Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

During mid-2019, an exceptional Anglo-Boer War (1899 – 1902) collection of artefacts went up on auction at a Johannesburg based auction house. Photographic images in this collection fetched high prices. However, images that high-end bidders did not pursue with the same vigour were magic lantern slides in the collection. Why would this be?

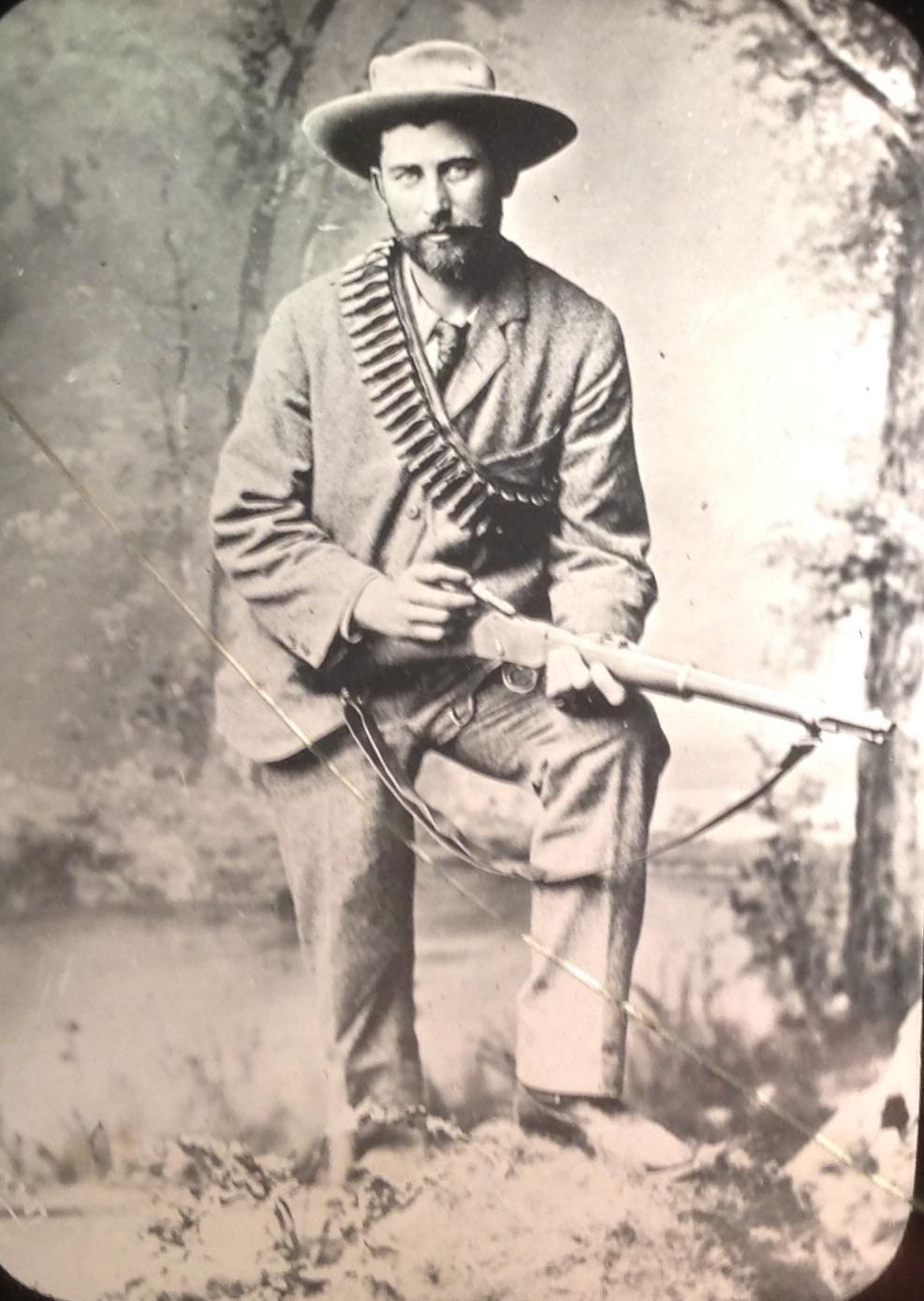

Anglo-Boer War – Posed images of Boer soldiers are less common compared to those of British soldiers.

Often ignored by collectors and researchers, or even misidentified in historical photograph collections, magic lantern slides have been described as having a less than authentic reputation? Is this a justified view?

In this article, the author briefly reflects on the history of the lantern slide as well as South African themed magic lantern slides. From the outset it needs to be stated that more research is required on the many facets of the South African lantern era.

Brief History of the magic lantern

Magic lanterns were in use long before the first photographic image, the daguerreotype, was produced during 1839.

The magic lantern was first described during 1659 by the Dutchman Christian Huygens. In a diagram attached to his notes, he showed the arrangement of a concave mirror behind the light source, a biconvex condensing lens, the slide, and a biconvex objective lens which became the standard optical system for magic lanterns (Permutt, 1986).

A friend of Huygens, Richard Reeves, introduced the magic lantern to England the following year. Reeves described this unique device as “the lanthorn that shows tricks” (Permut, 1986).

But why was the projected image referred to as a magic lantern slide? The projectors of old, the magic lantern, were so called due to a small image mounted between two glass pieces and when projected created a larger image – Magic! The name stuck – Magic lantern and therefore the magic lantern slide.

The earlier magic lanterns used sunlight or candlelight for illumination. Oil burners gradually replaced candles. The level of illumination was further improved by placing a concave mirror behind the oil burner to reflect and concentrate the light on to the lenses. The introduction of the Argand pot lamp (oil lamp named after a French physicist) during the late 1770s used a circular wick to supply oxygen to the centre of the flame, a chimney to provide extra upwards draught and a pre-heated thick oil for fuel which in turn provided for a far better illumination compared to any preceding lantern types.

Before magic lanterns became electrified, kerosene was widely used for illumination.

Some magic lanterns were elaborately made. Sizes varied. Some were large units which were mainly used at public exhibitions (with up to three lenses), whilst smaller units were produced for children.

The magic lantern remained in use until the mid-20th century, whereafter it was superseded by a more compact version that could hold multiple 35mm photographic slides, namely the contemporary slide projector.

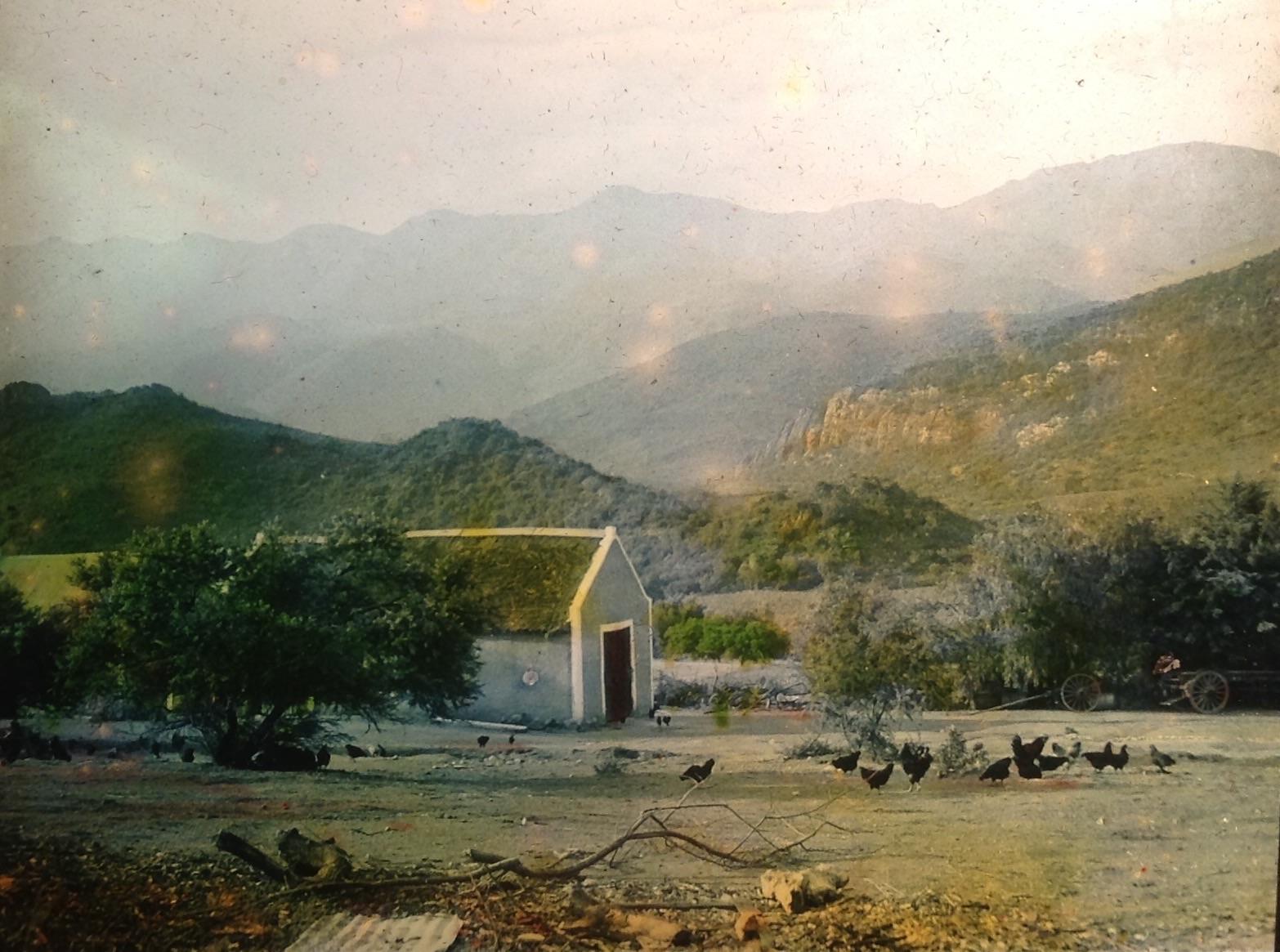

Hand coloured photographs of farm scenes somewhere in the Cape Province

The Magic Lantern slide

The magic lantern slide (towerlantern skyfie in the Afrikaans language) either consisted of a photograph, colored drawing or a sketch reproduced from newspaper publications.

In order to project the fragile finished image, the coated side was covered with a second, same-sized piece of glass (usually 8.2 x 8.2cm), with their edges taped together with black paper tape. In some instances, images were placed underneath cut-out paper masks.

Slides are frequently found in sets covering a single subject and are housed in stout, wooden lidded boxes, grooved within to accept each transparency separately. Magic lantern slides are often confused with glass negatives. There are however several important differences between the magic lantern slide and a glass negative. The most obvious being that the lantern slide is a positive and not a negative image. Also, glass negatives varied in sizes whereas the lantern slides were uniform in size.

Originally an image painted on glass, a lantern slide only became photographic during the 1850s with the use of an albumen, or later collodion coating on one side. Either kind of coating contained light-sensitive silver salts, which, after being developed, produced a positive transparency. Most of the early hand-made slides were mounted in wooden frames with a round or square opening for the picture.

Unlike wet plate photography, dry plates could be prepared in advance and did not require copious chemicals and equipment, or immediate and on-site development in a dark room (photographers had used cumbersome portable tents for this purpose when working in the field). It was the dry plate method that allowed photographic processing to become commercialised in the 1880s.

Franshoek (Circa 1910). Image may have been captured by DG Houliston. Slide has handwritten title: “French Hoek from pass (telephoto)”

Commercial production of magic lanterns slides quickly became big business. In America, the Philadelphia based Langenheim brothers engaged in full-time production of lantern slides as early as the 1860s. The slides were referred to as stereopticon slides. The similarity of this name with that of the stereograph has resulted in confusing stereopticon slides with the twin opaque prints of a stereograph.

From around 1907 onwards, natural colour lantern slides were also made in quantity. A short description of the image may also have been applied on the slide.

Lantern slide projection enjoyed a long life as popular entertainment, both at home and at larger gatherings where public illustrated lectures, often edifying in nature, were immensely popular. Magic lanterns were the showman’s affair, whilst the slides were very much the concern of audiences on whose approval the showman’s fortunes depended. These showmen were also referred to as illuminators.

Lantern slides reached their greatest popularity during the 1900s. Sets of slides for both home and professional use were sold covering almost every conceivable field of interest varying from architecture, agriculture, scenic, war, railways, missionary, ethnographical, medical to zoology or simply just faraway places.

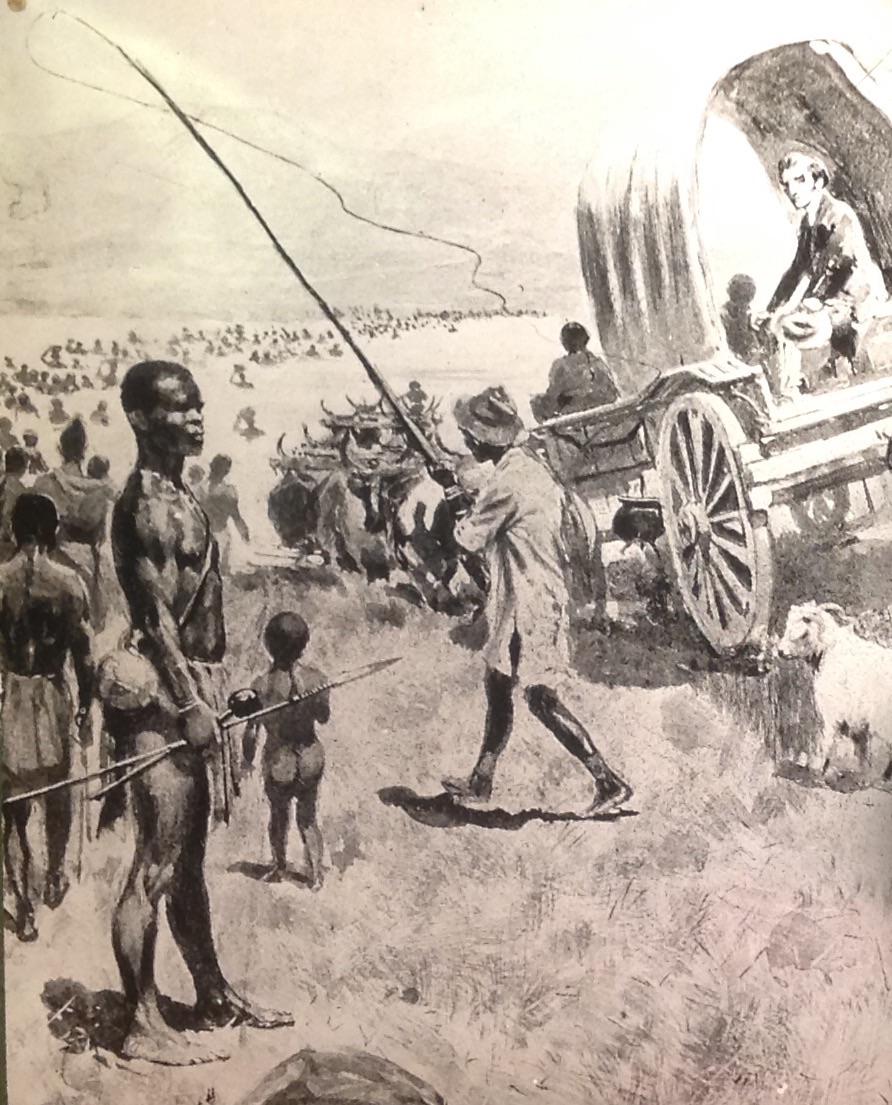

Sketch depicting a single ox-wagon crossing a river with a large number of Zulus leading the way

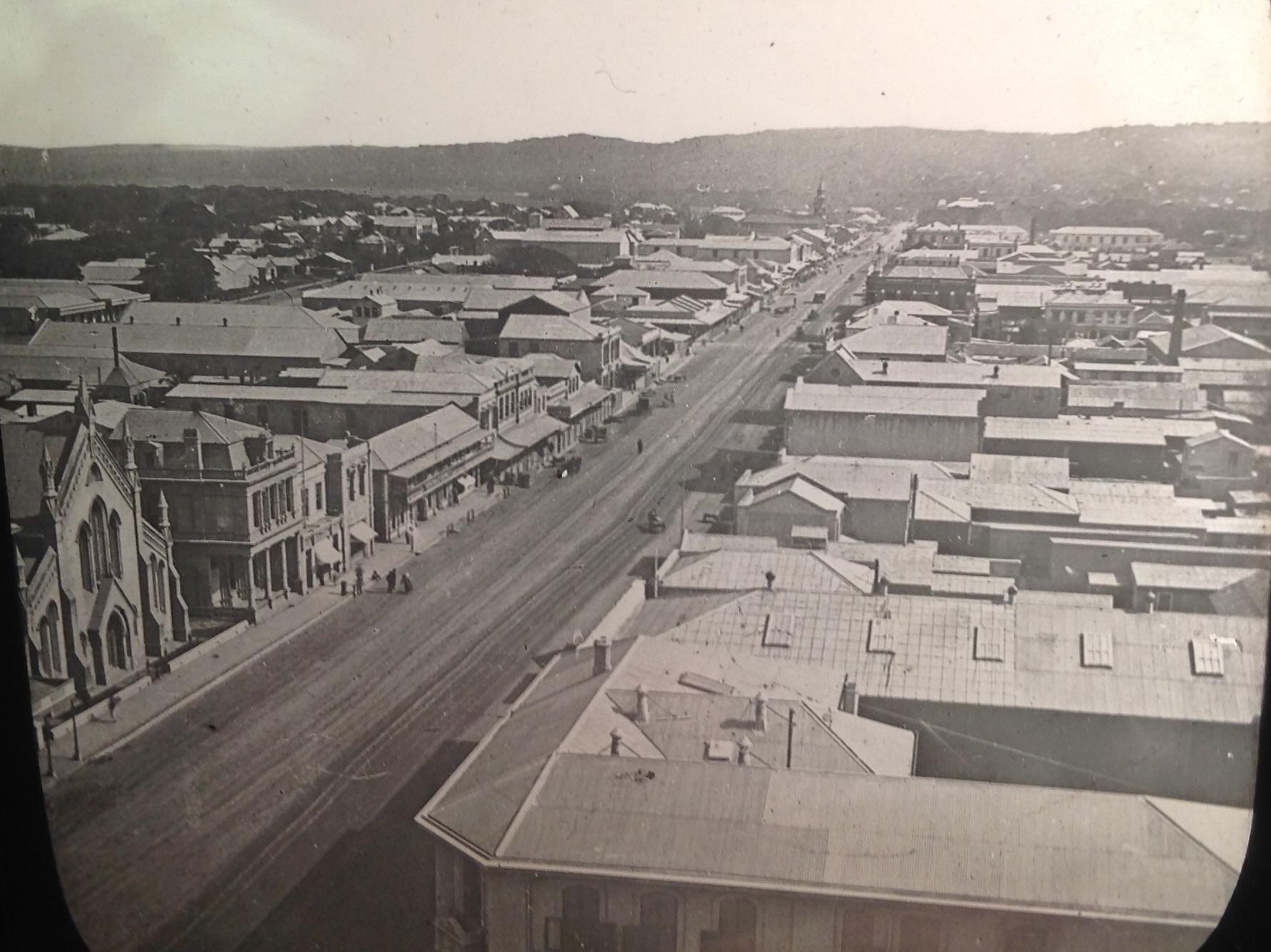

Topographical slide depicting Durban West street from the “Transvaal in peace” series numbered 49 (Circa 1908)

Old NG Moeder Kerk Swellendam

Subjects therefore range from the commercially produced narrative series to holiday photographs taken by amateurs. Slides produced by amateurs are less likely to have survived over the years in that inheriting family members would have destroyed such images in that they would not have been able to relate to the era as portrayed on the images or they would not have had the required equipment to project the images.

The types of slides varied. First attempts to produce motion on the screen were with the revolving mechanical magic lanterns slides. Movement was achieved when a little handle, which formed part of the magic lantern slide, was turned. Another format was where a second glass with black patches was slipped over the fixed glass which contained the actual painted image. This second glass piece, when manipulated by hand, then covers or uncovers the various stages of the action creating the illusion of movement. No examples of South African themed slides with the special illusionary effects as described here have been identified by the author to date. It is therefore very probable that no such slides were ever produced in South Africa.

Lantern slides however did not have the same popularity as stereoview images because of greater expense and the necessity for subdued viewing light required. As for the stereoview images, lantern slides may often be the only photograph of a subject or area that have survived.

Many lantern slides, mainly commercially produced, have survived in remarkable good condition. Most of them have received limited use and have been kept in their grooved wooden storage containers resulting in the usual abrasions, dirt, finger prints and direct contamination from a variety of sources so often seen on negatives being avoided.

Intense projection light and accompanying heat can be harmful to the life of a slide. The rule of thumb for the illuminator back then was not to expose a slide for longer than 15 seconds under these harsh conditions.

Non-commercial image of two Pretoria based children (Circa 1908)

An interesting social photograph stating “My Dutch landlady and family – Pretoria - 1901”. Names captured on the slide are H. Leibrandt, Miss & Mrs Bantjes and van Zijl

South African magic lantern slides

Little is known about the development and history of lantern projection in South Africa.

In true Victorian and Imperial fashion, lantern imagery was widely produced across the empire during the 19th century with themes varying from ethnological, missionary or wars such as the Anglo-Boer war. Foreign interest in the South African landscape and broader population would have been insatiable. This is the main reason for the bulk of South African themed magic lanterns being found in the United Kingdom, Europe and Northern America.

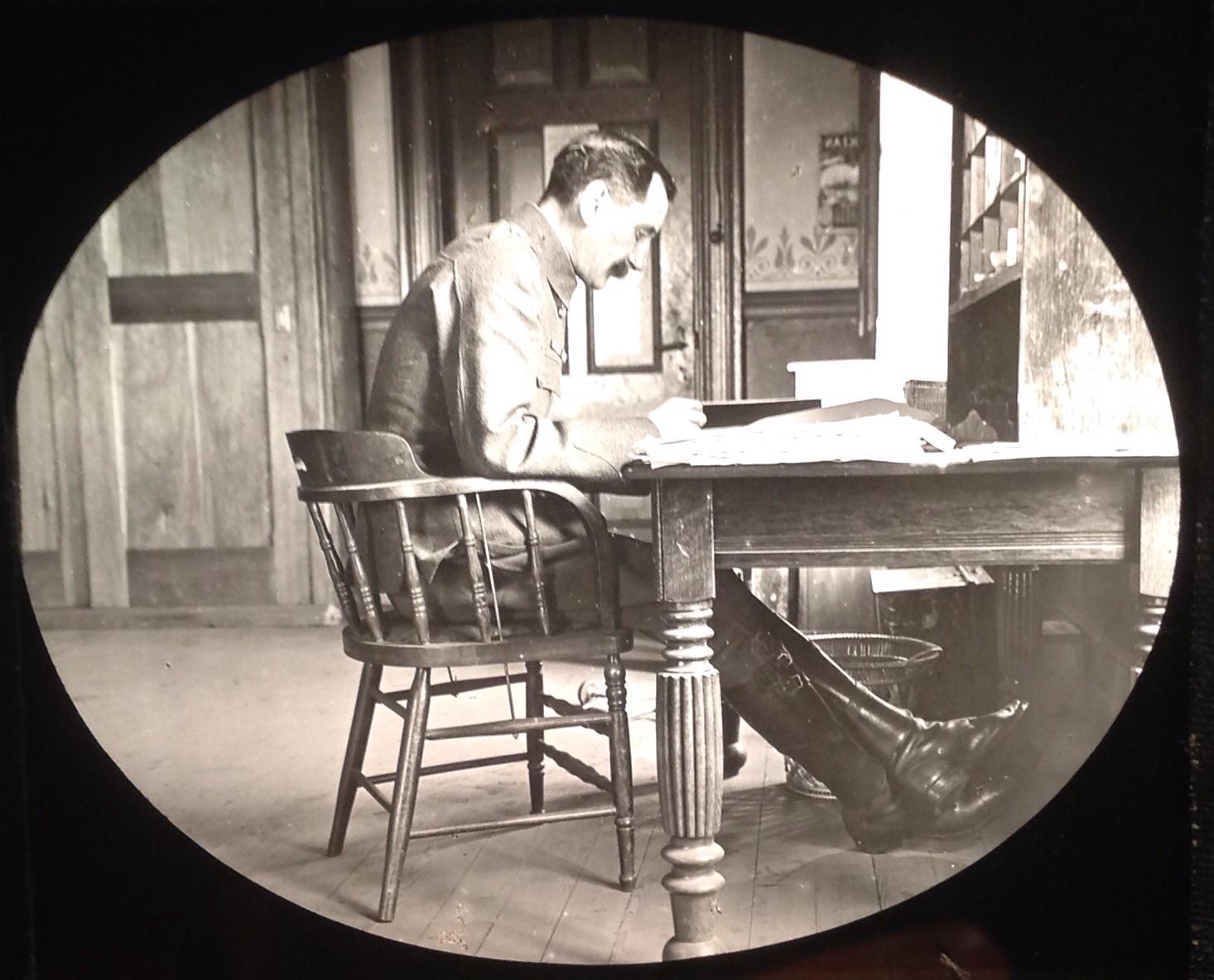

Anglo-Boer war slide titled: “F.I.D (Field Intelligence Department) Pretoria – David Henderson” Henderson was the British military Director of Intelligence.

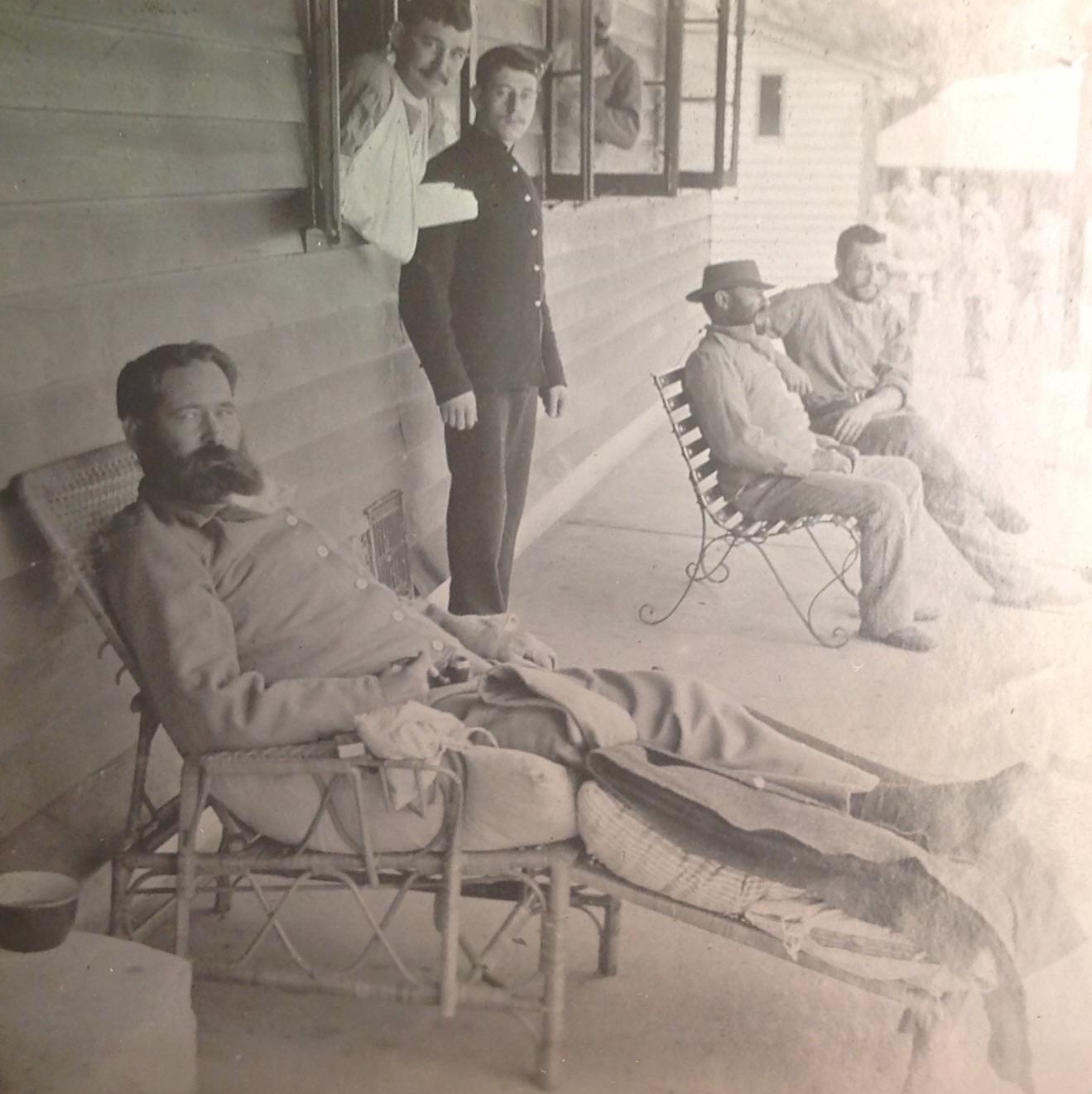

Anglo-Boer War - Military hospital showing what seems to be Boer and Brit at the same facility. The soldier seated in front clearly has his right leg amputated

Numerous educational institutions, religious organisations, asylums, and government departments would have bought, commissioned or made their own lantern slides.

Finding South African themed magic lantern slides in South Africa remains a challenge. The Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection houses less than 250 of these images. The large bulk of this magic lantern slide collection consists of missionary photographs (See article: Early Mission Photography in the Namaqualand – theheritageportal.co.za).

Bull & Denfield (1970) and Bensusan (1966), the only two publications providing a detailed overview on South African photographic history, hardly make any reference to lantern slides, illuminators etc.

The only brief reference is by Bensusan (1966) in which he states: “Late 1880s, Allcock gave a number of talks illustrated by lantern slides, mostly for charitable purposes. This evening entertainment became popular. A presentation presented in the Cape Town hall (in favour of the Children’s hospital) was attended by some 450 people” (Not captured verbatim).

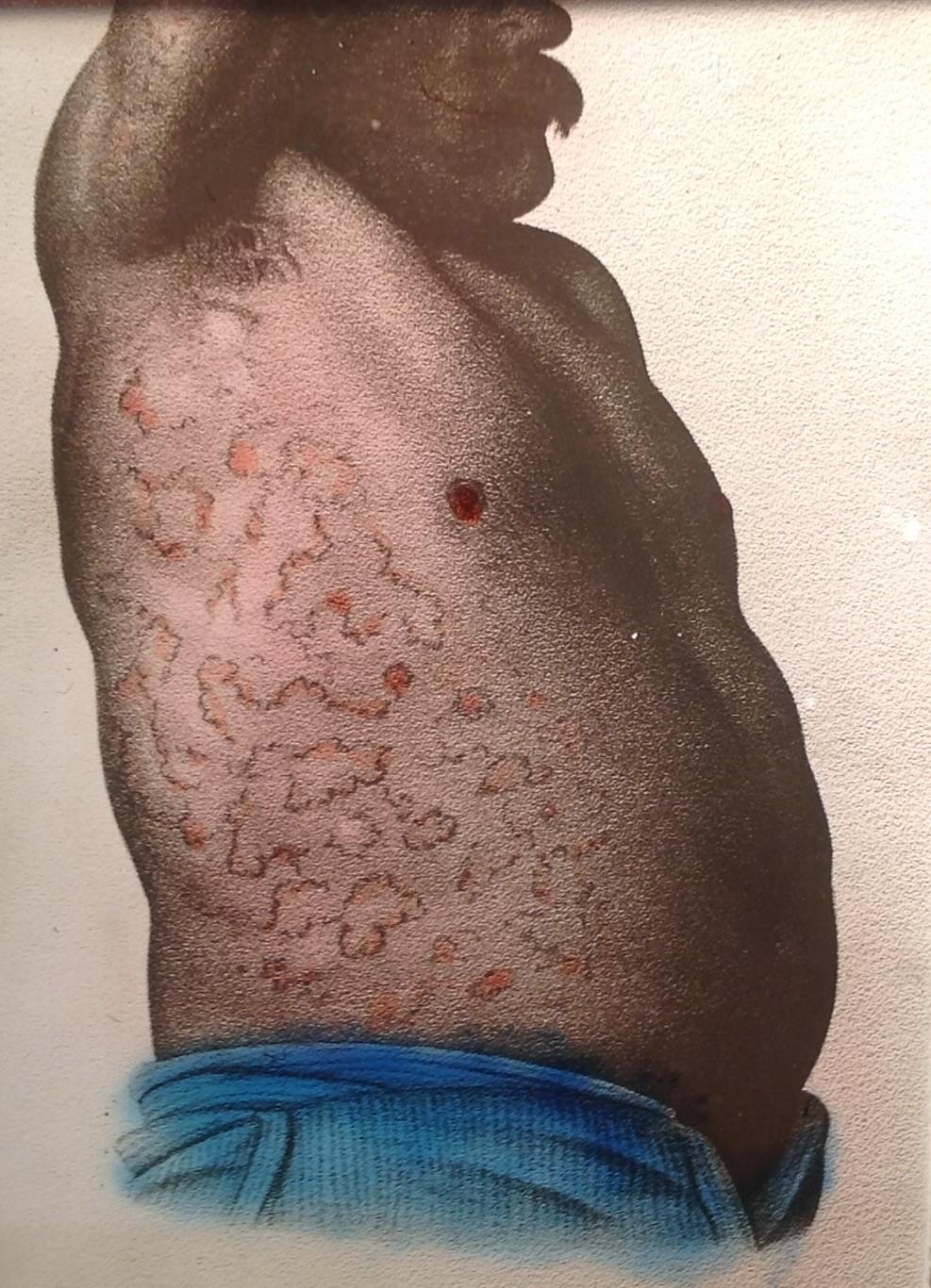

Several South African photographers would have produced lantern slides. An advertising pamphlet included with some photographic images (converted to slides), showing severe medical skin conditions, indicates that a Mr. T. Dunye was an active Johannesburg based illuminator situated at the Arcade buildings in President street (Circa 1910). On this pamphlet, he advertises that he:

- produces “artistic lantern slides”;

- produces lantern slides from black and white photographs (at £2.6) and from color photographs (at £4.0);

- produces magic lantern slides taken from “living human beings” at £3.3 per day;

- Supplying all necessary machinery for projecting lantern slides in hall at £5.5 a night

A medical image depicting an image of a male with some sort of skin condition. This image was distributed by Dunye, a Johannesburg based illuminator

Another South Africa photographer was Pretoria based WH Anson. It has been recorded that during 1909, Anson offered the agricultural department magic lantern slides for lecturing purposes.

Archival records indicate that he also produced multiple lantern slides for a JJ Nicholson and that he also quoted the company N & H Bricks for producing lantern slides.

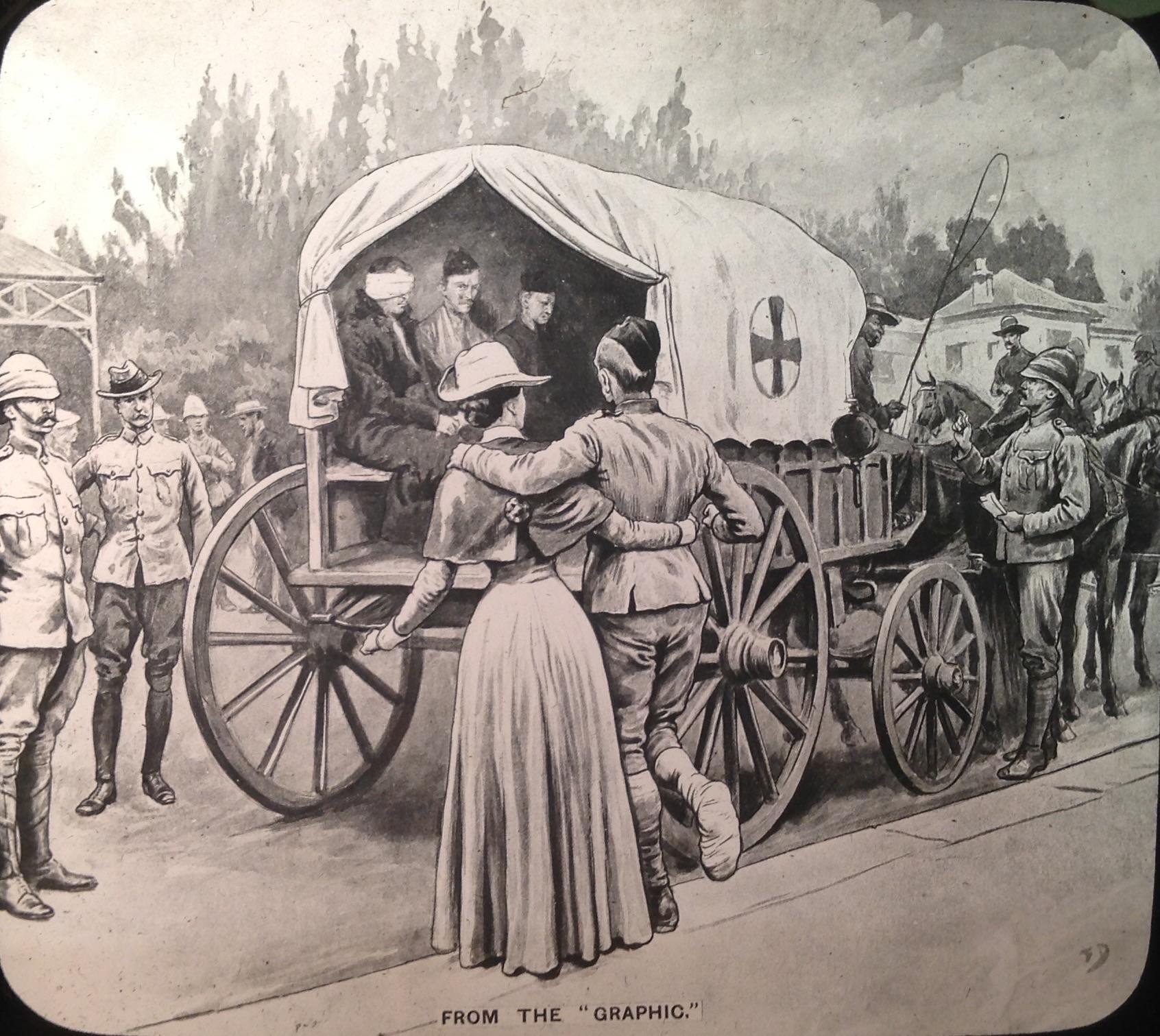

There was an enormous public interest in any images relating to conflict. The Anglo-Boer war was one such topic that was a popular entertainment theme. This is confirmed by the quantity of war news and images produced. The relation between the lantern shows and paper based illustrated news were closely aligned in that the slide images were sourced from British illustrated news publications such as The Sphere and The Graphic and integrated into these lantern performances.

Anglo-Boer war sketch originating from “The Graphic” depicting a British ambulance wagon

Not all South African themed magic lantern slides were produced in South Africa.

For example, some Anglo-Boer war slide sets were manufactured by British based W. Butcher & Sons, who traded under the name Primus. This company produced slide sets in a “Lecture Series”. Primus slides were sold in chapters, consisting of eight slides. There are four chapters to the “Our South African Heroes” series, entitled “Perils Past”, “On to Victory”, “An Invisible Enemy”, and “Men in Khaki”. Each of these chapters comes with a lecture script. The projected images in the original performance would have had the lanternist reading out the script narrating the action of the slides. The lectures would in all probability have been triumphant, patriotic and at times melodramatic in nature. War events of this nature, no doubt, would therefore have been sensationalised during these shows.

Whilst the author is of the view that South African themed magic lantern slides would mainly be found abroad, it was a pleasant surprise to find a vast South African themed magic lantern slide collection at the Johannesburg based Transnet Heritage Library Photo Collection. This slide collection, amongst many other artefacts, has been diligently catalogued and scanned by volunteers under the guidance of Johannes Haarhoff (Volunteer Project Leader) and Yolanda Meyer (Information Specialist). These more than 1300 historically important images can be viewed on www.drisa.co.za (Select “LS” for lantern slides).

Significant about this slide collection are the unique wooden boxes in which these slides are stored. These boxes each have a thick leather carrying strap. As part of the South African Railway (SAR) publicity campaigns, these boxes were then sent to destinations such as USA (New York & Pennsylvania amongst other) and multiple other European cities. Whilst South African embassies may have been the primary recipients of these boxes, the probability is not excluded that they were also destined to foreign travel agents, photographic distributors and so on. These boxes were returned to South Africa from where they would then be redistributed to the next destination. The probability exists that some of these boxes containing the magic lantern slides never made it back home to South Africa.

The existence of such a large magic lantern collection suggests that the South African Railway Publicity and Travel department would have manufactured these slides in bulk. Interestingly enough, a 1911 SAR annual report refers to the “energetic advertising” by the SAR publicity and travel team in producing these magic lantern slides. This confirms that there was a high production of lantern slides for distribution worldwide. There is no doubt that multiple duplicate images would have been produced in the process. This raises the question – how many slides were produced by this department and where are the remainder of these images today?

Komnick (2019), administrator at the South African Parliament’s Artwork Collection based in Cape Town, confirmed that this collection also houses some 238 South African themed magic lantern slides. Significant about this collection (not seen by the author) is that it contains a number of images from the 1st Anglo-Boer war (1880-1881). Should these images not have been reproduced from photographs for slide shows during the 1900s, then this would be the earliest produced South African themed magic lantern imagery identified in South Africa to date.

Zuid-Afrika Huis, based in Amsterdam, also houses a collection of South African themed magic lantern slides which happens to have been discovered in the rafters of their building. To date, it could not be determined beyond reasonable doubt as to where these images originate from. Were they produced by the SAR team or by other South African based or even foreign photographers? Some of the slides have Afrikaans descriptions on them which confirms that they were produced in South Africa.

It is very probable that there are many more South African themed magic lantern slides lying dormant worldwide or even in South African archives and museums, in their wooden boxes, waiting to be uncovered.

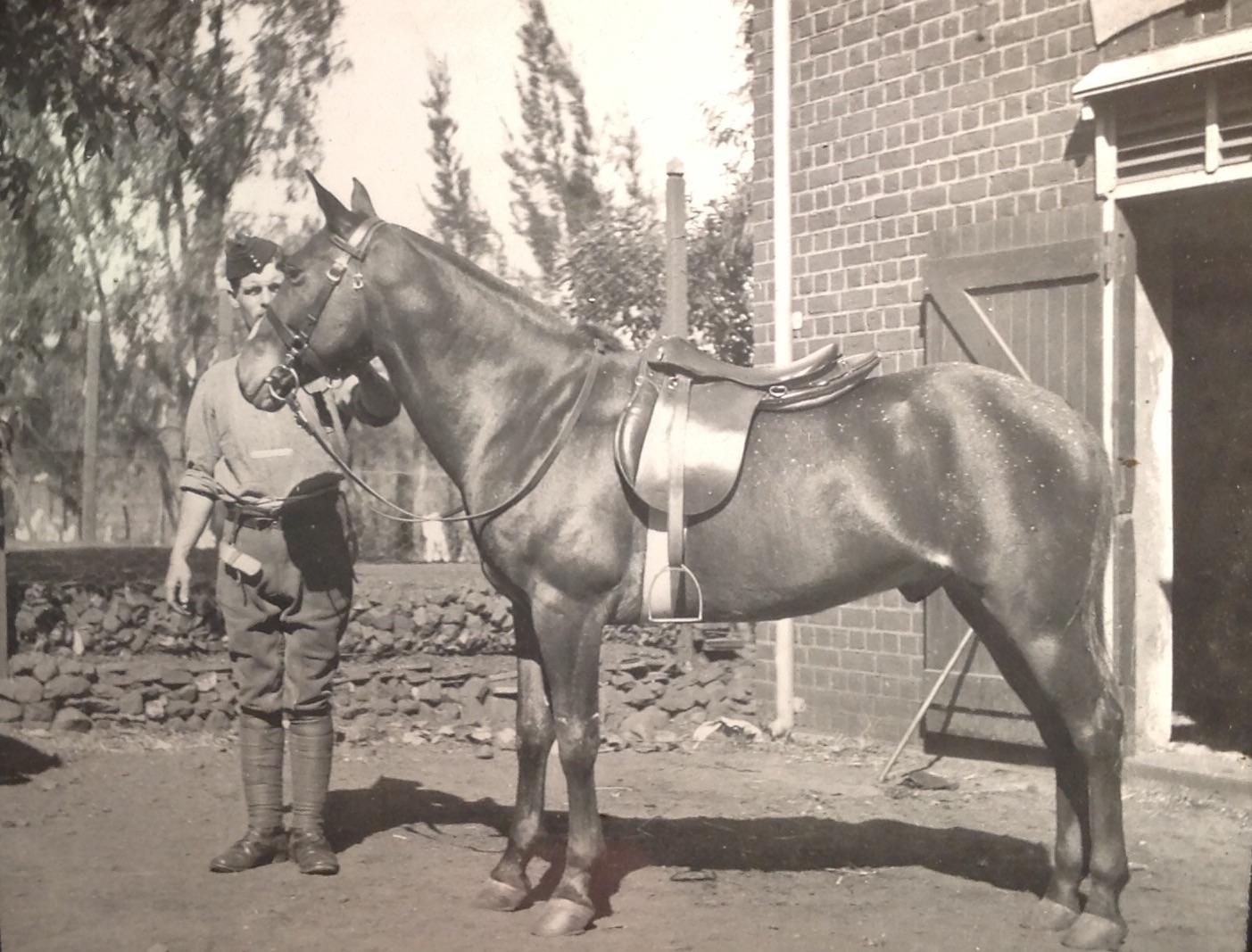

Photographic slide of British soldier Peters with his horse at the Pretoria Military Head Courters (Circa 1902)

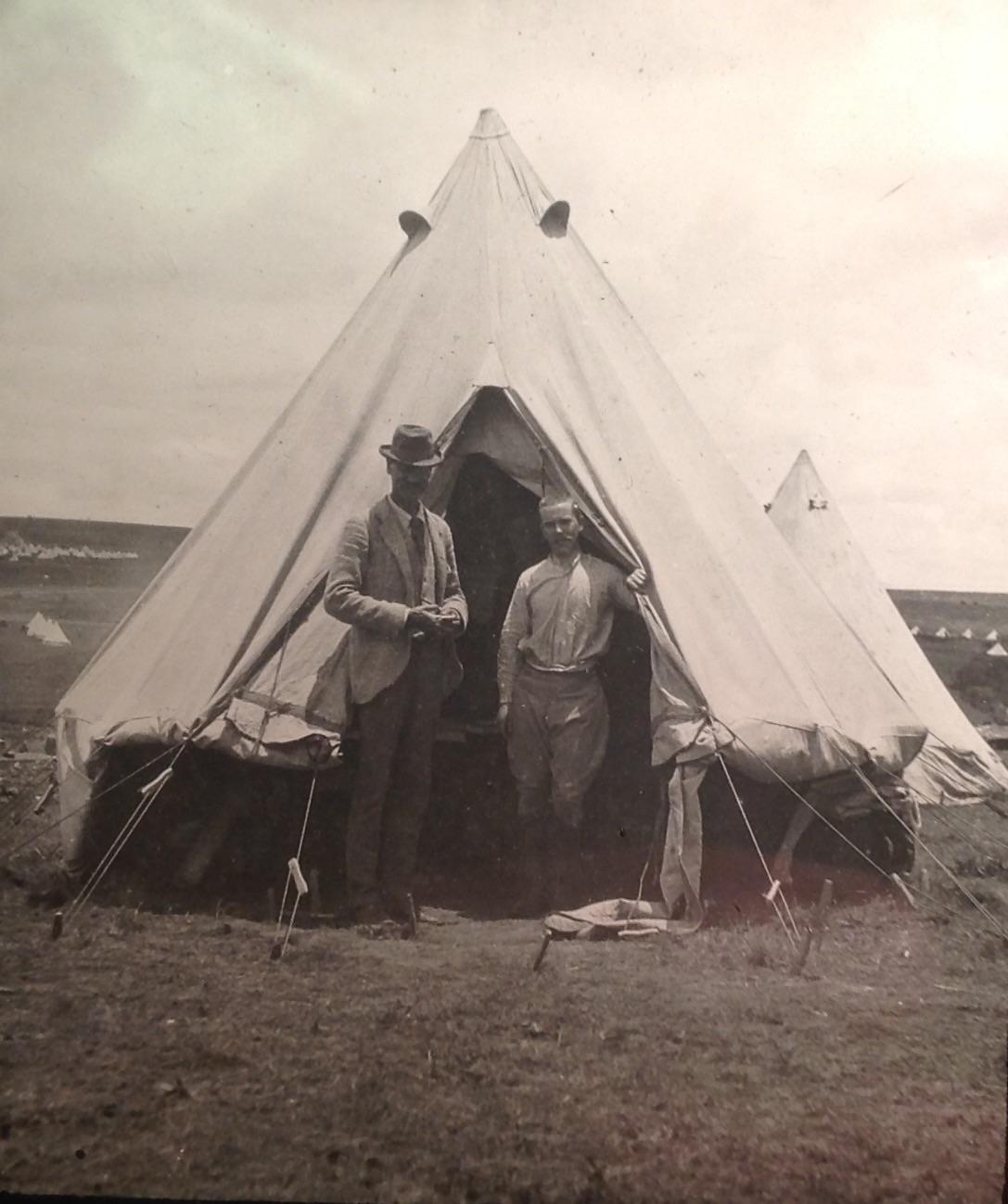

Anglo-Boer War – F.I.D. (Field Intelligence Department) camp in Frere, Natal. One of the two men is Tom McFarlane

The magic lantern slide collector

Magic lantern slide collectors concentrate on slides of subjects that interest them personally, yet any outstanding example or tempting bargains would remain hard to resist for the die-hard collector.

The Magic Lantern Society of Great Britain has identified some 22 different collector categories of different format lantern slides. South African production of magic lantern slides would not nearly have been as sophisticated compared to the British/European markets, resulting in a significant lower number of formats that would have been produced in South Africa.

Although the most common problems for magic lantern slides are deteriorating tape or cracked glass, maintainance and storage of the magic lantern slides is easier, compared to the glass negative for example, in that storage in their original containers, combined with the covering and binding, have protected the images from serious physical damage.

Conclusion

The magic lantern slide has played a pivotal role in the history of the projected image.

The author concurs with Stobbe’s (2019) observation: “Due to their less ‘authentic’ reputation, these types of slides have long been overlooked as an interesting source of information”. South African themed magic lantern slides have become a significant relevant source of visually valid information indeed.

The title of this article suggests that lantern slide imagery is latent or dormant. Due to the image being difficult to display (without being held to light or projection), it does not provide for immediacy resulting in this format having been ignored by collectors and researchers worldwide.

Multiple research opportunities exist on the topic of South African magic lantern slides.

Back to the auction of the Anglo-Boer war magic lantern slides in Johannesburg during mid-2019. Due to a lack of interest in these images, the author acquired the slides at a very reasonable price.

Main image: Anglo-Boer War (1902) image showing train wrecked by rebels

About the author: Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources

- Baldwin, G. (1991), Looking at photographs – a guide to technical terms. J. Paul Getty museum. London

- Bensusan, A.D. (1966). Silver Images. Cape Town: Timmins.

- Bull, M. & Denfield, J. (1970). Secure the Shadow – The story of Cape photography from its beginnings to the end of 1870. Cape Town: McNally.

- Crompton, D; Henry, D. & Herbert, S. (1990). Magic Images – The art of hand-painted and photographic lantern slides. The Magic Lantern Society of Great Britain. London.

- de Waal, M.; Stobbe, J. & Deen, R. (eds.). Magic Visions: portraying and inventing South Africa with lantern slides, 1900-1920s. ZAH Series no. 2 (in prep. for 2020).

- Digital Rail Images of South Africa (DRISA). Drisa.co.za

- Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection

- Hardijzer, C.H. (2017). Early Mission Photography in the Namaqualand (theheritageportal.co.za)

- Hardijzer, C.H. (2018). Photographers active in Pretoria – First 60 years (1855 – 1915). (theheritageportal.co.za)

- Komnick, L. (2019). Email communication on South African Magic Lantern slides held at the South African Parliament Artwork Collection – November 2019

- Permut, C. (1986). Collecting photographic antiques. Patrick Stevens. Wellingborough

- van der Walt, P. (2019). Email communication on South African Magic Lantern slides - July & August 2019

- Stobbe, J. (2019). Archivist – Zuid-Afrika Huis – Amsterdam. Email communication on South African lantern slides - August 2019

- Transnet Heritage Library Photo Collection

- Unknown (extracted June 2019). The Boer war as a lantern performance (Sheffield.ac.uk)

- Unknown (Extracted August 2019). Magic Lantern. (Wikipedia.org)

- Unknown (extracted November 2019). Illumination & Commemoration – A history of the lantern slide (Seagerlanternslides.nz/lanternslide)

- Weinstein, R.A & Booth, L. (1978). Collection, use and care of historical photographs. American Association for State and Local History. Nashville.

Note: The images included in this article all form part of the Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection. The images were reproduced by photographing the original magic lantern slide which was placed on an antique wooden touch-up desk (with light reflecting on the white glass background).

Special acknowledgement is due to Johannes Haarhoff and Yolanda Meyer for hosting the author at the Transnet Heritage Library in order to view the magic lantern collection.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.