Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

I'm very good at integral and differential calculus;

I know the scientific names of beings animalculous:

In short, in matters vegetable, animal, and mineral,

I am the very model of a modern Major-General.

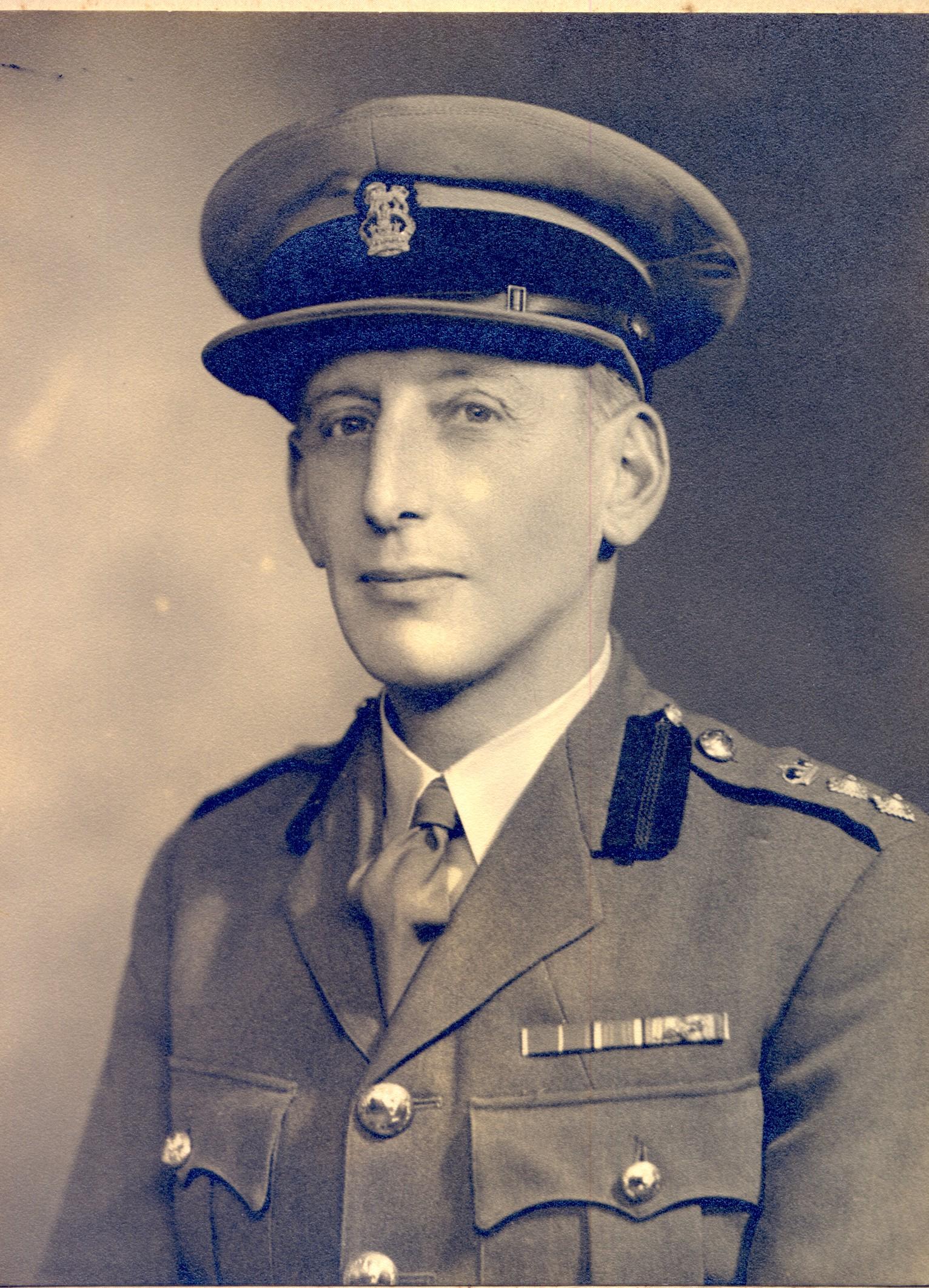

Gilbert and Sullivan’s famous patter song from “The Pirates of Penzance” needs no introduction even though the above extract is actually its second verse. In the context of the tale I’m about to tell it captures the essence of the man concerned rather nicely. He was Sir Basil Schonland CBE OMG FRS, scientist, soldier and a remarkable servant of two prime ministers plus a redoubtable field marshal.

Sir Basil Schonland

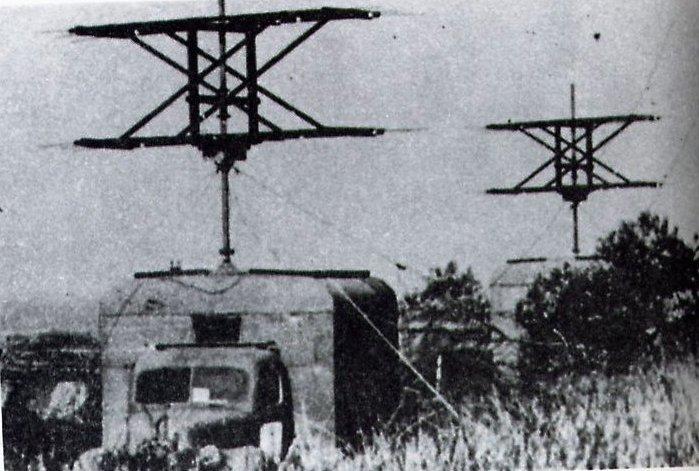

In March 1944, Brigadier Schonland was appointed Scientific Adviser (SA) to Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery’s 21 Army Group, just two months before the invasion of Europe - known as Operation Overlord. It was rather late in the day considering the task that lay ahead of him. Schonland had come to this position after serving, since 1941, in Britain’s Air Defence Research Establishment (ADRDE) and then as the superintendent of the Army Operational Research (AORG). Prior to that, as a Lieutenant Colonel, he was CO of the Special Signals Services (SSS) of the SA Corps of Signals, where he had led South Africa’s remarkable effort to develop a radar system ultimately intended for the defence of the country’s 3000 km coastline. That seemingly daunting task was accomplished in just three months.

Special Signals Services Mobile Radar, Cape Town

At the time of Schonland’s appointment to serve Montgomery, the British and Canadian armies, along with the huge American forces, were massing along the south coast of England. Schonland’s role, as he put it was to ensure that the recommendations of the Operational Research Sections (ORS), embedded within the Army, were acted upon. Whereas scientists are expected to know about technical things, such as radar, gunnery and communications, they have a more fundamental part to play in the analysis of military operations and it was this that dominated the activities of ORS2, as it was known. However, the Scientific Adviser himself must always be ready to solve what Schonland called “conundrums”. These were the occasional questions asked by the General Staff when confronted with an issue usually outside their purview as military men but considered to be well within that of the SA. Examples included the accuracy of radar-controlled guns, the likelihood of a headquarters being targeted as a result of its signals being monitored by radio direction-finders and a matter of some concern to those soon to embark on a massed landing on the beaches of Normandy: could the enemy “electrify the sea” by running cables from a nearby power station out into the bay?

These matters, and many more, kept Schonland and his small team of officers – both British and Canadian - extremely busy. But then, almost out of the blue, came another most unexpected assignment.

On 24 August 1944 Paris was liberated. The French 2nd Armoured Division entered the city accompanied by the Americans. It was a day of huge significance, particularly for the leader of the Free French Forces, General Charles de Gaulle. It was his moment of triumph. By contrast, the Supreme Allied Commander, General Dwight Eisenhower, saw the semi-chaotic scenes of massed crowds that accompanied the driving-out of the last remaining Nazis from the French capital as more of a distraction from his major task of forcing his way into Germany and decapitating the remnants of Hitler’s Third Reich. But diplomacy required him to divert, as briefly as possible, from that course in order to appropriately honour and support the French.

General de Gaulle and his entourage stroll down the Champs Élysées (Wikipedia)

The U.S. 28th Infantry Division on the Champs Élysées in the "Victory Day" parade on 29 August 1944 (Wikipedia)

For his part, Britain’s most senior officer in the field, Field Marshal Montgomery, would have none of it. The battles that lay ahead far outweighed any pomp and pageantry, he said, especially if the intention was simply to assuage the ambitions of de Gaulle. But others around Monty, especially his Chief of Staff, Major General ‘Freddie’ de Guingand, were much more sensitive to the clamour for France to be seen to be triumphant and the British Army must be seen to be supporting them – at least nominally. A suitably high-ranking British officer must, therefore, be in attendance when the massed French and American forces marched down the Champs Elysees. But could such a senior man be spared? He could if he was not a fighting soldier in the front line. And that man was Basil Schonland.

Basil Schonland in 1915

‘On instruction from the C-in-C he assumed the acting rank of Major General. The C-in-C desired this as it was presumed that it would suit the French better’. So wrote Felix Schonland, Basil’s younger brother, in letters to the librarian at Rhodes University in Grahamstown. He then elaborated on why this brief promotion of his much-revered brother was not listed formally in his military record which began in 1914 when Private B.F.J. Schonland joined the First Eastern Rifles in Grahamstown.

Though he had been seconded to the British Army on his appointment to the AORG in 1943, Basil Schonland remained attached to the South African Corps of Signals as a special adviser to its Director of Signals, Colonel (later Brigadier) F. Collins. On being informed that he was to go to Paris wearing the crossed swords and batons on his epaulettes, Schonland therefore felt it would be inappropriate were his rank to be gazetted as Major General as it could lead to difficulties in his dealings with Collins to whom he was still answerable in a rather roundabout way. His promotion to General rank, in order to assuage the sensitivities of the French, was therefore a ‘promotion in the field’ to carry out a specific function. On his return to 21 Army Group he reverted to his rank of Brigadier. And, being the modest man he was, Basil Schonland told no one (other than his doting brother) of his brief foray as a Major General.

Such oddities are very much in keeping with the ways of war and were by no means unusual. When circumstances demanded it, the commanding officer had it within his power to make such promotions in the field. And no one would have challenged Monty when he made such decisions! Schonland was indeed a Major General, if only briefly.

About the author: Dr Brian Austin is a retired academic from the University of Liverpool. Born and educated in South Africa, where he studied Electrical Engineering at Wits, he spent a decade in industry, mainly at the Chamber of Mines Research Organisation where he led the team that developed the world’s first “direct-through-rock” underground radio system. He then joined his alma mater as an academic before emigrating with his family to England where he joined the Department of Electrical Engineering and Electronics at the University of Liverpool. Now retired he has long had an interest in military history and especially the part played by radio and radar in all conflicts. In 2001 his biography of Sir Basil Schonland, called “Schonland Scientist and Soldier” was published. He served as an officer in the South African Corps of Signals (CF) for many years. He was recently awarded the Master of Signals Commendation of the Royal Corps of Signals.

References

- B.F.J. Schonland, ‘On Being Scientific Adviser to a Commander-in-Chief (21 Army Group 1944-1945). Canadian Military History Journal vol.15, Issue 3, 2006.

- F.W.J. Schonland, letters (MS11046) written to the librarian, Cory Library, Rhodes University: 11 March 1963 and 28 April 1976.

- B.A.Austin, Schonland Scientist and Soldier, IOP Publishing and Wits University Press (2001).

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.