During Andrew Mokete Mlangeni’s political career he sometimes had to change his name to Percy, or Mokete Mokoena. On Robben Island he got another identity as Prisoner 6447/64. But in democratic South Africa he is honoured as Om (oom) Andrew Mlangeni, the people’s person, the prestigious ‘backroom boy’. And this is how he will be remembered since he is really a people’s person, a beloved Dube resident who liked to play golf for recreation. In his biography, Kgalema Motlanthe describes Mlangeni’s life as: ‘lesson-laden, politically-charged’, while Sello Mosheo Rasethaba says he is a ‘MFD (multifunctional device)’. Yet Andrew Mlangeni preferred the title of his biography to be: ‘The Backroom Boy’.

The biography by Mandla Mathebula bears testimony to these statements. It was published by the Wits University Press. The launch was at a glittering affair at Melrose Arch on 11 May 2017. The evening drew the support of many - family, veterans, politicians, fans and book lovers. Mathebula and Patrick Baloyi (researcher) also graced the evening with their presence, together with two professionals also involved as history advisor and editor/project manager. It is an easy and pleasant read (215 pages), full of information which reveals why Motlanthe and Rasethaba wrote these introductory praises – and why the many names.

Percy Mokoena was the name Andrew got when he became one of the first six people who went to Communist China in 1962 for a year’s training in the secrets of guerrilla warfare. When Percy Mokoena returned home he was Andrew Mlangeni again, but soon he had to take over from Joe Modise in recruiting volunteers and transporting them to go for military training in Africa. For this he had to pose as Rev. Mokete Mokoena. In 1964 he was sentenced as one of the group of the Rivonia Trial and got the mentioned prisoner’s number and cell next to Nelson Mandela on Robben Island.

Mlangeni studied while in prison like many other political prisoners and when he was released after 26 years he had a degree and postgraduate qualification in Political Science. He returned to his home in Dube, Soweto, which the Mlangeni family moved into after he purchased it in 1954.

We also know 1954 marked the beginning of Dube as a township created by the Johannesburg City Council for the ‘more middle class urbanised blacks’ (and Andrew immediately formed an ANC branch in the area). Furthermore we also know that according to law then owners only purchased the improvements (house) on the stand. Title deeds for the entire property (including the land) only became available in the late 1980’s.

Although Mlangeni has been a resident of Soweto for more than 70 years, his roots are in the Free State where he was born on 6 June 1925 on a farm in the Bethlehem district as one of a twin (a sister) and grew up as a real Mosotho farm kid. When they moved to the Bethlehem town’s location after his father’s death (Mlangeni was ten at the time), he got exposure to new experiences like attending school. As a caddy at the golf course he met Bobby Locke, the then South African and world golf champion - now we know where Mlangeni’s interest and sound foundation in this game comes from.

In the 1940’s he moved to Johannesburg and stayed with an older brother Sekile in Pimville where he attended school. Afterwards he attended the St Peters Secondary School in Rosettenville where he passed the Junior Certificate (Grade 10) in 1946. One of his teachers was none other than Oliver Tambo. While there he joined the Communist Party (CPSA) and rubbed shoulders with the likes of Ruth First – for him the beginning of a remarkable political journey.

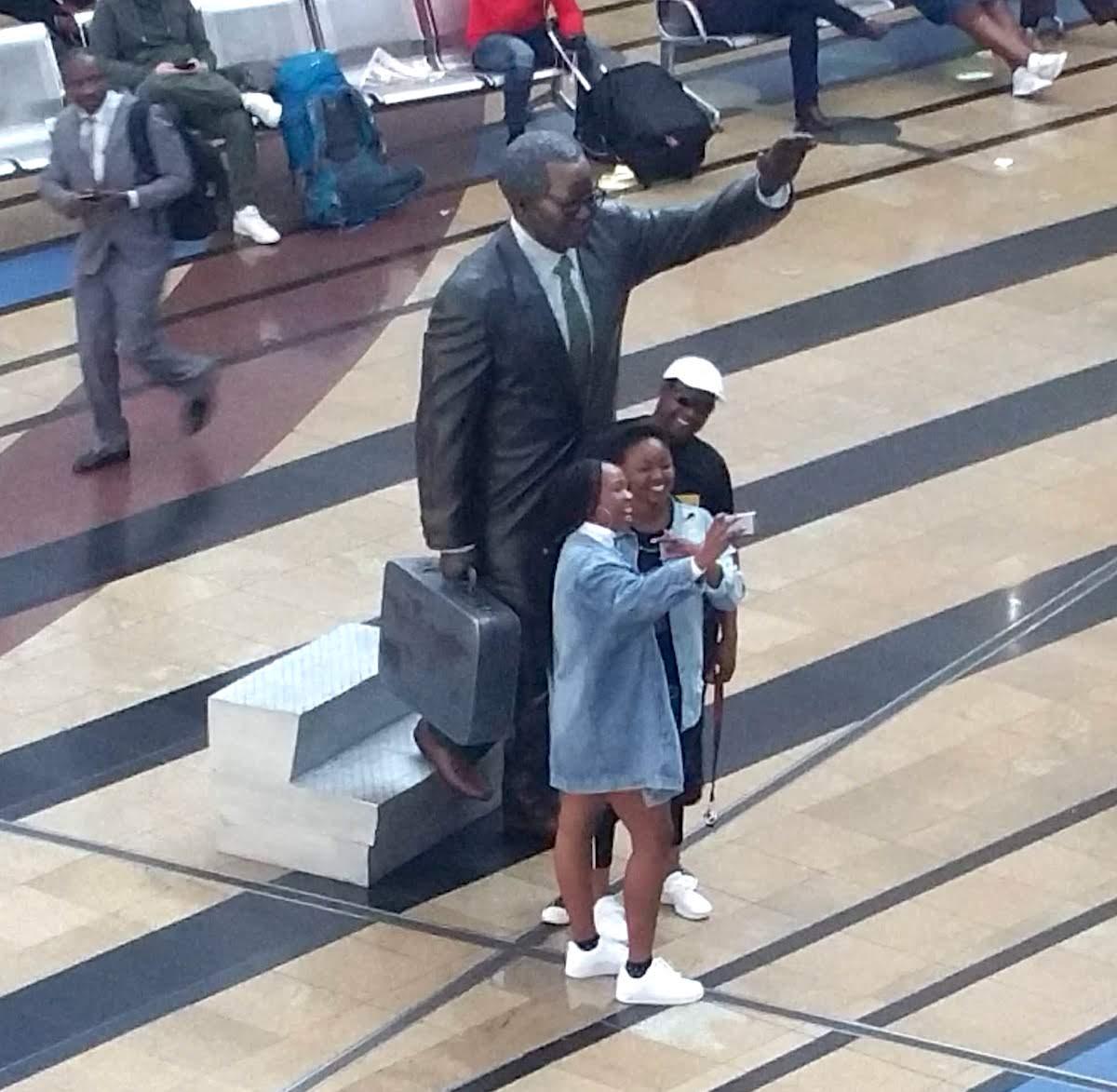

OR Tambo Statue at OR Tambo Airport (The Heritage Portal)

His first own accommodation was in what is referred to as a ‘shelter’ in Orlando West shelters (Shanty town?). His mother also had a shelter there with some of Andrew’s younger siblings and she eventually got a house. This house was probably one of the 15 000 houses built from the loan negotiated in 1956 by Oppenheimer from the mining houses to accommodate the residents of Shanty town. His mother assisted him to get an identity document (pass book?) in 1947 and told the official that he was born in Prospect location to avoid influx control measures - which were already in practice at the time – to send him back to the Free State. (In South African History Online it is claimed that he was born in Prospect and we now know why). After finishing school Andrew held a few jobs which gave him experience and skills which he could use for his political work.

The Oppenheimer Tower commemorates the Mining House loan facilitated by Ernest Oppenheimer (The Heritage Portal)

He married June Ledwaba, a young lady he first saw where she worked as a shop assistant in Orlando East. They stayed in the shelter until they moved to Dube with their children. June was his love and pillar of strength, keeping the home and family together during his absence for political activities and imprisonment. At the celebration of their 50th wedding anniversary in 2000 he said that even if they lived another 100 years, they would still passionately love each other. Regrettably she passed away in 2001, suffering from cancer.

June also spent some time in the Women’s Prison at the Old Fort with the likes of Winnie Mandela and Albertina Sisulu after a pass book march in 1957. Her life was surely not easy since we know how the police harassed the wives and families of political prisoners, while she also had to keep the home and children intact.

Women's Gaol (The Heritage Portal)

The couple’s two sons were involved in the youth revolution of 1976 and eventually went into exile to join MK and were therefore absent when Andrew was released from prison in the late 1980’s. June, the daughters and grandchildren and the Dube community, however, were there to welcome him back. A special memory he treasures is his first cup of coffee served by his own daughter Sylvia.

A rally was held at Soccer City on 29 October 1989 to welcome back political prisoners e.g. Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki and Andrew Mlangeni. When Andrew saw the cheering crowd of more than 70 thousand people, he realised there was no stopping the freedom train and from what we now know he was right. This celebration was followed by a trip into African countries for the newly released and in Tanzania Andrew was given a MK uniform by MK chief-of-staff Chris Hani, honouring him as: the first foot soldier of MK – and so he got another important name. They also went to Norway where he and June were reunited with their son Sello. Seeing the sick Tambo there however was heartbreaking.

When the first democratic election happened on 27 April 1994 Andrew and June proudly walked to the Selalani Junior School in Dube to cast their votes. At the inauguration of Mandela as the first president he knew this was what they fought for and was happy to be a member of the new parliament, serving on the Sports and Recreation Committee.

Mathebula presents Andrew’s life story vividly and with empathy. Those who come from the Free State can identify with the early life of Andrew’s family and the Sesotho culture as it was ingrained in everyday living. It gives a glimpse into the experience of urbanisation and how it opened up a different world to Andrew like school opportunities and political awareness. If you wonder what life was like in the townships, here you can get a good insight into daily activities, the practice of mqombothi brewing, police raids and more. It is mentioned that the Pimville homes were owned by residents, which may be disputed since private ownership of houses in townships was forbidden as far back as 1923 – an Act which also controlled other aspects of black people’s lives in urban areas. The researcher and history professional may know on what this ownership claim is based. We know that ownership only became possible as one result of the youth revolution of 1976.

You can also read more of Andrew’s observations and memories of the first townships (the name Soweto was only adopted in 1963) and urban areas. There was for example an influx of squatters and efforts to control it, daily life which included the brewing and hiding of traditional beer, police raids, the renting out of rooms for an income and more. The City of Johannesburg’s Non-European Affairs Department was the big controller, while township superintendents were each in charge of a number of houses with responsibilities of rent collection, the settling of disputes, as well as allocating houses and trading sites and more. One of their challenges was to communicate government policy and regulations to advisory boards, together with administrative changes and getting their support. Despite the best efforts of some sups the advisory board system was perceived as a grievance committee with no real powers (which was true). Sekile was on an advisory board member and an activist which helped Andrew to be well informed.

Headquarters of the Johannesburg Non-European Affairs Department (The Heritage Portal)

The famous James Sofasonke Mpanza was active in the Orlando Township and advisory board in those days and formed the Sofasonke Party. He was honoured as the father of the homeless because of his action in 1944 to establish the Masakeng settlement on the banks of Klipspruit next to Orlando East in protest against the lack of adequate housing provision by government / Johannesburg Council. Andrew was uncomfortable with Mpanza’s leadership style and both the ANC and CPSA condemned him as an opportunist using homeless people for his own ends (although it is also on record that, after his release from Robben Island, Sisulu did praise him as a pioneer). Mpanza then threatened the two groups with violence.

James Mpanza on his horse (Photograph displayed at James Mpanza House)

James Mpanza House (The Heritage Portal)

The active participation in Soweto advisory boards by the Sofasonkes – also long after Mpanza’s death – is not in the book, but common knowledge in Soweto’s history. According to some historians he called himself the Town Clerk of Masakane and collected money for services like the provision of hessian for building shacks, providing security and delivery of firewood. The Sofasonke Party’s involvement in local government politics continued after changes in the powers of ‘ma-bondas’ and in 1983 they virtually took over Soweto’s so-called black local authority. The last ‘councillors’ saw their careers come to an end on 13 January 1993. That was the last of the Party’s involvement in Soweto/ Johannesburg’s local government – a history still to be written. Mainly since the 1983 councils were unacceptable to other political groups and were regarded as ‘puppets’ of the Apartheid Government.

Andrew Mlangeni was there in Melrose for the launch of the biography and this ‘backroom boy’ did not look his age. He gave a great talk and signed purchased copies with a message written in a steady handwriting and emphasizing his testimony: I did what I did, not for myself, but for the people of South Africa.

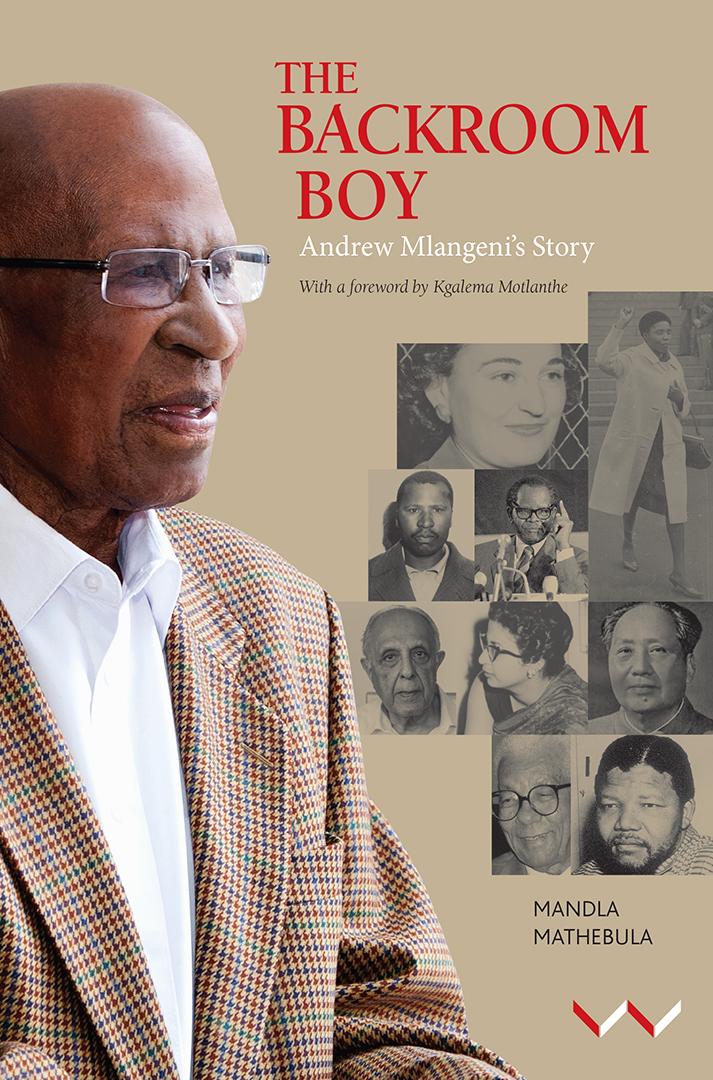

Book Cover (Wits University Press)

Originally compiled on 15 June 2017

Estelle Bester was a senior official in city management for many years. She has extensive experience as a private property facilitator and as a tourist guide in Soweto. She has a great passion for Soweto and its people.