Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Early photographs lacked the realism of the painted portrait in that the production of a photograph in colour at the time of its invention was not feasible.

A great deal of scepticism as well as excitement came about during the development of photography in the 1840s. While some hailed it as a revolutionary step in the quest for artistic realism, others were concerned about what the new medium would mean for traditional artistic practices.

The very nature of photography raised philosophical questions about art itself. If a “machine” could produce an image portraying realism, what implications did it have for the artists? The question of whether photography could be considered "art" lingered for decades, as the view was that it lacked the manual skill and conceptual depth that many traditional artists believed were integral to true artistic expression.

The early photographic processes, such as the Daguerreotype (introduced in 1839), Calotype (introduced in 1841) and the Ambrotypes (introduced early 1850s), were monochromatic images in shades of black, white, and grey. Adding colour made them more visually appealing and bridged the gap between photography and traditional portraiture which were often produced in colour.

Portrait painters, who had once enjoyed a monopoly on representing human likenesses, found themselves in direct competition with daguerreotypists. The speed, accuracy, and affordability of photographs appealed to a wide audience, making portraiture accessible to the middle-class who could not afford expensive paintings.

Following the invention of the photograph, monied sitters were not satisfied with their likenesses being produced in black and white. They needed to have their likeness produced in colour. In an attempt to create more realistic images and meet customer expectations, photographers and artists started hand-colouring these monochrome photographs, resulting in skilled colourists blurring the lines between photography and painting.

As early as the mid-1840s, the first recorded South African hand-colourists, Carel Sparmann, advertised that he coloured daguerreotypes. He would however not have coloured carte de visite photographs.

Several other recognised artists and portrait painters in the Cape also tried their hand at photography at some stage, many of whom did not survive the industry for long.

Deviating slightly – about the Daguerreotype and Ambrotype format photographs - these portraits did not appeal to all (whether coloured or not) in that Graaff Reinet-based Harriet Rabone, stated in a letter to a friend in 1863: “I will try and get a good picture – not a little object shut up in a little case, which portraits I thoroughly dislike and feel strongly inclined to throw out of the window when my English relations send them” (Rabone, 1966).

In the early 1860s, photographic colourists soon began colouring the first paper-based photographs, the sepia-coloured carte de visite, primarily to meet the growing demand for more lifelike and personalised images.

Photographers also saw hand-colouring as a way to differentiate their service offerings to add value. This service allowed studios to charge higher prices for the "enhanced" carte de visite. Due to the additional cost of finishing off a carte de visite in colour, only a handful of South African photographers offered this as an additional option for visitors to their studios.

Carte de visite photographs were relatively inexpensive compared to painted portraits, making them accessible to a broader audience. Hand-colouring of the carte de visite photograph was still a more affordable way for people to enhance their photos and make them look more luxurious.

Often displayed in Victorian photograph albums or passed on as a gift, adding colour to carte de visite photographs gave them a more lifelike, vibrant and decorative appearance resulting in them standing out as unique and aesthetically pleasing keepsakes. Back then these photographs were cherished personal possessions and became family heirlooms.

This article only focuses on the first commercial paper-based photographic format, the carte de visite photograph that was occasionally hand-coloured by some South African photographers or a professionally appointed hand-colourist (or artist) between the early 1860s and mid-1870s.

Only colour applied by hand to the actual carte de visite is included in this article. Artistic copying, reproduction, or enlargement of original carte de visite photographic images is not discussed. Some artwork was also reproduced by artists in carte de visite size format – these are not photographic images and are also excluded from this article.

A beautiful hand-coloured Carte de Visite (CdV) format photograph of an unknown sitter by Cape Town-based photographer SB Barnard (circa 1868)

A detailed hand-coloured Carte de Visite (CdV) format photograph of an unknown sitter by Cape Town-based photographer Lawrence Brothers (circa 1872). Some light colour was applied to the sitter’s face. Not only was the carpet painted with absolute precision, but also the chair and background. The red paint on the curtains shows paint cracks on the photograph, confirming that hand-painted photographs deteriorate if not stored optimally.

Hand-coloured Carte de Visite (CdV) format photograph of unknown sitter by the Cape Town-based photographer SB Barnard (circa 1870). Barnard, along with Arthur Green, may have been the first South African photographer to have hand-coloured their customers Carte de Visite format photographs on their request. Here the artist gently applied colour to the lady's cheeks, lips, hair band, dress and jewellery.

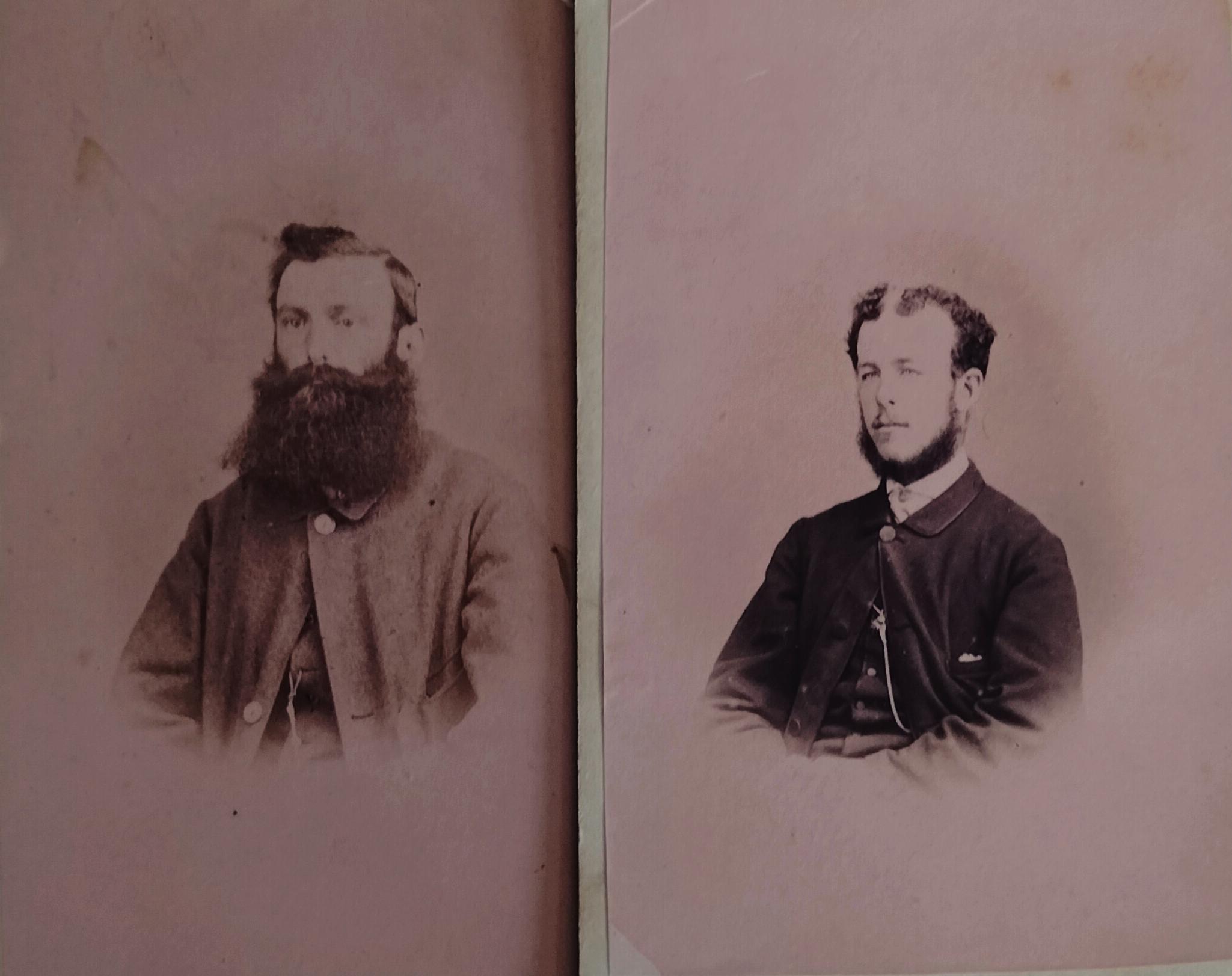

Two hand-coloured Carte de Visite showing the difference in quality and colouring technique applied on these images. The photograph on the left (photographer and sitter unknown) is an example of hand-colouring applied by a professional colourist with outstanding skills whilst the image on the right is an example of poor-quality hand-colouring skills probably applied by an amateur artist. The photographer of this image is Shoyer from Cape Town (he later took over the SB Barnard studio). The sitter is George Wellen or Weller, the grandson of the artist Rob Lee. It is not known whether Rob Lee himself coloured the image after receiving it from the studio or whether the photographer had it coloured at the request of the sitter.

Two CdVs in full colour by the Graaff Reinet-based photographer William Roe (circa 1875). It has been suggested that Roe advertised that he hand-coloured photographs himself. The sitter on the left is unknown whilst the sitter on the right is the singer Miss Rhymer.

Full-colour CdV by Cape Town-based James E Bruton of an unknown sitter, probably an actor (circa 1875)

Carte de Visite in South Africa

The carte de visite, or visiting card, commonly abbreviated to CdV, is a small photographic format, which was patented in Paris by photographer André Adolphe Eugène Disdéri in 1854.

It was the overwhelming popularity of the carte de visite that led to the word Cartomania and the eventual institutionalisation of photography. Cartomania refers to a Victorian-era craze in the production and collection of mass-produced photographs of celebrities, royalty, friends and family.

In South Africa, the Cape Town-based photographer, Frederick York, became the first recorded carte de visite camera owner which was presented to him by Prince Alfred in February 1861. York however does not seem to have used the camera, instead, his successor Arthur Green, was the first photographer in South Africa to have produced CdV format photographs. Green also happens to be one of the photographers who offered hand-coloured CdVs as a service.

From 1862 until the mid-1870s, for a period of roughly 13 to 15 years, Cartomania in South Africa followed the European trend in that photographers quickly adapted to this relatively cheaper new format, resulting in every citizen that could afford to have their likeness captured visiting the photographic studio in town or ensuring that they obtained photographs from family and friends alike.

The carte de visite (64mm x 100mm) was usually an albumen print from a collodion negative on thin paper glued onto a thicker paper card. The front of the card often contained the photographer’s name and the town he (or she – yet it initially remained a very male-dominated career) was active in, whilst the reverse of the image may have included the logo of the studio for advertising purposes.

Two lightly hand-coloured CdVs of unknown sitters by the Cape Town-based photographer SB Barnard (circa 1875)

Two effective hand-coloured CdVs of unknown sitters or photographers. The image on the left has “Property of MH Lister” inscribed on the back.

In this delicate hand-coloured CdV by the Cape Town-based photographer Joseph Kirkman, the unknown sitter’s face, hand and chain around her neck have been emphasised by adding colour (circa 1872).

Two CdVs produced by Cape Town-based photographer SB Barnard (circa 1871). The image on the right is not of the best quality in that the child’s face has become distorted. Also, note the paint smudge on the right of the same image. The girl on the left has been recorded as being Lilla Spence.

Two CdVs (circa 1870) with sloppy attempts to apply some colour to the images. The image on the right is by Port Elizabeth-based photographer JE Bruton. Note the baby is sitting on the lap of an adult. In the image on the left, both the sitter in his fraternal clothing and the photographer are unknown.

Hand-Coloured Photographs

A variety of means have been used since the days of the earliest photographic format, namely the daguerreotype, to manually add colour to the surface of the black-and-white photographs, including watercolour and other paints and dyes. Brushes, cotton swabs and airbrushes were used for application.

At the time of capturing the image, colour details were often meticulously recorded by the photographer, such as eye, eyebrow and eyelash colour as well as dress fabric details. This may also have included a smudge of the female sitter’s lipstick for example. Locks of hair were also taken from sitters of both genders.

Obtaining a hand-coloured photograph was a significantly more costly option for the sitter explaining why so few are seen some 150 years later.

Hand-colouring should be distinguished from tinting, toning, retouching, and the crystoleum.

Tinted photographs are made with dyed printing papers produced by commercial manufacturers – no hand-colourists were therefore involved in the process. Tinted CdVs were not popular in South Africa and are even scarcer than the hand-painted versions. The Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection (HPRC), for example, only contains two tinted CdVs (shown below).

Two examples of tinted CdVs produced by the Cape Town-based photographer Lawrence Brothers (1868). Tinted photographs are not to be confused with hand-coloured photographs. Tinted photographs consist of a single overall colour of the photographic paper where a commercial manufacturer added dyes to the paper.

Hand-coloured photographs are accepted as a branch of the arts. The artists, or hand-colourists, were also referred to as photographic miniature painters. The skill of hand-colouring is also referred to as hand-painting or overpainting.

Popular images, more so in Europe and elsewhere, were painted on a production-line basis (images of Royalty for example). It is unlikely that there would ever have been “production-line colourists” in South Africa.

Some identified South African-based photographic hand-colourists

Earlier colourists remain largely mystifying in that little is known about them due to them working in the background without much acknowledgement. Colourists were mostly highly skilled but went unacknowledged in South Africa in that they did not sign their finished work which makes the identification of colourists near impossible.

Some carte de visite painted abroad contained the name of the colourist on the back, yet no hand-coloured carte de visite produced in South Africa, containing the name of the colourist has been identified to date.

Only a few South African-based artists became photographic hand-colourists – although the uptake in hand-coloured images was initially low, the eventual uptake still did not provide enough work on offer in South Africa. It remained a costly affair in that it required third-party intervention (where the photographer did not do the colouring themselves). Some artists were therefore lucky enough to be afforded the opportunity to generate an additional income by painting photographs for photographic studios (where the photographer did not perform the function themselves) resulting in photographers and artists mingling and mixing their different art forms.

Hand-colourists did not solely focus on photographic hand-colouring. They were mainly artists (painting, sketching) but also fulfilled several diverse functions such as teaching, cartoonists, newspaper employees or curating an art collection.

On occasion, the final result on a hand-coloured CdV would also have been disappointing for the sitter in that the artist or photographer did not optimally master the colouring of the photograph - as can be seen in the examples of poorly hand-coloured photographs included in this article.

The colour in coloured photographs often faded, resulting in a new method of colouring photographs being announced by both the South African Photographic Saloon of Cape Town and James Bruton (then Port Elizabeth-based) in August 1864, referred to as the Sennotype. This method was previously introduced in Australia by its inventor, Charles Wilson. The coloured portrait was subjected to a chemical process that not only fixed the colours, but “imparted to it the appearance of having been executed on ivory.”

Without the outstanding work by Bull & Denfield (1970), our knowledge and appreciation of the work done by hand-colourists in South Africa would have been even further diluted.

The names presented below do not purport to be a complete list of all hand-colourists active in South Africa. There were certainly more hand-colourists of early photographs which remain unrecorded.

Photographers with an artistic bent, such as Groom, Eckley and Hamilton did their own colouring (Bull & Denfield, 1970) whereas others like Bruton, Green and Barnard had enough work on hand to employ full-time colourists. Occasionally this type of work was also outsourced to an external professional artist.

The list below only records the names of hand-colourists who were artists first and foremost. Long-standing photographers with an artistic flair in terms of painting have been excluded. Should they be included the list will grow at least 10-fold.

The list below, therefore, excludes the names of long-standing well-established photographers who are suspected to have hand-coloured their own work at some stage, such as Arthus Green, Wiliam Roe, Samuel Baylis Barnard, James Bruton or the Lawrence Brothers.

Although hardly noticeable, both ladies had slight colour applied to their cheeks. The lady on the right also had a tinge of colour added to her lips with some green applied to the plants/peacock feather in front of her. The CdV on the right is by the Grahamstown-based photographer Augustus Brittain. Although the photographer of the CdV on the left is unknown, the image is inscribed "Rykie van der Byl" on the back.

In this CdV by the Cape-Town-based photographer JH Kaupper, not only has colour been added to the sitter’s face, but her eyebrows and eyelashes have also been emphasised. She is holding a photographic case, probably an Ambrotype.

Simple, yet effective. The only colour applied to this image by an unknown photographer is to the cheeks and lips of the unknown female sitter.

An interesting CdV by the Cape Town-based photographer Johann Heinrich Kaupper where only the flower pinned to the unknown young lady’s dress has been coloured. Note the photo number applied by Kaupper bottom right of the image, namely 13462 (circa 1872).

Two hand-coloured CdVs by the Cape Town-based photographer SB Barnard (circa 1868). The sitters in both images are unknown. The photograph on the left shows a paint smudge on the cheek of the female sitter.

Examples of two neatly hand-coloured British CdVs. Both photographs are by Cambridge-based photographers Farren Bros (circa 1870). Just considering these two examples it is generally accepted that the South African colourists, although some may have originated from abroad, did not match the quality of hand-colouring achieved by their foreign counterparts.

An inferior quality hand-coloured CdV by Cape Town-based SB Barnard (circa 1872). The bride is C. Wicht who forwarded the image to a friend, Mrs van der Byl, suggesting that she was satisfied with the quality of the image. To add to the ghostly appearance, the artist added two dots to amplify the bride’s pupils. SB Barnard stands out as the photographer who produced more hand-coloured photographs than any other early Cape Town-based photographers. It is therefore surprising to find such poor-quality images being released by his studio. The original, unpainted image would no doubt have been a better version.

Recorded photographic hand-colourists of carte de visite were:

- Chapman Frederick (1836 – 1886) - Also recorded as being a photographer

Born in Liverpool, Chapman emigrated to South Africa in 1862. He gave lessons in drawing and oil painting. He had a close association with F. Heldzinger whose studio was based in Bree Street, Cape Town. It has been suggested that this association inspired him to become a photographic colourist.

Chapman introduced his own special method of colouring photographic portraits in oil, a process which was received with acclaim. The S.A. Advertiser and Mail recorded in September 1869 that “They were beautifully done” and “good indeed as first-class oil paintings, and then we have the advantage of not having to pay above 1/10th of what a first-class portrait in oil costs”.

Chapman opened his studio in December 1869 in Loop Street, Cape Town.

- Dashwood Francis Lewin (1821 – 1898) – Also recorded as being a photographer

Born in London, Dashwood emigrated to South Africa in 1858.

In February 1860, he joined the Arthur Green Photographic Studio where he was employed as a full-time photographic colourist.

In August 1861, he turned to photography and opened his studio Bridge House on Bathurst Street, Grahamstown, specialising in coloured photographs – a venture that only lasted a few months.

He passed away in Queenstown in 1898.

- Essex Charles (1823 – 1869) – Also recorded as being a photographer

Essex was born in London in 1823 and arrived in Cape Town in either 1839 or 1840 where he worked as a clerk.

Charles was however described as unsuitable to have performed the work as a clerk since he was epileptic following which he returned to England, the date of which is unknown. He has been described as industrious and persevering, despite his continuous illness.

Back in England Charles worked as an apprentice to a steel engraver but also had his employment there terminated due to his ailment, following which Charles studied art and worked for renowned artists in England from whom he learned much of his artistic techniques. He worked in crayon, water-colours, and plaster. He produced many medallions and busts from life in plaster.

Back in South Africa, one of the medallions was of Dr A. Melvin in 1856. This artwork was described as the first artistic work of its kind that has been attempted in the Eastern Province and that it has been most successfully executed.

On the invitation of his older brother, Alfred, Charles returned to South Africa in 1854. Essex ended up in Graaff Reinet where the entire Essex family from England eventually settled (Older brother, two sisters and his father). His older brother Alfred started the Graaff-Reinet Herald in 1852.

In 1857 Essex first advertised his activity in photography which he relinquished 6 months later.

In the catalogue of the Third Fine Arts Exhibition, held at the Council Chambers in Cape Town in 1858, six of Essex’s works were listed.

In 1859, Essex was listed as a portrait painter, residing at 50 Plein Street and 16 Wale Street in 1860 (same address as the British photographer Thomas Brown Adlard resided at).

Towards the end of 1861, Essex was colouring photographs for William Roe in Graaff-Reinet.

Essex passed away in Graaff-Reinet in 1869. Ironically, no records exist of him at the South African National Archives.

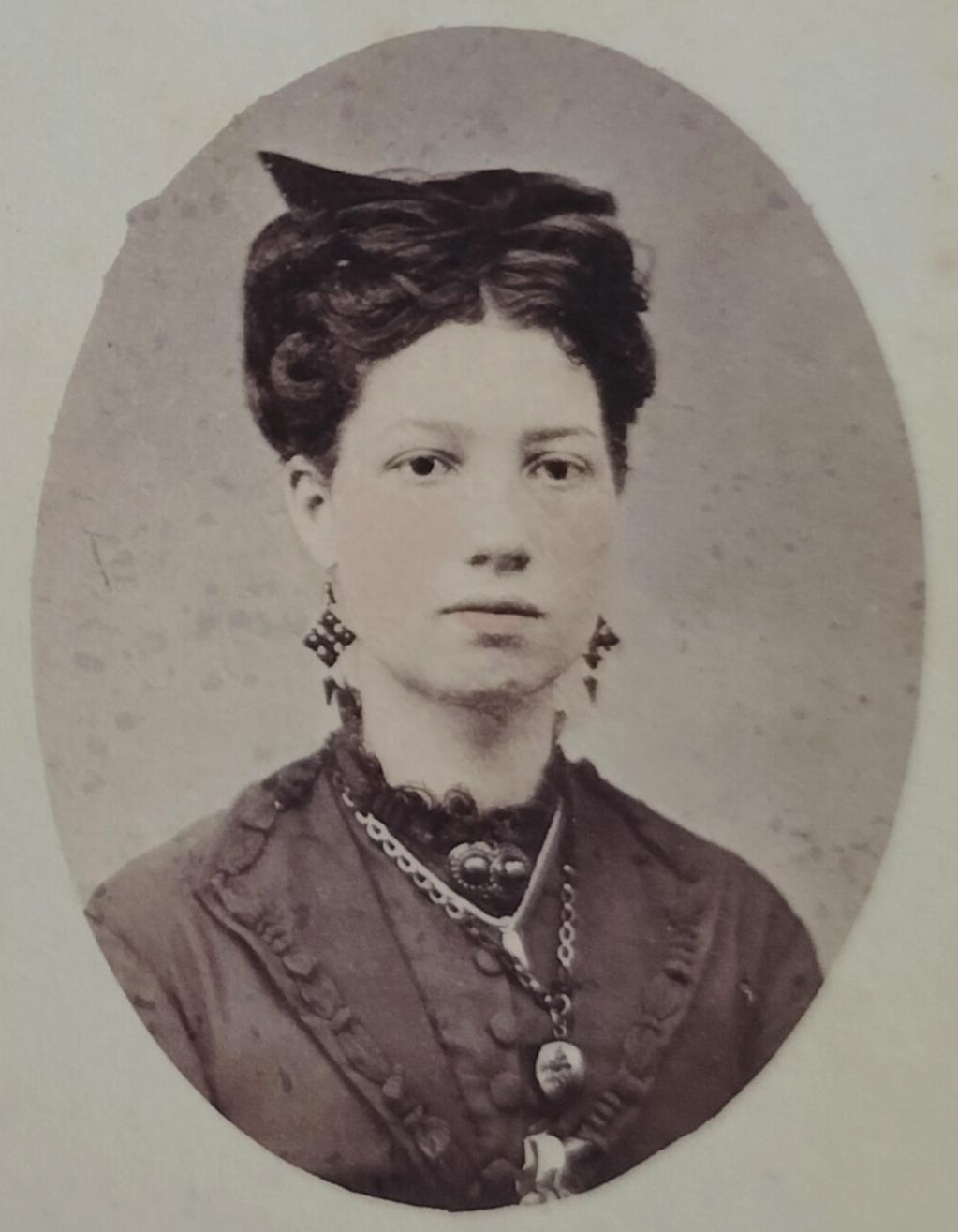

Self-portrait by Charles Essex (Images provided by Cory Library). Charles died at the young age of 46 in Graaff-Reinet in 1869. It has been suggested that he suffered of a number of medical ailments.

- JP Holst (date of birth and death unknown)

A decorative artist and portrait painter, he first appeared at 11 Boom Street, Cape Town. He executed landscapes and portraits in oil either from life or from photographs or lithographs. He also coloured photographs. Examples of his work also appeared at the Fine Arts Exhibition of 1866.

- Robert Brown Fowler Lowe (1842 – 1886)

Described as the most important of all the photographic colourists in the Cape at the time, he appears to have first advertised in 1864. He specialised in enlargements by hand from photographs finished in oil, Indian ink and crayon. He introduced the “Fowlerite” process of colouring whereby photographs were painted by a new and improved process with a durable protective surface.

His marriage certificate confirms that he was an artist. He married Eleonor Amy Lowe in May 1864 but divorced her in 1868 whereafter he married Elizabeth Jane Tothill in March 1869.

He opened the “Academy of Art” towards the end of 1874.

Although Bull & Denfield (1970) suggested that Lowe was South Africa’s best photographic hand-colourist in South Africa, none of his work has been seen by me to make an informed judgment.

Lowe was also a mentor to a younger hand-colourist (see Schröder below).

- Oberg Hendrik Theodorus (1822 – 1875) – also recorded as being a photographer

Sources differ in terms of place and year of death. One source cites Utrecht as the place of birth (1829) whilst the second states Doorn (1822) as the place and year of birth.

Oberg is recorded as having been a Cape Town-based artist and clerk between the period 1863 – 1880.

Oberg advertised that he coloured carte de visite at one shilling each and in addition to his portrait painting and photography, he made enlargements by hand from photographs in various media.

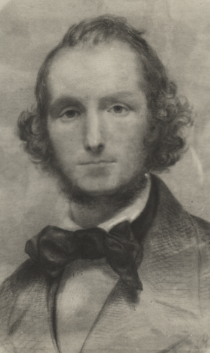

Hendrik Theodorus Oberg (Reproduced from Africana Notes and News)

- William Howard Schröder (1852 – 1892) – also recorded as being a photographer

Schröder is recorded as South Africa's first full-time cartoonist in addition to being a prominent artist and a pioneer of self-publishing in South Africa. He published a weekly periodical called The Knobkerrie in the Cape Colony between 1884 and 1886. During his career, he did cartoons for The Zingari, The Lantern, Transvaal Truth, The Cape Argus, Het Volksblad and many others.

Schröder (also spelled Schroeder) was born in South Africa on 2 April 1852. He had three brothers and six sisters (four of his sisters died at a very young age).

At the age of 14, Schröder was compelled by his family's straitened circumstances to leave school and work for a photo colourist (Lowe), resulting in him becoming proficient in this art form. Later he was employed by the photographer, Samuel Bayliss Barnard. He remained in Barnard’s employ for some twelve years during which period he attended evening classes in art, first studying under Thomas Lindsay of the Roeland Street School of Art, and later under Lindsay's successor, W. McGill (Wikipedia).

Langham-Carter (1973) provides us with the following additional snippets as it relates to William:

- William’s grandfather, John, was a shoemaker and was married to a Cape Malay lady by the name of Dorje. William was named after his uncle and godfather;

- William’s father, also John, was a coachman and butcher who grew up illiterate;

- Due to his father facing bankruptcy, a family friend ensured that the ownership of all household furniture, shop fittings and tools of the butcher trade was transferred to William, who was only thirteen at the time;

- Wiliam married Anne Jane Turner, who also worked for the photographer SB Barnard, on 27 January 1876. Barnard, the couple’s employer, signed the marriage register as a witness;

- William, sang in a choir along with two of his brothers;

- William attended a private school of high standing for a while, but due to the family not being able to afford his schooling, he had to begin earning his own living at the early age of fourteen;

- Another artist, RB Lowe, who supplemented his income by colouring photographs took William, who showed artistic talent whilst at school, under his wing;

- From 1866 William worked for Samuel Baylis Barnard whose photographic studio in Adderley Street he had often been to fetch work for colouring by Lowe. Barnard too was an artist. He continued William’s training and proved a sponsor and good friend;

- William participated in his first exhibition in December 1871 where, amongst others, he showed a water-colour of a Bushman. Barnard also exhibited three pieces of William’s artwork which he in all probability purchased from William;

- William has also been recorded as being a photographer living at the Anglican college of Zonnebloem in 1873 and 1874, a skill he probably developed whilst working for Barnard;

- William was appointed the custodian of the Cape Town-based art gallery towards the end of 1877. He also resided on the premises for a while;

- William is recorded as an artist and teacher of drawing in 1875 and between 1878 and 1886 he held the post of art head at St. Saviour’s Grammar School at Claremont;

- William also secured his brother a post at SB Barnard. What he did at the Barnard studio is not clear, but it is recorded that between the period June 1884 to December 1886 he edited and drew for the magazine Knobkerrie.

William did most of his portraits in oils or Indian ink. His artwork, which appeared as supplements to newspapers, was copied from photographs.

Despite his mounting reputation, William found it difficult to earn enough to support his growing family and he decided to try his fortunes at the newly founded gold town of Johannesburg in 1889, where he worked for two periodicals but not before shipping off his wife and five children to England.

Available work in Johannesburg proved to be disappointing resulting in William moving to Pretoria where he worked for The Press.

Following pneumonia, at 40 years of age, William passed away in Pretoria at the President Hotel in August 1892, leaving his family destitute in England.

Leo Weinthal (editor of The Press at the time) and others organised a public appeal for funds with which to publish a selection of William’s cartoons. Through this process, it was hoped to raise £1 700 for the family.

So big was the response, that The Cape and Natal Governors Loch and Mitchell as well as Presidents Kruger and Reitz consented to be patrons.

Amongst the initial subscribers were the likes of Cecil Rhodes and Alfred Beit as well as William’s old master SB Barnard.

Weinthal also had a headstone made for William’s grave. It has been hypothesised that Anton van Wouw may have designed and carved the headstone.

Two years after his death, a commemorative book titled 'The Schroder Art Memento: A Volume of Pictorial Satire Depicting our Politics and Men for the Last Thirty Years, in Black and White, by South Africa's Only Artist' was released.

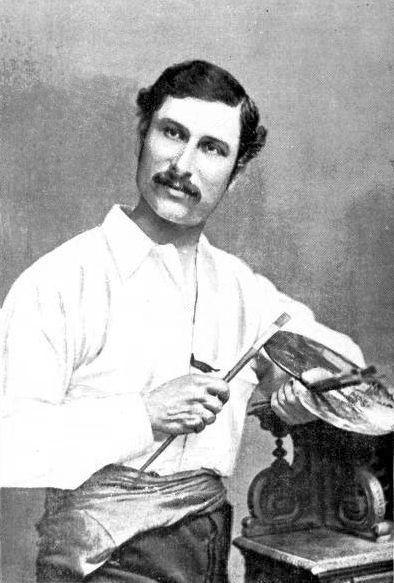

William Howard Schröder (Wikipedia)

- William Tasker Smith (date of birth and death unknown)

Smith was not a full-time professional artist but did advertise that he coloured photographs, amongst others. He exhibited several hand-coloured photographs at the Fine Arts Exhibition of 1858, where he was also awarded the prize for the best portrait.

He must have left South Africa around the late 1850s or early 1860s in that between 1865 and 1867, he shows up as the appointed British Consul in Savannah, Georgia, America.

- CJM Smith (date of birth unknown– 1875)

Smith described himself as the first transparency painter in the Cape Colony during 1855. He painted photographic backgrounds and coloured photographs. He also occasionally advertised the sale of cameras. Most of the illuminated transparencies on the occasion of Prince Alfred’s visit in 1860 were executed by Smith.

Five of his paintings were exhibited in the Fine Art Exhibition of 1866.

A brief snippet on Smith’s wife indicates that she was an amateur actress and a member of Ray and Cooper's initial company, but later disappeared from the scene, having been replaced by other actresses, since she was apparently rather mediocre and not popular with the Cape Town public.

- Morgant William (date of birth and death unknown) – also recorded as being a photographer

An artist from Paris, Morgant arrived in Cape Town in September 1849. He turned to photography in 1853 becoming the first Cape-based photographer to use both the calotype and daguerreotype processes. It is also recorded that he became the first photographer to introduce painted backgrounds. He is recorded as a collodion photographer in 1861 specialising in the colouring of photographs. His studio closed down around June 1865 when he left the Cape Colony.

Closing

Ultimately, the rivalry between artists and photographers did not lead to the demise of painting, but rather to the evolution of both art forms. As photography matured, it became an integral part of the art world, not as a rival to painting, but as a medium with its own unique possibilities and aesthetic value. Through this creative tension and mutual influence, both art and photography flourished, shaping the visual culture of the modern world.

Less than 3% of South African CdVs were hand-coloured (calculation based on the number of hand-coloured CdVs in the Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection). This small percentage confirms the overall rarity of South African hand-coloured CdVs.

The “hype” in having photographs coloured after 1875 seems to have declined in that the percentage of hand-coloured South African cabinet cards that became popular from the mid-1870s onwards (a larger format to the CdV), is even smaller.

Our appreciation for seeing imagery in colour, has resulted in software packages being developed to assist with the colouring of antique images.

One such example is the unique work done by Tinus le Roux, where he purely focuses on imagery of the Anglo-Boer War era. He has published one book on the theme, with the second book due for release in early 2025.

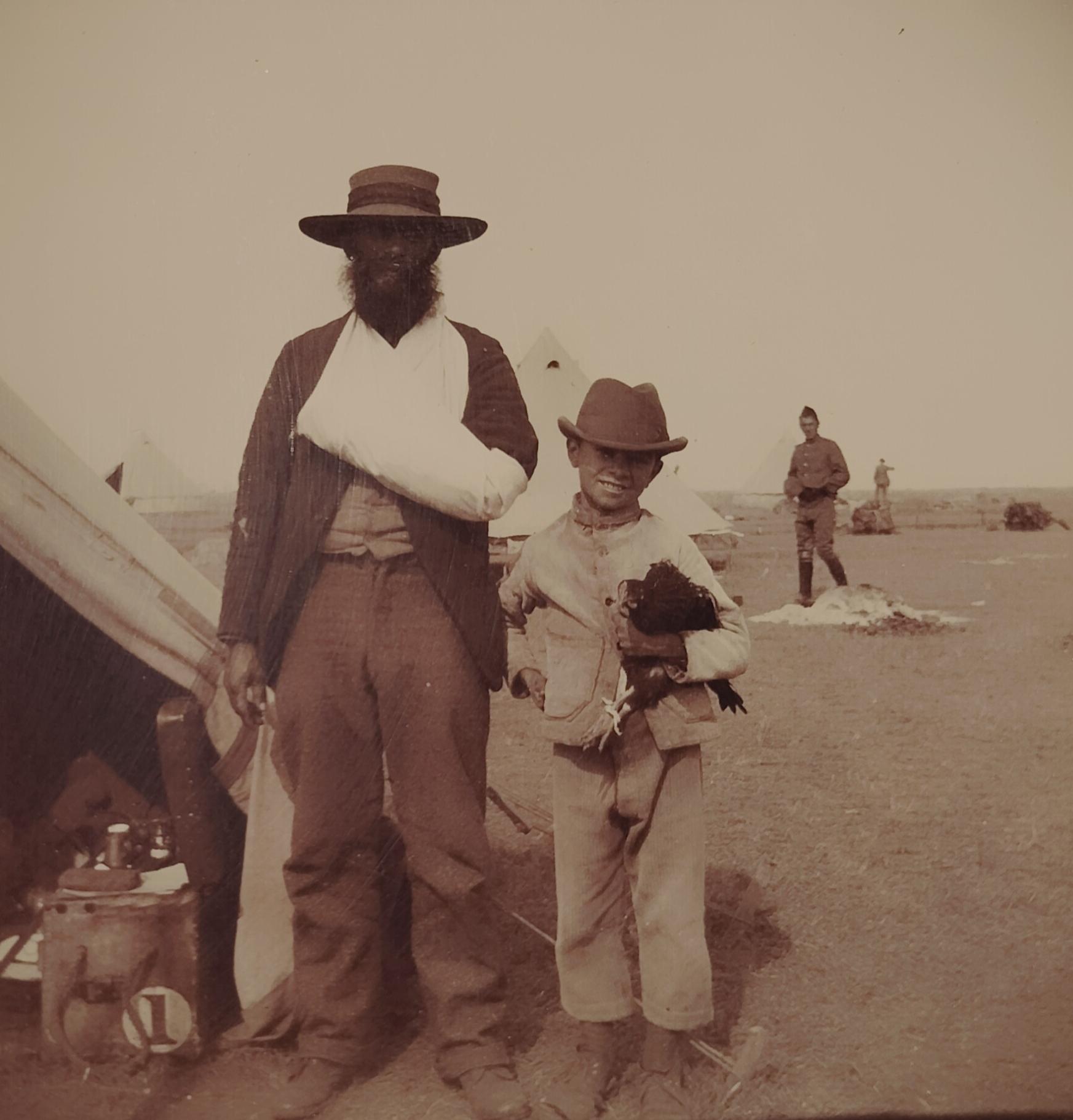

Original Anglo-Boer War photograph of father and son being held in an unknown concentration camp. Note the young boy holding his pet chicken.

The same image as above, coloured by Tinus le Roux

Special acknowledgement

- Prof. Kathy Munro for sourcing the articles on Oberg and Schröder from the Africana Notes and News from her library

- Louisa Verwey for providing an electronic copy of the Charles Essex sketch held by Cory Library – Rhodes University

- Faiek Ariefdien for sourcing the Charles Essex article from the Africana Notes and News – National Library South Africa (Cape Town)

- Dr. Ansie Malherbe for providing two sources as it relates to Charles Essex

Main image: Another two full-colour CdVs by Cape Town-based James E Bruton (circa 1874). Both sitters are of unknown Cape Malays. It is unlikely that the sitters would have requested for the images to be coloured. Bruton in all probability had the photographs captured and coloured with the intention of commercial on-sell

About the author: Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources

- Baldwin, G. (1991). Looking at Photographs – A Guide to Technical Terms. J Paul Getty Museum. California

- Bull, M. & Denfield, J. (1970). Secure the shadow – The story of Cape photography from its beginnings to the end of 1870. Terence McNally. Cape Town

- Cory Library – Rhodes University – Charles Essex sketch (PIC/M3)

- De Jong, C.J. (1991). Hendrik Theodorus Oberg – Artist (Africana Notes and News – March 1991 Vol 29 No 5)

- Esat (Extracted 20 November 2024). Mrs Smith (esat.sun.ac.za)

- Frecker, P. (2024). Cartomania – Photography & Celebrity in the Nineteenth Century. September publishing. England

- Hannavy, J. (2005). Case Histories – The Presentation of the Victorian Photographic Portrait 1840 – 1875. Antique Collectors Club. Suffolk

- Langham-Carter, R.R. (1973). Background to Schröder. Africana Notes and News – March 1973 Vol 20 No 6

- Levine, R. (extracted 25 November 2024). Twelve original early South African political cartoons by WH Schroeder (antiquarianauctions.com)

- Malherbe, A. (1998). ‘n Kultuurhistoriese ontleding van gebou en bewoner: Gevallestudies van Residensie en Avondrust, Graaff-Reinet (Thesis – University Stellenbosch)

- Rabone, L. (1948). Charles Essex (Africana Notes and News – 1948 No 3)

- Rabone, A. (1966). The records of a pioneer family – Essex, Rabone & Co. Struik. Cape Town

- Sparham, A. (2024). 100 Photographs from the Collection of the National Trust. Gomer Press. Wales

- Wikipedia (extracted April 2024). William Howard Schroder. (Wikipedia.com)

- Wikipedia (extracted November 2024). Hand-colouring of photographs (Wikipedia.com)

- Wikipedia (extracted 9 November 2024). Carte-de-Visite (Wikipedia.com)

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.