Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

There is a story of a riot with much blood in the early history of the Dube Township in Soweto. It happened 11 months after the Dube hostel opened its doors on 1 October 1956. The Dube Hostel was the first government hostel in Soweto (then called the South Western Townships).

Dube Hostel (via Google Maps)

The government hostel scheme was for South African permit holders from the then so-called Homelands / Bantustans / rural areas working in Johannesburg on contract since the urbanisation – in this case to Greater Soweto / Alexandra – of South African Blacks was no option.

The first group of Zulu migrants in the Dube Hostel included migrants who used to live in Johannesburg in what the press called locations in the sky. These were so-called 'boys' working as cleaners, gardeners, even manjingelanes (night watch men) and accommodated in rooms provided by their employers – landlords owning the buildings – mainly located at the top of Johannesburg flat and office complexes.

Hostel development was in compliance with the hostel law adopted in 1955 to support the 1950 Groups Areas Act in terms of which all racial groups had to live separately in designated areas. Hostels therefore had to be provided for the mentioned 'boys' – as commonly referred to – also for domestic workers (garden boys and kitchen girls) living in servant’s rooms on the premises of employers. Exceptions for home owners in the suburbs was available at a regular renewal and payment to authorities.

Tour guides please note: Soweto government hostels did not cater for mine workers since mines provided accommodating compounds. If individual mine workers lived in a hostel it was an exception and per private arrangement for individuals by employers.

Township hostels were therefore for men (and women in Orlando West/Mzimhlope Hostel which was ready in 1966) permitted to work in Johannesburg. A contract lasted for 11 months per year and required booking a hostel bed. After the period the migrant had to go back on a month’s leave and so-called call-in as the permit renewal was popularly called. The call-in required documented permission from the homeland authority / tribal chief / rural authority, for another year. And therefore for entrenchment of the psycho-social reality of living without family and tribal support, while children growing up without one parent / role model. Currently migrant labour is entirely at random since enforcement – permits – legally ceased on 12 September 1986 (Regulations published in compliance with Black Communities Development Act 102/94).

The permits and by implication, hostels, were for 'boys' performing essential services like milk deliveries, sewerage works, as stated by a hostel superintendent (see Nakasa, reference list).

The possibility that it established some custom is true. The Jabulani Hostel has been partly converted into single apartments. At the back some applicants are living in caravans, while a group of migrants live in appalling conditions in dilapidated old hostel structures and shacks. A recent fight with shooting killed 6 of these residents in June 2020.

The migrant labour system was and still is entrenched by authorised mining migrant labour systems, also from other African countries – a different story. (The author of this report was one of the researchers involved in a sociological study of accommodation on North West Mines in 2008, but the recommendations requested were not implemented and Marikana happened. Living conditions in rural mines were shocking).

The hostel dwellers in 1956 had to adjust to new conditions and travelling to work by train. Trains were the main mode of transport for Soweto residents at the time. Trains were also infested with tsotsis who were also staff riders (hanging onto the train outside) and also famous for not paying train fare. That is over and above robbing and harassing passengers.

Tsotis at the time, were an anti-social group consisting of younger men of mixed African ethnicities emerging as an identifiable sub-culture of mixed ethnicities since the years 1935/1940. Times were chaotic with lots of migration, a serious slump in the economy after World War II, shacks and homes being greatly overcrowded. Tsotsis spoke tsotsitaal containing some Afrikaans roots. They also dressed different since they wore tight jeans (not a general fashion at the time), caps and takkies, carried knives and sharpened bicycle spokes, viewed work as hlazo (shame). A prison record was regarded as udomo. Although they harassed females, their girlfriends were called tsotsikazi. (Tsotsi-taal was generally spoken in Sophiatown since residents were a mixture of black cultures, so-called Coloured people and more. They were not a criminal sub-group like the Soweto and other tsotsis. Sophiatown residents were forcefully removed to other townships depending on classification, e.g. Coloureds to Westbury, the majority of black to the then newly created township Meadowlands in Soweto).

Deviant tsotsis crowded train entrances, pestered passengers, especially younger females and passengers were robbed, while pickpocketing also happened. Trains in those times were very crowded since workers travelled to and from work and it was easy for tsotsis to rob. On paydays they were very present and also ambushed residents walking from train stations.

African people had no choice but to travel in third class coaches which were poorly maintained and over-crowded. Judging from a review of a short story titled The Dube Train by Can Themba – respected late writer / journalist in the 1950s – the tsotsi behaviour was not challenged where they liked to harass females. Tsotsi fear?

The hostel Zulus, new to spending money on travelling and being tsotsi targets, were building up an anger towards this arrogance. On that day in September their anger spilt over and they started hitting at random on heads of suspected males, e.g. wearing caps. They believed that if you hit a cap, the suspected tsotsi will come out. In the process they hit Russians– big mistake.

The Russians / Marassia were a group of Basotho men originally from Lesotho and rather feared by residents when they wore their traditional attire. Although most of them originally came to work in the gold mines, many seemed to move to employment in industries operating heavy duty machinery requiring physical strength from labourers.

These Basotho men chose the name Russians / Marassia since some volunteered to serve in in World War II of 1939-1945. They believed it was really the fighting skills in war of the Russian Soldiers which defeated the Germans in that war. There is documented history of Marassia who lived in Shantytown in Moroka/CWJ (1945 – 1956), who did sometimes have fights with Zulu residents – both ethnicities known for faction fighting, although there was in general fighting in Shantytown.

Marassia were also famous for being protective of Basotho women and children, also in Shantytown. (Shantytown was an informal settlement built of breeze blocks by the Johannesburg City Council in 1945/6, providing centralised ablution facilities and water, no lighting. It grew and eventually desperate homeless people built shacks from other material. All Shantytown residents were accommodated in formal houses scattered in Soweto townships, in 1956. It was enabled by a R6 million mining loan negotiated by Sir Ernst Oppenheimer. At that stage 200 houses were already built in the Dube Township (1954) with fund from the SA Legion to accommodate black volunteers of World War 2. A few houses were also built in Naledi and it is not on record if that was for Marussia who were in WW2 – it may be since that was a Sotho area).

The Marassia’s traditional outfits consists of Basotho blankets (2 designs). The one design may have stemmed from one group using also the name Japanese which was name dropped due to the devastating Hiroshima bomb, 1945.

Marassia traditionally drape a blanket around the shoulders, fasten it with a large blanket pin – lemau – revealing virtually only the eyes and hat/cap. On the head they wear a Basotho or men’s hat, while carrying a long stick/knobkiere, maybe also hidden sharp weapons. They were also known as majapere, stemming from their alleged love of horsemeat. (Legend has it that eating of horse meat by the Basotho started when King Moshoeshoe and his Basothos were fnable to leave the mountain for some time since it was surrounded by the enemy (Boers?) and ran out of food. They augmented their diet by slaughtering some of the horses and developed a taste for it.

The Marasia did not wear their traditional blankets when going to work. Then they were like ordinary workers and chose clothes like sneakers, caps and jeans. So when the Zulus by mistake hit the heads of Marassia as train passengers, it became a bloody Friday. Instead of a tsotsi coming out or from under the cap, a Basotho did. And Marassias took no nonsense.

Marassia appeared scary and known for fighting with tsotsis in the community and tsotsis were weary of them.

That Friday therefore, was the start of a bloody fight between mainly the hostel Zulus and Marassia while the tsotsis were probably licking their wounds and nursing headaches before re-starting their rule of fear on somewhere far from the Zulus and Marassia.

The blood of the Zulu hostel men’s fighting spirit was kindled. That Saturday they attacked a Basotho funeral procession near the Nndlanzane Station on the way to the graveyard – and that was their second mistake.

Not only Marasia were in the funeral procession which, in compliance with the traditional prescribes, was not small. The mourners were also accompanied by white policemen who opened fire to protect the mourners (only white policemen were armed at the time). Zulu men were killed, more blood flowed.

However, the fighting spirit of the Zulus made them wait for the mourners to return from the graveyard and attacked them again. More blood flowed and more bodies fell on both sides. The Zulu/Marassia fight continued the next day and there were more casualties.

But peace was apparently restored and the Zulus and Marassia, it is rumoured, drank together some time later – however that may be an urban legend.

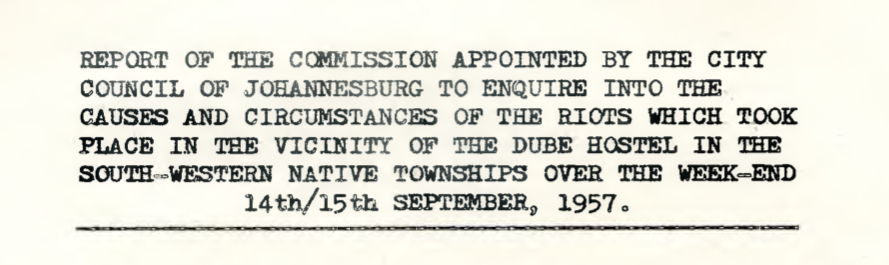

The Johannesburg City Council in charge of Soweto at the time, involved the Institute of Race Relations: ‘…to enquire into the causes and circumstances of the riots which took place in the vicinity of the Dube Hostel in the South Western Townships over the weekend of 14/15 September 1957.’

The Dube Riots Committee produced the 89 page report in March 1958 and it can be consulted at the Institute and Wits University.

The report is available at Historical Papers at the William Cullen Library at Wits (The Heritage Portal)

The question is what happened to the fighting groups as Soweto grew and became a city, South Africa a democracy and the effects of social and political change kicked in further. Have new faces and facts surfaced?

Marassia

In 1956 a Mining House Loan of three million pounds (R6 000 000) secured development of 63 township houses per day (total slightly more than 14 000) in ethnically separated townships – Shantytown completely razed since every family received a house. (A corner of CWJ which accommodated Shantytown, is now home to the famous tourist attraction Oppenheimer Tower in the Oppenheimer Gardens which is also since 1974 home to Credo Mutwa’s Khayalendaba).

Oppenheimer Tower (The Heritage Portal)

Oppenheimer Tower plaque (The Heritage Portal)

The majority of the Marassia apparently went to live in Molapo – not a researched fact. However, good information has it that these guys still periodically don their traditional blankets, wear hats and perform their unique style of dance and song in Phiri, a predominantly Sesotho township.

In 1987 the City Council of Soweto (SCC elected in 1983 in terms of the Black Local Authorities Act 102/1982) was in serious financial difficulties due to the official boycott of rent introduced by the Soweto Civics Association (SCA) in 1986. The SCC’s Executive Committee (Exco) was chaired by a Basotho man Letsatsi Radebe, with a remarkable knowledge of, and contact with Basothos / Marussians. In an attempt to address the problem Exco resolved to employ a number of Marassia to deliver accounts to residents. They believed these men would deliver the accounts, commonly called rent accounts although rent was a small identified component of the debit on the account. The full account therefore included essential services such as street maintenance, refuse removal, clinics/health services, etc.). Exco believed these Basotho’s were ruthless and would not submit to harassment by the so-called siya’inyovas or destroyers. Siya’inyovas were a group of mostly younger residents who formed what they called street committees and employed self-chosen and even less conventional methods to render Soweto ungovernable.

On 26 October 1988 the final national municipal election took place – also in Soweto. The same Sofasonke ruling party – but elected members opposing and due to in-fighting of the Letsatsi group – came into power in Soweto with a voting poll of less than 11%. Exco, with new members and under the new chairmanship of Botana Tshabalala, opposed the previous councillors and their resolutions even if it had merit in city management, displaying limited understanding of their function. They did not like the Marussia who also belonged to an ethnicity they opposed – who therefore had to be deployed, while some resigned. Hopefully they are safe and (those still around) part of occasional weekend Marassia moketes (parties). (Rumours or gossip indicates that the mining experience of Marussia are in the informal Zama Zama mining operations on the Rand. The Zulu word zama, means ‘try’). Those Sofasonke councillors however, failed dismally to govern the city efficiently.

The Soweto Accord was signed on 24 September 1990 between the Trasvaal Provincial Council, 3 Soweto Councils (SCC, Dobsonville and Diepmeadow) to inter alia end the boycott, write off domestic arrears and form the Greater Johannesburg discussion group (lead by Dr Van Zyl Slabbert) to negotiate and plan a new local government dispensation. Apart from failing to govern Soweto effectively, their participation in the chamber seemed of be less successful and serious. They were officially dismissed in compliance with provisions of the BLA on 13 January 1993. At that stage Soweto’s finances were in a mess, also since the 'Black on Black Violence' started in the Nancefield / Difateng Hostel complex, spilling over to the East Rand hostels. Soweto was then placed under administration up to 7 December 1994 (effectively from January 1995) when the new local government dispensation for the Greater Johannesburg kicked in.

Tsotsis

The tsotsi group who were in earlier times quite obvious as an antisocial sub-group which resulted from the history of urbanisation, acculturation and drastic economic and social change – all which resulted in these groups which harassed the community in different ways. The earlier tsotsi groups displayed identifiable anti-social group behaviour and identities, spoke tsotitaal. The ‘tsotsi-taal’ gradually faded as an identity round about 1976.

At the time there was acommonly present a political ideology of liberation for all. It included a developing township lingo spoken by all, in particular those with matric and post-matric education. As an anti-social sub-culture, tsotsis from a complex political, and psycho-social genesis with roots going back to when the first black labourers came, or were recruited, to work in an unsympathetic, hard and less accommodating new Johannesburg after the discovery of gold and growth of the Witwatersrand. New labourers were forced to function in the strange capitalist system and culture without a wider induction. They were separated from the support of the own tribe, forced to live outside the tribal support – to mention only briefly some issues related to complex accelerating social change and industrialisation. True to the same forces tsotsis as a sub-culture undergo changes/adjustments over time. They may however not have obvious characteristics similar to earlier times. However, they are still very present and seem to be more absorbed in gangs of a variety. Analysis therefore needs to be reserved until more current academic studies are available.

A sociological analysis of current gang-cum-tsotsi elements in mainly urban areas is in the domain of academic. Regarding language spoken in Soweto – over and above the 9 indigenous languages and English – is Scamto, or Township Lingo, which is popular with the current generation, although it has become part of the daily vocabulary of all. One good example is the ReaVaya speed bus service. (Rea – ‘we are’ – going, or vaya which stems from the Afrikaans ‘waai’ and ‘vay’ is generally used meaning ‘to go’. This is not at all related to tsotsis or gangsters. It furthermore needs to be emphasised that many newly urbanised migrants of all sexes, especially women, did and still do, adjust and create good homes, became well adapted citizens and form community groups like ma-societies / burial groups, stokvels, prayer groups, and more.

Dube Hostel

The Dube Hostel is still alive and well, judging from their Facebook Page. There are men, women and children living there in spite of a robbed top roof, also units looted from electrical equipment, water taps and more. Looting happened after upgrading by the Gauteng Provincial Government a few years ago. Although the Dube Hostel Facebook displays a variety of pictures, including performances of modern traditional dances, it is hard to tell if any residents are migrant Zulus.

The residents of Dube, like other townships, were not in support of single sex hostels close to families. The hostel Zulus, tsotsis and Marussians then all turned out to become role players in a bloody riot of September 1957 in the Dube Township.

About the author: Estelle was a senior official in city management before and after the 1994 democratic transition. She was in a unique position to be part of official processes like the privatisation of properties, negotiations, participation in important planning and discussions for change, witnessing the rise and fall of the BLA in Soweto, and much more. She has extensive experience as a private property facilitator and as a tourist guide in Soweto for close to 20 years.

References

- Beavon, Keith: Johannesbrg – the making and shaping of the city, University of South Africa, 2004

- Bench Marks: Soweto Report: “What we inhale”. Domestic publication, undated (+- 2018)

- Bonner, P & Seagal, L: SPWETO: A History, Maskew Millar Longman, 1998

- Gittens, Rev. Clarke L G: Soweto … but God? Dorethea Mission, Pretoria, January 1978

- Lewis, Patrick R B: ‘A city within a city’. Privately published paper read on 6 September 1966 by Deputy Chairman of JCC Management Committee

- Molamu, Louis: Tsotsi-taal, a dictionary, University of South Africa, Second Ed. 2004

- Maud, John P R: City Government, Oxford at the Clarion Press, 1938

- Moloi, Godfrey: My Life, Volumes 1&2, Jonathan Ball Publishers, 1991

- Van Zyl, Diko: The Discovery of Wealth, ISBN Don Nelson, 1986

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.