Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Although Cape Town has had a port for hundreds of years, it has never been a port city like, for example, Istanbul. It was started as a result of human necessity by the Dutch East India Company in the 17th Century as a half-way house and watering hole on the long voyage to India. However, by the fifties, the richer, mostly white population had moved away from the exfoliating atmosphere of tar and sea- winds of the docklands and made for the more salubrious suburbs with their welter of lush green lawns and stench of privilege.

The docks, the ships, the stoves, the grit, the coal heaving quickly slid beyond suburban view, too raw for the upwardly mobile and the docks soon became a place they visited on Sunday afternoons to wave Union Castle liners goodbye.

There is very little record of this part of town, which is why Billy Monk's photographs form such a vital link, not least because it is here, too, that slaves lived out chained lives and form a forgotten part of the fabric.

The docks became a place of edgy survival and even venality, a place where broken parts were recognised, where you could glimpse the salt mines of grief, depression, narcissistic injury and alienation, as seafarers from around the world searched for a loving touch. The Catacombs nightclub with its under welt of prostitutes, pick pockets and pimps symbolised this world and this is where Billy Monk found his home. A survivor who had crossed swords with apartheid by marrying a coloured woman, he worked as a sometime bouncer and a nightclub photographer and soon became a well-recognised part of the dockerati.

Outside the Catacombs, 14 October 1967 (Billy Monk Collection)

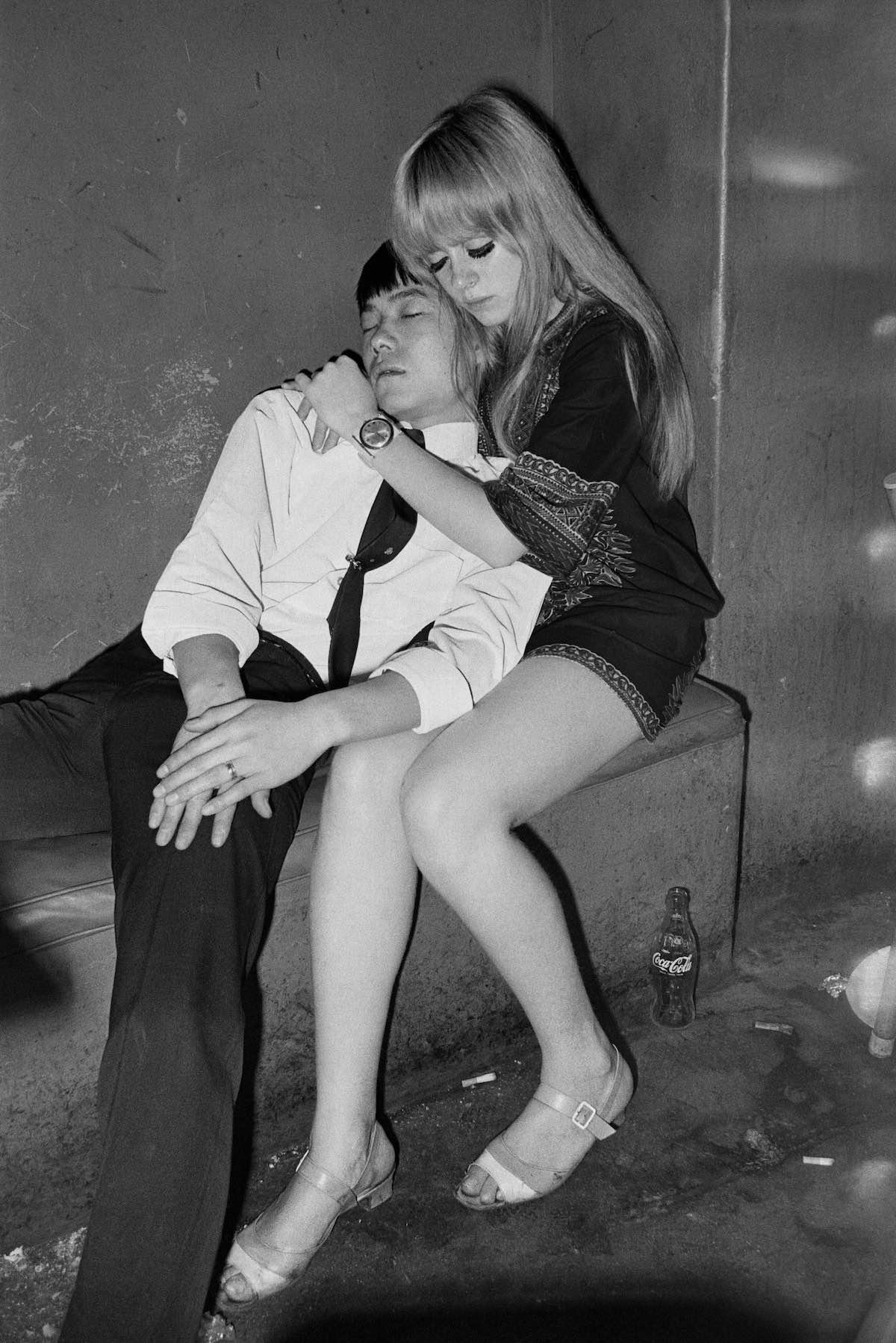

The Catacombs, 9 February 1968 (Billy Monk Collection)

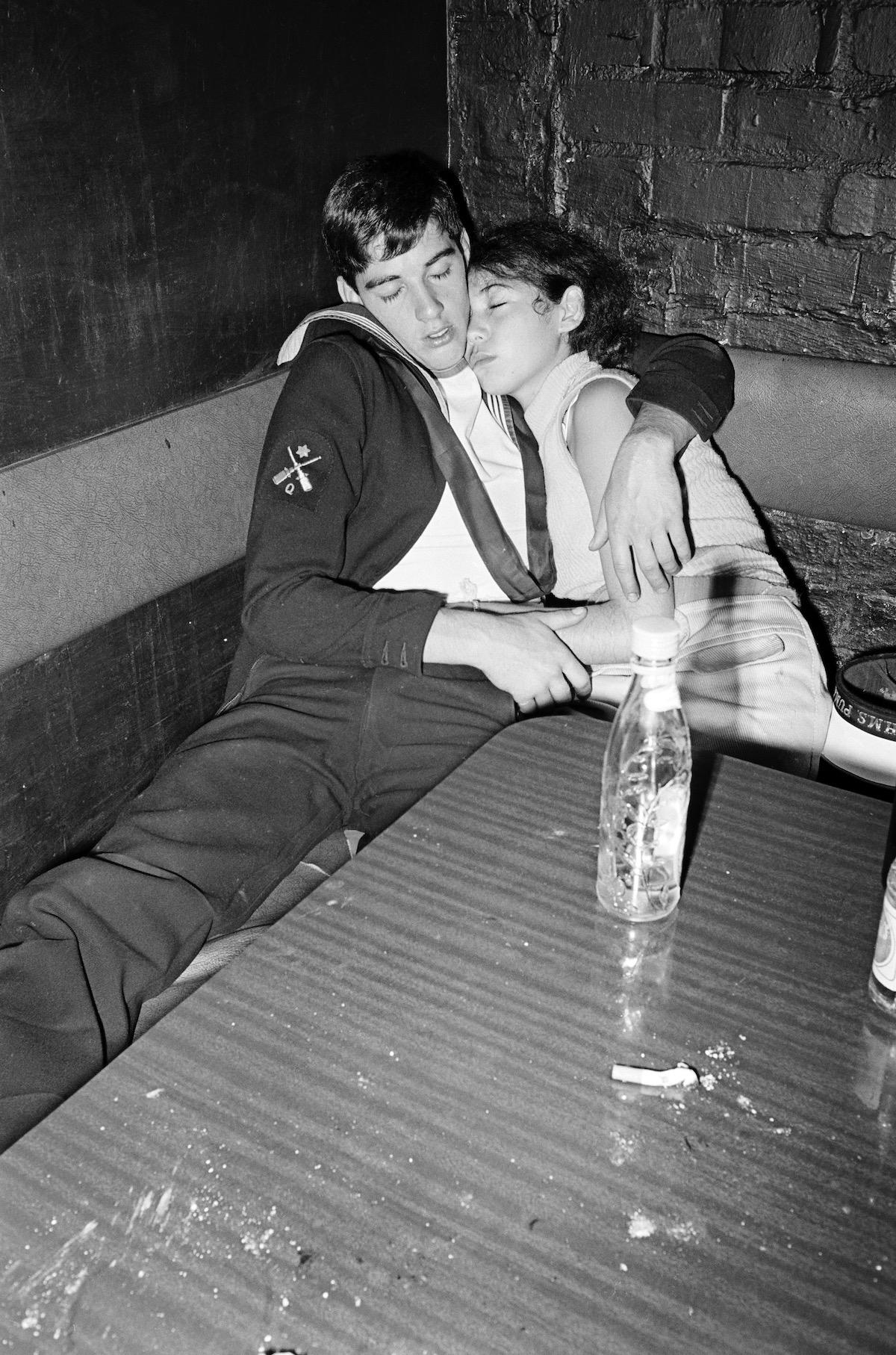

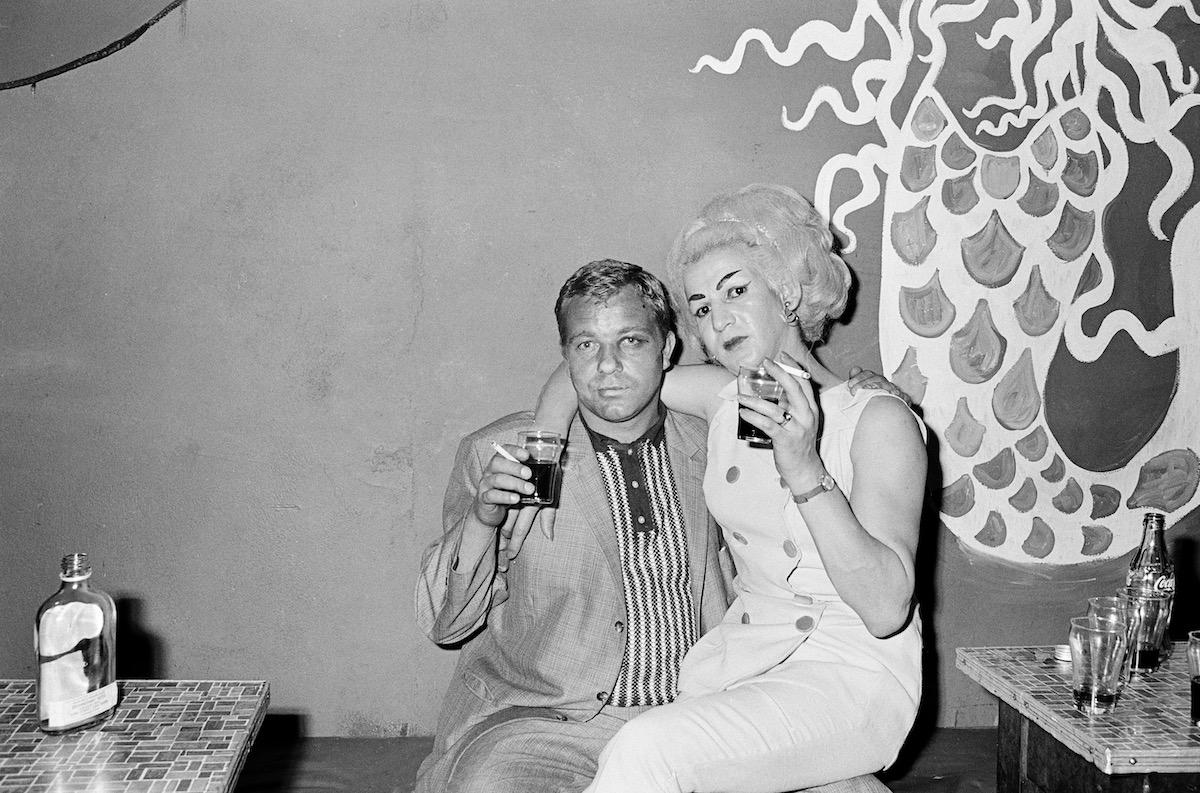

The Catacombs, 28 February 1967 (Billy Monk Collection)

Billy himself was a survivor of the mean streets of Cape Town where poverty denied him access to luxurious pastimes and where apartheid’s colour bar made going out with his wife a furtive undertaking. However, The Catacombs with its innovative coffin shaped tables was like a ‘third place’ in those agonising times, where people of every colour and ethnicity could meet. Many of the trawler men and sailors wanted to meet white girls and avoided the local brothels. Many coloured and black musicians barred from playing in hotels and clubs, found a home at The Catacombs nightclub with its heart and inexhaustible supply of Brandy and Coke which helped to highlight the spirits; a girl takes off her top and dances on the table and a guy flips her stockings. On the back wall a porn movie flickers. The effect was quite magnificent, if you had a taste for the authentic. A black and white Rorschach blotch gone mad, there was little that could complete with this interracial vaudeville of been-around-the-block outies, schizophrenics, drunks, prostitute, jazz musicians, sojourning seamen and drag artists.

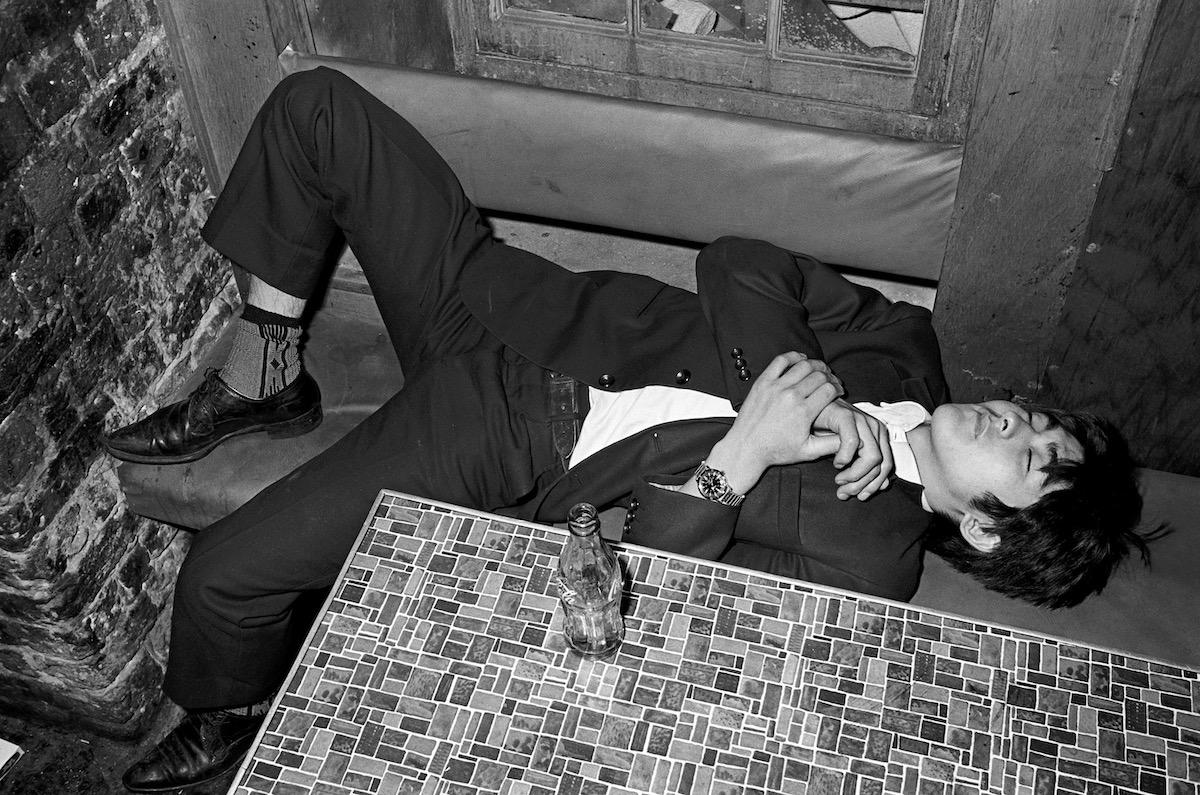

The Catacombs, 3 November 1967 (Billy Monk Collection)

The Catacombs, 3 April 1969 (Billy Monk Collection)

Over the years there have been hundreds of nightclub photographs taken, but these images really shoot the lights out.

They have a peekaboo quality, dangerously voyeuristic and transgressive. Looking at them feels like you’ve opened a secret pantry drawer. Little was known of this vibrant dock life that gave succour to the town, which is why Billy Monk and his pictures stop such a valuable gap in the tattered history of the Cape Town docks.

The Catacombs, 3 April 1969 (Billy Monk Collection)

Why did these pictures make such an impact?

Everyone when asked says, “Billy was one of them, they were not shy in front of him.” But there is more to it, they did perform in front of him, they did let the camera into their lives, but many of the images have a superfluous brutality. Perhaps Billy despised his life under apartheid and was a man full of anger, “I’ll show them how the other half lives, how sailors and trawler men, are forced to exist.” Behind many of these pictures is howl of despair for the circumstances in which he found himself and it is that primal scream that gives them gravitas.

Although he was known for his sunny smile, just the way he carried himself, with balled up fists and loose hanging arms, it was as if his body carried a secret, revealed a more complex, even sinister interior. Although there was something of the simpleton in his face, (in some pictures it looks like a large inflatable dingy) it was the fractures, the ambiguities and contradictions, on which he focused his interpretive efforts.

A woman, now in her eighties, who had been snapped by Billy says, “I tore the picture up. It revealed too much.”

The women, many of whom were prostitutes, are jellied relics with industrial strength make up and elaborate hairdos, few look desirable. With their patent leather shoes, these women are still ‘in the game’ and you can smell heartache on their breath. Not even the sweat of Bridget Bardot could bring back their youth.

The Catacombs, 13 October 1967 (Billy Monk Collection)

In a system of primate domination, Billy should have flamed, but his neural cortex was wired to transgression and his end was a firey bridge. He was shot in a fight. But behind the facades, his fate was rubber stamped, sealed with blood red wax. However hard he tried to escape this life it was limned into his neural cells, fervent with passion that slowly slid into transgression.

Billy Monk was always a loaded gun.

While Monk is now gone, his pictures live on - saved by his friend Paul Gordon and then Jac de Villiers (with David Goldblatt’s golden endorsement) and made known to the public through writer Lin Sampson in the early Eighties.

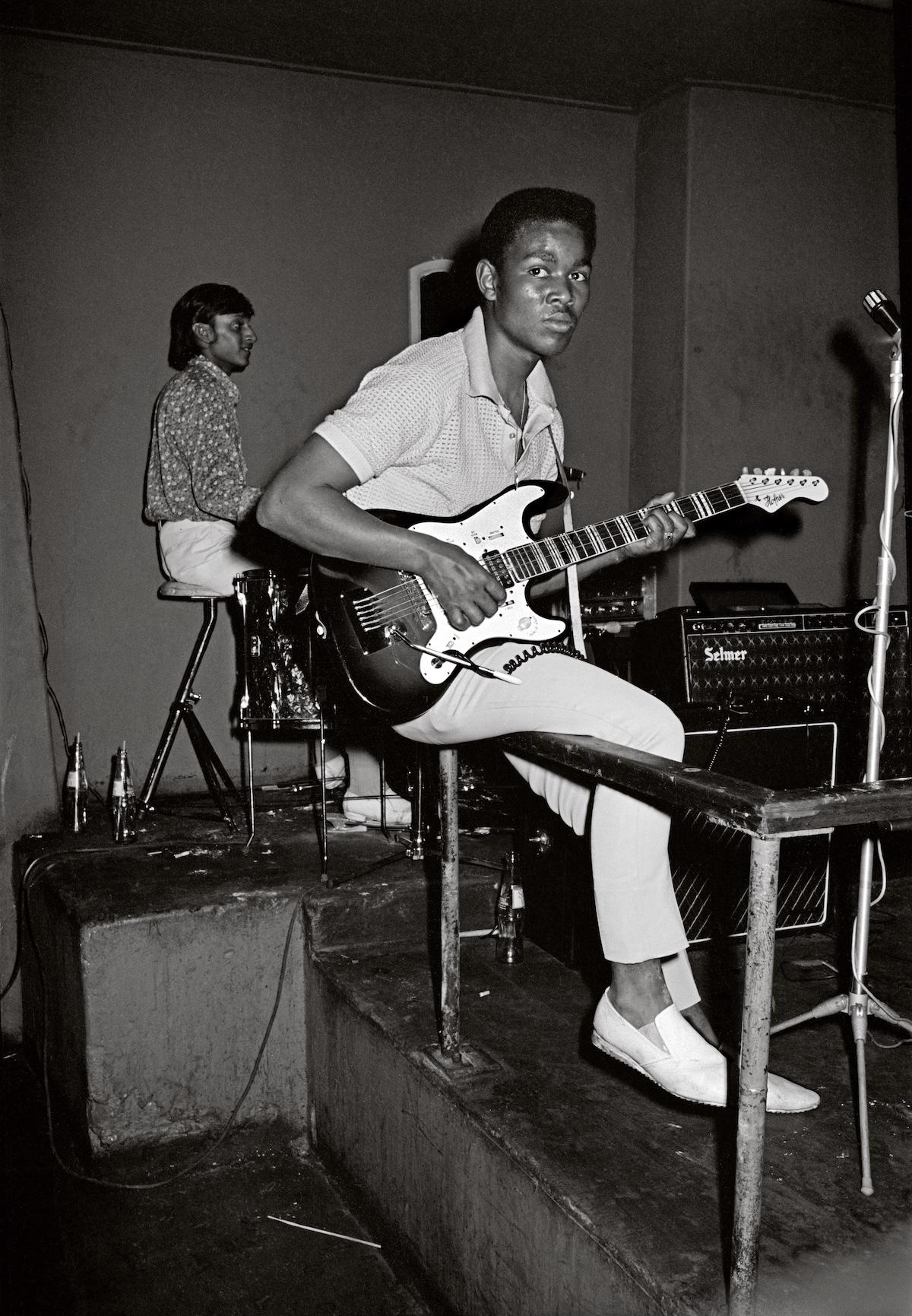

The Spurs, October 1967 (Billy Monk Collection)

The custodianship is now changing hands to Craig Cameron-Mackintosh under the Billy Monk Collection, whose focus is to safeguard and showcase this rich archive and tell Monk’s story to the world.

Main image: The Spurs, 6 February 1968 (Billy Monk Collection)

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.