Harold Napier Devitt (he wrote under the name of Napier Devitt) was born in England in 1871 and came to South Africa in 1889 on board the Royal Mail Ship, the Spartan. He tells us he was only 17 years old at the time of his arrival. He explains in the opening chapter of the first volume of his memoirs that he was one of 10 men in a party sponsored by Sir Frederic Young of the Colonial Institute and Sir Henry Pasteur, a City of London man. F C Selous the great African hunter was also on the voyage and thrilled the young Devitt with tales of the African veld.

The Memoirs of Napier Devitt

Devitt was an immigrant to South Africa with the intention of beginning a new life and making his fortune, though in his memoirs published some 45 years after his start to his new life in South Africa, he admits that making a fortune was a "mental illusion".

A few weeks ago I found Young's travel book of his fascinating winter spent in South Africa in 1889 (click here to read my review). Devitt's account of his early days in South Africa as the protege of Young is a companion piece of writing but unlike Young he made his life and career in South Africa. Devitt started by trying his hand at farming but worked only for his food for a year. Then it was a spell at Heidelberg working for an alluvial gold mining operation.

His next move was to Johannesburg and whilst he gives no date for his arrival, it was certainly in the pre-railway years (circa early 1890s). He travelled to Johannesburg from Kimberley by coach and his first impression was one of dust. He mentions arriving in the dust of Commissioner Street and spending his first night at Heights Hotel, paying 25 shillings for a "sheetless bed in a wood and iron unlined building”. He recounts the coach ride, by post cart, from Johannesburg to Pretoria, a four hour journey for a £1 fare, with the first team stop at Orange Grove. The change of mules took 10 minutes and it was on to the next 10 mile stage. The challenges of travel could be a hot axle or a swollen river as there were no bridges.

A memoir is autobiographical; the distinction between memoir and autobiography is that a memoir is entirely selective. It's the author's choice as to what he wishes to reveal and share. Hence Devitt says nothing about his prior life in England, his family or his upbringing. He shaped his memoirs around episodes and impressions of a long life in South Africa, spent mainly as a magistrate.

Devitt studied law and became an articled clerk with HS Caldecott, a Johannesburg lawyer. He passed the Civil Service Law examination in 1907 and joined the public service becoming a magistrate. He went on to spend a quarter of a century on the South African bench in different parts of the old Transvaal including Belfast and Klerksdorp. The Public Service List for 1924 lists H N Devitt as a 2nd Grade Magistrate in the Transvaal, Division A - a status he achieved in 1920. He earned £750 a year.

If Devitt is remembered at all today, he is known as a South African writer of stories and articles. His two volumes of memoirs: Memories of a Magistrate and More Memories of a Magistrate, published in 1934 and 1936 respectively places him within the autobiographical tradition of a singular life. He wrote for The Outspan magazine (this was a popular South African weekly, copied from the British Everybody's magazine. The Outspan was published in Bloemfontein from 1927 until 1957 when it became Personality and then ceased publication under this name at the end of 1965).

Cover of The Outspan Magazine

The magazine style was light and entertaining and articles were short so it is not surprising that the memories are a collection of his early Outspan pieces. The chapters are anecdotal and were meant to amuse. Both volumes of memoirs are collectable and hard to come by. They are worth adding to an Africana library because of the snippets of information and insights into late 19th century and early 20th century South African life, penned by a mature man looking back. He was a shrewd judge of people and human nature.

The two chapters of the first volume of memoirs dealing with the 1922 Strike (chapters 24 and 25) or as he calls it "the 1922 revolution" become useful original source documents. He writes about his experience as press censor and handling 22 to 25 thousand telegraph cables and then having to vet the press proofs at night. He described Johannesburg in 1922 as quickly returning to normal after March 1922 and becoming "gay and golden" once again. His sentence captures the resilience of the town.

Prisoners from the Rand Revolt held at the Wanderers Sports Ground (The Star Pictorial Review: Through the Red Revolt on the Rand. March 1922)

He provides the statistics that there were 199 deaths during the Rand Revolt on both sides and a further 605 wounded. A further chapter recaps the government commission on the causes of the revolution. He was particularly interested in the influence of international communism and that it was the intention of the rebels to proclaim a South African Republic. Of course the real change in political direction came through the ballot box and the election of the 1924 PACT government, but the elite mining houses remained in charge of the gold mines.

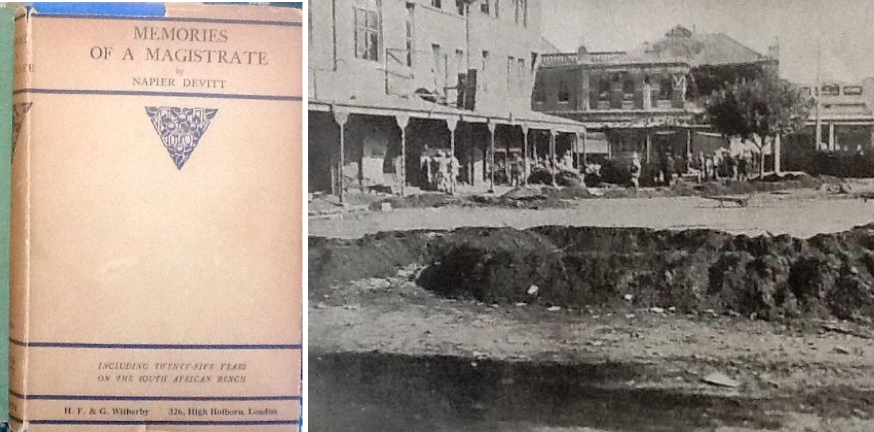

Market Square Fordsburg during the Rand Revolt (The Star Pictorial Review: Through the Red Revolt on the Rand. March 1922)

The purpose of his memoirs was to record his experiences of life, people and political change in South Africa over some 45 years for friends abroad. He published his memoirs at a time when Hertzog was Prime Minister and a coalition of the National Party and the South African Party resulted in a national cabinet. In the wake of the depression years of the 1930s, a coalition government promised economic recovery, active intervention in the economy to address the poor white problem with a nationalist economic agenda.

He showed many of the prejudices and assumptions of his class, background and upbringing. He was an English speaking, white, immigrant South African, fiercely loyal to the British Empire, but there was something of a South African identity emerging. He certainly took the time and trouble to learn Dutch and Afrikaans. Devitt's dream was a united vision of a white South Africa and the diminution in the bitter hostility between English and Afrikaans speaking South Africans. He was conscious of race and his views were paternalistic and segregationist. His prescription for the future of South African politics (and remember this was in the early thirties) was to argue for an abolition of white racial animosities but also to encourage immigration to South Africa from other countries to encourage fresh blood from other lands to settle in South Africa. He was interested in African life in a framework of traditional rule. Native and tribal life was rural. For Devitt the political issue of the thirties was the poor white problem and how government policy could be used to find a solution. The fact that 1936 was the year of the Native Land Act and the extension of land dispossession of black people did not feature in his reflections.

Of what relevance and interest would two volumes of memories published in the thirties have for the reader of the 21st century where the current debate is about expropriation of land without compensation. I think the value of such accounts lies in Devitt being an intelligent, worldly and sympathetic man whose experience of human nature as a magistrate and as someone who had lived through the Anglo-Boer War comes across in his writing. He was clearly on the side of the British. One source says he was an intelligence agent but Devitt gives little away as to what he did in those war years. His insights reveal the political forces that shaped his world and his political thinking. His life and experiences show up the historical fault lines of the 20th century. Here we spot the link between the Boer War, Afrikaner impoverishment because of the war and the origins of the poor white problem and then how an active nationalist framed state policy was used to devise white economic empowerment policies.

De Witt's memoirs are fascinating for three other reasons. Firstly, if you enjoy reading about the trials and tribulations of life in the courtroom, the anecdotes of the legal cases dealt with by a magistrate and the infamous criminal cases (such as the Daisy De Melker case, the Foster Gang or the Von Weltheim murder of Woolf Joel). Devitt was not a Bosman but there is an authenticity to his voice and literary style. Secondly, Devitt provides quick verbal sketches of the leading political figures of his day: Rhodes, Kruger, Louis Botha, Milner, Sammy Marks, Abe Bailey, De La Rey, Lord Selbourne and others. These are first hand accounts and impressions. Finally these books are a rich source of social history. What it was like to live in Johannesburg for example in the 1890s or how the magistrate's courts worked on Government Square.

What does Devitt tell us about life in Johannesburg in the 1890s? His recollections are that life for the ordinary man was far simpler than in the 1930s. Some of his observations surprise. Here is a short extract from his chapter on early Johannesburg:

Wild gambles on the share market were rare and there were few opportunities for the poorish person to make money as there was little of it about. Salaries and wages were low, living cheap, rents lower than today, labour less. For sport the Wanderers Club was the place. Many men were fond of shooting and the winter months saw many shooting parties leave town for the bushveld... Golf was scarcely realized - there was a course in the early nineties which ran up the Kloof beyond the ridge where St John's College now stands. Racing was popular and in Phillips' Sweep, with an office in Commissioner St, everyone had an interest.

An 1897 advert for Johannesburg bicycles and sweepstakes for racing events

He goes on to relate that the British community celebrated the Queen's birthday (i.e. Queen Victoria) with a ball in the Masonic Hall in Jeppe Street. Cycling was popular and most people rode to business on bicycles. Pritchard Street was packed with broughams on the shopping afternoons. Tea rooms were scarce. Quin's baker's shop in Pritchard Street near John Orr's sold tea, also the Anglo-Africa Cafe downstairs. Bars were plentiful. Whisky was 6d a tot (average working man wages were £1 a week and there were 240d in a pound). The principal theatres were the Standard and the Old Gaity and a music hall, but beer halls also provided "light turns". Kerk and Bree Streets were where dozens of brothels could be found. Hotels were unpretentious and cheap.

Devitt mentions the Grand National was built in about 1889 and it was his choice for several visits. In a pre-train era, telegraphs, coaches and wagons were the principal means of communication. He describes Johannesburg as an excitable place with frequent public meetings demanding political rights for the Uitlanders. Devitt has a good sense of humour and provides a couple of anecdotes of Sammy Marks who was evidently a character of early Johannesburg.

Grand National Hotel in the 1890s

Advert for the Grand National Hotel

I have traced an entry for Devitt in the South African Who's Who 1929-30 and another for 1931-32, there is no entry in the South African Dictionary of National Biography despite his extensive range of publications. Devitt's address in Johannesburg was Bedford Road, Yeoville. He was a member of the board of the Rand Aid Association for 9 years and served a term as Vice-President of the Rand Pioneers but he was clearly too young to have earned an entry in the 1906 Men of the Times.

Dewitt was a prolific writer even if largely forgotten today. I have traced the following titles: The Blue Lizard and other stories of Native Life in South Africa (1928), Famous South African Trials (1930), Galloping Jack (1937), The Spell of South Africa (1938), Celebrated South African Crimes (1941), People and Places (1944), Legal Atmospherics - Stories of the Courts of Justice.

The Spell of South Africa Book Cover

Of this selection prices seem to vary widely when titles come up on online auction and sales sites. Galloping Jack appears to be the most elusive and rarest of the titled.

Perhaps historically his most important and enduring work was his 1941 monograph The Concentration Camps in South Africa during the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902, published in 1941. His objective was to counteract what he saw as propaganda about the concentration camps at a time when he felt a more balanced view was necessary to encourage support for the British cause in World War II. His specific interest was in the death rate in the camps and the causes thereof. This small book has become the most collectable of Devitt writings. By 1941 he presumably had retired to the Kowie.

Inside cover of Devitt's most collectable book

According to an online entry for the Killie Campbell Museum, Devitt died in 1954 and some of his papers are held in this museum.

2018 Price Guide: It is difficult to put a price on the Devitt Memoirs as they will seem to be of limited interest and there are no interesting early photographs but expect to pay between R300 and R800. The Concentration Camp booklet is likely to come in at a price of R1800.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.