Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

This interesting and well attended talk, the 1st one at the Northern Branch of the Archaeological Society for 2023, adressed the search for rock paintings of unicorns, (the kind familiar in European myths) and independent of one-horned creatures in the beliefs of indigenous Southern African peoples. There were numerous such searches, but David focused on one of these as an example. He concentrated on the facsimile of an alleged ‘unicorn’ that appeared in the 1801 edition of the well-known book of Sir John Barrow, An Account of Travels into the Interior of Southern Africa.

The Barrow facsimile of a unicorn, clearly a European image, rather than a San rock painting

In European medieval times, unicorns were associated with Christian sanctity, because of their perceived purity, and any remnants of them, real or imagined, became sought after religious relics. Therefore, John Barrow’s facsimile of a rock painting detailing a unicorn, which he had apparently copied from a rock shelter along the Tarka River, south of the Stormberg, elicited great interest.

Barrow (1764 – 1848) arrived at the Cape in May 1797, as one of the private secretaries to the new Governor of the recently conquered Cape Colony, Lord George Macartney. In the course of his duties, from July 1897 to January 1898, he travelled to Graaff Reinet, Algoa Bay and to Ngqika’s kraal beyond the Keiskamma River, before returning to Cape Town by way of the Little Karoo. Subsequently, he described these travels in the above book.

Some of the criticism of Barrow’s facsimile of the unicorn rock painting, was that possibly the one horn obscured the other, or that rock paintings of ‘unicorns’ often turned out to be that of gemsbok or poorly preserved eland.

Geographic area covered by David’s talk

Although in the modern era we know that the legendary unicorn never existed, the question remains: what rock painting of an animal or representation of animal, did Barrow observe that made him think it was of a unicorn?

It was unlikely that the unicorn image could have derived from a gemsbok, as such antelopes were limited to the western areas of the Eastern Cape, the Western Cape, and the Northern Cape.

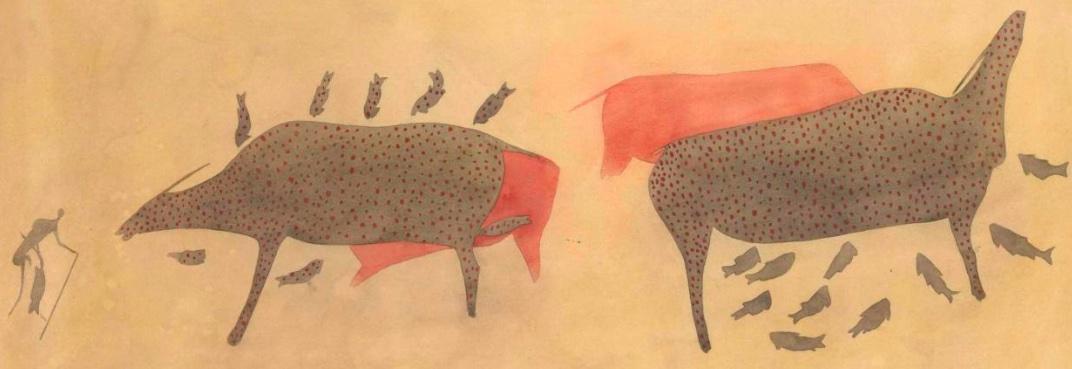

To show how the idea of European unicorns differed from South African ‘unicorns’, David presented photos of various rock paintings that indicated there were many renderings by the San, of one-horned antelopes. The role of these images in South Africa’s unicorn lore has gone largely unappreciated: they were often dismissed and the connection to local beliefs was not realised.

Dorothea Bleek (1873 – 1948), an early rock art researcher and commentator on the San, was the first to postulate that such rock paintings might not have been of actual antelopes, but more likely of mythical rain animals, part to the San’s spiritual beliefs. She was familiar with these beliefs because of the work by her father Wilhelm Bleek and aunt, Lucy Lloyd with |Xam San people.

To the San, rain animals were the embodiment of rain. To bring about the rains, the |Xam rain makers captured and killed such animals, even if only metaphorically speaking.

Dorothea Bleek – Were these San images of mythical rain animals? Note the fishes surrounding the antelope and attached to the human-like figure to the left.

The London Missionary Society’s Johannes van der Kemp also referred to an unknown animal that the Khoekhoen called ‘kamma’. Van der Kemp described it as follows: ‘It was never caught nor shot, as it is by its swiftness unapproachable; it has the form of a horse, and is streaked, but finer than the [mountain zebra]; its footsteps [are] like that of a horse.’

David then posed the question whether this so-called ‘kamma’ - although it did not seem to have a horn - might have been a mythical rain animal? He argued that it could well have been the case, because:

- ‘Kamma’ means water in Khoe languages, as in the name of the Keiskamma River (Keis = sand and Kamma = river or water) in the Eastern Cape; and

- According to the 18th century Dutch East India Company soldier, scientist and explorer, Robert Jacob Gordon (1743 – 1795), the Cape Khoekhoe word for water was Ćamma.

His conclusion is that, here, water refers to a water being or animal, such as rain animals or the personified Rain that appears in |Xam myths.

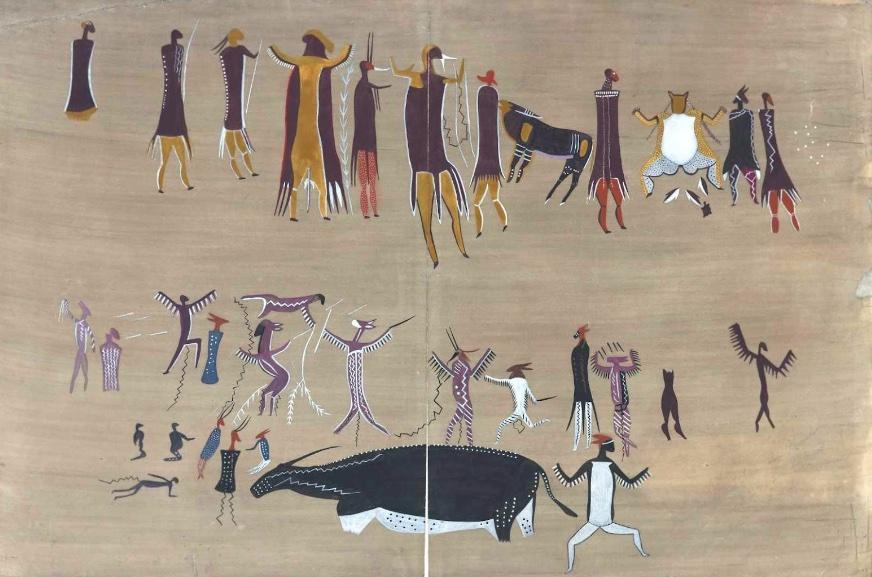

Additional evidence of the one-horned rain animal comes from an account recorded by Dorothea Bleek of a discussion with an unnamed |Xam narrator about one of George William Stow’s rock art copies, in which mention is made of a girl who was changed into a frog because she ate something that she should not have eaten. While the myth is one version of tales about relationships between pubescent girls and the Rain, the name of the thing the girl ate was recorded as ‘touken’.

The next question David addresses is what is, or was ‘touken’? One possibility is that it meant, as published by Dorothea Bleek, a ‘ground food’. Unfortunately, this could not be confirmed because Dorothea Bleek’s, A Bushman Dictionary, published in 1956, does not contain this term.

But in another recorded narrative, the ‘waterchildren’s story, the girl eats waterchildren – the calf-like offspring of what the San called rain-bulls and rain-cows.

David then broke the term down into the original San words.

The singular |Xam word for waterchild is !kwa:-ʘpwa (literally, ‘water child’). But the plural for children of the water is !kwa:-ka !kaukǝn (literally ‘children of the rain’). Does this mean ‘touken’ should actually mean !kaukǝn (children of the rain)?

If the rain-animal is a one-horned antelope-like creature, could !kaukǝn have been in this context, the offspring of the mythical rain animals with one horn?

The main image shown above of Stow’s copies was said by an unnamed |Xam informant to illustrate the water (i.e. the one-horned black rain animal in the foreground) to be destroying the people and turning them into frogs, because a girl had eaten ‘touken’ or perhaps as David argued, the rain’s !kaukǝn (or children) – just like in the narratives about the girl who ate the water’s children when she shouldn’t have.

David drew a distinction between classical European unicorns and those so-called ‘unicorns’ which became to form part of South Africa’s unicorn lore. In the colonial period, there was much unrealised confusion about unicorns. Europeans searched for the unicorns of their myths without realizing the uncanny resemblance between their unicorns and what appeared to have been the one-horned antelope-like rain animals in San belief. The rock paintings and San comments help us to appreciate the similarities and the differences. The creatures in the rock paintings are rain animals not unicorns.

David Witelson is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Rock Art Research Institute at Wits. He obtained his PhD in 2022, on Rock Art and Performance in the Stormberg.

A more detailed version of his talk will appear shortly in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal 2023, entitled ‘Revisiting the South African unicorn: rock art, natural history, and colonial misunderstandings of indigenous realities.’

Report by SJ de Klerk, Chairperson of the Northern Branch of the Archaeological Society, with images provided by Dr David Witelson.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.