Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In the spring of 1941, the first ten thousand Italian prisoners of war (POWs) from the fronts of Ethiopia and Eritrea were brought to a camp, Zonderwater, near Cullinan [Ball, 1967]. Many of these POWs were responsible for the construction of passes like Chapman’s Peak and Bainskloof Pass. At Keerwater Camp, Worcester, 1500 POWs were used for construction of Du Toit’s Kloof Pass.

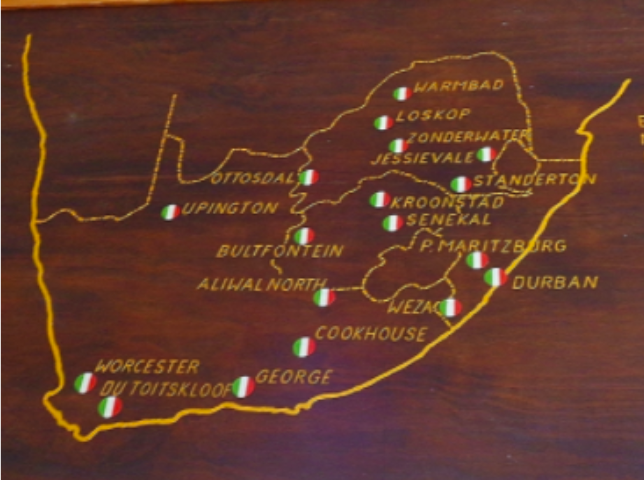

Record of Italian POW camps during Word War II (Zonderwater Museum)

Despite local folklore, no verifiable evidence exists of an Italian POW camp on the outskirts of Pringle Bay for road construction. No documentary evidence from authoritative sources confirms the existence of an Italian POW camp at present-day Glen Graig Conference Centre [Ball, 1967; Delport, 2013; Gorgatelli, 1989; Horn, 2013; Somma, 2013; http://www.zonderwater.com/en/].

Example of a common radar station access road (Bernard Price Institute)

Local African labour recruited, including women, used for roadbuilding (Harris, 2017)

Given the extremely classified nature of the coastal radar defences, strict precautionary security measures were put in place at the time. The Union Defence Force [UDF] had full and complete discretion over the use of the land, including the construction of buildings and roads that they deemed necessary, as well as the right to declare this land as prohibited to non-military personnel.

In the 1929 Geneva Convention relating to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, prisoners of war could be employed in public works which have no direct connection with the operations in the theatre of war. The Convention states that a structure may be military or civilian in character. A road is civilian in character, but a road leading to a military site certainly has a military purpose [Scmitt & Green, The Employment of Prisoners of War, 1964]. This prohibited the establishment of a POW camp for road construction at Pringle Bay.

Domestic attitudes towards Italian POWs fluctuated between hostility and sympathy. The UDF’s view was explicit: the Italians were the enemy. Given the secret nature of the location and the internal threat of the Ossewa Brandwag who helped Italian POWs escape from camps and hide them [Delport, 2013], it is highly unlikely to accept the presence of more than 200 Italian POWs [from 1941 to 1943] during radar station construction at the time. Kleynhans [2021] states that with the help of this network, German spies was established to gather military evidence using a variety of channels.

Several personal recollections of radar operations and life at the Hangklip, Silversands and Betty’s Bay radar sites do not refer to an existence of POWs situated at the present Glen Craig Conference Centre nor construction of roads [Brain, 1993; Clarence, Beryl, 1950; Hewitt, 1975, 1990; Lloyd, 1990a, 1993b; Mangin, & Lloyd, 1998].

Italy had capitulated and in April 1943 some 11 000 Italian POWs were repatriated to Europe on the troopship Queen Mary just about the time the radar stations at Silversands and Betty’s Bay were constructed.

Reports have emerged to the effect that the coastal road to the radar stations was built by Italian prisoners of war. This is not correct according to John Logan: “After the war, I spent many holidays and weekends at Hangklip. My father, Hugh Duval Logan, who befriended Jack Clarence, started to work on his land at Rooi Els, and hired groups of convicts of from five to ten members from the gaol." John recalls that: “He became interested in these men and took every possible opportunity to talk to them about their troubles. Most of these convicts had been sentenced to ‘life with hard labour’ which implied that they had committed very serious offences."

John Logan and Wim Myburgh

With support from the UDF, the Cape Provincial Administration commenced building this road in 1940. Using native (black) labour, the whole project was controlled by a Provincial Engineer by the name of Jan de Reuck. The route the road was to take along the steep sides of the coastal mountain road. At the outset, it seems that the men were transported to site daily from a temporary gaol near Gordon’s Bay. Later this plan involved far too great a delay and an interim gaol was built at Kogel Bay. This was a very primitive structure and evidence of its existence near the point where the stream at Kogel Bay debouches on to the beach has vanished. I remember seeing traces of these buildings early in 1946 when my family travelled out to Hangklip for the first time.

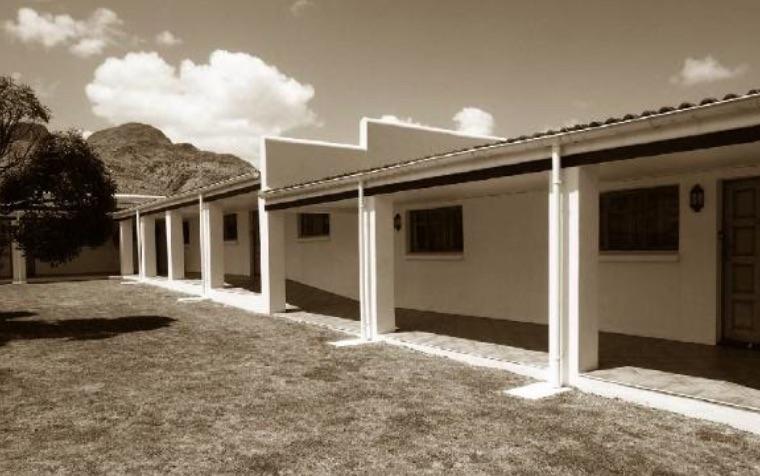

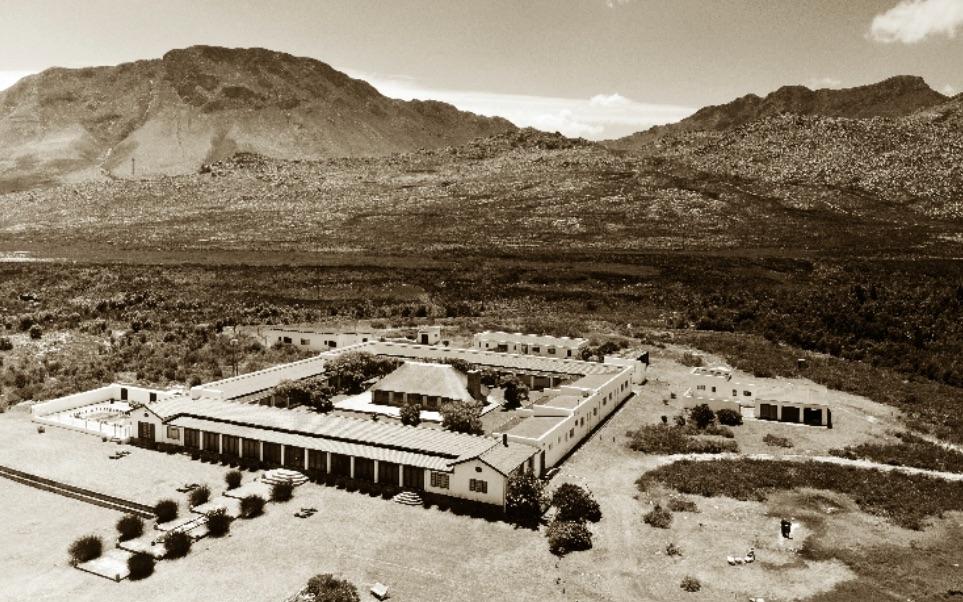

To regularise the situation and to make a more permanent place to house this labour force, it was decided to build a modern gaol beside the Main Road at Pringle Bay. Eventually this gaol was built and used to house around two hundred convicts. The quadrangle building [typical of prison planning layout] on the outskirts of Pringle Bay might have been used to house the convicts during the 40s.

The Glen Graig Conference Centre building (see main image) consists of a four-square block with the front portion used to house the Gaolers and guards needed for the management of the convicts. The three remaining blocks contained cells each housing about forty convicts and five smaller cells in a punishment block for recalcitrant or difficult men. In the centre of the building, a quadrangle contained a raised platform on which a pipeline system with sprinklers was mounted for convicts to wash their clothes – and themselves.

Structures that existed before the renovations (Sebastian and Toni Botha)

Images of Glen Graig in 2021 (Wim Myburgh)

John recalls that: “Years later in 1958 we were offered the use of one of the gaoler’s flats to build on our Rooi Els property, as a base from which to work from. The gaol had water borne sewerage and once this became blocked, I had the nasty task of opening the manholes on the upper level of the septic tank the size of small tennis court to clear the problem. The cost of feeding this number of convicts was a major factor and the land immediately below the gaol and along the bank of the Buffel’s River was levelled, irrigated, and used to produce almost all of the vegetables needed by the labour force”.

With changes in the Law after 1948, it ceased to be legally acceptable for offenders to be sentenced to hard labour and the Estate could no longer support the cost of housing two hundred convicts without their labour being available. The gaol was therefore abandoned.

In conclusion, the existence of an Italian POW camp at Pringle Bay during WWII is not supported by verifiable records, published authoritative sources and recollections just after the war, despite common folklore and inferences in local newsprint. The authors would welcome any additional evidence in support of the Italian POW presence during WWII coastal road construction between Steenbras River Mouth and Betty’s Bay.

Main image: Glen Graig Conference Centre. Site visit by Hendrik Bosman [drone], October 2021.

Dr Wim Myburgh: Early in his career he was a naval officer in the SA Navy and met Chris Dooner during this time. After this career, he obtained a Doctor Philosophiae [Psychology] at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University and practised as a consulting Industrial Psychologist in Cape Town. He maintained his interest in the military (publication. Dodd, N., Myburgh, W., Werner, J.L. & Mashatola, N.J. (2020). Psychological determinants of military student success). He acted as a guest lecturer at the South African Military Academy. He is a member of the Naval Heritage Trust.

References

- Ball, J.A. [1967]. Italian Prisoners of War in South Africa 1941 – 1947. Military History Journal 1 [1] 1967

- Brain, P. [1993]. South African radar in World War II. The SSS Radar Book Group.

- Clarence, Beryl. ‘Hello children’.1950.

- Delport, A. [2013]. Changing attitudes of South Africans towards Italy and its people during the Second World War, 1939 to 1945. Historia 58, 1, pp 167-190

- Hewitt, F.J. [1975]. South Africa's role in the development and use of Radar in World War II. Military History Journal, 3(3), (http://samilitaryhistory.org/vol033fh.html).

- Gorgatelli, P. [1989]. Tapes and Testimony: Making history of Italians in the Western Cape in the first half of the 20th century. MA dissertation, University of Cape Town.

- Horn, K. [2013]. Changing attitudes among South African prisoners-of-war towards their Italian captors during World War II (1942 – 1943). Scientia Militaria 40, 3, 200-221.

- Kleynhans, E.P. [2021]. Hitler’s Spies. Cape Town. Jonathan Ball Publishers SA

- Lloyd, S. [1990]. Life on the RADAR Stations: An Operator’s View. Online Access http://samilitaryhistory.org/diaries/radarshe.html

- Mangin, G. and Lloyd, S., [1998]. The Special Signal Services (SSS)’ Shield’ in Military History Journal, 11(2), (http://samilitaryhistory.org/vol112ml.html).

- Scmitt, M.N., & Green, L. {1964]. [eds.]. Levie on the Law of War. The Employment of Prisoners of War in, International Law Studies, 70.

- Somma, D.A. [2013]. Italian Prisoners of War in the South African Imagination: Contemporary Memory, History and Narrative. Doctoral dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

- Campo di concetramento in Sud Africa che accolse dal 1941 al 1947 oltre mila prigioniery italiani http://www.zonderwater.com/en/].

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.