of joy and of long-awaited contentment. Finally, it seems as if he was saying to himself, the connection has been cemented. The musical baton has been passed. I've completed the mission.

Soon after his passing, we as a family had a discussion about his life. Like everybody else who knew him, we all agreed that he loved his family first, and his work. But then, we came to one other realization. That more than anything besides his family, our father appreciated and truly loved music.

Main photo: David "Fighter" Moloantoa, the ever-cheerful music lover (top). Daluxolo Moloantoa and Thapelo Moloantoa with jazz legend Hugh Masekela, a friend to their father (bottom).

About the author: Daluxolo Moloantoa is a freelance writer and journalist. After being awarded a scholarship by the Sowetan newspaper and Herdbuoys McCann-Erickson advertising agency he studied copywriting at the AAA School of Advertising in Johannesburg. After a brief period working in the advertising industry, he went on an exchange programme to England and studied for a Community Media Certificate with the Community Volunteer Service Media Clubhouse in Suffolk. He became an arts journalist with Ipswich-based youth magazine IP1 and began covering South African arts-based news for London-based South African publication The South African as well as Cape Town charity magazine The Big Issue. On his return to South Africa he became arts contributor to a number of local publications. In 2015 he won the Academic and Non-Fiction Association of South Africa (ANFASA) – Norwegian Foreign Fund Writers Award for his research project on missionary schools in South Africa. Click here to see more of his work.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.