Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Most scholars, historians and authors have concentrated on the battle for the British camp that was fought on the eastern slopes of Isandlwana, Mountain on 22 January 1879, attempting to analyze it ad nauseum every which way possible. What most ignore is that much, if not most, of the action actually took place on the western and northern sides of the mountain on the Rorke’s Drift or Fugitives, side.

Such actions include the loss of the two remaining artillery pieces of N5 Battery when they fell into a donga; Colonel Durnford’s Last Stand; the graves of Captain George Shepstone and his men of the fleeing Natal Native Horse on the western slopes of the mountain and the battle for the aManzimnyama Drift.

The British are very sensitive about two things above all else – losing (or, in Army-speak, misplacing) their artillery pieces and secondly, losing their Colours to the enemy. Both of these horrendous disasters occurred at Isandlwana. To put it in perspective, the Regiment’s favourite sport of the seduction of the Colonel’s wife by one of the other officers, for example, comes way down on the list of priorities.

The Diehard re-enactment team on site with the colours

Two of the 7 pounder RML cannon of N5 Battery had been left behind in the camp that morning. The other four were taken by Lord Chelmsford on his reconnaissance mission to Hlazakazi earlier on that day. When the camp was overrun, the remaining artillerymen fled with their guns along the line of least resistance (i.e. where there were no Zulus ... yet) along what became known as the Fugitive’s Trail. They encountered a deep donga across their path, and in desperation attempted to jump both guns across the gap. Needless to say, the gap was too wide and the guns fell to the bottom of the donga and their minders and horses were slaughtered by the Zulus.

In 2001 the University of Glasgow was granted permission to do an archaeological dig at Isandlwana in an attempt to ascertain once and for all where well-known incidents during the battle had occurred.

One of these was to find the exact spot where the guns had been lost (oops – should I say misplaced?). The team became very excited about one particular location and excavated a hole into an earthen berm which formed part of the wall of an old dam. One often forgets that Isandlwana was quite heavily populated up until the 1980’s and the people were only moved off the site when the area became a Nature Reserve. For example, a school once stood on the spot which the Zulu Monument now occupies.

So, furious digging later, the team discovered that they had, in fact, been digging up an old refuse pit instead! They never did find the exact spot where the guns were lost.

The other fish bone-stuck-in--the-throat was the loss of the Colours. Each Battalion of the 24th Regiment had two Colours or flags – the Queen’s Colour (or Union flag) and the Regimental Colour, on which were recorded the Battalion’s Battle Honours.

The 1st Battalion had left its Regimental Colour at the forward base at Helpmekaar, so that was safe. But not so the Queen’s Colour. The attempt to save it from falling into the hands of the enemy is an epic to which we will return in detail later. Everyone forgets that the 2nd Battalion lost both its Colours. I guess that they are still out there somewhere in Zululand, perhaps converted into a curtain or table cloth? It has been my quest for the last 30 years to attempt to find them – alas, with no success so far.

The responsibility for the safe-guarding of the 1st Battalion’s Colours rested with the Adjutant, Lieutenant Teighnmouth Melvill.

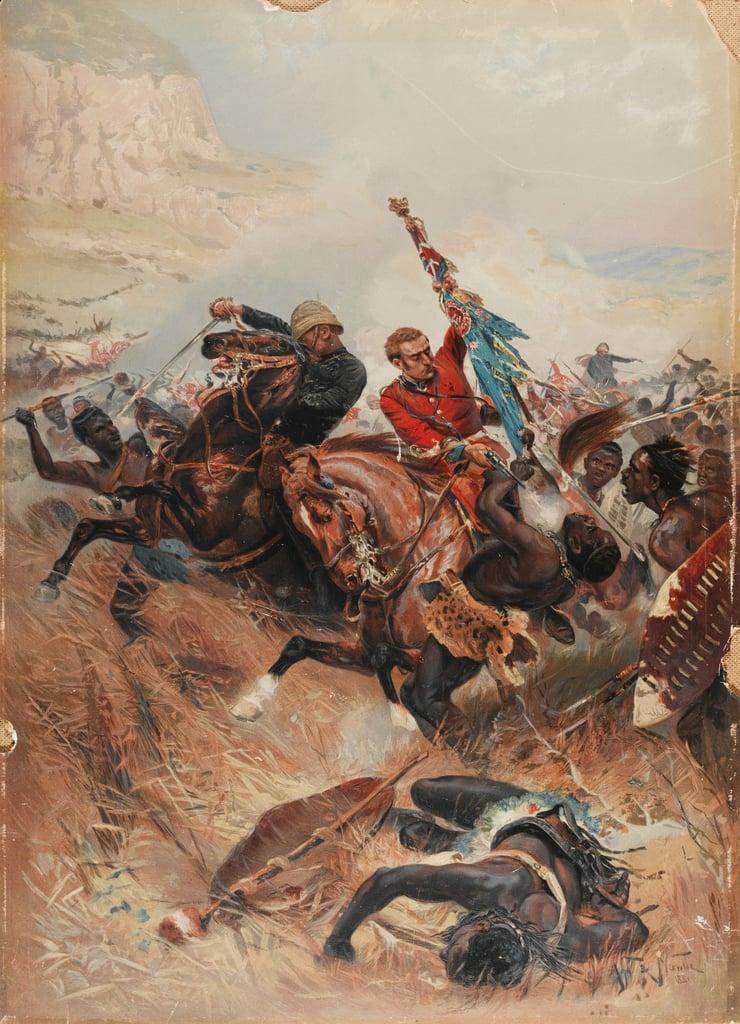

Lieutenants Melvill and Coghill Saving the Colours (Alphonse De Neuville)

Historians have often argued that Melvill used the safekeeping of the Queen’s Colour as an excuse to desert and flee to safer pastures with it. I don’t believe it for a second. I believe that Melvill would have climbed to a high feature with the Colour when he saw that the camp was in imminent danger of being overrun, and used it in an attempt to rally the troops. When that was unsuccessful, his duty was clear – save it from falling into the hands of the Zulus at all costs.

During the COVID lockdown in 2020, Charles Aikenhead, the former owner of Rorke’s Drift Hotel and I were shown a “new” grave on the Fugitive’s Trail right next to the current road leading to Isandlwana from the aManzimnyama Drift by Shane Evans of Isandlwana Lodge. Charles brought his brush-cutter along and we cleaned up, hacked down and spruced up the place –almost certainly the first maintenance it has seen in over a century.

Locating the grave (Talana Museum)

This previously undiscovered grave led me to revisit some of the standard texts. Contrary to legend, we now know that the Zulu right horn was already deploying by sunrise (04:45) on that fateful morning of 22 January 1879. Captain A.I. Barry’s Number 5 Company 2/3 Natal Native Contingent had been sent up to Magaga knoll early that morning in response to a sighting of Zulus in the vicinity. Lieutenant Walter Higginson had ridden up to the knoll with Sergeant Major Williams later that morning (about 08:00) to make contact with Captain Barry’s command.

Cameron Simpson quotes Lieutenant Higginson’s Isandlwana report that was published in the National Archives document, WO33/34 as an enclosure. In this report, Higginson and Williams found:

Capt Barry & Lieut Vereker watching a large force of about 5,000 which had gone on around behind the Isandhlwana (sic) hill. I remained about three quarters of an hour & then returned to Camp.

Lieutenant John Chard corroborates that conclusion. According to “The Silver Wreath”, Chard’s account states in part that:

On the morning of the 22nd January, I put the Corporal and the three Sappers in the empty wagon, with their field kits, to take them to the camp of the 3rd. Column; and also rode out myself. The road was very heavy in some places, and the wagon went slowly, so I rode out in advance, arrived at the Isandlwana camp, went to the Head Quarters Tent, and got a copy of the orders as affecting me.

An N.C.O. of the 24th lent me a field glass…… and (I) could see the enemy moving on the distant hills, and apparently in great force. Large numbers of them moving to my left, until the lion hill of Isandlwana, on my left as I looked at them, hid them from my view. The idea struck me that they might be moving in the direction between the camp and Rorke’s Drift and prevent my getting back, and also that they might be going to make a dash at the ponts.

So, what was the Zulu purpose for being there so early? Laband and Thompson show that the elements of the right horn were the uNokhenke (who hugged the western slopes of the mountain and were ultimately responsible for annihilating Shepstone’s little force); the uDududu, iMbube and iSanqu amabutho. George Chadwick states that the uThulwana, uDloko and iNdluyengwe swung even further to the west.

Contrary to popular belief, I believe that the Zulu’s main objective was NOT the camp and its cornucopia of treasures. First prize was the column’s livestock, let out to graze to the west of the mountain, down the slopes towards the aManzimnyama River. If one does a quick calculation, the 300 or so wagons and carts would, on average, have required a full span of 16 oxen to pull them, given that it was the rainy season. In difficult conditions, this may have increased to a double span of 32 animals. Add those animals brought along for slaughter as rations (about 40 per day), and those captured from the Zulus along the way, then they must have numbered over 6000 at the very least. This, such a glittering prize for a pastoral people who were obsessed with cattle, was irresistible.

This is corroborated by eye witness accounts from Nourse and Harry Davies. When the Zulu right horn finally made it around the back of Isandlwana, whether by accident, design or just plain enthusiasm, they drove some of these draft and slaughter oxen in a panic stricken stampede before them. According to Nourse’s later testimony:

Good God! What a sight it was. By the road that runs between the hill and the kopje came a huge mob of maddened cattle, followed by a huge swarm of Zulus.

According to Davies:

I saw a great many wagon drivers, leaders and many others leaving the camp … making direct for the river. I saw … Zulus pouring down in great numbers at the back of Isandlwana hill thereby cutting off our retreat.

… the green grass was red with the running blood and the veld was slippery, for it was covered with the brains and entrails of the slain. The bodies of black and white were lying mixed up together with the carcasses of horses, oxen and mules.

Far from being peeved that they had missed out on most of the action and had therefore decided to disobey orders by continuing on to Rorke’s Drift, then, these amaButho, in terms of Zulu thinking anyway, had been the most successful of the lot.

Which also answers another question posed by many scholars – how did the Zulu amaButho who attacked Rorke’s Drift, the uThulwana, iNdluyengwe, uDloko and inDlondlo, cover the 12 or so miles from Isandlwana to Rorke’s Drift over very rough ground within three hours? The answer is simple – they started off much earlier than previously thought and, by the time some of them decided to carry on, were already nearly halfway there. That conclusion notwithstanding, they must still have been absolutely exhausted on arrival at the mission station, thus contributing to their inept handling of the attack.

So, let us return to the lonely, “newly discovered” grave and look towards the aManzimnyama River. A couple of hundred yards further on towards the drift, there is a huge mound topped with whitewashed stones, right next to the modern bridge, which marks the original drift over the river. Historians have always assumed that, underneath it, lie the remains of those British and Colonial forces who were working at the drift when they were caught by surprise by elements of the right horn.

Picture the scene. Although the drift itself has a nice, solid rocky bottom, the exit was churned to a quagmire by every wagon. Gangs of chanting, singing native “pioneers” and labourers were kept busy cutting down logs and heaving stones across to corduroy the bank. Bull whips cracked continuously over the heads of the straining spans of oxen, while dozens of men strained and pushed the wagons through the drift. The guarding Company takes up position under any available shade overlooking the drift, smoking and chatting and damn glad that they are not in the same predicament.

According to Standing Orders, at least one Company of Regular soldiers would have been detailed to guard this portion of the vital supply line. Just who this was has always been a matter of conjecture. Some historians claim that it was Lieutenant Edgar Oliphant Anstey’s Company, 1/24th Regiment. However, “The Times” of 22 April 1879 contradicts this, claiming that Anstey’s body was found by Lieutenant Armitage on the eastern side of the nek and was buried by Major Black.

A crackle of shots and the “boom” of the cannon attracts their attention. Everyone is shushed, straining for any sounds of a struggle. There it goes again. Smiles break out. This is better than pushing bogged-down wagons. Presumably the guys in the main camp are giving the savages a hiding? Work stops. Oxen stir restlessly. A short while later, they hear distant chanting. Ears are cocked once again. There is a rumble like an approaching train, and then suddenly hundreds of warriors burst out of the ravine upstream, taking the men completely by surprise.

Chaos and pandemonium reign. The oxen stampede, traces hopelessly entangled, dragging bits of smashed wagons after them. Other wagons overturn in the river. The native workers flee. Those too slow are speared to death. The soldiers form square, organised volley fire keeping the Zulus temporarily at bay. But the pressure of numbers slowly forces the square to back-peddle downriver, dropping men in twos and threes all the way. Just around the bend, a large ravine runs into the aManzimnyama on the eastern bank. This breaks up the integrity of the square as men scramble desperately through the mud to get to the top of the ridge. Their concentrated firepower and command and control is lost, and they are picked off one by one.

Painting of a British infantry square (National Army Museum)

The victorious Zulus strip and mutilate the dead. A number of them are told off to round up the cattle and begin driving them back further into Zululand. Some of the hot heads decide that, since this was so easy, then the garrison at Rorke’s Drift, just over the hill, will be easy meat. And off they go.

Today, a number of whitewashed cairns stand guard on the ridge. Close your eyes and you can sense the atmosphere of frenzied desperation and, now, melancholy.

And every once in a while, we find a new one, and one more missing piece slots into the jigsaw puzzle.

Main image: Coffin Rock, Fugitive's Drift (Pam McFadden)

About the author: Pat Rundgren was born in Kenya and grew up in what was then Bechuanaland and Rhodesia. He has nearly 10 years infantry experience as a former member of the Rhodesian Security Services. He is passionate about and has a deep knowledge of the battles, the bush and Zulu culture. He has written numerous articles on military subjects and militaria collecting for overseas publications, has contributed to several books and is currently busy with his eighth book. His wide ranging knowledge and over 20 years guiding experience and unique story telling will bring events alive to his listeners. His books “What REALLY happened at Rorke’s Drift?” and on Isandlwana and Talana have gone into a number of reprints. He is a collector of militaria with special focus on medals. He also organises and conducts tours around the battlefields of KwaZulu-Natal and tours into Zululand to experience traditional and authentic Zulu culture and life style. Pat is currently the Chairperson of the Talana Museum Board of Trustees and one of the volunteer researchers.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.