Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

On a trip to Carnarvon in the Northern Cape, South Africa, in 2009 I had some spare time to walk around the town and admire the clean, bright ambiance of the place. I discovered that the town’s hot streets had been planted over the years with a variety of exotic trees, mostly Eucalyptus (Eucalyptus grandis). It was evident that the smooth pale bark of the Eucalyptus trees had become the irresistible surface for informal messages and designs. Some of the incisions reminded me of some of the more abstract scrapings of rock art and even of the Blombos Cave artefacts and engraved ochre dating to 70 000 years ago. This probably all goes to show that human beings, confronted with a flat surface, will find a way to draw on it!

The Uniting Reformed Church in Carnarvon was built in 1858. Note the many street trees.

Blombos Cave Artefact (via Wikipedia)

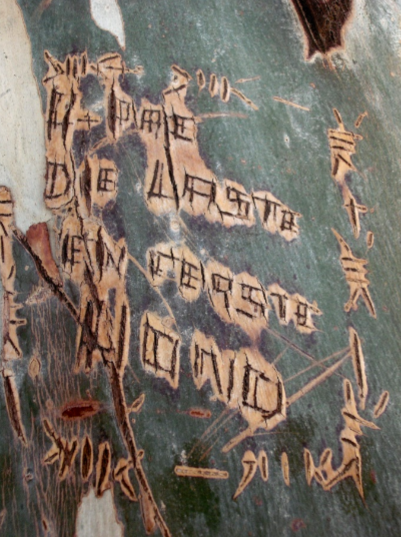

One of the engravings on the Carnarvon Eucalpytus pavement trees.

Apart from the diversity of marks on the trees, what fascinated me was the intensity of tree decoration. All the Eucalyptus that I observed were heavily decorated with lines, images, words and bottle caps designs – or even embedded with the actual bottle caps. Many of the trees served as ‘drinking trees’ where people gathered in the shade to drink and pressed their bottle caps into the trees, creating lively patterns, perhaps commemorating happy times. Trees in urban public places in South Africa have often endured some kind of random defacement, but as a whole, the Carnarvon ‘tree archive’ (perhaps a total of 50 Eucalpytus trees) showed a comprehensive set of intentional marks, words, symbols and decoration. In some parts of the town young lovers had cut their initials into the smooth white bark, while still other persons had cut and scraped designs and words onto the trees. I have never seen anything quite like this! Without further research, the age of the trees and their engravings is unknown – although they are unlikely to date back to the town’s origin in 1853.

Bottle top engravings

Heritage in Carnarvon

Carnarvon is a lovely old town with a very strong Cape influence in the architecture, language and culture. Carnarvon itself is very old, established in 1853 on a trade route between Cape Town and Botswana that was followed by early explorers and traders. It was originally established as a mission station of the Rhenish Missionary Society, and at some point, freed slaves from Cape Town moved to Carnarvon and build a new life for themselves. The Rhenish Mission at Carnarvon catered largely for an ethnic group known as the Basters, descended from White European men and Black African women, usually of Khoisan origin, in the Cape Colony. The Basters are closely related to Afrikaners, Cape Coloured and Griqua peoples of South Africa, with whom they share a language and culture. Interestingly, many of the messages were in English, even though Afrikaans in the most widely spoken language in Carnarvon. The Baster settlement with its historic links to freed Cape slaves outside the main town is being restored. Many of the buildings in and around Carnarvon are listed as heritage buildings.

What is not mentioned on the tourism and heritage websites are the Eucalyptus street trees of Carnarvon and their striking decorations. This collection of tree engravings forms an ephemeral archive of sorts – if only it could be linked to events and persons. As the outside bark of all trees is shed over the years as the trees expands, and with Eucalyptus grandis, strips of bark peel away all the time, so the Carnarvon tree archive is not permanent. The messages and designs will gradually age and be lost.

Text messages carved on the surface of Carnarvon's Eucalyptus trees will age, peel away and be lost over time.

Archives and allowing forgotten voices to be heard

A common theme in contemporary archival research is that archives and archival research enable researchers to recreate the past and allow forgotten voices to speak and counteract what is seen as a ‘routine silencing of marginalised voices’ by history. Much contemporary research on archival material seeks to re-engage with the material in a fresh way and allow those neglected voices to speak – often in the context of slavery or colonialism. Archaeology and anthropological research also seeks to do this by uncovering civilisations, settlements, artefacts so that people and their lives, now long gone, can be revealed. Even after more recent events like wars and atrocities, the authentic voices and lives or ordinary people are quickly lost, or drowned out by the voices of experts, politicians, even by the viewpoints of photographers and journalists. Especially for the poor of the world, artefacts like photographs, diaries, maps and archival objects are not often possessed or kept and transferred to the next generation. This renders the lives of ordinary persons invisible to history, even though they may have witnessed key events.

It would seem that the ‘tree engravings’ at Carnarvon are an archive of sorts, representing a record of ‘moments in time’ when someone stopped at those trees and made their mark. According to archive theory, these markings represent an intention of now forgotten persons to be seen and for their messages to be read, perhaps to achieve some kind of ‘temporary permanence’ in the town. These are the messages to loved ones, messages just to say “I was here”, message to remember loss (‘Laste en eester hond’) or perhaps messages of boredom while waiting for something to happen.

‘Laste and eerste hond' message carved into a Carnarvon street tree. A beloved dog? The barbed wire decoration around the message is a lovely observation on the part of the scribe-artist.

Carnarvon is a remote town, being seven hours drive to Cape Town, and out of the mainstream. Individual human lives could definitely be invisible to mainstream society, and quickly forgotten. The Carnarvon street tree engravings can thus be considered the messages of the invisible in our society, the transient, the mobile, messages of youth, of drinking parties and gatherings at the side of the road (there are dozens of crown bottle caps pressed into the trees) and of people waiting in the shade of trees with friends . It could be safe to say that the people who made these marks, who pressed the bottle caps into the bark were the poor of the town, those who walked everywhere rather than had a car, those who had nowhere nice to meet other than at the side of the road in the shade of these Eucalyptus trees, or those ‘poor boys’ who would have waited for their girls on a summer evening at these trees rather than in the lounge of a local hotel.

‘A secret message to my love’ on a Carnarvon street tree.

Many of the engravings are abstract designs and mark-making. Some may be indicating the female genitalia and are the closest the Carnarvon tree engravings get to ‘smut’. There are no four-letter words or phallic carvings at all, which seems remarkable.

Delicate representations of female genitalia?

Abstract design of lines and circles, meaning unknown.

Some of the engravings are assertive yet incomprehensible.

Imported trees and colonialisation

Carnarvon is situated in the Northern Cape, in an area of South Africa known as the Great Karoo, part of the dry interior with very unique vegetation (aloes, mesembryanthemums, crassulas and many others). There are very few indigenous trees in this semi-arid landscape. However, the towns in the Northern Cape required shade tree plantings in the streets and homesteads, so imported species were used. As the maximum temperature in summer in Carnarvon can be 33° C, shade becomes an important asset of the town.

Eucalyptus species come from Australia where they are well-adapted to a hot, arid environment. For this reason, they do well in South Africa, growing almost everywhere. So, although Carnarvon is a very dry town, with no natural trees, and with a sparse summer rainfall of around 215 mm per annum, Eucalyptus trees do very well. Australian trees were not introduced into southern Africa until the late eighteenth century when the British began to settle parts of southern Africa. The British occupation of the Cape Colony in 1806 encouraged an extensive series of exchanges of plants between southern Africa and Australia. Some of these introductions have proved to be a disaster, as we all know (Port Jackson willow, Hakea on the Cape Flats).

Some of the trees in Carnarvon have been felled, but as Eucalyptus coppices very easily, an entire new tree has grown up next to the old one, now with its set of new tree graffiti. So, the tree engraving is likely to be an on-going form of urban art and expression in Carnarvon. Research and local interviews would be needed to fully clarify the meaning and age of the carvings, exploring the engravings as an archive of sorts.

About the author: Sue Taylor holds a PhD in Plant Biotechnology from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, and has worked in the agricultural sector doing crop biotechnology research. She recently spent five years at the University of Pretoria, South Africa, coordinating an African mountain science network funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC). During this time she organized two mountain research conferences, one in Ethiopia and one in Tanzania. Her current research interest is in creating resilient cities in Africa and the value of trees, parks and public open spaces. She is Research Fellow at the Afromontane Research Unit, University of Free State (South Africa).

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.