Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Much has been written about the concept of discarded or “found” photographs. These photographs often contain the most surprising themes which continue making significant contributions to a broader visual and historical perspective.

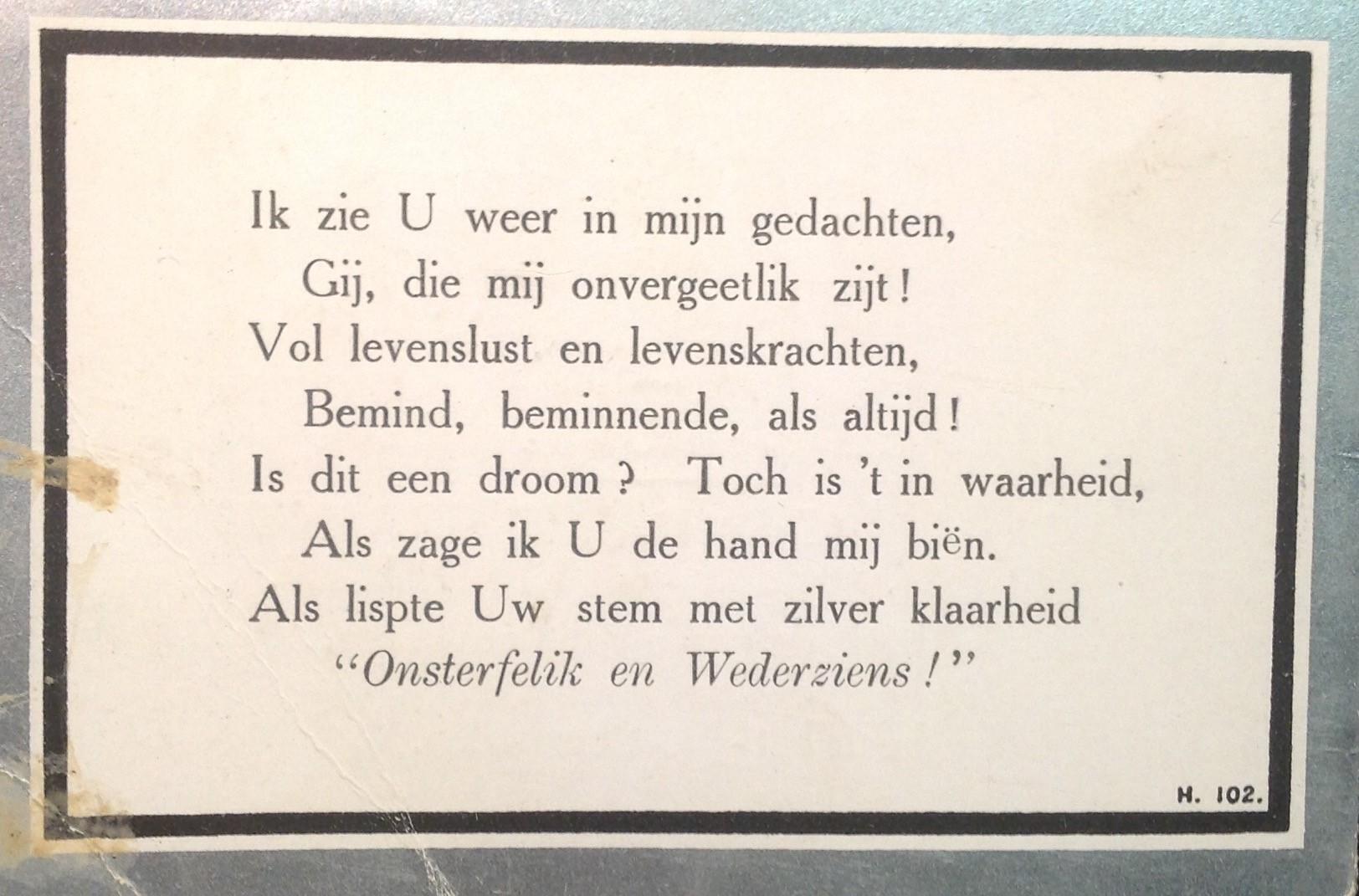

Whilst the possible themes of found photographs vary broadly, the primary theme remains around our experiences of the world – our memory of something captured - including our own emotion around the commemoration of the dead.

Occasionally these discarded or “found” photographs also include the almost taboo category of mourning photographs or “In Memoriam” photographs.

The Latin “In Memoriam” translates into “In memory of” or “as a memorial to”.

Examples of front cover of antique “In Memoriam” cards. These cards have become of significant interest to researchers and should therefore be curated instead of being discarded or destroyed.

During the mid-1800’s to early 1900’s, photography played a vital role in capturing images of loved ones, not only whilst alive, but also at the time of their death.

Think about it – A photograph turns the past into an object of tender regard (Sontag, 2002), but also only where we can relate to the actual image or memory portrayed.

This therefore confirms the intent of memorial photographs – it is to memorialise the departed whilst at the same time it forms a remembrance of our own grief – the photograph in other words becomes a keepsake to remember the deceased.

The intent with this brief article, albeit from a Eurocentric perspective, is to present the role that the photograph played in the mourning process more than a century ago. Whilst the primary focus of this article is on South African mourning photographs, it is acknowledged that the theme applies internationally.

Whilst some may view mourning photographs as a morbid topic, the reality is that it forms part of our human journey. It is simply another aspect of documenting our realities. Even today many of us have the need to commemorate loved ones we have outlived.

To mourn is a natural human emotion. Mourning the loss of someone (or a pet) is associated with the loss that follows after a bond or affection has formed with that individual. As humans we all mourn differently – so do cultures. Some animals, such as primates, whales, dolphins and even elephants have also been recorded to mourn.

The mourning process is bound up in a complex web of social norms. The way we experience a loved ones’ death, or express our feelings of loss, are governed by complicated patterns of mutual expectations grounded in social norms (Colombo, 2016).

During the Victorian era (category within which many of the photographs included in this article fall into) various superstitions existed following the death of a loved one. Some of these superstitions included for example drawing of curtains, stopping all clocks in the house, covering of mirrors etc.

Whilst much has been written on Post-mortem Photography (photograph taken of the dead), little has been written about the significance of photography during the broader mourning process.

It is suggested that surviving mourning photographs from more than a century ago are not that common, at least not in South Africa. This is probably also due to the perceived morbid nature of the topic that surviving family members would rather discard any such imagery.

Death, or more specifically images of the dead, remind us of our own mortality or the inevitability thereof (Momento Mori = Reminder of deaths’ inevitability), or put differently, contributes to our appreciation of the gift of life.

Mourning photographs are not limited to the better-known theme of Post-mortem Photography. Although the words post-mortem and memorial photography are often used interchangeably when referring to photos taken of the dead, post-mortem photographs relates to images taken of individuals after they have passed away, whereas memorial photographs (inclusive of post-mortem photographs) includes a broader spectrum of mourning photographs containing photographs of the deceased when they were still alive or even showing surviving family in mourning.

The use of photographs as it relates to mourning can therefore be divided into four distinct categories, namely:

- Post-mortem photographs

- Funeral Notices containing actual photographs of the deceased

- “In Memoriam” photographs (other than funeral notices)

- Surviving family members in mourning

The primary theme is on the latter 3 categories in that much has been published on Post-mortem Photography - probably because of the underlying human curiosity around the theme linked to the possible shock value portrayed by such images.

Below a short analysis on each of the topics cited above with some photographic examples included:

Post-mortem photography

Post-mortem photography, a practice that peaked in popularity around the end of the 19th century, has faded into history in that the portrayal of such images became stigmatised due to them increasingly being perceived as macabre and sensationalistic, whilst memorial photography is still in use today.

Whilst photographs produced of the dead by police or during pathology related work may also be described as post-mortem photographs, their intent is not to memorialise the individual that passed away.

During a presentation to a historical society on the topic of Post-mortem Photography, where some images of the dead were visually presented to the audience, the author enquired with the audience as to what their experience was seeing such imagery. Not a single negative response was received. The underlying response was that photographers of that era clearly attempted to produce a dignified image – showing the dead peacefully asleep.

See the author’s earlier article published on South African Post-mortem Photography here.

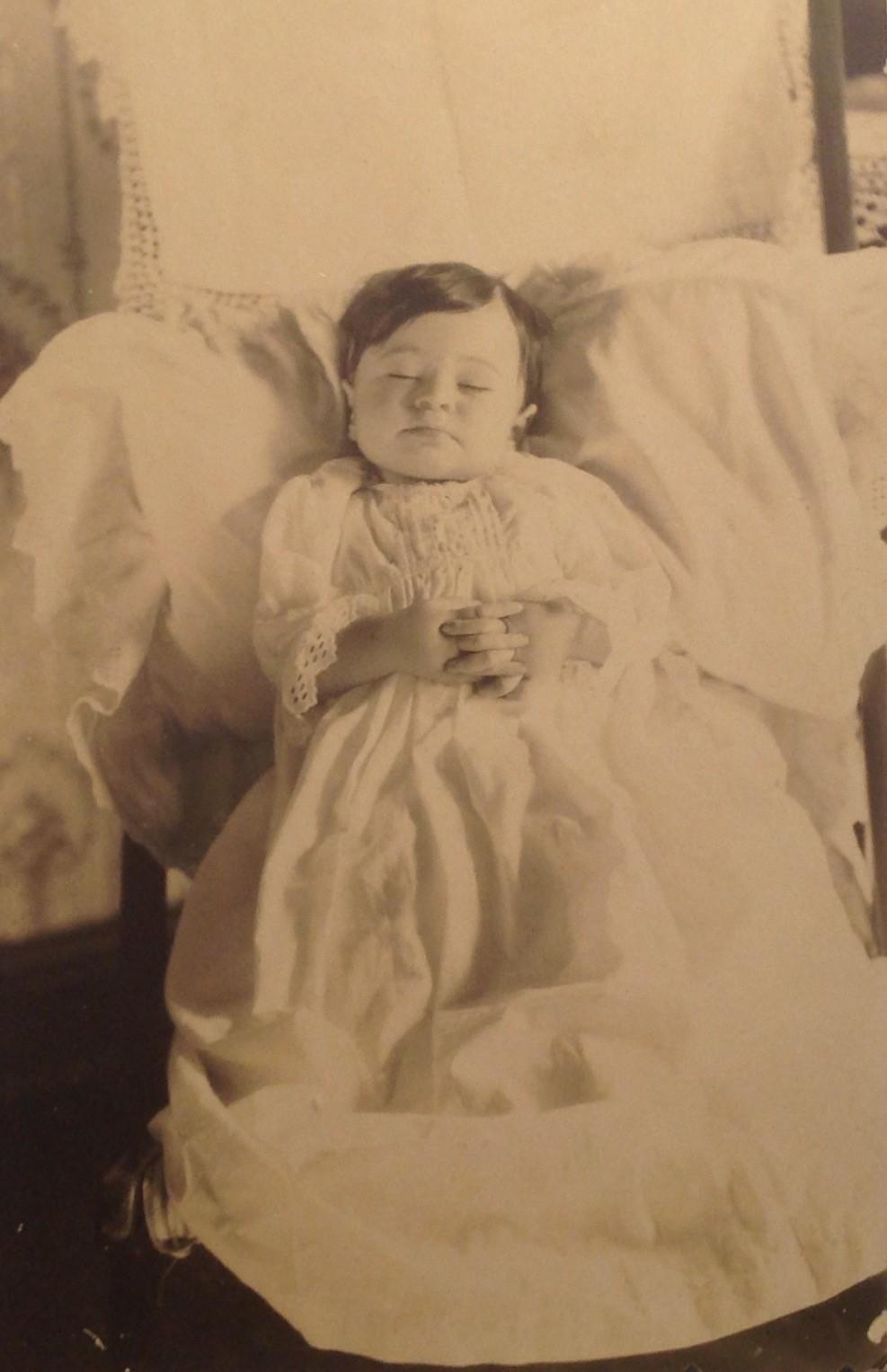

Postmortem photograph of an unknown young girl (Circa 1918). The unknown photographer made special effort to capture an image of the girl, peacefully “asleep” with her hands and fingers interlocked. This in itself is a rather unusual pose for a child when alive. Considering that the photograph has been produced in a postcard format, the same image may have been printed in multiples. This means that this very same image may still surface from a family photograph album or two.

Funeral notices containing actual photographs

More than a century ago, unlike today, it was not a common practise to have actual photographs included on a funeral notice – more so prior to the 1880s, therefore making any such finds even more significant.

The reason for this is three-fold:

- It would have been more costly to produce such cards in multiples containing an original photograph;

- Surviving family members would first had to identify which photographer may have captured an image of the deceased before and then in turn approach the photographer enquiring whether he still had the glass negative containing the image of the deceased in order to reproduce a number of copies to paste into the funeral card;

- Alternatively, there was an existing Carte-de-Visite or Cabinet Card format photograph from which the family would then have requested the photographer to reproduce an image from.

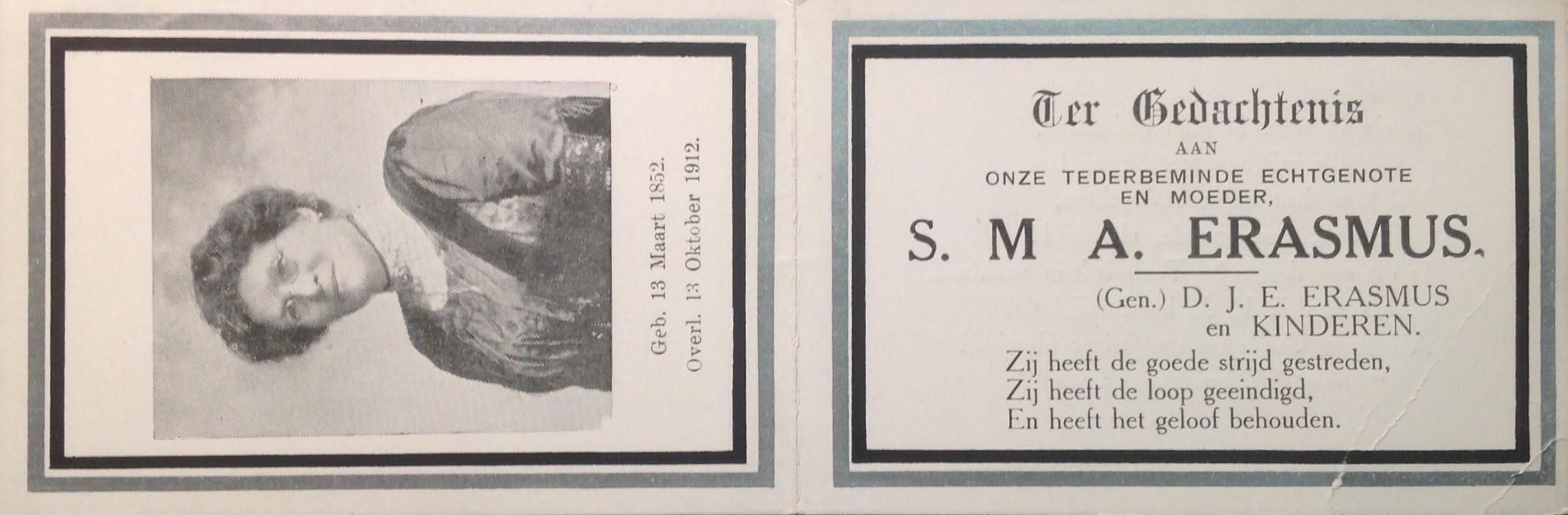

The emphasis here is on an actual photograph pasted onto a card and not a photograph that became imprinted (scanned) onto a card. Imprinted images seem to have appeared as early as the 1910s.

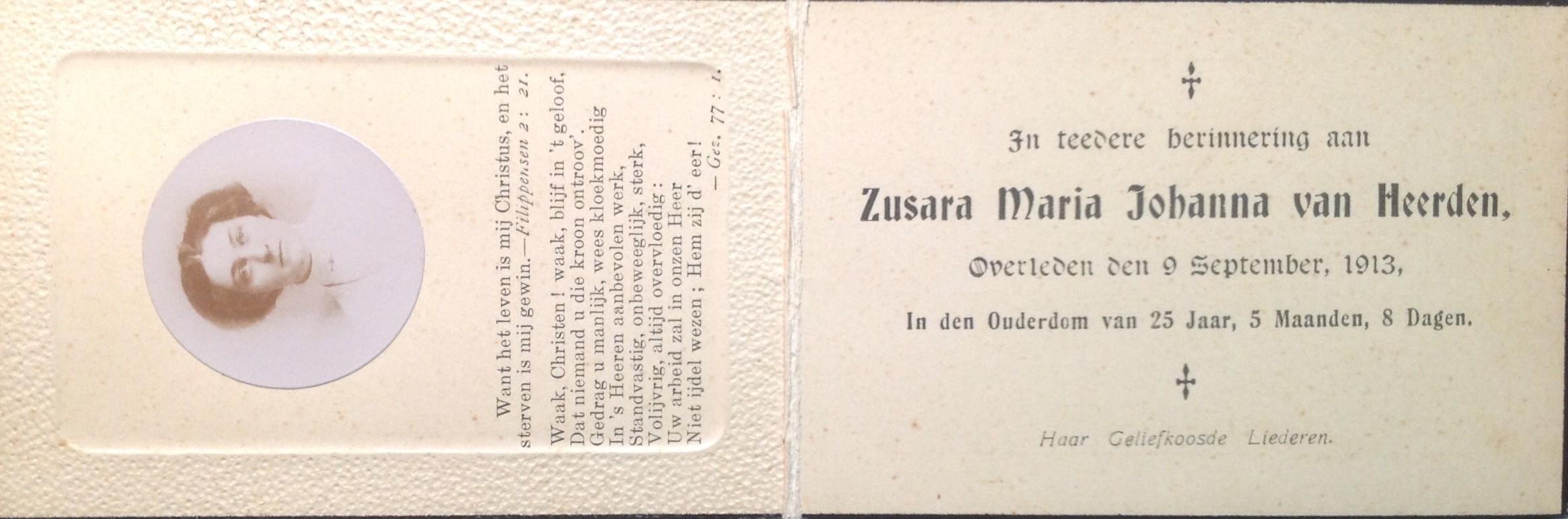

Funeral cards commonly appeared as two thick paper pieces folded together. This has resulted in some funeral cards therefore being incomplete in that the parts have become separated (torn) over the years.

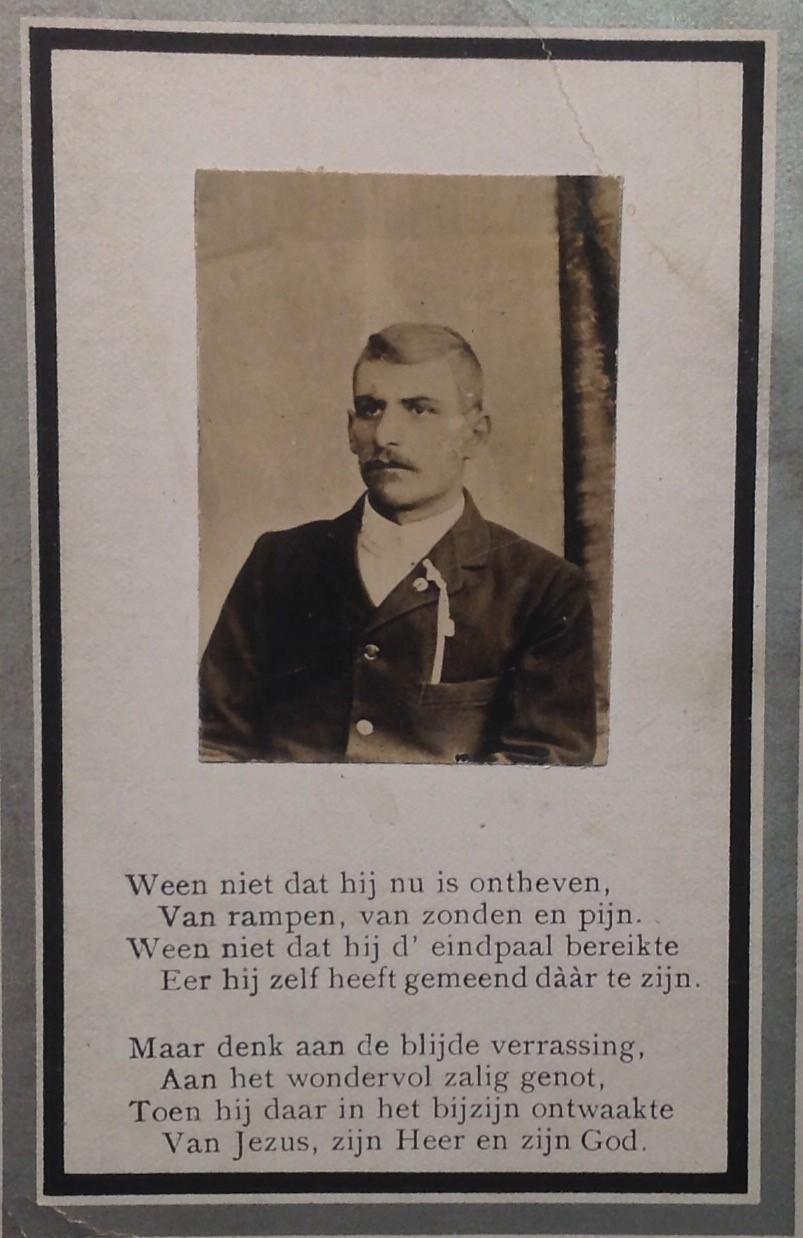

Two funeral notices with actual photographs pasted onto the cards. In both instances the deceased are unknown in that the cards are incomplete. Funeral notices were usually presented in a folded format. Occasionally the parts have torn apart resulting in incomplete pieces as presented here.

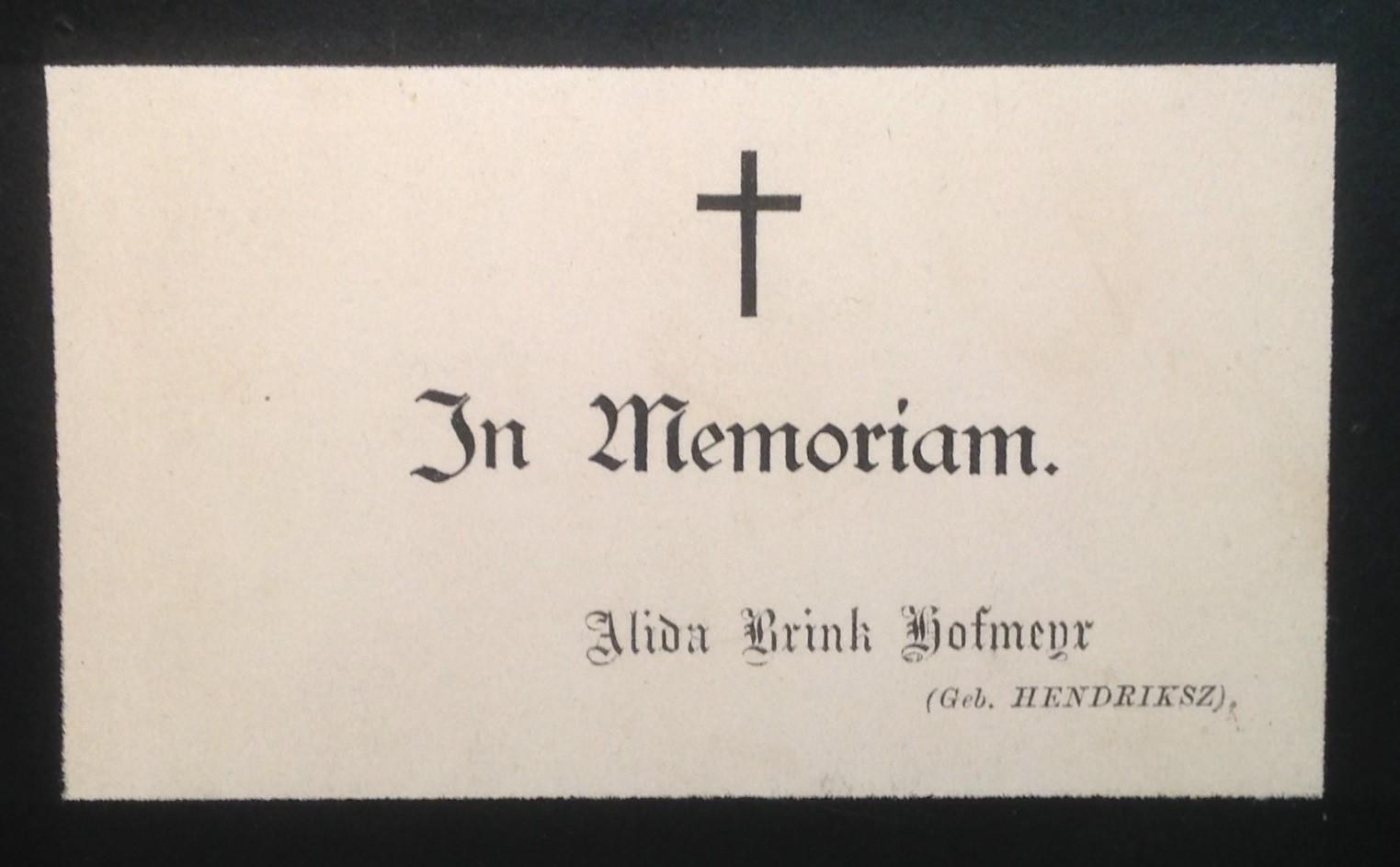

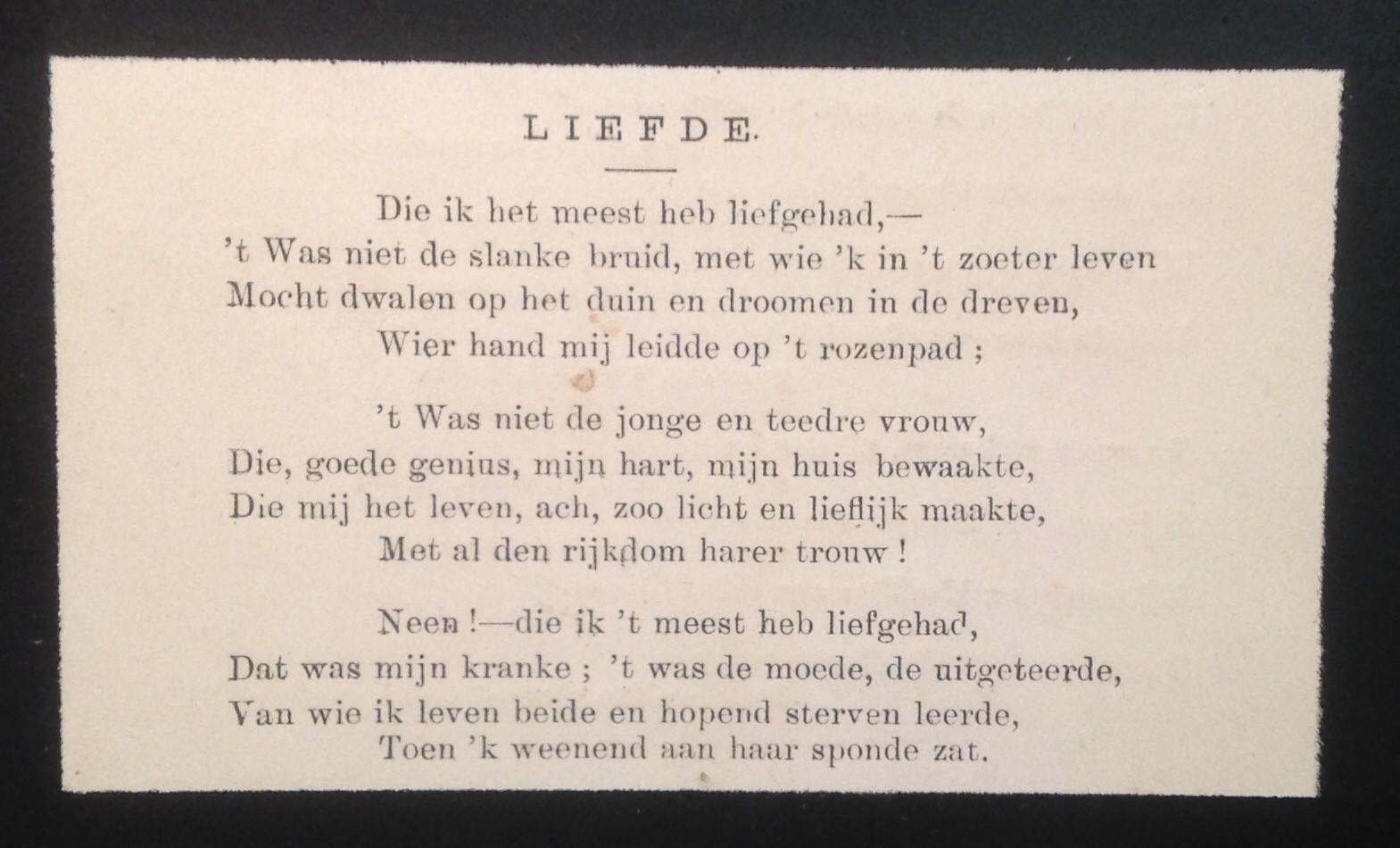

Funeral notice for Alida Brink Hofmeyr (nee Hendriksz) born in Somerset West on 12 October 1846 and passed away aged 27 in Cape Town on 12 December 1883. She married Jan Hendrik Hofmeyr (“Onze Jan”) on 17 August 1880. After her death, Jan Hendrik married her younger sister Maria Cornelia. The poem in Dutch titled “Love” clearly was penned by her grieving husband.

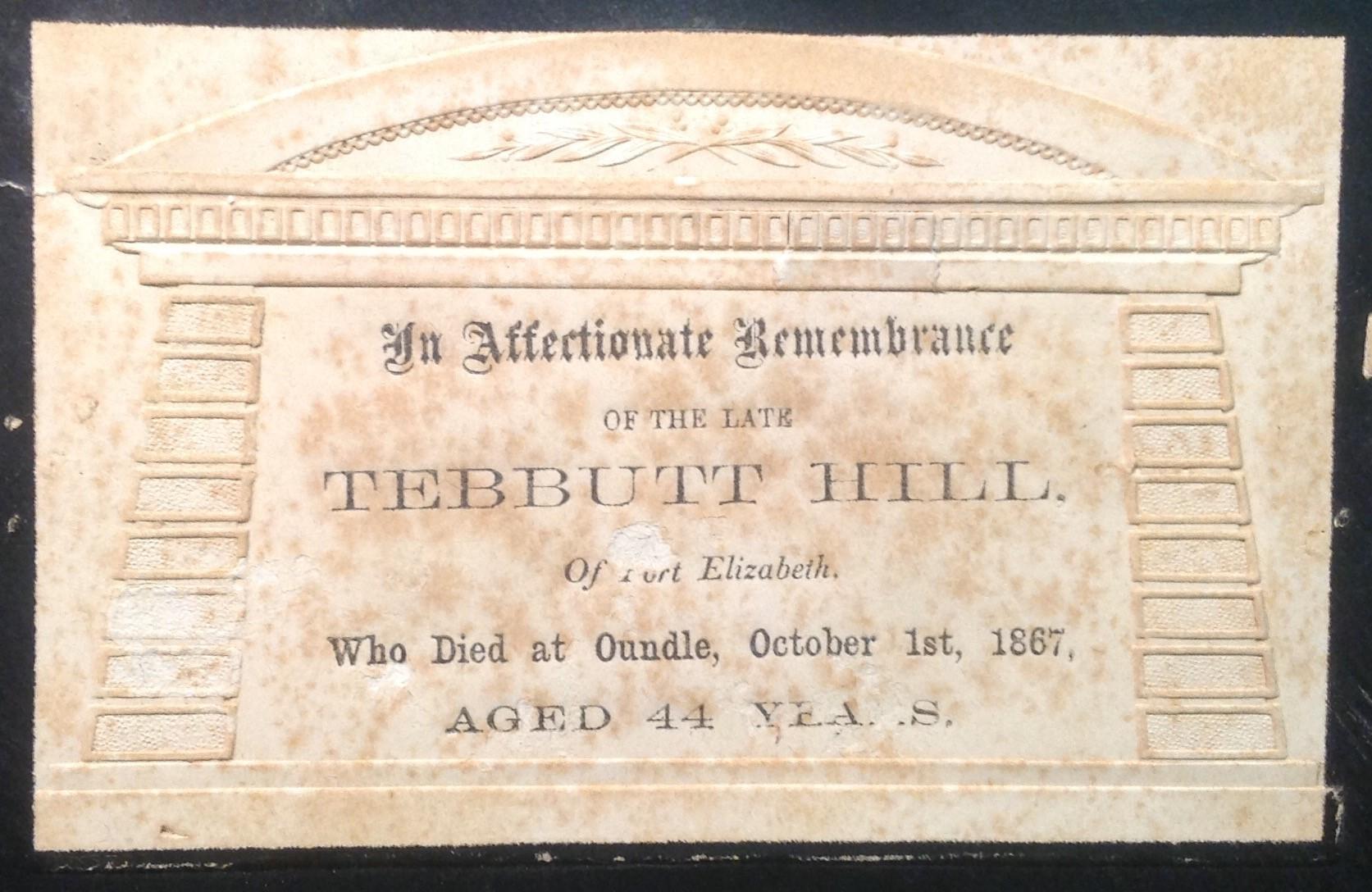

An unusual funeral notice which contains a slot (just above the two pillars) for a Carte de Visite photograph to be slipped into. Tebbutt Hill was born in Northamptonshire during 1823 where he also passed away on 1 October 1867. Of significance is that during around 1852 he was based in Port Elizabeth where he married Mary Maria Muirell. The couple had 8 children. One of their sons was also named Tebbutt Hill.

Example of Funeral notice with imprinted image. This is therefore not an original image pasted onto the card. Of interest is that imprinted images were in use from as early as 1910s onwards. Sybella Margaretha Aletta Erasmus (born Schabort) was the second wife to General Daniel Jacobus Elardus Erasmus (Maroela) who was involved in the 1st Anglo-Boer War as well as the Jameson Raid defeat.

Funeral notice of Susara Maria Johanna van Heerden. She was born during 1888 and passed away during 1913 (aged 25). Her parent seem to originate from Cradock in the Eastern Cape. Funeral cards often contained personal poems or religious quotations. This poem is in Dutch.

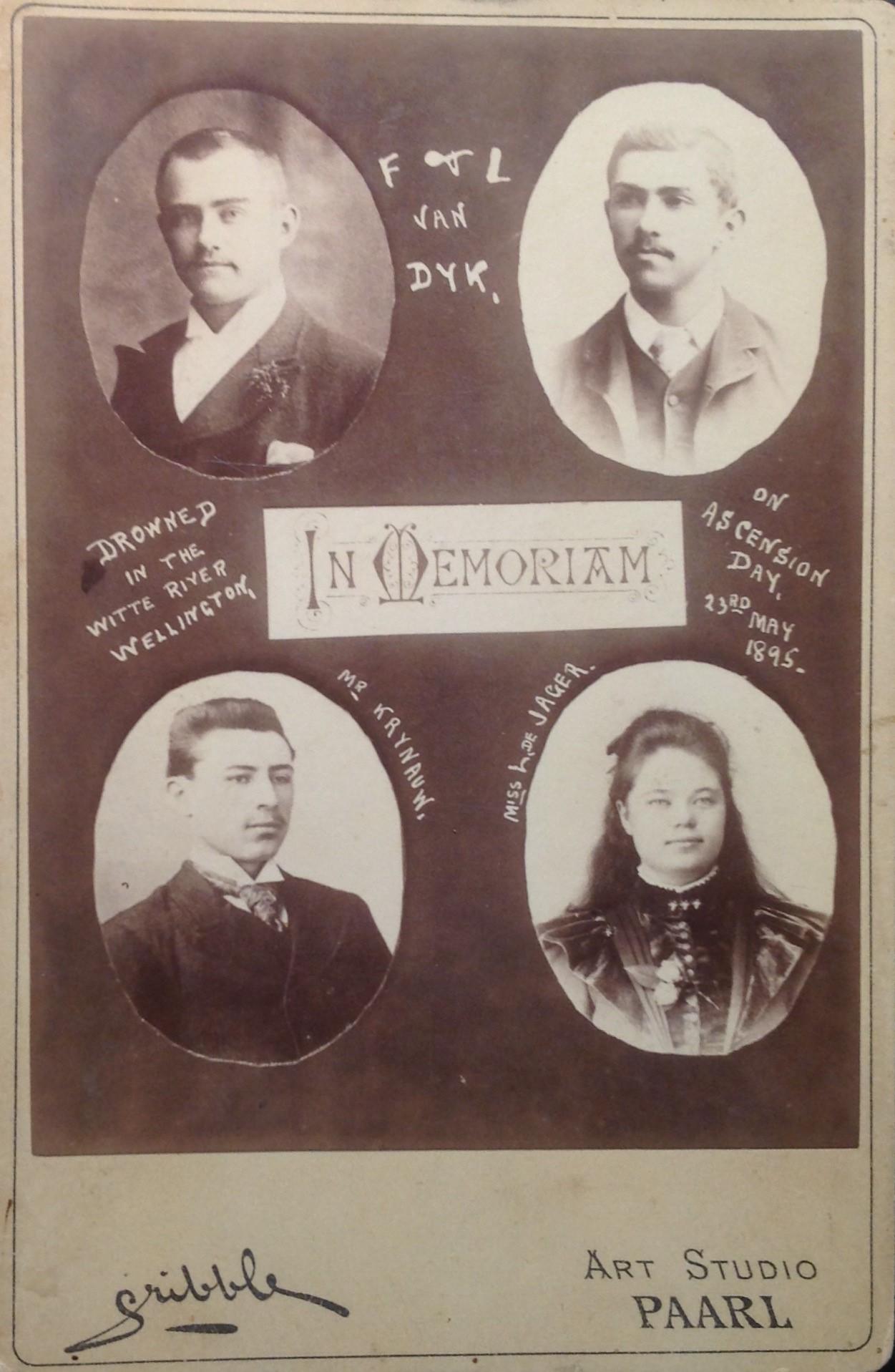

“In Memoriam” photographs

These photographs are not directly linked to the funeral process. They have typically been produced post the passing of the loved one for potential distribution amongst family members or the broader population where the death may relate to a person of significance.

One classical example of a historical photograph that may fall into this category is a photograph of the Prince Imperial who was killed during 1879 in the Zulu War. After his death, some photographers saw a commercial opportunity in reproducing images in multitudes that they may have captured of him prior to his death.

Another common method of remembering a loved one was to mount a photograph into a mourning brooch or pendant. Men and women would wear such jewellery confirming their connection to a deceased family member.

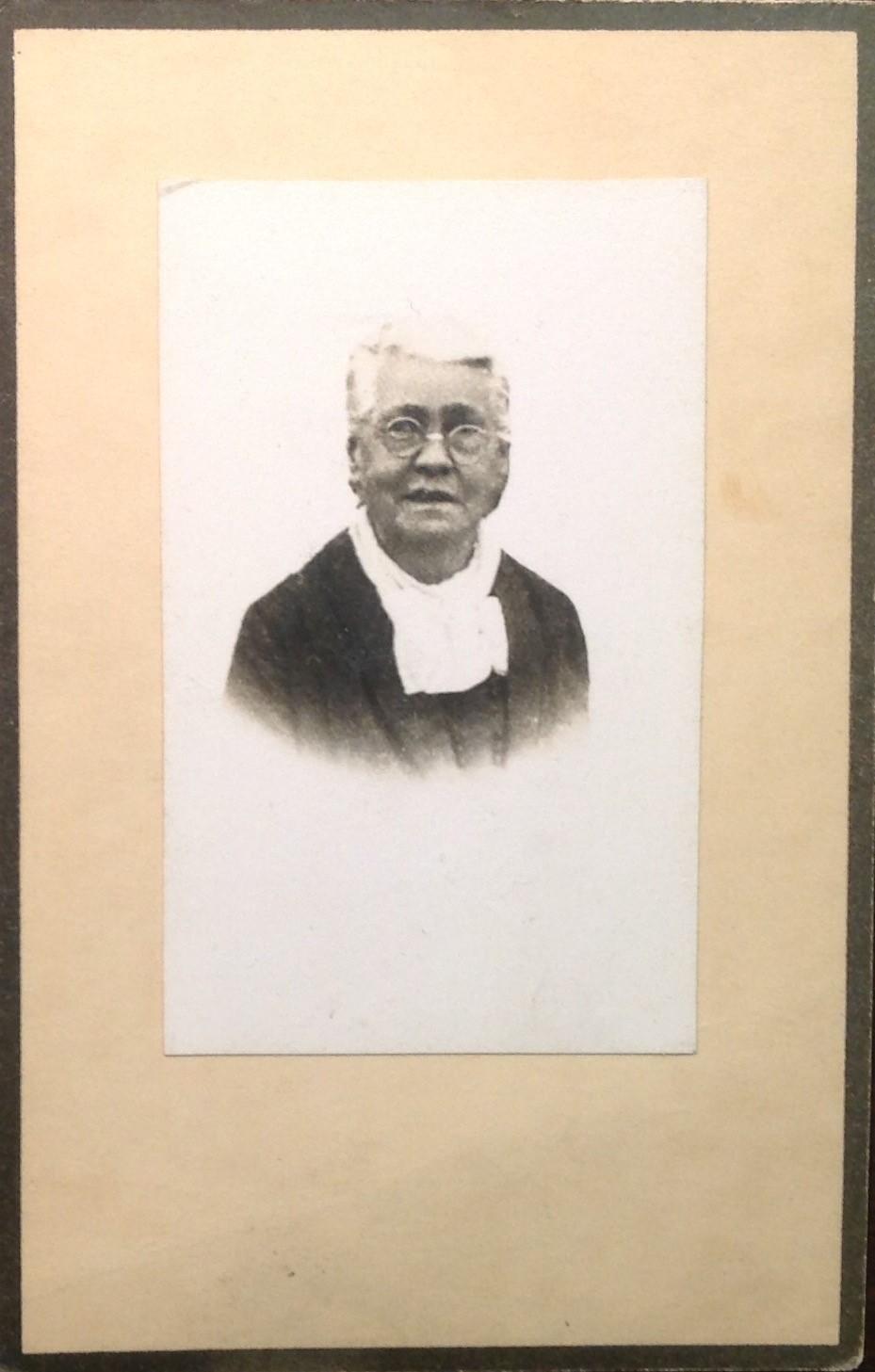

A Cabinet Card format photograph by Cape Town based James Watson & Coy of an unknown lady (Circa 1895). The significance of this image is that she is seen wearing a brooch which in all probability contains a photograph of a loved one that passed away. Mourning jewellery was prevalent in the Victorian/Edwardian era. Photographs were contained in either pendants or brooches.

A photograph of an unknown young girl mounted in a mourning brooch. The back of the brooch contains a strand of hair of the young girl.

Cabinet Card format Memoriam photograph by Paarl based photographer James Gribble following the tragic Wit River drownings on 23 May 1895. Gribble in all probability would have photographed the 4 young people before which assisted him in putting this unusual collage together. The 4 young people were attached to the Wellington based Hugenote College at the time of their death. A memorial has been erected on the Wit River in Bainskloof in memory of the 4 young people. They were the two brothers Lourens Charl van Dyk (aged 23 at the time) and Francois Johannes van Dyk (aged 21 at the time), Christiaan Krynauw (19 years old at the time) and 18 year old Lettie de Jager.

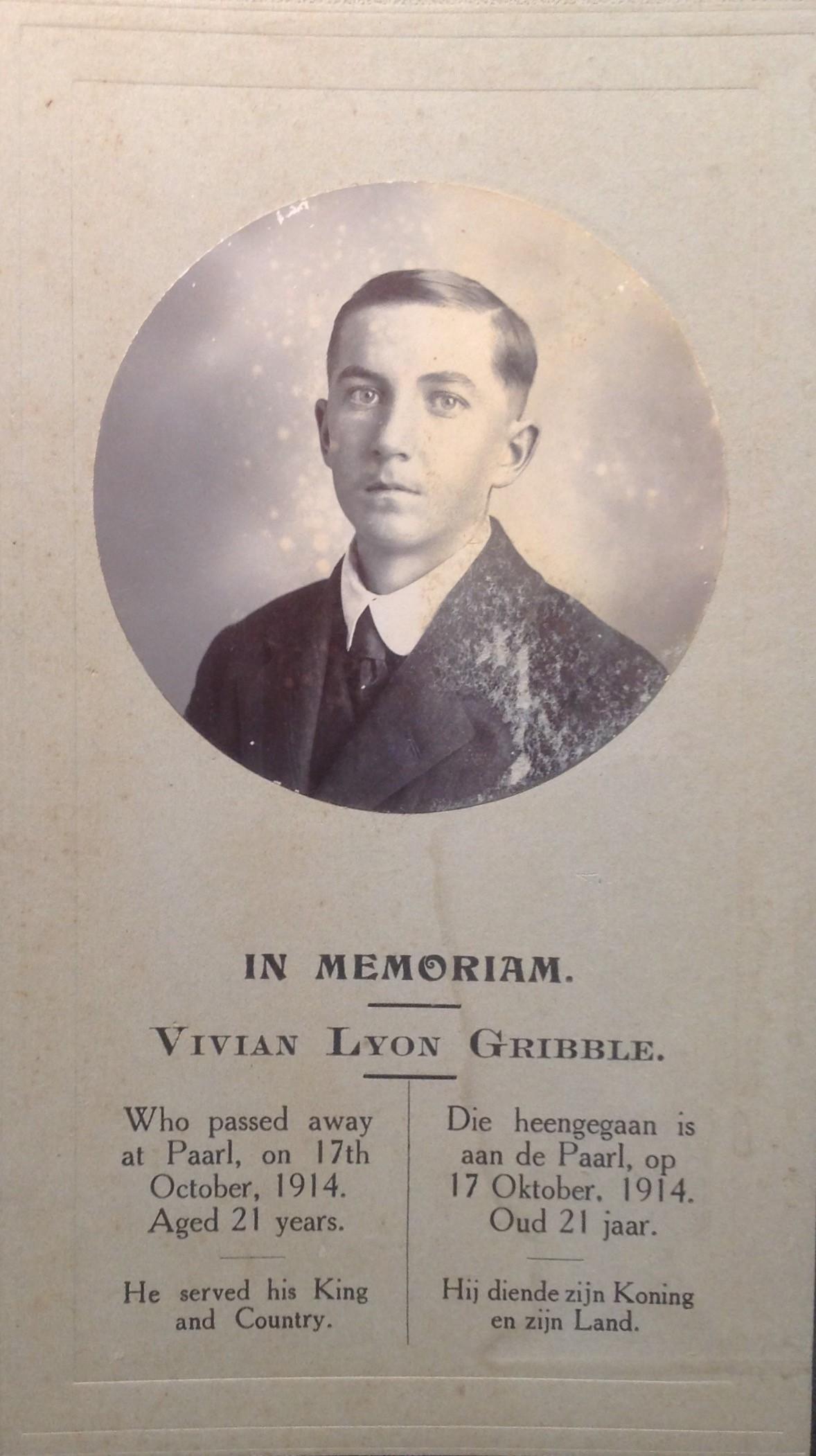

A Memoriam card (slightly larger than a Cabinet Card) of Vivian Lyon Gribble who passed away at the age of 21 following tuberculosis. His father was the well-known Paarl based photographer James Gribble who would have captured this photograph of his son and would probably have produced at least a dozen of these cards.

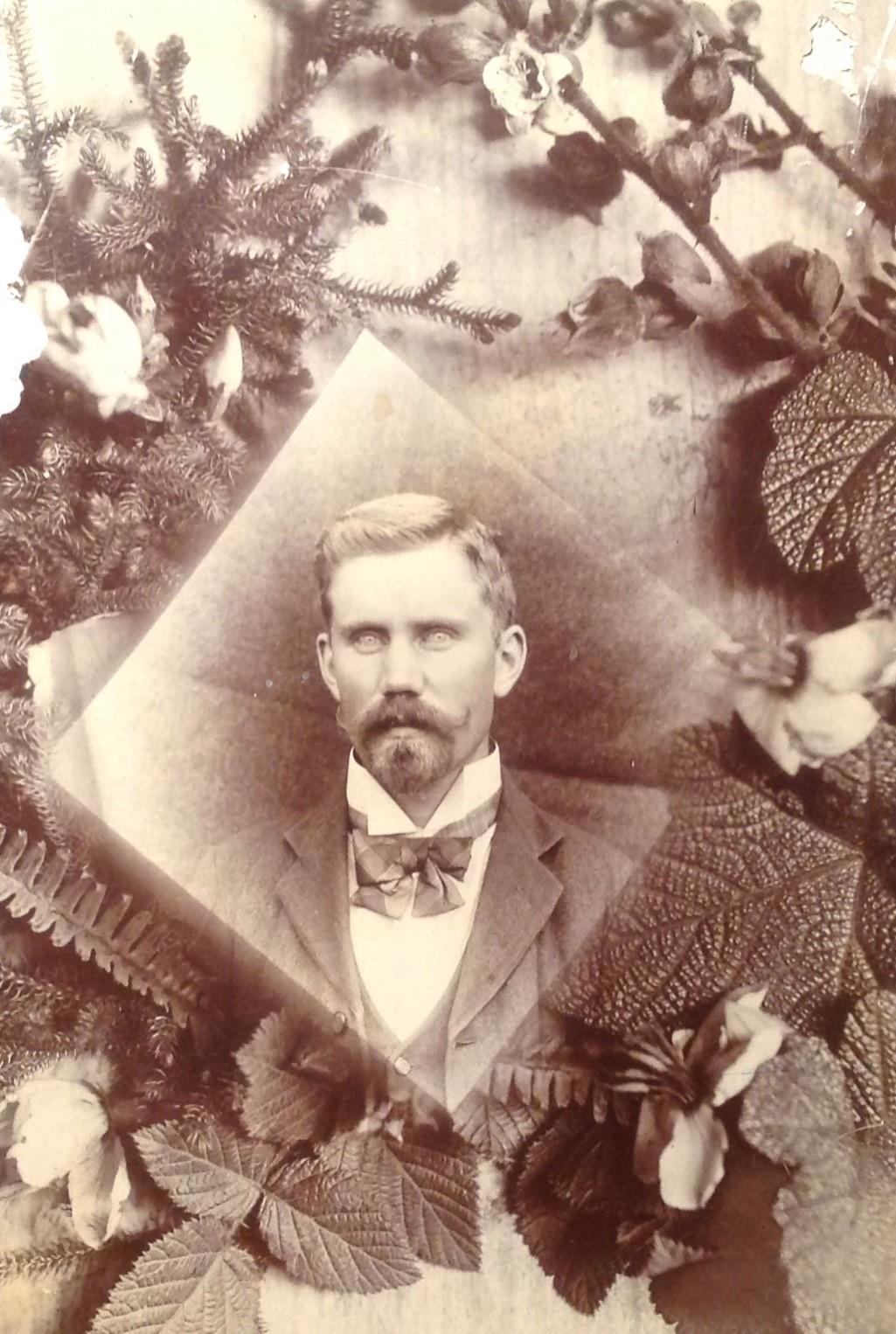

A Cabinet Card format collage photograph of an unknown male by unknown photographer (Circa 1900). The flowers and leaves photographed on a wooden background may have been placed on the coffin of the gentleman in the image.

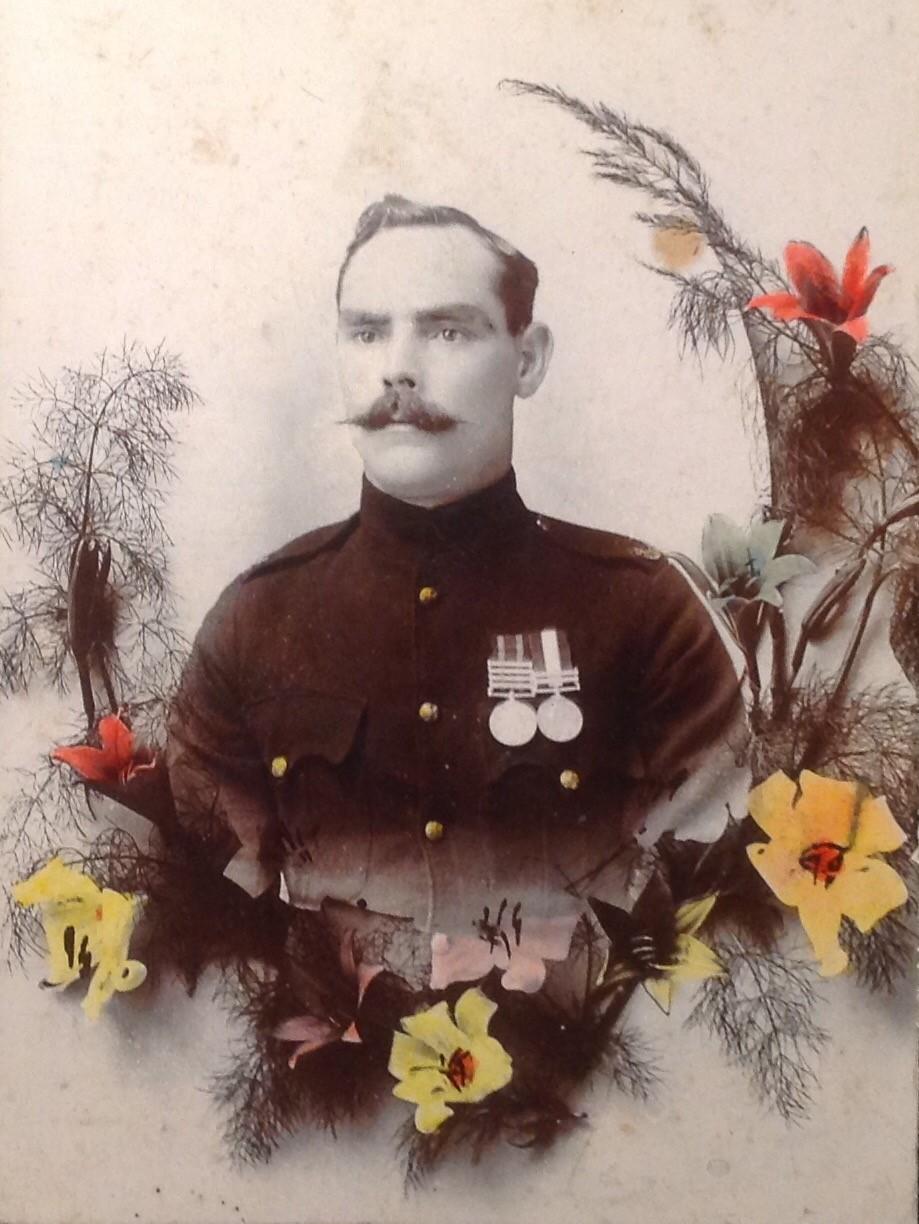

A hand coloured Cabinet Card format mourning photograph (circa 1902) of unknown Anglo-Boer war soldier who may have fallen on South African soil during the war. Photographer is also not known.

Surviving family members in mourning

This is probably the less obvious of the four categories as it relates to mourning and may occasionally result in some images being missed as a photograph relating to mourning or alternatively result in an incorrect assumption being made that the photograph relates to an individual in mourning.

This may include a person showing clear emotion of being in mourning or a person being photographed holding a photograph of a loved one.

A Cabinet Card format photograph by Philipstown based photographer JG Fourie of a young lady standing next to a framed photograph of either her brother or father who passed away (circa 1903). This may be an Anglo-Boer War related photograph.

Carte de Visite format mourning photograph showing a lady dressed in black (with black gloves) in a typical mourning pose.

Carte de Visite format mourning photograph by Cape Town based photographers Provost, Hodgson & Co from the Rykie van der Bijl album showing a lady standing with an image of either her husband or father (Circa 1875)

Exceptionally unusual mourning image in Carte de Visite format of an unknown lady holding a union case containing a photograph in her left hand. Union cases were manufactured from thermo plastic (Circa 1878). Also unusual in this image is the dog lying at her feet.

Closing

This misunderstood imagery provides anthropologists, historians and family researchers with rich information about not only mourning rituals and emotional responses to death, but also valuable genealogical data. Some of the information contained on the funeral notices included in this article may well be new evidence required by such researchers. Any historical memorial image therefore needs to be treasured as a historical artifact.

Photographic images curated in the Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection (HPRC), mainly represent a Eurocentric perspective. Future research or articles can also be constructed of the mourning process photographically captured from an Afrocentric perspective. It is however suggested that early black South Africans were less inclined to photograph a dead family or community member.

Although no South African photographs have been seen by the author of owners photographed with their dead pets, these certainly will also exist.

As a self-proclaimed South African photo historian, the author is also a registered psychologist with an interest in the broader human response to loss.

Main image: Unknown men standing at a coffin (Circa 1920). This photograph is indicative of our strong need to obtain photographs in memory of something. These men clearly wanted a memorial images of themselves with their family member/friend that passed away.

About the author: Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources

- Colombo, M. (2016). Animal grieving and human mourning. Animal Sentience 4(10) (www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org)

- Green, L.G. (1981). Beyond the City Lights - Witrivier Tragedy (pp 97-101) (vandykregister.com/histories)

- Hardijzer, C.H. (2017). Postmortem photography in South Africa. Theheritageportal.co.za

- Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection (HPRC). All photographs included in this article originate from the HPRC.

- Marix Evans, M. F. (2000). Encyclopedia of the Boer war 1899 - 1902 (www.sahistory.org.za)

- Sontag, S. (2002). On Photography. Penguin Books. London

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.