Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Pious Muslims believe it was prophesied some two and a half centuries ago, that a ‘circle of Islam’ would eventually surround Cape Town. According to local lore, this circle consisting of two dozen ornamental tombs or Kramats of ‘Auliyah’ (friends of Allah), is now complete. These are the mausoleums of important historical figures from the early Cape Muslims brought here as during the rule of the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC) as slaves, convicts, or exiles.

Reputedly, this sacred circle or crescent, safeguards Cape Town and surrounds from natural and other disasters. Many Muslims therefore view these Kramats as places of blessing, where intimacy with God can be attained.

I have been meaning to visit some of these historic Kramats, after reading The History of the Tana Baru and visiting this old Muslim cemetery on the slopes of Signal Hill.

Fortunately, I discovered the Cape Mazaar (Kramat) Society had published a handy, Guide to the Kramats of the Western Cape.

This little booklet is the ideal travelling companion to these Kramats. It contains guidelines on the etiquette for visiting a Kramat, the local term for the tomb of a saint. There are also brief descriptions and histories of the twenty-four Kramats, complete with map and GPS co-ordinates.

A visit to the Kramat of Sheikh Yusuf at Faure, supposedly the most important Muslim tomb in the Western Cape, soon beckoned. My interest was stimulated by discovering Sheikh Yusuf’s life commenced in distant Makassar, on the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia, and sadly ended in exile at Macassar, on the outskirts of Cape Town. His impressive Kramat was designed by the leading early 20th century South African architect, Francis Kaye Kendall, who had just completed the very successful and sympathetic restoration of the manor house at Groot Constantia, following a very destructive fire.

‘Sheikh’ or ‘Shaykh’, a title of respect, means teacher, learned man or venerable older man.

There are many ‘ifs’, ‘buts’ and oral accounts concerning the legend of Sheikh Yusuf, understandably so, since he was a much-revered person, born almost four hundred years ago and who travelled widely for his religious studies and teaching duties.

Fortunately, there are records available of his religious and political activities in the National Archives of the VOC in The Hague. He wrote his literary religious works in three languages, Melayu, Buginese and Arabic and many have been preserved in archives and libraries across the globe. These archival documents enable modern researchers to follow his whereabouts in the East Indies, the Arabian Peninsula, and Indian sub-continent during the 17th century.

According to local Indonesian tradition, Abidin Tadia Tjoesoep (the later Sheikh Yusuf) was born in 1626, to a woman from a village in the South Province of Sulawesi (previously the Celebes).

Map of Sulawesi (Wikipedia)

Little is known of Yusuf’s father other than he appears to have been a village chief of low rank. After Yusuf’s birth, he vanished from the pages of history.

According to some sources, his mother married the ruler of the kingdom of Gowa, Sultan Alaudin, soon after Yusuf’s birth. Mother and son then lived at the court where Yusuf was raised as a Gowan noble.

The Kingdom of Gowa was situated in the south-western peninsular of the island of Sulawesi. In the 16th and early 17th centuries it became the leading regional political and economic entity because its strategic location controlled some of the important spice routes. Eventually, its importance and success would prove its undoing when the VOC defeated Gowa in 1669, to bring it under its sphere of control.

Even as a young man, Sheikh Yusuf was dedicated to Islamic learning and by 1644, aged eighteen, he prepared to continue with further religious studies abroad.

For the next twenty years he studied in Gujarat, Yemen, Mecca, Medina, and Damascus.

In 1664, he returned to the East Indies, but probably avoided Gowa, as this kingdom was in turmoil because of its imminent and bitter conflict with the VOC. Instead, Sheikh Yusuf stepped ashore at the Sultanate of Banten (formerly Bantam) in Western Java. Here he established himself at the court of Sultan Ageng and married one of the Sultan’s female relatives. By the late 1670’s he had become the foremost religious authority and teacher in the sultanate. Over time he also developed into one of the Sultan’s most trusted political advisors.

Unfortunately, by 1682, a power struggle had developed between Sultan Ageng and his oldest son, who colluded with the VOC to depose his father.

Sheikh Yusuf sided with Ageng and his supporters but when Ageng surrendered, Sheikh Yusuf took to the forests and mountains to continue resistance to the new Sultan and VOC. By late 1683, when Sheikh Yusuf and his dwindling band of supporters were in desperate straits, he surrendered on promise of a pardon.

The promise of a pardon by a Dutch officer was not fully honoured by the VOC. For a while Sheikh Yusuf was imprisoned in the castle in Batavia, now Jakarta, where he was treated with considerable dignity by the Dutch authorities.

Andries Beeckman The Castle of Batavia, c. 1661, oil on canvas, (Rijksmuseum)

However, in 1684, fearing that this revered Islamic scholar would incite his supporters against the VOC, the Governor General and the Council of the Indies banished him to the VOC castle in Colombo, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), where he remained until 1694.

By 1689, this pious scholar and erstwhile fierce opponent to VOC rule seemed to have become an ailing and exhausted old man. A Dutch transcribed letter in the National Archives in The Hague, quotes him begging the VOC for forgiveness and pleading for his return to Batavia. Perhaps, wary of some duplicity, the Council of the Indies ordered that his request be ignored, and he remained in exile in Colombo.

Sheikh Yusuf was then banished to the Cape of Good Hope, where there would be no possibility of escape or contact with his followers and supporters in the East Indies.

Together, with his retinue of two wives, twelve children, two slave girls, twelve Imams (religious scholars) and followers, totalling 49 people, they arrived in Cape Town in 1694, on board of the Dutch sailing vessel De Voetboog.

According to oral legend, when the supply of drinking water on this ship was exhausted, it was replenished from a spring of fresh water that appeared in the middle of the sea, because of Sheikh Yusuf’s prayers.

At the Cape he was also treated with respect by Governor Simon van der Stel. For his subsistence at the Cape, the VOC granted Sheikh Yusuf a stipend of twelve rix-dollars a month.

Sheikh Yusuf and his followers were settled at the mouth the Eerste river near the Rev. Petrus Kolben’s farm Zandvliet, where they lived for the following ten years. In later years this area became known as Faure.

This isolated site was probably selected to minimise their social contact with the local Muslim community. Apparently, this became a sanctuary for escaping slaves and according to oral history this was where the first cohesive Muslim community in the Cape was established.

When Sheikh Yusuf died on 23 April 1699, he was buried on a low hill overlooking the countryside, not far from the mouth of the Eerste river in False Bay. The area towards the nearby coastline became known as the Macasssar Downs, in memory of his birthplace.

Though many believe that Shaykh Yusuf still lies buried at Faure, other sources suggest that his remains were conveyed to his native land early in the eighteenth century.

Entrance to Sheikh Yusuf’s ko’bang (tomb) at Lakiung, Sulawesi.

Instructions from the Council of XVII were received at the Cape on 26 February 1704, permitting his wife, their children, and other members of their entourage to return to the East Indies, (present day Indonesia). They further directed that the remains of Sheikh Yusuf were to be unobtrusively exhumed to allow the family to return them to the East Indies.

According to this version, on 5 October 1704, the Dutch sailing ship De Spiegel departed Table Bay with the remains of Sheikh Yusuf. Anchoring at Batavia on 10 December, his remains were taken to Makassar, where they were reinterred at Lakiung in Ujung Pandang. Above his new grave, a Kramat, or ko’bang as it is termed in Indonesia, was erected by the Chinese builder Diu Kian Kiu.

Grave of Sheikh Yusuf in the ko’bang at Sulawesi

But irrespective of whether his remains were repatriated or not, his Kramat at Macassar remains the most important site of Islamic pilgrimage in South Africa. When we arrived there at lunch time, a religious ceremony was taking place and we were both touched when one of the organisers offered us a light meal and bottled water.

Upon entering the grounds of the Sheikh Yusuf’s Kramat, you pass the dargah (shrine) containing the burial sites of four followers, most likely Imams, who accompanied him to Macassar.

One plaque reads, ‘The dargah (shrine) of ashabat (companions) of Saint Sheikh Yusuf (Caleran Tuanse) of Macassar. Here lie the remains of four of forty-nine faithful followers who after serving in the Bantam war of 1682-1683, arrived with Sheikh Yusuf at the Cape from Ceylon, in the ship Voetboog in the year 1694. This commemoration tablet was erected during the Great War on 8 January 1918, by Hajee Sullaiman Shahmahomed. Senior Trustee.’ The honorific title of ‘Hajee’ or ‘Haji’, is given to a Muslim who has successfully completed the Hajj to Mecca.

Dargah (shrine) of the four companions of Sheikh Yusuf at Macassar/Faure. (SJ de Klerk)

Sullaiman Shamahomed (1859-1929), a successful Indian businessman, originally from Gujerat, purchased the land where the Kramat is situated on a public auction in 1908, following the bankruptcy of the previous owner.

In 1925, he commissioned the eminent South African architect Francis Kaye Kendall (1870-1948), former Senior Partner of Herbert Baker, to design a new Kramat to cover the tomb.

Ramparts and cannons symbolise the wars in which Sheikh Yusuf participated (SJ de Klerk)

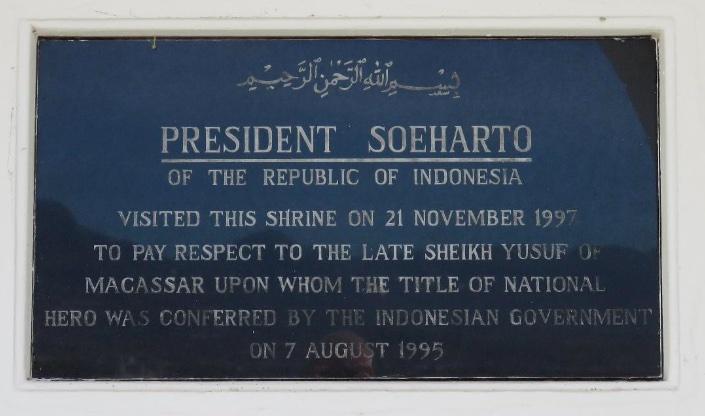

An interesting plaque commemorates the visit of Soeharto, the erstwhile President of the Republic of Indonesia to this site on 21 November 1997. Two years prior, the Indonesian Government had conferred the title of National Hero on Sheikh Yusuf.

The plaque (SJ de Klerk)

It is appropriate to conclude with the comments of the late Professor Adrianus van Selms (1906-1984), who filled the chair of Semitic languages at the University of Pretoria.

He authored the sympathetic biography of Sheikh Yusuf in the Dictionary of South African Biography:

After two and a half centuries it is very difficult to determine what the secret of Yusuf’s great influence was. Undoubtedly his was an attractive and imposing personality; he was sophisticated and brave, energetic and intelligent. The most important element in his relations with his fellow Muslims lies, however, in religion. This is indicated by his title, sheikh, which is bestowed by Muslims on great religious leaders. He was not only a mystic, but through his teachings, introduced his followers to experiences similar to his own. Thus, he had a profound influence on their spiritual life, an influence impervious to political defeat and exile. To Yusuf is also attributed Allah’s traditional saying: ‘Man is my secret being, and I am his’.

About the author: SJ De Klerk held many senior positions in HR during a distinguished career in the private sector. Since retiring he has dedicated time and resources to researching, exploring and writing about South African history.

Sources

- Dangor S. E. 1981. A Critical Biography of Sheikh Yusuf. Thesis for MA degree. https://researchspace.ukzn.ac.za

- Davids A. 1985. The History of the Tana Baru. Intergrafis (Pty) Ltd., Cape Town.

- Davids A. 1980. The Mosques of the Bo-Kaap – A Social History of Islam at the Cape. The South African Institute of Arabic and Islamic Research, Athlone, Cape.

- Da Costa Y. & Davids A. 1994. Pages from Cape Muslim History. Shuter & Shuter (Pty) Ltd., Pietermaritzburg.

- De Kock W. J. (Editor). Sheikh Yussuf in Dictionary of South African Biography. Nasionale Boekhandel, Cape Town.

- Du Plessis I. D. 1972. The Cape Malays. A. A Balkema, Cape Town.

- Fransen H. 2004. The Old Buildings of the Cape. Jonathan Ball Publishers, Jeppestown.

- Gibson T. 2001. The Legacy of Shaykh Yusuf in South Sulawesi. http://www.academia.edu/ark

- Jaffer M. (Editor). 2001. Guide to the Kramats of the Western Cape. Published by Cape Mazaar (Kramat) Society. FA Print.

- Jappie S. 2018. Between Makassars: Site, story, and the Transoceanic Afterlives of Shaykh Yusuf of Makassar. Dissertation for PhD. http://arks.princeton.edu/ark

- Schoeman K. 2009. Handelsryk in die Ooste – Die wêreld van die VOC, 1619-1688. Potea Boekhuis, Pretoria.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.