Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

It’s always a thrill to meet up with someone who has specifically come thousands of miles to the KZN battlefields to trace where their ancestors fought so long ago. On 17 February 2016, I had the privilege of meeting the Michell family, from Edington in Somerset. Simon Michell was born in Zimbabwe, which gave us immediate commonality. But even better, Simon’s ancestor, Captain Charles Michell, had fought in the Zulu War of 1879, and Simon had the campaign medal and a studio portrait of Charles wearing it to prove it. Simon and Bridget’s purpose was to visit the place where Charles’ unit, the 3/60th Rifles (King’s Royal Rifles), had seen action.

Alas, the KRR did not fight anywhere in the Dundee area during the Zulu War. They arrived just in time to be part of the southern column, which fought at the battle of Gingindlovu on 2 April 1879, on their way to relieve the garrison, which had been bottled up in the mission station in the town of Eshowe for some months. We thus did not have the time to visit the actual site of the battle, but had a great day out at Isandlwana and Rorke’s Drift none the less.

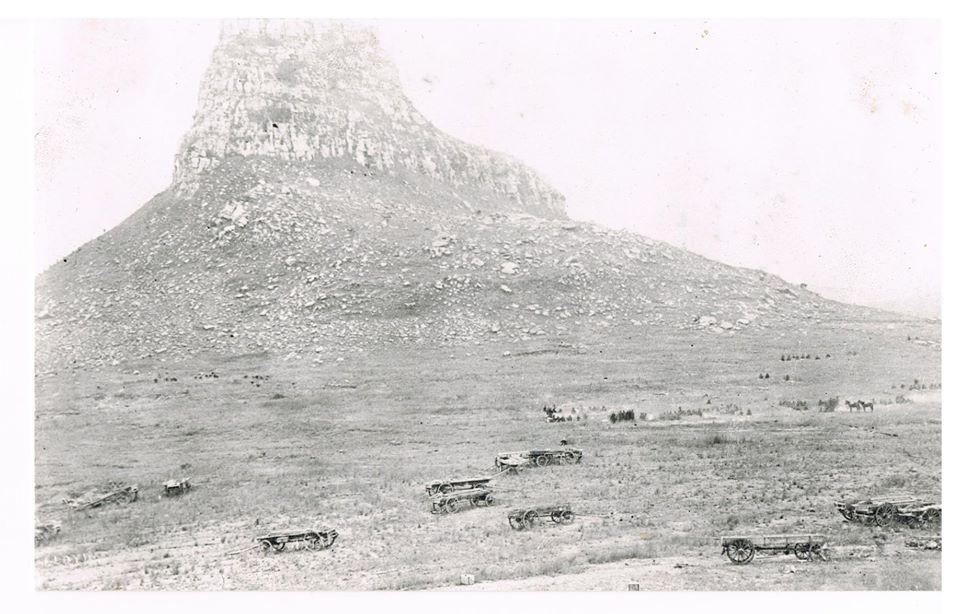

Old photo of Isandlwana Hill (Talana Museum)

Simon provided the basics. Charles Michell was born on 17 February 1849, the son of J. Michell J.P., D.L. of Darlington. He married Louisa Orde Powlett, the daughter of the Honourable and Reverend T. Orde Powlett, in 1883. He was educated at Haileybury School, Trevelyan House 1862-1867, where he captained the school cricket team. That accomplishment, more than anything else, probably assured his successful entry into the Army. Plus the fact that his Great Uncle, Edward, had fought at Waterloo with the 1/52 Foot may have helped.

However, I promised Simon that I would do a bit of research about the 3/60th., and here’s what I found.

Charles Michell had joined the 60th Rifles as an Ensign in 1867, and so would have been a Lieutenant at the battle of Gingindlovu. This battle occurred in what might be termed the second phase of the Zulu War, once the authorities had recovered from the panic caused by the bloodbath at Isandlwana and were in a position to mop up loose ends before the final showdown at Ulundi on 04 July 1879.

60th Rifles in action (British Battles)

The British fought in their traditional square formation at the battle of Gingindlovu, with the 60th Rifles taking position on the northern face of the square. According to Castle and Knight, “the main Zulu body split into columns, then crossed the Nyezane (River) at two drifts a mile apart; and, as it advanced up the slopes towards the laager, it fanned out into the traditional chest and horns attack formation. The order to hold fire until the enemy were within 300 yards condemned the troops at the front of the square to the nerve wracking spectacle of the Zulus deploying to attack without a shot being fired to stop them. It was a sight that was to strain the nerves of the untried men of the 60th.

Repulse of the Zulu attack at the Battle of Gingindlovu (British Battles)

According to John Dunn, “I noticed that the bullets of the volleys fired by the soldiers were striking the ground a long way beyond their mark, and on looking at their rifles I found that they still had the long range sights up, and that they were firing wildly in any direction. I then called Lord Chelmsford, asking for him to give orders for lowering the sights. This was done, and the soldiers began to drop the enemy and consequently check the advance”.

According to Wilkinson, there were some marksmen among the 60th, with one man dropping four running Zulus at 400 yards with consecutive shots.

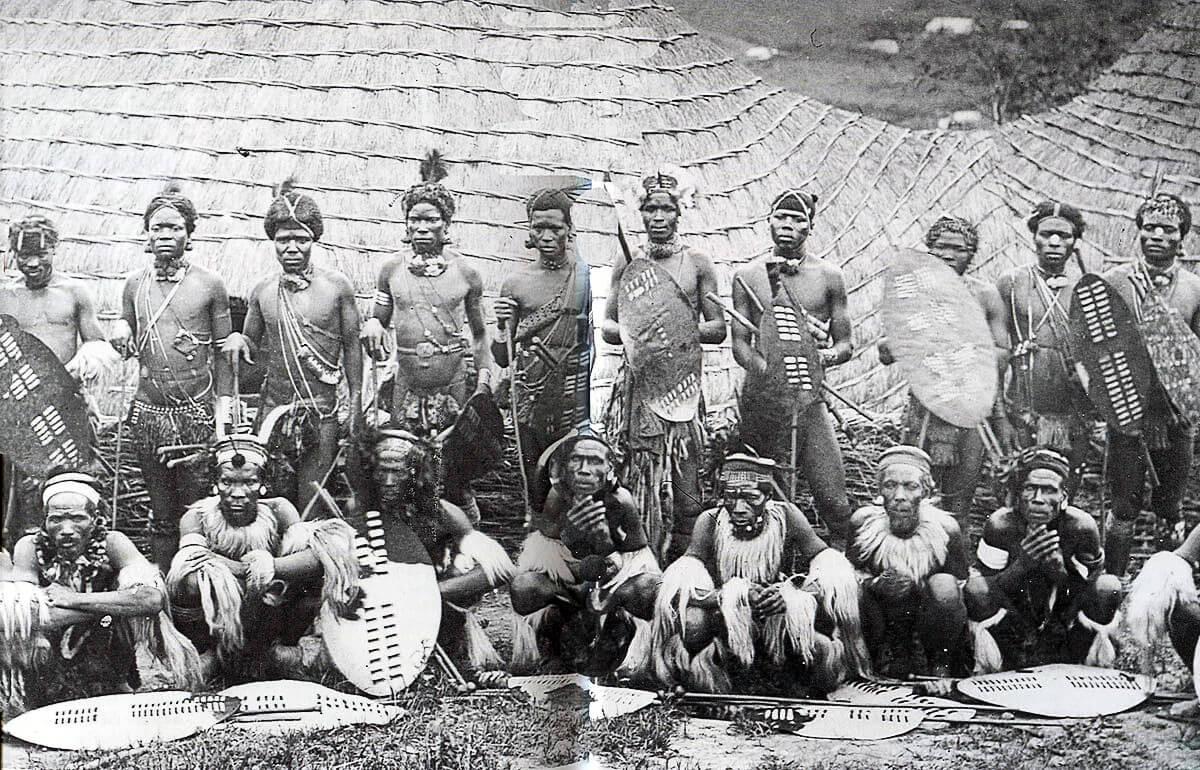

Zulu Warriors at the Battle of Gingindlovu (British Battles)

“The attack never-the-less apparently provoked a crisis among the 60th. The Zulu fire was extremely heavy but, as usual, inaccurate and mostly high. We had some narrow escapes; one officer of ours received a shot in his ammunition pouch, and another officer, Lieutenant R.H. Gunning, had part of his rifle carried away as he was aiming”.

One of the principles of fighting in a square is that the restricted perimeter of such a defensive formation denies savage warriors what they need most in order to deploy their superior numbers – space. If one can reduce the surface area over which the enemy has to work, then vast numbers of men can be channeled into ever diminishing space, with the result that they bunch up and become un-missable targets. In most cases, then, a victory is assured. So long as one doesn’t run out of ammunition! And that is precisely what happened at Gingindlovu.

There is a picture in Morris’ book on page 417 showing men of the 60th Rifles escorting King Cetshwayo and several of his wives and attendants into Sir Garnet Wolseley’s camp at Ulundi on 31 August 1879.

The King’s capture marked the end of the first Zulu War, and the captains and kings duly departed. Those who took part were duly awarded the South Africa Medal with “1879” bar. Forsyth’s Medal Roll records that Lieutenant C. Michell was indeed entitled to the medal.

The 3/60th was one of the units left behind after the Zulu War in order to keep South Africa pacified. The Boers, sworn enemies of the Zulus, had been invited to take part in the war, but had, somewhat surprisingly, demurred. In hindsight, the sight of their two greatest enemies grinding each other to dust must have been most pleasing to the Boers, who awaited the outcome with interest. They assumed, however, that the Empire would eventually triumph. When that happened, the Boers then intended to extend the struggle to the fed-up and wanting-to-go-home British garrisons all over the Transvaal.

The first Anglo Boer War, which broke out on 20th December 1880 by the ambush of the 94th Regiment (Connaught Rangers) at Bronkhorstspruit, ended in disaster for the British. Both sides then rushed to the passes over Laing’s Nek, just north of Newcastle in Natal, which guarded the lines of communication between Natal and the Transvaal. Here, the newly promoted Captain Charles Michell found himself caught up in the battle of Laing’s Nek on 20 January 1881, where the 60th mainly supported the withdrawal of the 58th Regiment after their suicidal charge up an open, grassy slope had failed.

However, the KRR were again in action at Schuinshoogte some 11 days later on 8 February 1881. General Colley had been anxious to protect his supply line from Mount Prospect to Newcastle, and consequently sent out a force to clear the road. After having crossed the Ingogo River, where Colley prudently left two guns and one company of the 3/60th to guard the drift, the remainder of the force made their way up a gradual slope towards a ridge known as Schuinshoogte, where a Boer force awaited in ambush. Taking cover amongst the rocks on the summit, the detachment fought through most of the day, drenched by squalls of rain.

The KRR particularly distinguishing themselves by volunteering to man the guns after most of the artillerymen had been shot down. Ian Castle describes what he calls “appalling casualties” suffered mostly by the Rifles when a half company was ordered out wide on the left in order to foil a Boer attempt to outflank the British position. “Led into position by Colley’s Military Secretary, Captain J.C. MacGregor, the men suffered terribly but held onto their exposed position”.

The detachment was able to disengage after nightfall and retired back to their base camp, having to ford the swollen Ingogo River to do so.

However, worse was to come. General Colley inexplicably decided to occupy Majuba Mountain on 27 February. His reasons for doing so are unknown, since he took no-one into his confidence and gave his life in the battle. His occupation of the hill gained no strategic or tactical advantage. It was too far away from the Boer lines to pose them any danger, and the men of the Gordon Highlanders, so beautifully silhouetted on the skyline, were easy targets for Boers who had crept closer under cover of dead ground. Once the Highlanders had been driven back from the forward crest and could no longer see their attackers, the Boers could climb the hill with impunity, and the outcome was a foregone conclusion. Luckily for the 3/60th, they were not involved in this operation.

Majuba Cemetery (A Winter Tour of South Africa)

Since the British suffered four defeats in the space of two months, no campaign medal was ever issued for the First Anglo Boer War, and thus Charles Michell was never awarded a second medal to complete his entitlement.

Charles Michell retired in 1882 and died on 25 January 1900.

It never ceases to thrill me how a little piece of silver can be the trigger to resuscitate an old veteran who died over a century ago. Now that’s what makes battlefield guiding so great – you get to meet interesting and really nice people as well as to learn something new.

Main image: British Square at the Battle of Gingindlovu via British Battles

About the author: Pat Rundgren was born in Kenya and grew up in what was then Bechuanaland and Rhodesia. He has nearly 10 years infantry experience as a former member of the Rhodesian Security Services. He is passionate about and has a deep knowledge of the battles, the bush and Zulu culture. He has written numerous articles on military subjects and militaria collecting for overseas publications, has contributed to several books and is currently busy with his eighth book. His wide ranging knowledge and over 20 years guiding experience and unique story telling will bring events alive to his listeners. His books “What REALLY happened at Rorke’s Drift?” and on Isandlwana and Talana have gone into a number of reprints. He is a collector of militaria with special focus on medals. He also organises and conducts tours around the battlefields of KwaZulu-Natal and tours into Zululand to experience traditional and authentic Zulu culture and life style. Pat is currently the Chairperson of the Talana Museum Board of Trustees and one of the volunteer researchers.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.