Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The iconic bright red double-decker bus is part of London’s “persona”, an instantly recognisable part of London life, however it would come as a surprise to many to know that on the outskirts of the capital, buses were once painted Lincoln Green. The reason for this goes back to before the Second World War, when the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB) was formed on the 1st July 1933.

Before getting into the nub of the piece - London buses, a little explanation of London’s prominence as a city is called for. London had been growing in size ever since the Great Fire of 1666, but unfortunately in the fire’s aftermath the city was rebuilt on the same plan it had before, due to property rights issues, thus the opportunity to town plan on a grid system (a la Paris) was missed for all time. This very fact would cause traffic congestion in the long term.

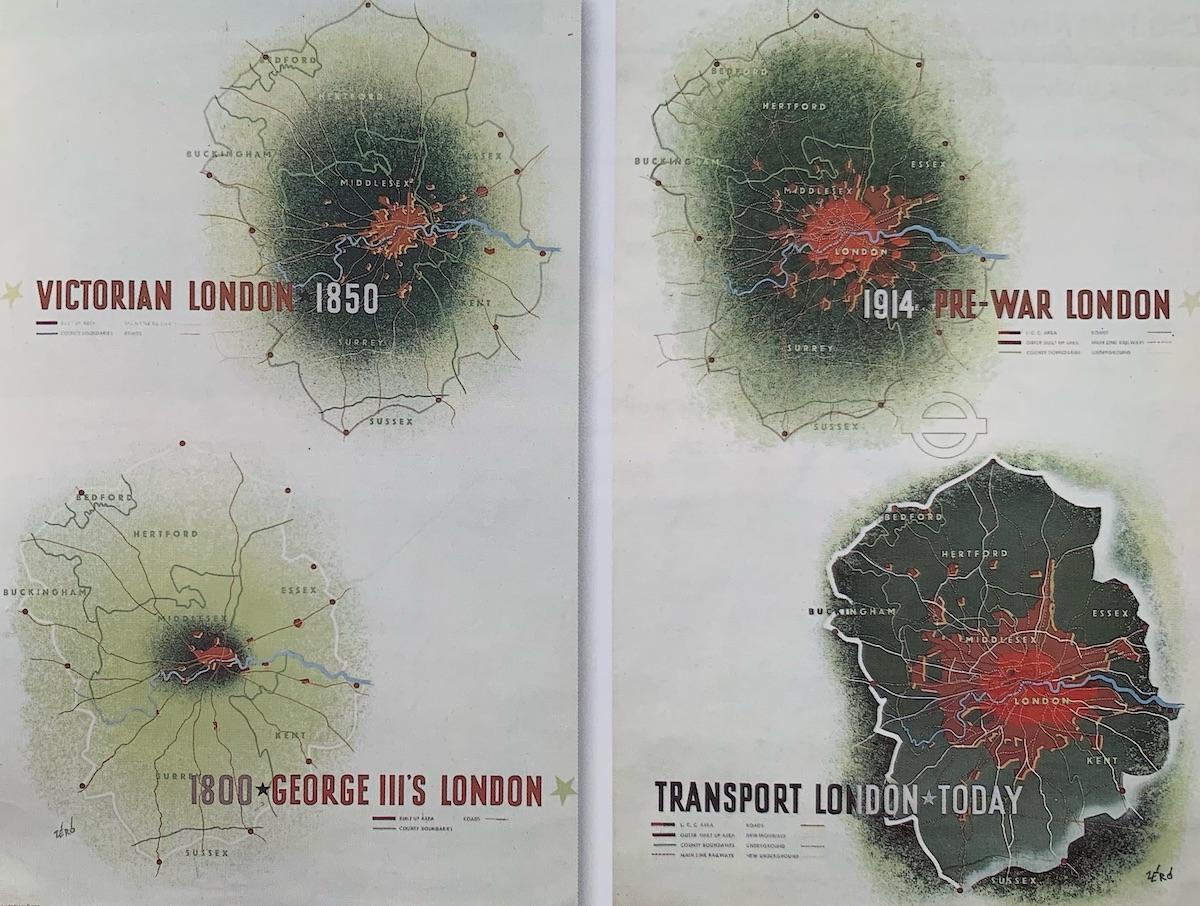

Posters showing the growth of London between 1800 and 1936 (London Transport Museum Guide 2002)

In Tudor times, the River Thames had become the main artery for journeys around the city. Watermen would row small boats (called “wherries”) and they acted as ferrymen, either on fixed crossings of the river or for hire as water taxis along its length from the City to Westminster and beyond – in the film “A Man for All Seasons” Sir Thomas More was rowed home at night from Hampton Court to Chelsea (then only a small village), after an audience with Cardinal Wolsey. The river’s pre-eminence as the City’s highway would be contested during the 18th century by wheeled transport, albeit gradually as the narrow uneven streets made vehicular movement difficult. Four wheeled coaches known as Hackneys (derived from the French “Hacquenee” – a sturdy horse hired out for a journey) became a common sight on London’s streets during the reigns of the King Georges (I to IV: 1714-1830), but they too would be superseded by the horse drawn Omnibus (Latin “for all”), first seen in Paris and then emulated by the coach builder, George Shillibeer in 1829; his route would be from rural Paddington to the Bank via Islington along the New Road at a single fare of one Shilling, which was far beyond the pocket of most workers, but its convenience over other modes of conveyance assured its success.

Reconstruction of the first London Omnibus (London Museum Guide)

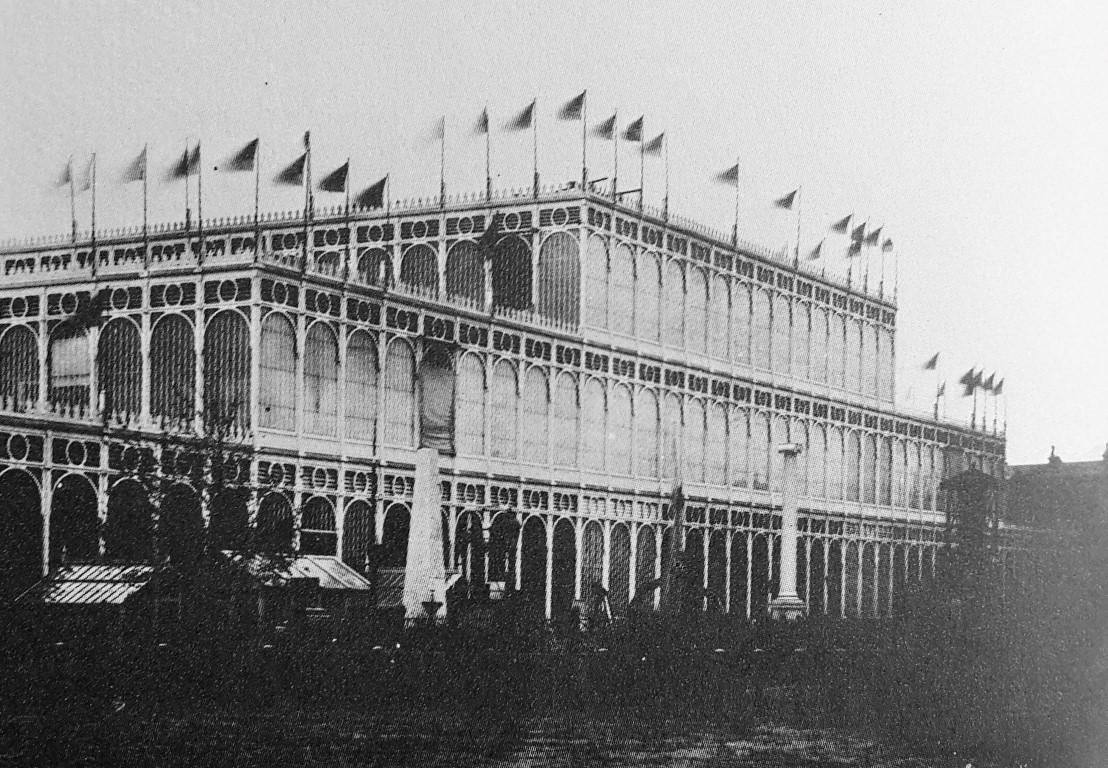

The “Great Exhibition” of 1851 saw its opening on the 1st May in Hyde Park within a huge glass and iron structure, christened “The Crystal Palace” and over the next six months it would have six million visitors to view the latest inventions on display, Bus transportation “boomed” for a while but a “bust” would follow and the many bus operators were faced with bankruptcy or take-over. Two Parisians saw an opportunity in the predicament of the London bus operators and so they registered (in Paris), at the end of 1855, the “Compagnie Generale des Omnibus de Londres” and within a year they had scooped up 600 of the 810 buses running in London and had become the largest single bus company in the world – the “London General Omnibus Company” (LGOC); the General in plain English.

External View of the Crystal Palace (Victorian Engineering)

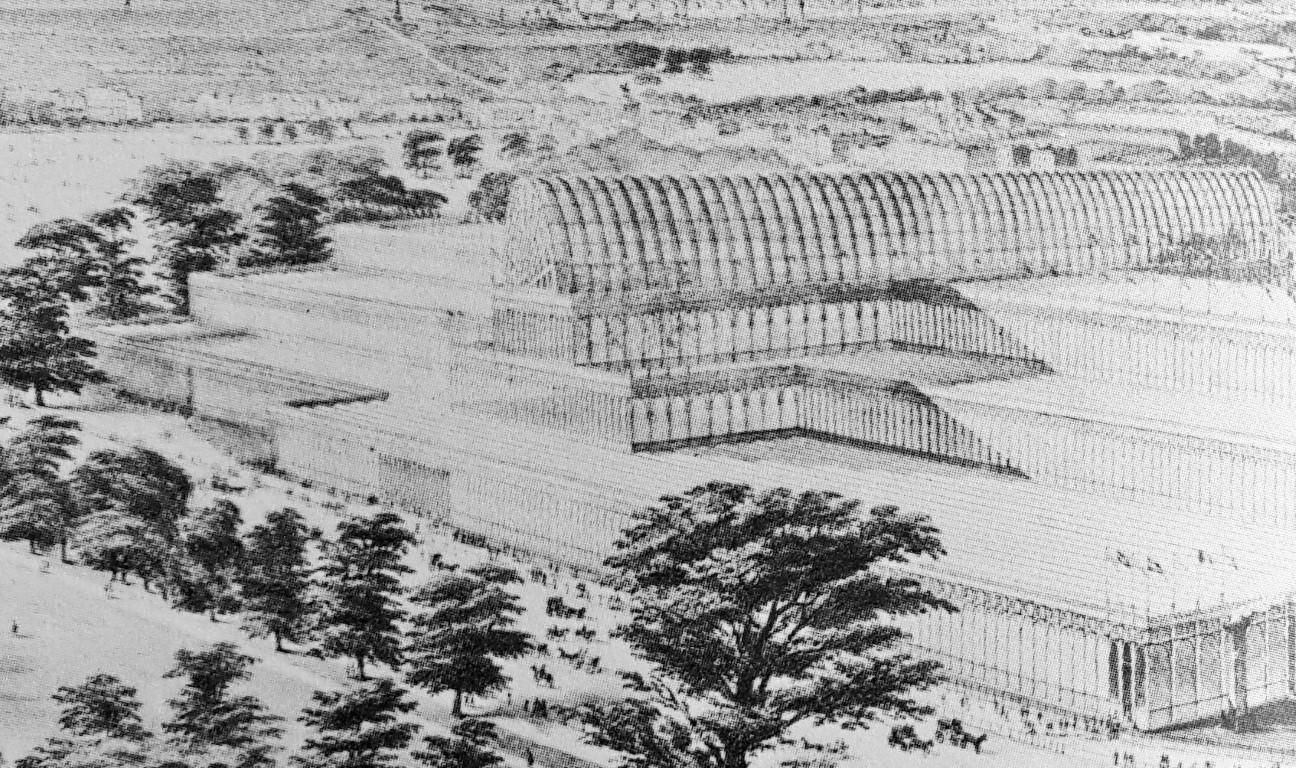

Part of the Crystal Palace from above (Victorian Engineering)

The General would be the main player and innovator in bus matters right up until the formation of the London Passenger Transport Board and its profitability saw it taken over, in 1912, by the “UndergrounD” group (a.k.a. the Combine) led by a British American, Albert Henry Stanley (later to become Lord Ashfield), which ran the underground railway system, except for the Metropolitan Railway (the MET). Horse drawn buses would be gradually phased out in the first decade of the 20th century as motorised buses became more reliable with the X Type (16 inside & 18 on top), of 1909, becoming the first double decker made specifically for London and thus was the precursor for the many types that would follow. Colin H. Curtis in his book “Buses of London” gives a chronological account of all London bus types between the year of 1909 and 1978 – from the X Type to the MCW M Type “Metrobus”.

1870s Knifeboard Omnibus dwarfed by a Metrobus, 1979 (London Museum Guide)

There had been calls for an integrated transport system for London as early as 1863, when a House of Lords committee espoused the idea of a single transport authority for the capital but the actual period for it to come into being would take another 60 years and it would take the form of the London Passenger Transport Board, better known by the contraction “London Transport” (L.T.). The London Passenger Transport Bill was the brainchild of two men, one a capitalist and the other a socialist, the former was Lord Ashfield and the latter was Herbert Morrison the Minster of Transport (in the Labour Government of 1929-1931). Their politics may have been diametrically opposed, but they agreed on one thing, the co-ordination of all of London’s public transport that included buses, trams, trolleybuses (trackless trams) and the underground railways. Morrison presented the Bill to Parliament in 1931 but it was not enacted until the 13th of April 1933, by which time Morrison had lost his seat in the House of Commons and was no longer a Minister. The LPTB was born and it would operate as a quasi-public enterprise, until full nationalisation was enacted in 1948, on the establishment of the London Transport Executive (LTE).

Lord Ashfield would become the Chairman of the new organisation and he began the task of making the combine more integrated and efficient and in his own words “to take such steps as it considers necessary for avoiding wasteful competitive services and for extending and improving London’s passenger transport facilities so as to meet the growing needs of its vast population”. The LPTB would encompass an operating area 2 000 square miles, within a 25 mile radius of Charing Cross. The General, as the largest of the private bus companies to be incorporated set the standard for the way forward; red and cream (around the windows) was its livery and this was adopted for the central area bus services, whereas in the countryside around London dark green (Lincoln green) was preferred as it was considered less intrusive to the surroundings. All was as it should be and Londoners, both in the conurbation and in the “back garden” (the fringes) were looking forward to better transport links, however there were ominous (not omnibus) forebodings of German belligerence that would culminate in World War Two only 21 years after the First had ended.

The Second World War would erupt in 1939 and for the next six years it would put Britain on a war footing and any improvements to London’s transport infrastructure was put on hold. In fact rather than upgrading the system the opposite occurred, thanks to the “Luftwaffe’s” bombing during the Blitz (1940-1941) and the V1 (doodlebug) and V2 rocket attacks (1944-1945). In his book entitled “London Transport Carried On” Charles Graves gives a vivid account of how the workers of L.T. rose to the challenge of keeping London moving.

War damage at Balham 1940 (London and its Buses)

I have a personal attachment to London Transport as my twin brother and I were born in 1948 into a world of bomb sites, austerity and ration books, and my earliest memories are of going on a day trip on a red bus to Brighton (L.T. Private Hire). My parents had met “On the Buses” in 1946 at Cricklewood (W) bus garage where my father was a bus driver and my mother was a conductress (clippie). He had been a Royal Marine and had the Burma Star and she had been a clippie throughout the War. My brother and I were brought up in the Neasden railway village (built by the “MET” before 1933), under the chimneys of the power station (now long gone) that supplied power to energise the L.T. electric trains.

Neasden Power Station (London Transport in the 1950s)

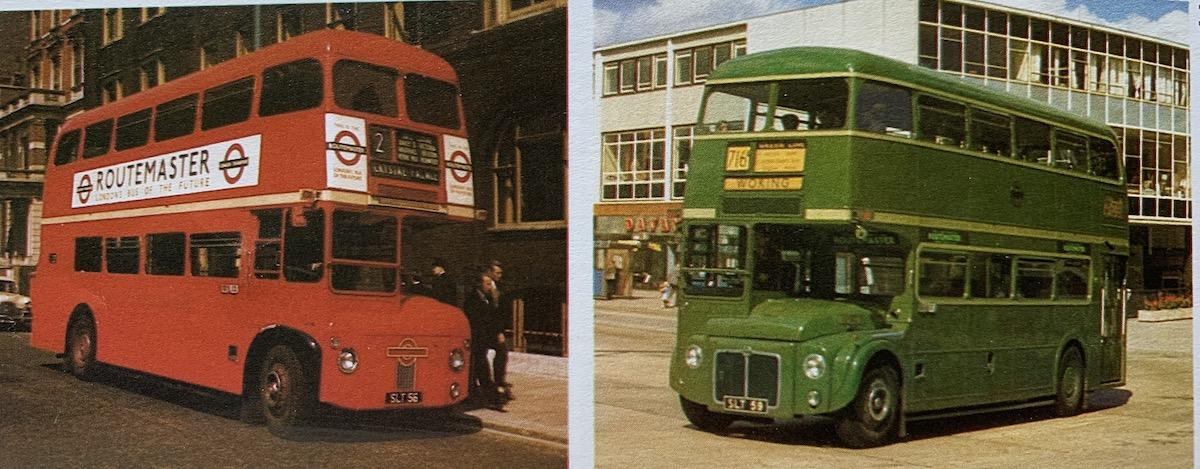

My parents worked together on the Route 2 which ran from Golders Green Station (in the north) to Crystal Palace in the south and my father drove various types of bus, namely the pre-war STL, the pre-war RT (Regent Three) and the post-war RT (which became the standard bus of the 1950’s & 60’s and the replacement for the tram, with nearly 7000 built). It was my father’s good fortune that the new bus for London – the Routemaster (RM) was to be tested on the “2’s” in 1956 and my Dad was one of the drivers of RM1 (AEC engined), one of the four prototypes along with RM2 (painted green for country service), RML3 (Leyland engined) and CRL4 (Green-Line coach); all were extensively tested from 1956 to 1959 to prepare the way for the production series starting with RM5 which entered service in September of 1959 on Route 8 - Willesden Garage to Old Ford. With the introduction of the Routemaster in numbers it would be the end of the road for the venerable trolleybus (emission free) and most were scrapped but for 125 post-war BUT Q1’s which were sold out of service to a Spanish consortium of trolleybus operators at £500 each.

Red RM1 and Green Line CRL4 (The London Transport Golden Jubilee Book)

RM1 (via Wikipedia)

The Routemaster was a leap forward in bus design, as it was aluminium bodied and had sub frames instead of a chassis and its construction owed a lot to aircraft manufacturing techniques learned during the War. Suffice to say here it was a winner and nearly 3000 were built. It outlived the bus that was supposed to replace it, the Daimler Fleetline (DMS) and it was in regular service for 49 years (1956-2005) on London’s streets, some bus!

The last heritage bus Route 15H between Trafalgar Square and Tower Hill which used Routemasters has only recently been discontinued (April 2021) on the grounds of a fall in passenger numbers and the lack of step free access to the platform at the rear. Transport for London (TfL) said that the classic front engined double deckers have been permanently withdrawn. The 10 strong fleet were the last of a line of open backed (hop on, hop off) buses, whose lineage can be traced back 112 years (1909) to the X Type. May the final 10 RMs find new owners amongst the ever growing bus preservation movement.

They say that “Nostalgia ain’t what it used to be” but should you be so inclined take a trip to Brooklands, Weybridge, Surrey where you will find the London Bus Museum and you will be transported back in time when buses were red except when they were green.

Main image: Red RT 811 overtaking green RT 4547 at Uxbridge in 1957 (The Heyday of the RT)

Bibliography

- “Buses of London” by Colin H. Curtis, a London Transport publication, 1979.

- “London Transport Carried On – An Account of London at War 1939-1945” by Charles Graves, published by the LPTB, 55 Broadway Westminster, 1947.

- “London Transport Museum” the original guide to the L.T. Museum, Covent Garden by Peter Stephens, John Freeborn & Oliver Green, published by London Transport, 1980

- “The London Transport Golden Jubilee Book 1933- 1983” by Oliver Green & John Reed, first published by the Daily Telegraph, 1983

- “The London Bus Museum” website www.londonbusmuseum.com

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.