Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

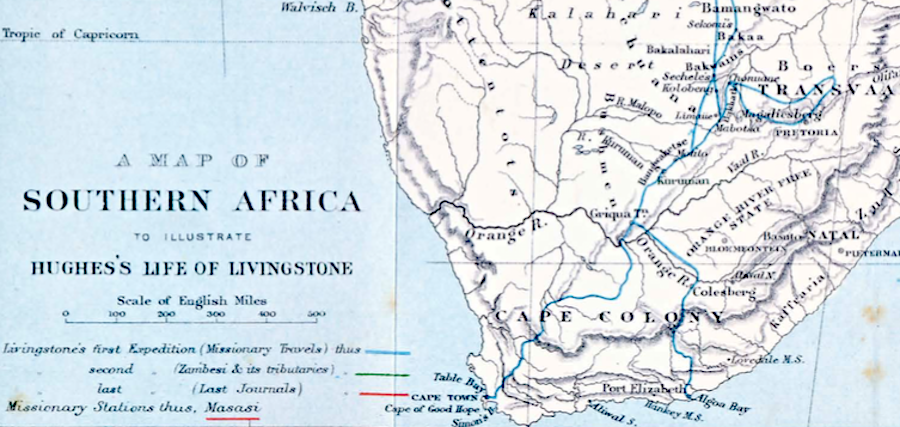

The first thing I did when researching this piece of writing was to look at a modern physical map of South Africa and envision that the urban areas and the modern road network shown thereupon were on a thin film that could be peeled away. What remained on the under layer were the physical features such as the coastline, rivers, escarpments and mountain ranges. It was a clean canvas on which I could put settlements on, but before I could do this I had to determine a date in history. I chose the year of 1841 as that was when the young David Livingstone, 28 years of age, first set foot on African soil.

Young David Livingstone

Livingstone is best remembered as the intrepid explorer who mapped out vast tracts of central Africa and who was thought lost in 'Darkest Africa' and then found on the shore of Lake Tanganyika at Ijiji (on 10th November 1871) by Henry Morton Stanley; his greeting to Livingstone of “Dr. Livingstone I presume?” has become one of most hackneyed (done to death) sayings in the English language.

When Dr. Livingstone came to Africa it was to be as a medical missionary, recruited by the London Missionary Society (LMS) and sent to join Robert Moffat at the Kuruman Mission, to preach the Gospel to the Tswana people. Kuruman was north of the Orange (Gariep) river and was therefore, at that time, outside the jurisdiction of the Cape Colony. How to get there was Livingstone’s quandary, which was resolved when he sailed into Algoa Bay, aboard the “George” sometime in April 1841 and stepped ashore at Port Elizabeth; the town established by the 1820 Settlers twenty-one years before and so named after the late wife of Sir Rufane Shaw Donkin the Acting Governor of the Cape Colony.

The LMS had a string of mission stations in the Eastern Cape and it was a matter of travelling, in no particular hurry, from one to the next. Before setting off Livingstone and fellow missionary William Ross had to organise transport and provisions for a journey that would take nearly three months. In his diary he wrote: “On my arrival in Port Elizabeth, the first thing I had to do was purchase an ox-wagon suitable for travel into the African interior. An ox-wagon costs £40 and trained oxen are £3 each”. They needed twelve oxen to pull the wagon and three locals were hired to act as guides and lead the oxen. They were able to begin their journey in mid-May as winter was approaching and Livingstone took to “trekking” with a great sense of pleasure, as we can surmise from one of his letters home: “I enjoy African Travel; the complete freedom of stopping where I want, lighting a fire to cook when I am hungry. The novelty of sleeping under the stars in thinly populated country makes a complete break from my cramped and regulated past existence in Scotland”. No doubt he took the Cape winter in his stride coming as he did from Blantyre, Scotland.

Trails had been blazed by “Trekboere” (migrating farmers) who were the first to settle the Eastern Cape (west of the Great Fish River) and at the time of David Livingstone’s arrival many were leaving in search of independence and pastures new north of the Orange River, far away from the meddlesome British authorities and the Border Wars with the Xhosa. Piet Retief was one such “Voortrekker” (pioneer) and his Manifesto of 1837 (reasons for leaving the Cape Colony) was printed in the Grahamstown Journal, in English translation from the Dutch (the language of the Trekboere).

The trails of previous ox-wagons were taken and towns where Livingstone and his party stopped over were Somerset East, Graaff-Reinet and Colesberg, where after the Orange River was forded (possibly at Allerman’s drift) and once on the far bank they were out of the Cape colony. Onward they went to stay at the mission at Philippolis (so named after Dr. John Philip, LMS Superintendent residing in Cape Town). On leaving they would have had to have backtracked to the Orange River and follow its course down stream along its north bank as far as the confluence with its main tributary, the Vaal River, where close by, up-stream, on the Vaal was another mission at Douglas. On fording the Vaal the party trekked onward to Griqua Town where they stayed briefly before pushing forward on their final leg to Kuruman arriving there on 31st July 1841. Between the towns mentioned there must have been many outspans as the maximum distance usually travelled in a day was a mere 20 miles (32 km)

What has been stated above suggests that there were no roads at the time let alone road signs and to get to a destination a compass and guides familiar with the topography (familiar landmarks) of the interior were a necessity. The town of Colesberg for instance was first known as Toverberg, after a prominent hill nearby easily seen from a distance by travellers. Toverberg is a Dutch word meaning Magic Mountain and it was so named because on first sighting of this hill on the horizon (at a distance of 25 miles or 40 km) it never appeared to get any closer as you approached it.

Kuruman oft called the “Fount of Christianity in Africa” has a natural fount - a gushing spring, known as the “Eye of Kuruman”, reputedly the largest in the southern hemisphere, providing 20 million litres of water a day (even in times of drought) and is the source of the Kuruman River. Human settlement around this oasis on the fringe of the Kalahari Desert has been from time immemorial, with the San people being the first inhabitants. It was a staging post on the Missionary Road, a trail heading northwards into the heart of Africa and was travelled by missionaries, explorers, hunters and traders heading towards the Zambezi River and beyond.

Book Cover

Kingsley Holgate (he of the biblical grey beard) who describes himself as a “romantic adventurer” is a modern day explorer who has made many epic trips across Africa. He has followed in Dr. Livingstone’s footsteps albeit in a Land Rover and his book “AFRICA In the footsteps of the Great Explorers” is a thoroughly good read. His Safaris into the heart of Africa with all of the “Mod Cons” of the 21st century only go to show what a fantastic feat of human endurance was accomplished by Dr. Livingstone on his several expeditions during the mid 19th century (1849-1873).

The road distance nowadays should one wish to drive from PE to Kuruman is roughly 950 km (595 miles) and the time taken should you be in any sort of a hurry would be 13 hours. Personally I would drive as far as Kimberley, stay over night, visit the Big Hole and Mining Museum the following morning and then pedal onto Kuruman in the afternoon arriving in time for a “sundowner” followed by dinner and a good bottle of wine. My preferred route (not necessarily the most direct) would be N2 east as far as Ncanha, then take the N10 all the way to Britstown, stopping before at De Aar to take in the railway junction. At Britstown turn right onto the N12 and stop over at Kimberley. After rest and recuperation and reliving the Kimberley diamond days it’s onward along the R31 to arrive safely in Kuruman just before dark. What a journey!

Map of Northern Cape showing the R31 road (On Route in South Africa)

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.