Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In 2014 the monthly magazine “Civil Engineering” (published by the South African Institute of Civil Engineers) ran a series of articles entitled “A brief history of transport infrastructure in South Africa up to the end of the 20th century” (comprising ten chapters issued from January/February to November 2014), which gave an interesting account of the history of our roads, railways, harbours and airports. The author of the articles was Dr. Malcolm Mitchell, Senior Fellow of the SAICE, and in “Chapter 1: Setting the Scene”, he encouraged his readers to participate and add additional value to the topic. This is what I hope to do in a series of articles that will appear on the “Heritage Portal” in the coming months. To get the ball rolling I shall give an overview of today’s road infrastructure and then go back in time to when there were no roads only trails.

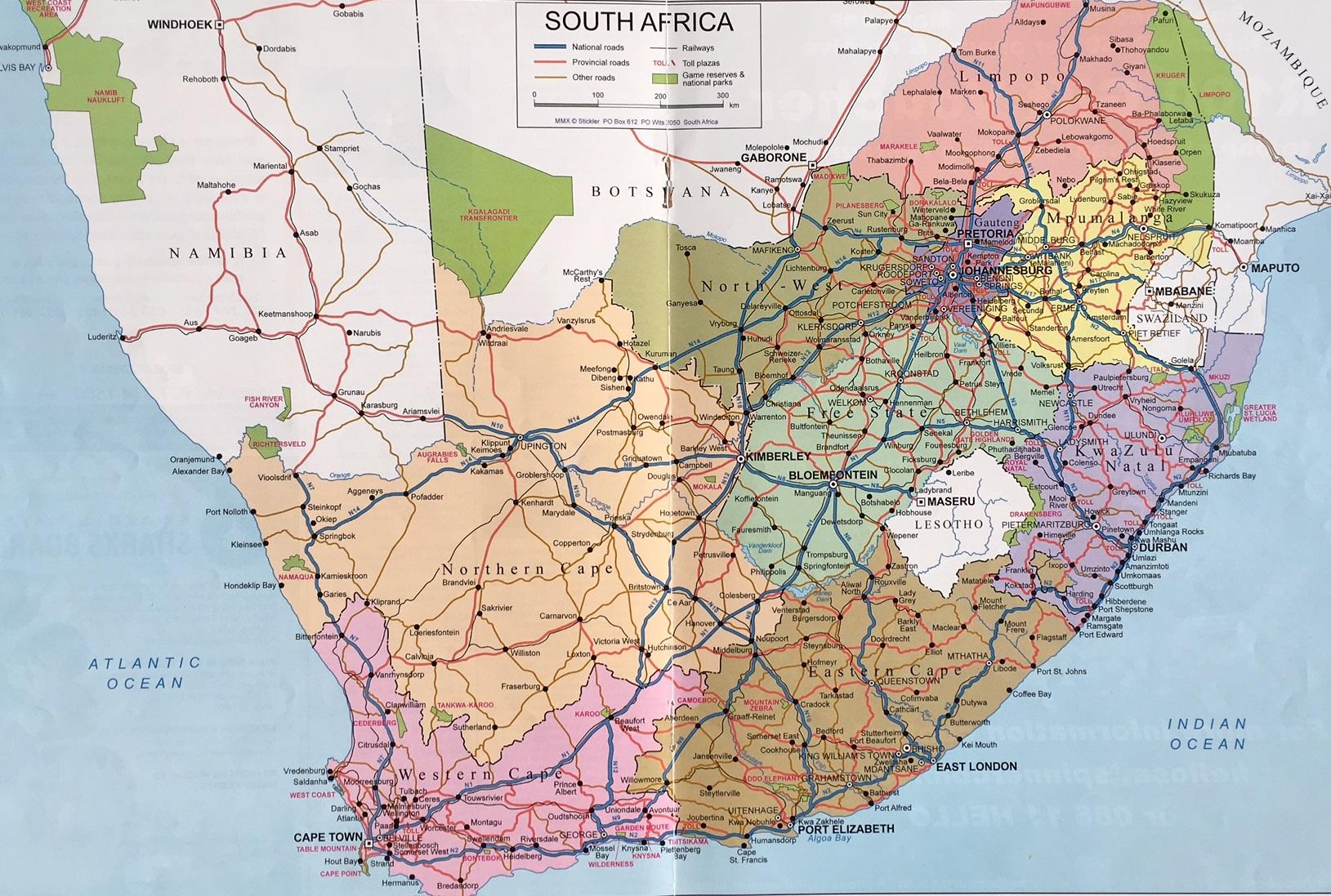

Road Map of South Africa (Durban 2012)

A three week summer holiday trip to the Cape, from Johannesburg, which entailed a round trip of 4000 km, opened my eyes to the splendour of our beautiful land. It would have been an easy option to hop on an aeroplane and arrive in Cape Town two hours later but to do so would have meant missing all that was in between. In the words of the song “Route 66” sung by Perry Como:

Mister, you may, have travelled near and far, but you haven’t seen the country, till you’ve seen the country by car! Mister, may I, recommend a royal route? It starts in Illinois, let me tell you boy! If you ever plan to motor west, travel my way it’s the highway that’s the best! Get your kicks on Route 66! It winds from Chicago to LA, more than 2000 miles all the way! Get your kicks on Route 66!

“Route 66” is a great number and although Jo’burg to Cape Town is only half the distance, at around 900 miles (1450 km) the sentiment of the song is just as valid; the object being not so much to rush the trip, but to enjoy and savour the changing scenery and take two or three days to get there. There are several towns in the vast Karoo that make the weary traveller welcome and depending on what route one takes the favoured “dorps” for an overnight stop would be Philippolis (R717) Colesberg (N1), Graaff-Reinet (N9), Oudthoorn (N12, R62) and Montagu (R62); Bloemfontein (N1) and Kimberley (N12), although destinations in themselves are also worthwhile for an overnight stop.

South Africa’s modern road network has been planned and developed over the last eighty years or so with its main trunk routes – the National Roads (i.e. N1, N2 etc.) being well built and maintained (by SANRAL) having good road surfaces and signage with a maximum speed limit of 120 kph (75 mph). The provincial roads (i.e. R45, R62 etc.) are reasonably good roads and in some cases are the previous routes taken by National roads (e.g. R103 & R717), these roads are not as wide or as well maintained and potholes are sometimes encountered to slow one down. Our major roads are in the main tarred, although gravel is encountered where there are low volumes of traffic notably in the “Platteland” (country districts).

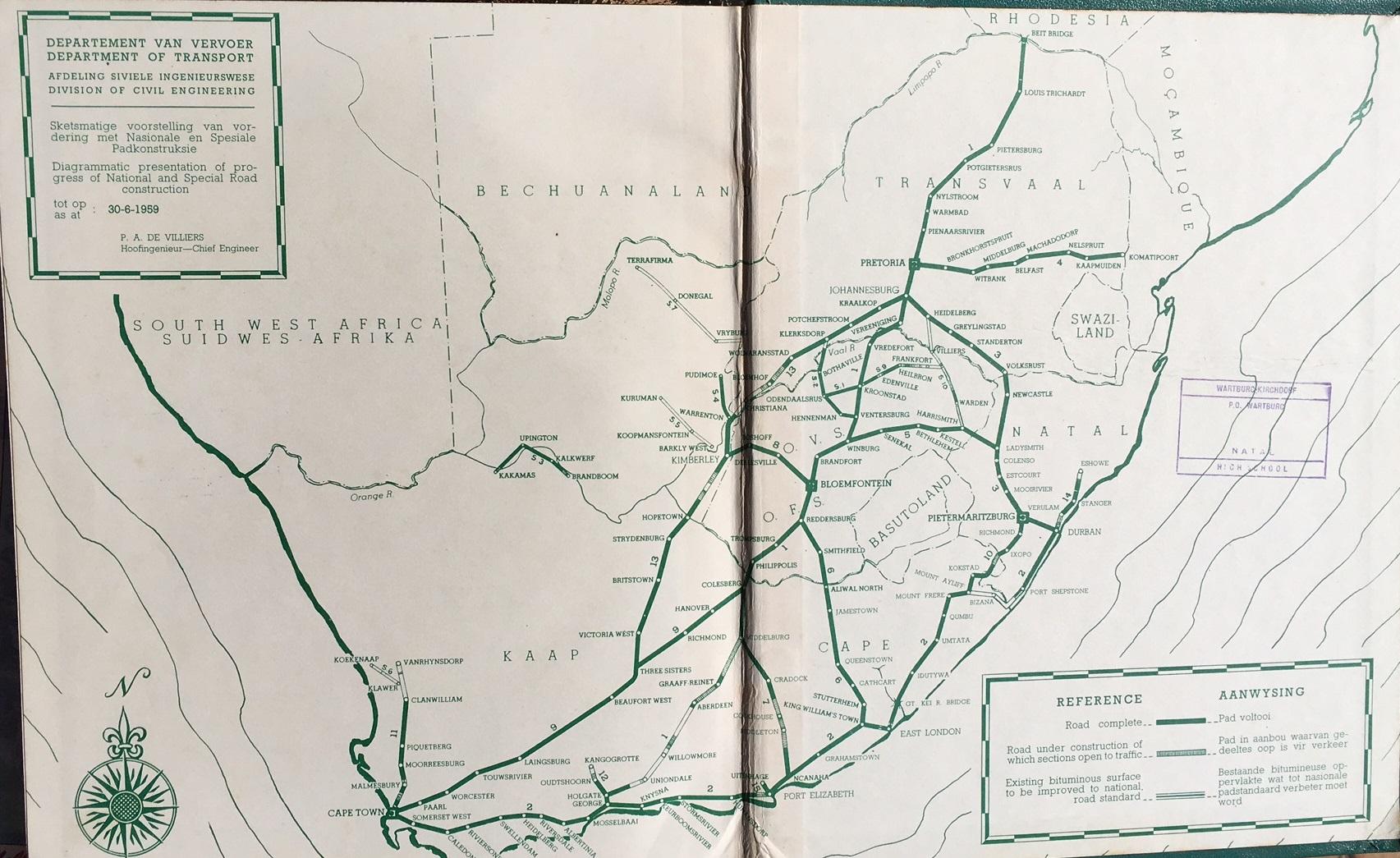

Department of Transport Map from 1959

Should we travel back in time, say by two centuries (to 1817), the road and rail links, that we take for granted and make possible fast and efficient transportation, were not even in the minds of those who lived back then and roads were no more than ruts in the ground made by ox wagons, with very little purposeful road formation except perhaps on the banks of a river at a fording point (drift).

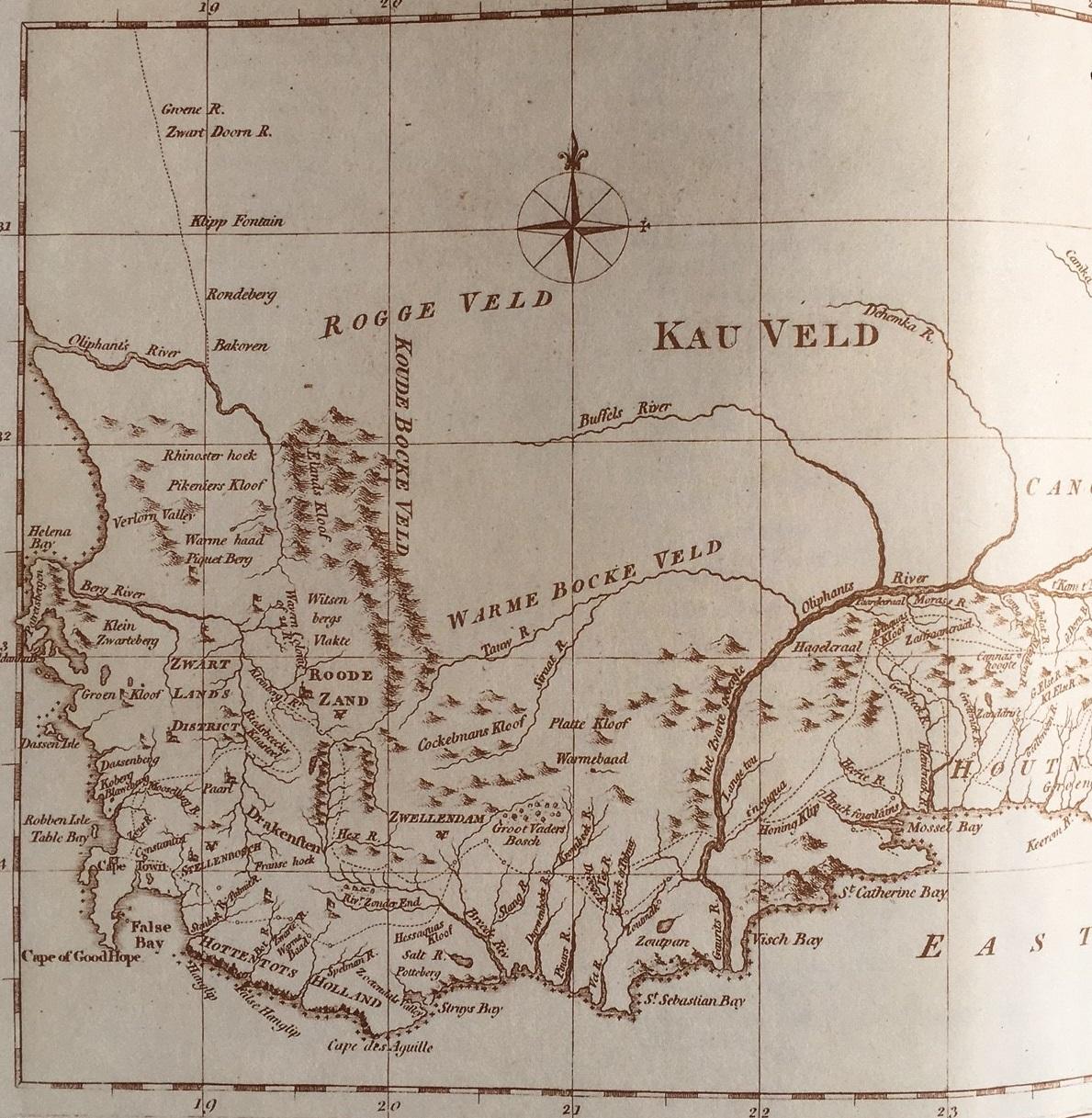

The British at the end of the Napoleonic Wars were handed (at the Congress of Vienna 1815) the former Dutch Colony of the Cape of Good Hope, which they had been “in occupation” since 1806. Britain’s main interest was a strategic one, to keep control of the sea lane between the Atlantic and the Indian Oceans in order to protect its sea route to India. Cape Town was seen as the “Tavern of the Seas”, a port of call to and from India and little was done initially to develop the Cape Colony, but as time went by efforts were made by successive governors to improve communication between the Western Cape and the Eastern Cape, which had been settled by Trekboers and those who had arrived from Britain – the 1820 Settlers. The development of South Africa stemmed from the Cape whence explorers, hunters, traders, missionaries and Trekboers (farmers looking for new pastures) set off in a north-easterly direction, the latter taking part in the exodus from the Cape Colony to be known as the “Great Trek” (1837-1845). To go due north was to go into the Kalahari desert.

South Africa has many parallels with the United States of America, as both began as far flung colonies of European nations. Both Cape Town and New Amsterdam (New York today) were founded by the Dutch within a few years of each other. Both trekked into the wilderness to found new states. Both would throw off the yoke of British rule. However the topography of North America was far kinder to the Americans as compared to the lie of the land of South Africa, as the former had navigable rivers which made the opening up the interior much easier.

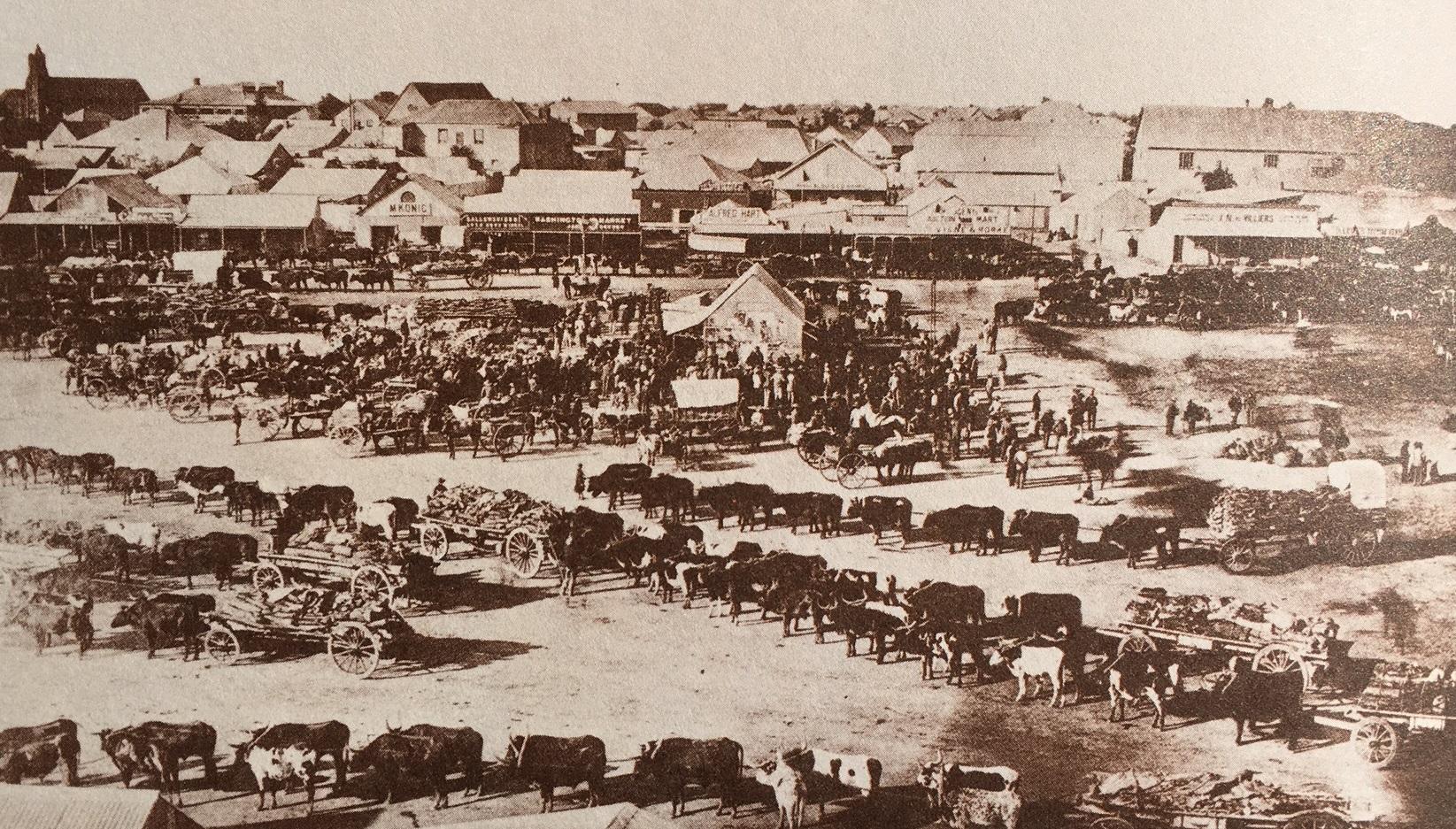

Thus any travel into the hinterland of South Africa was to be overland by foot, on horseback or by ox-wagon – your great great grandfather’s version of a one ton bakkie (pick up or utility). The ox-wagon was the fusion of two cultures – the wagon came from the Dutch settlers and the oxen from the indigenous people, cattle herders known as the Khoikhoi. Without the ox-wagon Kimberley and Johannesburg would never have been built when they were and they would have had to have waited for the railway to arrive; in the case of Kimberley (formerly New Rush) it would have been a long wait of 15 years – 1870-1885.

Market Square Kimberley

The original inhabitants of the Cape had no need of roads as their burdens could be carried by themselves or by their oxen and thus they could walk across the trackless wilderness or follow the animal tracks made by migrating game. The advent of wheeled transportation in the form of the ox-wagon would require roads; even though they were merely trails made by an ox-wagon that others would follow.

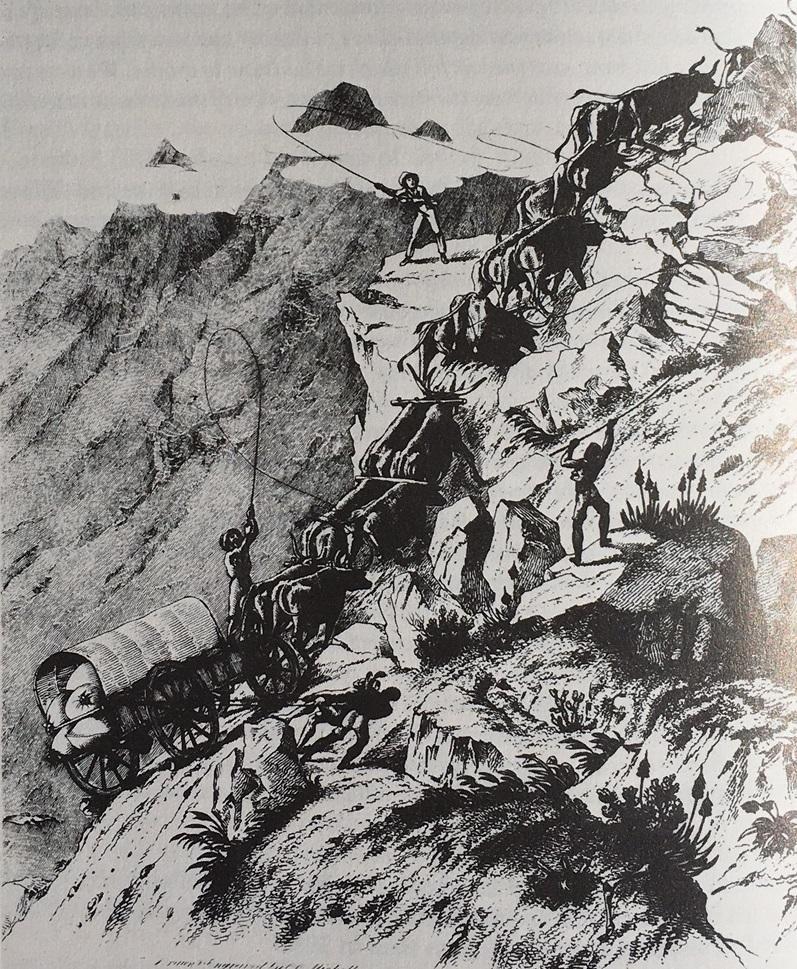

This state of affairs would remain for the duration of the administration of the Cape Colony by the Dutch East India Company (1652-1795), however when the British took power their military took responsibility for improving the mountain passes that led over the mountain ranges which hemmed in the Western Province (i.e. Cape Town, Stellenbosch, Paarl and Franschhoek). The main wagon route eastwards to the Boland and Overberg had to cross the mountains by the notorious Hottentots Holland Kloof Pass, formerly known as the Gantouw Pass (Eland’s path), which followed a track made by game, which the Khoikhoi had followed on foot; to traverse it by ox wagon was an arduous and dangerous undertaking not for the fainthearted and over many years many wagons were cajoled and dragged over a succession of rock ledges at a gradient of one in four. Lady Anne Barnard, who spent five years in the Cape, during Britain’s first occupation (her stay was from March 1797 to January 1802), bore witness to a wagon being hauled over the pass when she wrote “The path was so perpendicular and the jutting rocks over which the wagon had to be pulled, so large in the middle of the road, that we were astonished how it could be accomplished at all, particularly at one pass called The Porch”. The pass served until 1830 when it was circumvented by the first Sir Lowry’s Pass, which was built by the engineer Charles Michell and allowed ox wagons to go over the summit (at 420m above sea level) without damage. The present day four lane highway (N2) which was completed in 1984 follows closely the route of the original pass.

Famous drawing depicting a dramatic ascent by ox wagon (Cape Archives)

Many more passes were to be built at the behest of the British authorities and more was achieved within the first 40 years of British rule (1815-1855) than in the previous 160 years. The name of Bain has a special reverence amongst civil engineers as both Andrew Geddes (father) and Thomas (son) were prolific mountain pass builders. Their passes opened up the interior and many are still in use today and we owe them a great debt of gratitude for what they achieved.

Mountains blocking the path to the interior

The Cape Mountain passes are worthy of their own piece of writing and here only two will be mentioned that were built by Bain the elder and they are the Michell's Pass (1847) and the Bain’s Kloof Pass (1853). Together they opened up a direct route to the north-east and formed part of a now forgotten highway that went from Cape Town via Wellington and Ceres, and then through the Great Karoo by way of Sutherland, Frazerburg and Victoria West. The opening of the Du Toitskloof Pass, in 1949 would relegate this road to a byway with only a part of it being in use today as the R356.

The discovery of diamonds in 1867 in Griqualand (a sparsely inhabited area 600 miles north-east of Cape Town) started a “Rush” by fortune seekers from across the globe. Kimberley would arise and become the hub of the diamond fields and the “Forgotten Highway” became the arterial road to get there. The quickest means was by stagecoach and in the 1870’s a stagecoach drawn by a team of horses or mules (for speed a fresh team was harnessed at the start of each stage, a stage being 20 miles or so) and it would take 7 to 8 days should there be no hold-ups (breakdowns or armed!).

Photograph of an old painting of a stagecoach crossing a river

Travelling by stagecoach may seam romantic whilst watching a “Western”, but in truth it was anything but, it was a journey to be endured rather than enjoyed on a road, which scarcely deserved the name. Nevertheless the road remained essential until the railway had been completed. Kimberley became the driving force of the Cape Colony’s economy and the day that the first train arrived (28th November 1885) was one of great celebration. Thereafter it was thought that stagecoaches and the ox wagons would be outmoded by the train, but as it transpired they were given a new lease of life by the discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand in the early part of 1886. By mid 1886 men were streaming to the new goldfields and they would create a new boom town to be called Johannesburg that needed manpower, mining equipment, building materials for shelter and not least food and drink. The wagon trails would get the people and their provisions there, there was no other way.

References and further reading:

- “A brief history of transport infrastructure in South Africa up to the end of the 20th century” by Dr Malcolm Mitchell (serialised in 10 chapters in the “Civil Engineering” magazine, February to November 2014 - SAICE).

- “A Century of Transport (1860 – 1960): a Record of Achievement of the Ministry of Transport of the Union of South Africa”, published by Da Gama Publications Ltd. Johannesburg, 1960.

- “Towards the Far Horizon – the story of the Ox-wagon in South Africa” by Jose Burman, published by Human & Rousseau 1988.

- “Old Cape Highways” by Dr. E.E. Mossop, published by Maskew Miller Ltd. Cape Town, 1927.

- “Atlas of Southern Africa” published by the Readers Digest, 1984.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.