Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

I was recently invited on a site visit to The Kagye Samye Dzong, Tibetan Buddhist Monastery and Centre in Kensington. It is a remarkable and little known heritage house in this suburb. The objective of the visit was to enable members of the Johannesburg East Joint Plans Committee of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation, together with members of the Kensington Residents Association to meet the distinguished Abbot Lama Yeshe Losal Rinpoche (the Chairman of the Ropka Trust and Buddhist monk) and his board and colleagues together with the architect Simi Theodorou.

Isabella Pingle, a unique estate agent in Kensington, brings groups together that are unlikely to connect in other ways. She is a Trustee of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and she promotes and celebrates the heritage of Kensington; she founded the Kensington Heritage Trust which works closely with the Kensington Residents Association. Isabella has convened this gathering; we are all masked and observing Covid conventions but it is a delight to be out and meeting heritage enthusiasts on a sunny July Saturday. The address is 34 Floss street, stands 7641 and 7642. It is a stone’s throw away from Roberts Avenue and Jeppe Boys School but it is a secluded, hard to find place as Floss Street turns a corner and runs to a dead end. The gates to the centre open off a cul-de-sac end of Floss and Good Hope Streets; a dozen cars already spill out of the small car parks in front and behind the house.

Ropka was founded in Tibet and is an international relief organization. Ropka is a Tibetan word meaning “help or friend”. Their objective is to develop projects to provide humanitarian aid to people in need around the world. The Ropka Trust (the Lama is the chairman) is the owner of the large Kensington Property on the ridge above Langermann Kop and Gunnion Pass. It is one of those hidden homes with a long history and now with a vision and a purpose, the Tibetan community are embarking on a substantial project expressing confidence and hope in their investment in a superb temple on the Kensington ridge.

The Abbot is also the Abbot of Kagyu Samyu Link, a major Tibetan Buddhist Monastery in Scotland and the hub of a network of centres for world peace and health around the world. This organization is established in the UK, Ireland, Iceland, Germany, Belgium, Spain, Italy, the DRC, Zimbabwe and South Africa.

The Ropka Trust purchased the Dix house in 1992 and has established a strong humanitarian presence in Kensington. It is the oldest of the established Buddhist centres in Southern Africa. As the Abbot comments: "It has been a force for good since it was first established more than 25 years ago”. He elaborates: “We have been able to open our doors to everyone, without discrimination based on race, gender, colour or faith". They offer a variety of programmes such as a soup kitchen and courses in Mindfulness, Tai Chi, Yoga and Therapy.

Plans are underway to build a Buddhist Temple in the grounds of Dix House. The organization wishes to promote harmony and see the temple as providing material and emotional support for all and be a resource for the local community and the wider Buddhist community. This development will be an extraordinary and welcome addition to the diverse mix of Johannesburg cultures and religions. The Abbot sees the Temple as a unique and iconic building that will contribute to the already impressive architectural and cultural heritage of Kensington and Johannesburg. They are hoping to move ahead quickly with a time scale of six months. The project will involve an investment of R10 million.

Our Johannesburg East Plans Committee of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation is pleased to support this endeavour.

The Abbot Lama Yesye Losal Rinpoche has written his memoirs From a Mountain in Tibet, a Monk’s Journey. I was presented with a pen by the Lama with his name and the details of his book – so this book has joined my reading list.

Book Cover

The Buddhist centre currently occupies a heritage home that dates back to 1906. This is House Dix. The intention is to preserve, conserve and restore the original house. The new temple will stand alongside the old Dix home.

History of Dix House

At this point I thought it might be helpful to explore the history of the Dix House. It is an underappreciated heritage home on the Kensington Ridge lying between Roberts Avenue and Albertina Sisulu Road (formerly Bezuidenhout Street, with a section named Kitchener Avenue). Isabella Pingle raised the profile of the property in her 2018 Kensington Heritage Map. The original address was Good Hope Street. It was a residence for the Dix family with public rooms on the ground floor, kitchen and pantry, and four bedrooms on the first floor with a single bathroom. Today the house has something of an institutional feel, as the centre spills out into rambling outbuildings, annexes and additions.

The 1905 plans - a residence in Kensington Estate for C Dix Esquire

Front of the Dix House (Kathy Munro)

Parking areas have been opened at the front of the house and at the rear; the bricked driveway running is lined with wonderful gnarled pepper trees. These trees would probably have been planted at the time the Dix house was built. Moulded concrete figurines in meditating poses have been placed around a couple of these trees. Sadly perhaps the oldest and most impressive of the trees will be sacrificed for the new development. I hope that at least one pepper tree will be saved as this genus of tree is part of Johannesburg’s history dating from a time when horses, stables and carriages were integral to suburban life. The aroma of the pepper trees was a deterrent to the flies attracted to horse manure. Click here to read more about the history of the Pepper tree. [Unfortunately the trees have felled. See the update at the bottom of this article.]

Grand Pepper Tree at Dix House (Kathy Munro and Archie Barnwell)

Tibetan Buddhist prayer flags stretch across the driveway from house to pepper trees. These prayer flags in red, blue, yellow, white and green represent the elements like air, fire, water and earth. White symbolises air, red is fire, green is water, yellow is earth and blue is wind. Prayers are carried by the wind.

The distinguishing features of the home are the open verandahs on three sides to take advantage of the cool breezes rising upwards from the valley below, a curious hexagonal observation turret above the south west bedroom almost like a witch's cap, and three substantial chimneys. The veranda is recessed under arches and some elegant Doric columns. The original windows are long sash windows. The front door has an Art Nouveau feel, with lovely art glass panels. The original roof would have been made of imported corrugated sheet iron, but at a later date was replaced with tiles. The turret is a charming curiosity - an attic retreat; Dix could have viewed the Kensington and Bez Valley scene and the rush of building activity in the valley below from this eyrie.

Front door Art Nouveau Glass Panels (Johannesburg Heritage Foundation)

The Turrett (Kathy Munro and Archie Barnwell)

Another oddity and folly in the garden is a small garden box with a decayed shingle roof said to cover the original well of the house; it is hardly a summer house so the story that it was originally a signal box and imported from Northern Scotland may just be true. There is also a pool in the garden; no longer for swimming it has been converted into a fish pond. This would have been a much later and very South African addition.

The small garden box (Archie Barnwell and Kathy Munro)

Pool / Fish pond at Dix House (Kathy Munro and Archie Barnwell)

The foundations of the house were constructed of local koppie stone to take account of the incline of the site. The north facing façade shows a bay window. The first floor window has been replaced.

The north facing façade (Kathy Munro)

Through the years the house has been altered with an additional wing added on the east side. The Parktown and Westcliff Heritage Trust (Johannesburg Heritage Foundation today) visited the house in 1993 and awarded it a B Heritage grading.

It is a spectacular location with a breathtaking view to the north overlooking the open veld of the steep ridge and a pathway known as Gunnion pass. Below lie the Kensington streets leading off Kitchener Avenue and one looks across to the suburb of Bezuidenhout Valley in the middle distance and across to the Observatory and Highlands ridges further north. The view to the far west is towards Judith’s Paarl, Bertrams, Yeoville and Hillbrow (the high rise blocks create a curtain screen in the far distance). For me the view out over these old Johannesburg suburbs from this property defines old but also evolving Johannesburg with that contrast between low rise family suburban dwellings inhabited by working class or aspiring middle class people; it is a cityscape that still gives a feel for what Johannesburg was like seventy to one hundred years ago; in contrast Hillbrow is an inner city suburb that became the epicentre of densely packed apartment blocks from the 1940s.

The breathtaking view (Kathy Munro)

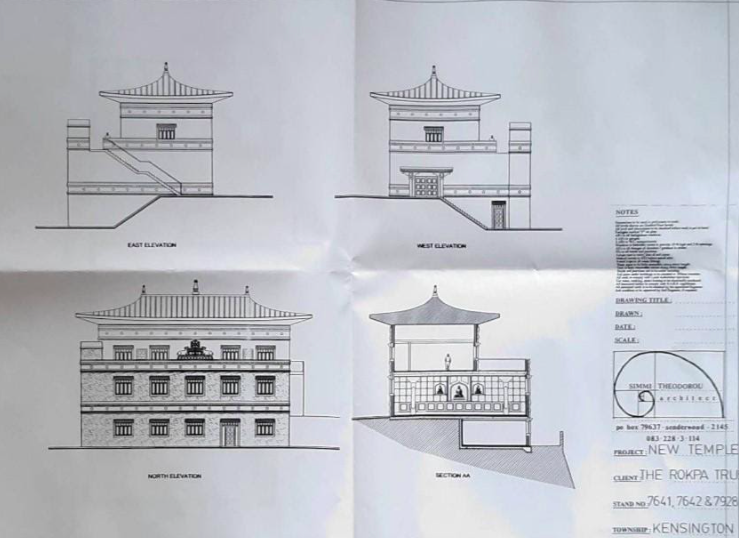

Below is the proposed plan for the new Buddhist temple. The architect is Simi Theodorou who is respectful of the traditions and style of the Buddhist religious structures and the antecedents to be found in Lhasam, with a pagoda line to the roof. Here is a case for blending old and new. For a heritage building to survive, thrive and be valued it has to be appreciated and find a new use and a meaningful purpose. In my view, now is the right moment to present the case for a much prized Johannesburg Heritage Foundation blue plaque for this property.

Proposed plans

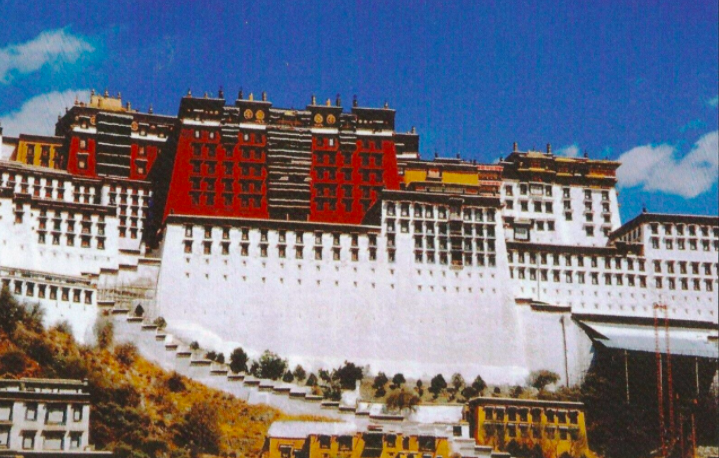

Postcard of the Tibet Lhasa Potala Palace

Who was Christopher William Dix?

Christopher William Dix, who commissioned this residence, had an interesting background. He arrived in Johannesburg with his wife Emily (known to her family as Molly) in 1895. He was born in Adelaide Australia in 1868 but was educated in England at Christ’s Hospital School and at Chatham House, a grammar school in Ramsgate. He married Emily Florence Gerald Pilditch in Surrey in 1893 and came to the Transvaal in 1895. Dix found employment as an official of the Post office of the Zuid Afrikaanse Republiek. He could well have worked at the Rissik Street Post office built in 1897 or he could have worked at the Jeppestown Post Office within walking distance of Troyeville. He and his wife lived on Op de Bergen Street in Troyeville, at that date an attractive suburb with some attractive homes.

Jeppestown Post Office (A Johannesburg Album)

An early photo of the Rissik Street Post Office (From Mining Camp to Metropolis)

With the outbreak of the Anglo Boer War in 1899, Dix found himself in an awkward situation as he was a British national working for the Kruger government; war broke out on 11th October and Dix refused to either enlist or be commandeered into a Boer commando. The Dix house in Troyeville was locked up and like thousands of other British subjects the family left for Durban. Emily Dix and a young daughter sailed for England and remained there for the duration of the war. Her family home was in Abberton, a village in the borough of Colchester, Essex. Johannesburg surrendered to the British in May 1900. The Dix family returned to Johannesburg and found their Troyeville home looted; a claim for compensation was submitted by Dix to the British Government but he was only paid out a small amount.

In October 1901 Dix joined the Witwatersrand Native Labour Association (WNLA), an organization formed by the Chamber of Mines to streamline the recruitment of African migrant labourers for the gold mines in remote tribal areas across Southern Africa. Formed in 1900, the immediate task of the British financiers, investors and the gold mine company promoters was to restart the mines of the Witwatersrand. Securing the gold mines for British interests was a critical objective of the War. The epic march of 7000 Zulu workers who left the Witwatersrand in October 1899, and walked back to Natal was an historic episode in the turmoil that hit Johannesburg as the war started. Now the task ahead was to bring back the 100 000 black workers who had retreated to their rural homesteads. But the first act of the Chamber of Mines when peace returned was to reduce wage rates for black mine labourers dropping the average rate of pay from the 43-44 shillings a month paid before the War to a minimum wage of 30 shillings a month or 1 shilling a day. The maximum wage was 35 shillings or 1s 2d a day. Board and lodging was provided free but in the mine compounds for migrant workers; these were for men only. The costs of passes and travelling expenses to bring workers from their rural homes to the Witwatersrand was carried now by the employees and not recovered from deductions from workers’ pay. As John Lang points out in his book on the History of the Chamber of Mines “Bullion”, it was a decision not based on a sound understanding of the post war circumstances on the Rand. After the war the mining industry had great difficulty recruiting sufficient African mine workers on these terms locally; the labour shortage was exacerbated and so the decision was taken to recruit Chinese miners from the mainland of China as contract labourers. This is the background to Dix's working world. He became the Secretary of the WNLA and remained with the organisation until his death in 1916.

Chinese Miners (A Johannesburg Album)

Dix evidently moved from Troyeville to Kensington sometime after taking up employment with the WNLA. It was an appealing choice in the early 20th century as Kensington was a new suburb to the east of the town, about two miles from Market Square. We noted that the plans of the Dix residence are dated 1905 and the house was completed in 1906. It lies to the South of Bez valley and spans the line of the Witwatersrand ridges. The land was originally part of the Bezuidenhout farm of Doornfontein.

Langermann and the development of Kensington

Max Langermann obtained a lease to create a proposed township in 1896/97. He named it Kensington after the London borough. An 1899 map of the Witwatersrand gold fields (Wood and Ortlepp) features “Kensington proposed township” but the Anglo Boer War clearly disrupted plans for development. Nonetheless, Langermann is considered to be the father of Kensington and today he is remembered in Langermann Kop (incorrectly spelt as Langerman) and Langermann Drive.

The view from Langermann Kop (The Heritage Portal)

Langermann hailed from Bavaria Germany and arrived on the Witwatersrand in 1886. He was an early mining entrepreneur and recognized as a Rand Pioneer (he was a member of the Rand Pioneers Association). Langermann was a member of the Reform Committee of Uitlanders who in 1895 were involved in the Jameson Raid debacle. He was imprisoned and fined for his participation in that attempted coup. He was a man of importance in early Johannesburg. After the Boer War, Langermann sat on the newly formed Johannesburg Town Council between 1903 and 1905. He played a leading role in the establishment of the Jewish Board of Deputies in 1903 and was its first president.

In 1902 the Kensington Estate Co Ltd (Langermann was the Chairman) purchased Langermann’s rights; by 1903 a township had been listed. James B Tucker and WHA Pritchard surveyed the township. Stands were sold on a lease or a freehold basis. It was promoted as close to the epicentre of the city with great view sites, grand mountainous koppies and open rolling veld, picturesque avenues and roads with park like prospects. Kensington was marketed as a “health resort”, noted for the cool of summer and away from the dust storms and sand blown off the growing mine dumps. The main roads through Kensington were named for the British Anglo Boer War generals, Lord Roberts and Lord Kitchener. 13 acres of park was laid out by the Kensington Estate Company in 1903 and named for Cecil John Rhodes. These prominent names gave Kensington a rather British colonial ambience.

Rhodes Park (Kensington Spring Fair)

In 1903 Langermann was also the donor of four stands on Benbow Street with the idea of establishing a Jewish orphanage. A building was erected in 1905 and accommodated the first 20 children. In 1923 the orphanage / children's home moved to the Phillips home Arcadia in Parktown (also designed by Herbert Baker).

Villa Arcadia (The Heritage Portal)

Many Kensington streets were named for British battleships of the Edwardian era and retain those names. Lynx was named for a British destroyer launched in 1894. Other British Admiralty cruisers whose names were adopted for street names in Kensington were for example, the Minerva, Marathon, Leda, Benbow, Collingwood, Royal Oak, Montague, Nymphe, Orion and Osprey. Signs of a tidy mind in the surveying and naming of Kensington is the fact that the streets run in alphabetical order.

Dix gave his address as Good Hope Street, Kensington in the 1908 Who’s Who. Anna Smith says the street was named for a British cruiser, the Good Hope launched in 1910, so the question arises was there another ship by the name of Good Hope pre 1910? In turn the name of the ship referenced the Cape of Good Hope. The address of the Dix house today is Floss Street. It was named for a village named Floss in Southern Bavaria where Max Langermann was born. During the First World War, street names with a German connection were changed, for example, Kaiser Wilhelm Street in the city centre became King George Street, Schmidt Street in Observatory was renamed Mons Road after the first battle of the First World War fought between Germany and the British allies in August 1914.

A prominent landmark in Kensington that cannot be missed is the Kensington Sanatorium, at the Commissioner Street end of Roberts Avenue (23 Roberts Avenue), designed by the architect John Francis Beardwood in 1897 (Artefacts gives the date as 1905). It was built and run by the Catholic French sisters of the Holy Family from commencement until 1915. They too moved to Parktown and hence the origins of the Kenridge Clinic on Eton Road, which today is the Donald Gordon Hospital. The popular name of the Sanatorium and one that persists to the present is “the pink fairy castle” as it has something of a chateau like air with the turreted corner wing and ornate spires. The design echoes that of the Parktown Convent, an institution also established by the Holy Family order of nuns in 1905 and also designed by Beardwood. Max Langermann, the founder of Kensington died at the Kensington Sanatorium in 1919 and is buried in Braamfontein cemetery. This private hospital still operates and today has the name, Life Healthcare New Kensington Clinic.

An old postcard of the Kensington Sanitarium

Parktown Convent / Holy Family College (The Heritage Portal)

The blue plaque for the Kensington Sanatorium was awarded by the Johannesburg 100 committee in 1986 and here the architects are given as Aburrow and Treeby; this is an error.

Dix and his family move to Parktown

Dix did not live for many years in Kensington; with a young family of two daughters and deepening business connections to influential mining and businessmen of Edwardian Johannesburg, Dix was clearly upwardly mobile. The 1910 Voters Roll records C W Dix as resident in Escombe Avenue, Parktown West. However, although Dix had relocated to Parktown, he was still recorded as the owner of the Kensington property in the 1913 Valuation Roll.

The Witwatersrand Native Labour Association engaged Baker and Fleming to design alterations to their offices and compound in Eloff Street in 1911. We begin to glimpse the close links and networking of the top business and mining men in Johannesburg around this time. The Board of Management of the WNLA included at various times prominent players such as Drummond Chaplin (who commissioned Herbert Baker to design his home Marienhof in Parktown – today Brenthurst), Sir George Farrar (Baker designed his home Bedford Court on Bedford Farm – today St Andrews School for Girls), Sir Percy Fitzpatrick, Sir Julius Jeppe (his home was Friedenheim in Belgravia), Sir William Dalrymple (his home Glenshiel was designed by Baker and Fleming in 1910). Baker and his wife Florence Edmeades (his cousin) married in 1904 and he designed his own house, Stonehouse in Rockridge Road. These were men who cooperated in the city, probably socialised at the Rand Club and at dinner parties in their new homes in Parktown and Westcliff; their wives too connected at tea and tennis parties and their children went to the same boys and girls schools.

An old painting of Bedford Court

An old postcard of Glenshiel. The Haggies were later owners.

Stonehouse (The Heritage Portal)

Dix was the WNLA man in negotiations with Baker and Fleming and in 1910 those conversations extended to commissioning the practice to design a new house for the Dix family in Sherborne Road, Parktown. The architects provided the complete working drawings for the house for the modest fee of 2.5% of the contract house, but did not undertake supervision. Baker normally worked on a fee of 4.5% to 5%. Marcus Holmes, who many years later restored the Sherborne Road House, comments: “remember that Baker and Fleming had really good builders who knew all of his standard details, and Baker houses were not cheap. The project administration and site inspections were minimal, the contractors did most of what was necessary and there was very little time consuming confrontations with clients or contractors and a need to redo jobs.“ Marcus elaborated: “Understand too that Baker was involved in almost no speculative work, and neither did he have to do endless design review or reworks. He would regularly pick up work at dinner parties and move on to sketching ideas after dinner and then speedily have the drawings in his office by the next day”. The technical documentation was limited and much was left to the education, insights and skills of his contractors and their artisans!

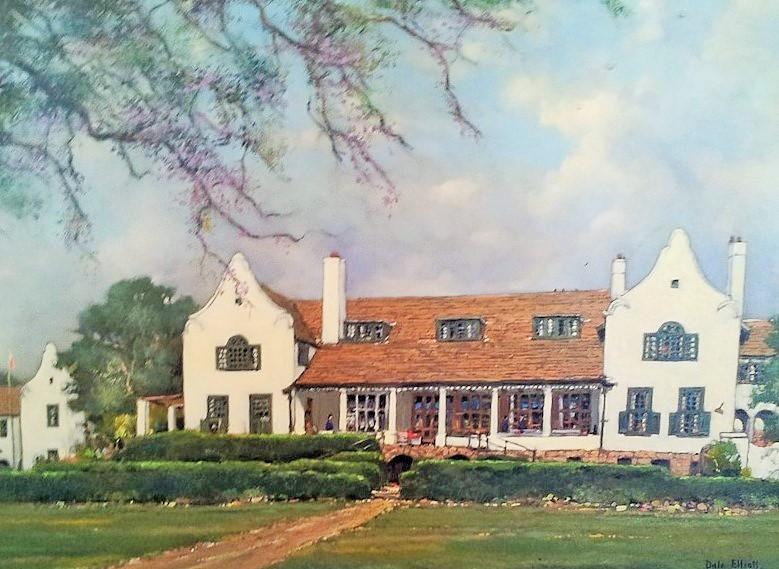

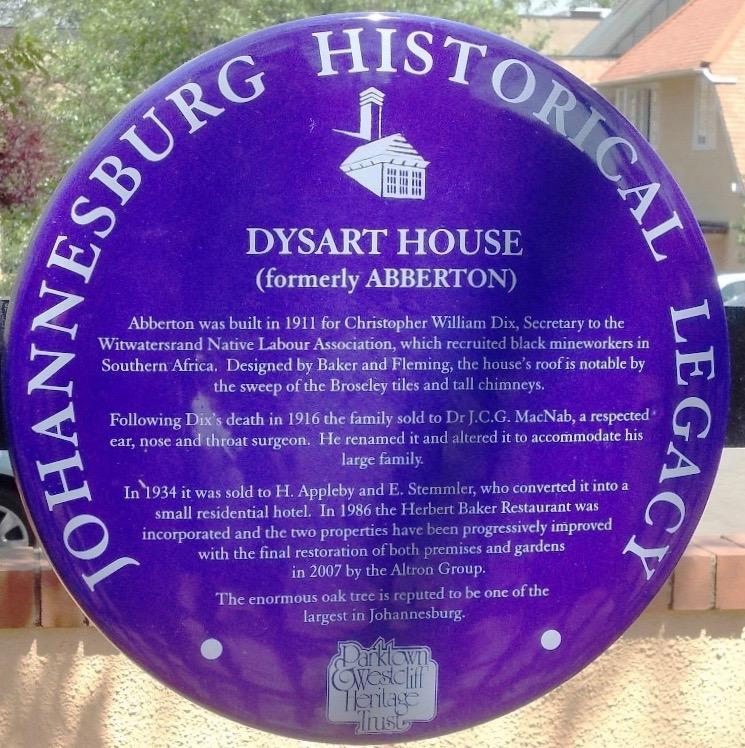

This house, Abberton (later renamed Dysart) built in 1911, still stands and although extended at a later date, the design and style of the original house remains in tact. It is a good example of a relatively modest Arts and Crafts style double storey house. The original house, as can be seen from the photograph is symmetrical. It has a blue plaque and the history of this house has been carefully documented in a 1996 heritage report compiled by Fassler, Kamstra and Holmes for the National Monuments Council.

Dysart House (The Heritage Portal)

Blue Plaque

The scale of accommodation did not differ hugely from the Kensington home and comprised a drawing room, a dining room, kitchen, three upstairs bedrooms and a playroom, pantry, bathroom, scullery and an earth closet. A tennis court was added in 1915. The house was named Abberton after Emily’s home village in greater Colchester, Essex. There were outbuildings and a stable for horses.

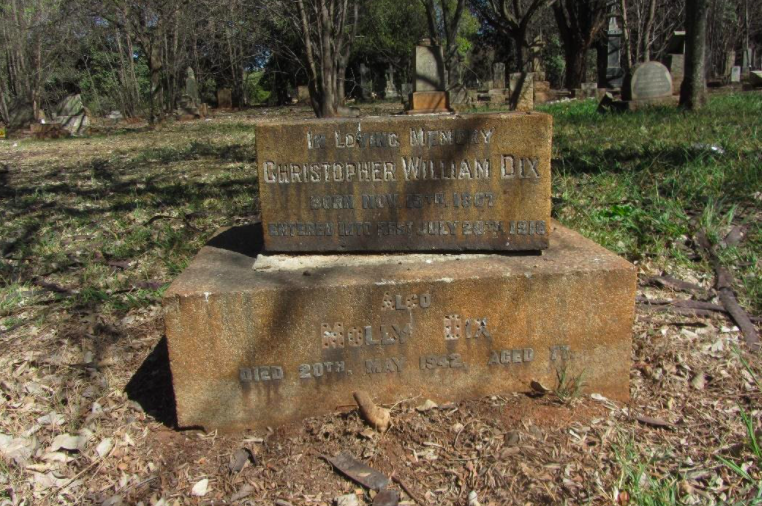

Sadly, the Dix family did not inhabit the Parktown house for long. Dix took ill in 1915 and died on 26th July 1916. He was buried in Brixton Cemetery.

The grave of Christopher William Dix who died in 1916 and his wife Emily (Molly) who died in 1942 (Sarah Welham)

Dix’s wife Emily (also called Molly) inherited her husbands estate and possessions. Later in 1916 she sold the Parktown property to Dr JGG Macnab and his wife Mabel. Records show that Mrs Dix moved to the Macnab house in Berea at 24 York Street and lived there from 1916 to 1920. Dr Macnab was an ear nose and throat surgeon who came from Lanarkshire Scotland; he held an honorary appointment as a ENT surgeon at the Johannesburg Hospital from 1912 until his retirement in 1926. They renamed the house in Sherborne Road Dysart House. The Macnabs had six children and in 1918 added five rooms in a west wing, also designed by Baker and Fleming. Dysart is a town in Scotland near Kirkcaldy, Fife. In the 1930s, Dysart house became a residential hotel / boarding house. Dr Macnab died in Durban in 1934.

Returning to the Kensington Property

A Jeppe Girls School History project says that at some stage of its history the Dix House was a nursing or a convalescent home and noting the proximity to the Kensington Sanatorium this is a perfectly feasible possibility. The valuation rolls provide a line up of the later owners. They were Thomas Sneddon (1925), JGT Watson (1931), TS Nelson (1937), AJ Wiles (1955) and Thora Ford and Gloudina Maria Pienaar (1966). The last private owner prior to purchase by the Ropka Trust in 1992 was Thora Ford who had a reputation for community mindedness.

In conclusion, from a heritage perspective it is unusual to have two renowned homes linked to one man, CW Dix. It is even more unusual that both should have survived. The Kensington house, now a Buddhist centre and about to stand proudly alongside a new temple merits a blue plaque in order that the story of the first owner Christopher Dix and his many complexities is not forgotten.

Update after compiling the article

I visited the Buddhist centre / House Dix on 13th August 2021 and was somewhat dismayed to discover that demolition of the outbuildings has begun; the Dix House remains but all the pepper trees have been felled. The sadness is that whilst I was informed during my first visit that one tree would be sacrificed this is not the case and 100 plus year trees which gave this house a context and ambience have been lost. Why do so many contemporary architects refuse to see the value of a green life? Ancient trees should be preserved and protected. The building team have moved ahead with demolition without the necessary permits from the Provincial Heritage Resource Authority Gauteng (PHRAG) or the Johannesburg City Building Department being in place.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.

Sources

- Holmden’s register of Johannesburg – Randburg and Sandton. 10th edition, no date circa 1970

- Kensington Heritage – Isabella Pingle - Heritage Map of Kensington, 2018

- Plans for the original Dix house

- Letter of motivation for a Buddhist Temple - 30 July 2021 from the Abbot Lama Yeshe Losal Rinpoche to interested stakeholders; plans for the new Temple

- John Lang, Bullion Johannesburg Men, Mines and the challenge of Conflict, Jonathan Ball, 1986

- Anna Smith, Johannesburg Street Names (Juta, 1971)

- Fassler Kamstra and Holmes Report on Dysart House, 6 Sherborne Road, Parktown, Johannesburg - 1996 Submission to the Northern Regional Committee of the National Monuments Council (archive of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation)

- 1908 The South African Who’s Who for entry on Christopher William Dix

- Archive documents on Dix House and Dysart House held by the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation, supplied by Di Steele - including article by Dennis Gordon, A Knock at the Door - photocopy article, no date but appears to come from Mining Survey - a useful source on the Witwatersrand Native labour Association.

- Conversation with Marcus Holmes, Heritage architect, 2021, Johannesburg.

- Online websites about the Ropka Trust and the Buddhist Centre in Johannesburg and Choje Lama Yeshe Losal Rinpoche, the Chairman of the Ropka Trust

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.