Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Occasionally South African swop shops (pawn shops) have some historic photographic gems on offer, as was the experience just prior to Covid-19 lockdown at one such Cape Town based swop shop. The owner of the shop went scratching when asked for old photographs by the author.

Out came a box with some significant historical images, amongst them four photographs relating to a single South African maritime catastrophe.

1) Catastrophes photographed

Early catastrophes were popular photographic events. World-wide a variety of examples exists of disasters photographically captured - be that the consequences of blizzards, hailstorms, floods, fires, earthquakes, air or shipping disasters. Two immediate examples that come to mind are the San Francisco earthquake (1906) and the Hindenburg air disaster (1937).

A quick search on South African natural catastrophes from before 1920 indicates that no curated collections of such images are in existence. One man-made disaster which was well documented photographically was the Johannesburg dynamite explosion of February 1896. The underlying theme of this article is however that of a natural disaster that was photographed.

Braamfontein Dynamite Explosion (A Johannesburg Album)

Some South African photographic evidence of natural disasters do exist, also in the form of picture postcards, such as the Pretoria hailstorm (November 1913) or the Standerton floods (January 1911).

There was money to be made from photographing catastrophic events. It was a case of the photographer being at the right place at the right time. Photographers would have rushed out to photograph the aftermath of such event. The resultant images were in high demand by local citizens who would have acquired the images as part of their own personal “I was there” experience.

This is the primary reason why such images still surface occasionally today. Family members, who can no longer relate to these images acquired by earlier family, would discard them.

As a single item, any such image is near meaningless, but collating a number of images that relates to the same event becomes more meaningful.

Although not often on the receiving end of natural disasters, South Africa, compared to some other continents is not as prone to major natural disasters – at least prior to the 1920s.

The photographs presented below, captured by a singly photographic establishment, namely the Horwich Brothers, may well be the first South African photographic portfolio produced of a natural catastrophe.

2) Algoa Bay - Port Elizabeth

Port Elizabeth (Gqeberha today), based on the South African east coast (part of the Eastern Cape) was established during 1820 as a British settlement around Fort Frederick – suggested to be the oldest British building in southern Africa (built during 1799). The town finally became incorporated during 1861. Sir Rufane Donkin, the acting governor of the Cape Colony, named the town after his deceased wife Lady Elizabeth.

Port Elizabeth also happens to be renowned for its shipwrecks. The most calamitous ones were as a consequence of south-easterly gales in Algoa Bay. In an age of sail, ships were largely at the mercy of the weather. Gusting winds resulted in ships frequently being drive ashore after having lost anchor.

Exacerbating the situation was that the majority of the population of that era lacked swimming skills. Compounding that was the disregard for safety equipment aboard ships such as life vests and lifeboats.

The curve of the Bay towards North End is often referred to as the “bight”, an old English word. The North End bight was a notorious graveyard for wrecked ships.

And 1902 was no different. With some 38 ships riding anchor in Algoa Bay, a gale force south easterly wind came up during the evening of 31 August, causing absolute havoc and destruction.

3) The Great Gale of 1902

Regarded as the most devastating in South African maritime history was the hurricane (today referred to as the Great Gale) that hit Algoa Bay (Port Elizabeth) during August of 1902, resulting in the destruction of some 18 ships and numerous other smaller craft with the loss of 60 lives.

Though there have been other instances with greater loss of life, never before or since have so many ships come to grief simultaneously on the treacherous South African coastline.

Shortly before midnight that evening, town folk were awakened by a booming cannon shot. Most residents understood the significance of this shot. It had been fired to summon the lifeboat crew after the first blue distress signal was seen streaking across the dark, forbidding sky. It was also the signal for the curious residents of the town to congregate on the beach to witness the night of high drama unfolding.

The local rescue team went to the shoreline to see what they could do. In spite of their efforts the wind made it almost impossible to get lines to the distressed ships.

Huge waves kept battering the ships and several of them began to drift onto the bight of the bay.

This disaster is recorded as follows in the Eastern Province Herald of Tuesday 2nd September 1902:

Never before in its history has this port suffered under such overwhelming disaster as we record today. On Sunday morning some 38 craft rode at anchor under the leaden sky. Heavy rains had fallen, and the wind gradually rose until, as the shadows of evening hid the shipping from view, a fresh gale was blowing in from the south-east, which, as the midnight hour was reached, had developed into a hurricane. As the turmoil of wind and wave continued, so the toll of ships mounted, until 18 vessels were aground, with a raging sea adding a high toll of human lives.

The disaster was significantly newsworthy for the New York Times in that they also reported on the great gale in their 2 September 1902 publication:

18 Vessels, mostly sailing craft, have been drive ashore in a gale in Port Elizabeth. Four of them were dashed to pieces and all the members of the crews of these vessels were lost. Two tugs are also reported to have foundered and about 20 lighters are ashore. It is feared that there has been great loss of life. Sir John Gordon Sprigg, the Premier said in the house of assembly this afternoon that he feared that the loss of life from the gale would be enormous. 50 bodies have already washed ashore. The storm broke shortly before midnight last night and was accompanied by a deluge of rain and brilliant lighting. The night was very dark. Several tugs went out to the assistance of the endangered vessels, but nothing was visible from shore at Port Elizabeth, except the continual flashes of rockets as signals of distress. Daylight revealed the beach at the north end of Algoa Bay strewn with vessels lying high and dry, while other were in the surf and being swept by the huge breakers. With the exception of four vessels, which foundered with all hands, every sailing vessel in the roadstead was ashore by midday. Many steamships, after weathering the storm all night, steamed out to sea at daybreak.

Well-known Port Elizabeth historian Redgrave (1947), recorded this tragedy as follows:

Finally came the last terrible disaster of September 1902. One Sunday morning, some thirty-eight craft rode at anchor ‘neath a leaden sky. Heavy rain had fallen, and the wind gradually rose until, as the shadows of evening hid the shipping from view, a fresh gale was blowing in from the south-east, which later developed into a hurricane. Towards midnight, blue lights from ships in distress streaked across the black sky, followed by the hoarse sound of detonators arousing the sleeping citizens to the fact that urgent help was needed on the beaches, but such was the force of the gale that assistance was well-nigh impossible. No small craft could survive in such sea!

Before dawn, five vessels had crashed up on the shore, and as the cold grey morning broke, several more met their doom. Huge waves swept over the ships from stem to stern and burst in terrible cascades over the foundering wrecks, and the North End beach from the Gas Works to the ancient wreck of the Jarawar was one panorama of shattered shipping. Huge four masted ships and stately barques shared in the dreadful chaos.

One of the most pitiful sights was that of some seven or eight men and the Captain’s wife who were seen clinging to the bowsprit of one of the wrecks which was exposed to the full fury of the sea. One of the men was observed to slip down a dangling rope and drop into the sea. He struck out bravely for the beach, but a mountain of foam bore him on its crest to be seen for a moment and then lost to sight forever. Later another threw himself into the vortex of foam, only to be dashed to death against the floating timber. There came a crash, and the hull of the ship went into two, and they were swept from their fancies security where they had clung for endless hours with that pertinacity of purpose which the grim battle for life creates. Those ashore stood aghast with chill suspense and hearts full of fear as they watched helpless the awful struggle in which the cruel sea claimed its victims one by one until none was left.

Attention was then diverted to some half-dozen men who crouched beneath the shelter of what was once a vessel. A line from the rocket was fired and the line passed right over the heads of those clinging to the wreck. But time had told, fatigue had so done its work that the unfortunate men had not the strength left to pull in the lifeline. Efforts were made to rouse the despairing victims by shouting words of encouragement across the breakers to a last effort, but it was useless. Only one plunged into the sea and reached the outstretched hand of the first of a number of men who had waded into the waters to form a line at great risk to their own lives.

Then followed dark tragedy. Another man was seen to seize the line and struggle for the shore. Six of the spectators went out on a line to his rescue and were straining to maintain themselves against the backwash of the waves. A wild cry arose from the crowd as it was seen with horror that the line had broken and that the rescuers were now engaged in a life and death struggle from which one emerged victorious; the other five perished in their gallant efforts. In the presence of such tragedy, strong men shook with emotion and the women burst into tears.

Throughout the following morning and evening, body after body was washed ashore, some almost beyond recognition through the injuries received from submerged rocks and floating spars.

Such were the efforts of the last devastating gale that swept the shores of Algoa Bay, but with the erection of the breakwater and the spacious jetties, these terrible south-east gales have been robbed of their terrors and ships now safely berthed, mock at the fiercest hurricane.

During the calamity, four local men, Frank Gregory, A. I. McEwan, E. Hayler and John Mannie went out to sea in an attempt to get a line across to some grief-stricken ships, but they drowned in the attempt.

By the time the storm abated on the Tuesday there were some 38 people known to have died and about 300 rescued. From that day funerals became a daily occurrence as more bodies were washed ashore. The victims were buried in Port Elizabeth’s South End Cemetery, where there is also a monument recalling the tragedy. The monument has the names of all ships recorded plus the names of victims identified and the names of the local men who made the rescue attempt (click here to read Firefly article, 2011).

For a more detailed read on the topic see web articles by McCleland (2017) and McGregor (2011).

4) Wrecked ships photographed

As day dawned on Monday 1 September 1902, a scene of absolute chaos was revealed. The whole beach was covered with shattered timber, beached vessels and sodden cargo.

Following the foul weather, the Horwich Brothers, who had a studio at 122 Main street in Port Elizabeth at the time, did not waste any time and along with a number of other photographers recorded the resultant chaos over a number of days.

There will no doubt be more photographs produced of the event by the two brothers.

4.1) Photograph 1 – Ship details

- Iris - British built Norwegian transport sailing ship of 552 ton. Build during 1863 – Captained by O. Berthelsen;

- Oakworth - A Scottish built, British owned cargo sailing vessel of 1242 ton build during 1874 The ship was on route from Port Pirie carrying with a 600-ton cargo of grain. Captained by J. Davies;

- Emmanuel - Dutch build, German owned transport sailing ship. This iron barque of 1201 tons was built during 1876/77 as the full rigger Kinderdijk. During 1888/89 the ship was lengthened and reduced to a barque (now 1147 tons). She was employed mainly in the Indonesian trade until 1898 when she was sold to a German shipowner and renamed Emmanuel. At the time of the catastrophe, she was under the command of Captain Tuitzer, also seemingly on route from Port Pirie with a cargo of grain;

- Content – Swedish built (1891) and Norwegian owned sailing barque of 547 ton under the command of Captain Gustafsen. She was on route from Rangoon with a cargo of rice when she was wrecked during the Port Elizabeth gale.

The Iris, Oakworth, Emmanuel and Content shipping vessels stranded on the Port Elizabeth beach following the devastating Great Gale of 1902. At least another two beached vessels, which were not recorded on the photograph by the photographers, can be seen in the background. The ship in the far distance (right of image) is suggested to be the ship Constant which can be seen on the photograph below. Photograph captured by the Horwich Brothers who would have captured the names of the vessels on the original glass negative before producing the paper printed photograph. The photograph is mounted on a 25,3 x 30,5cm display cardboard.

4.2) Photograph 2 – Ship details

- Arnold - French built German iron transport sailing ship of 854 tons built during 1863. The ship was under the command of either Captain Ahlars or B. Haverkamp at the time. She was transporting railway sleepers;

- Constant - Norwegian built transport sailing ship of 292 ton built during 1886. The ship was under the command of Captain Jacobsen when on route from Rio de Janeiro with a cargo of coffee.

The Arnold and Constant shipping vessels stranded on the Port Elizabeth beach following the devastating Great Gale of 1902. The event attracted many onlookers for a number of days. Photograph captured by the Horwich Brothers. The photograph is mounted on a 25,3 x 30,5cm display cardboard.

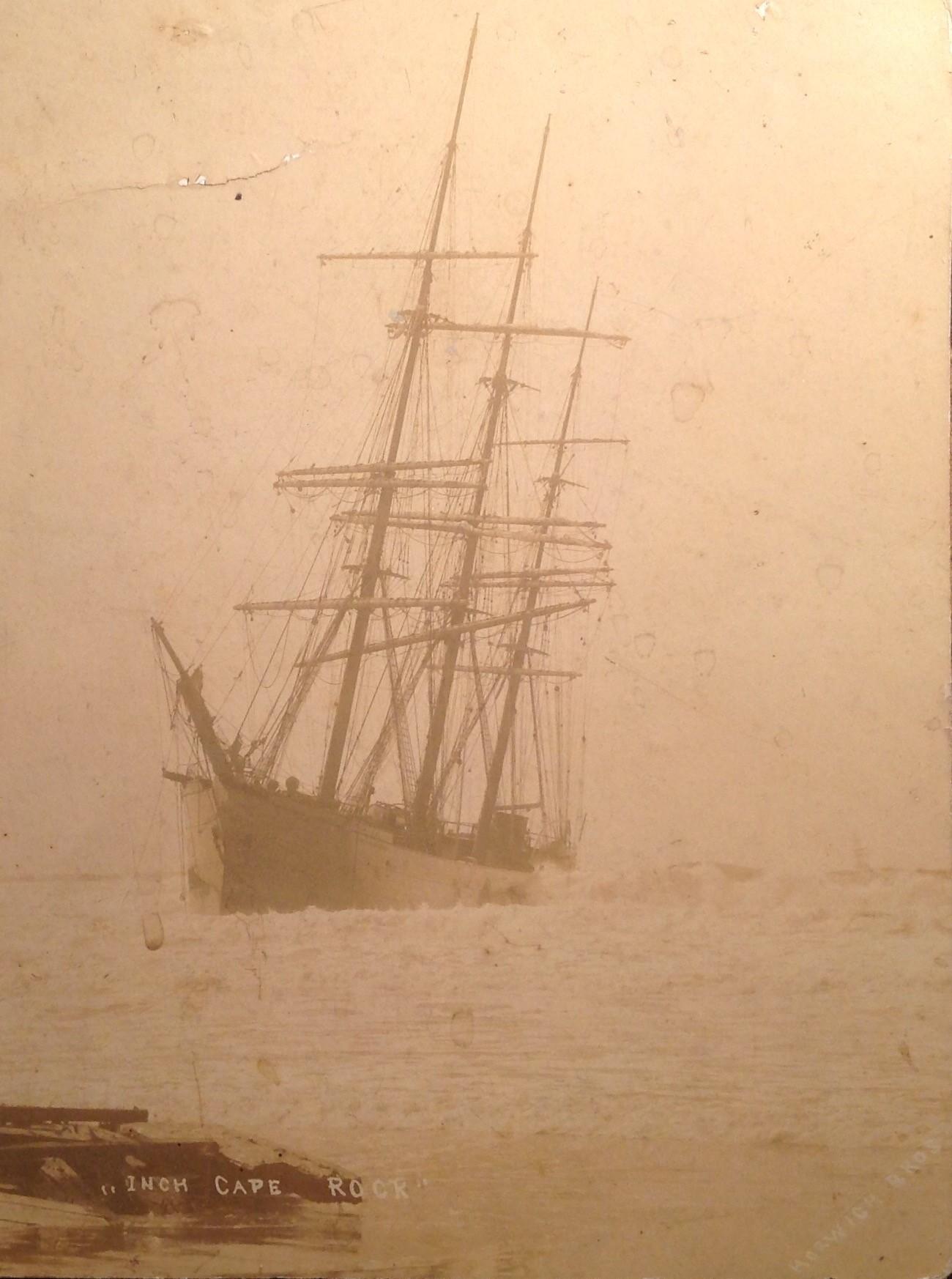

4.3) Photograph 3 – Ship details

- Inchcape Rock – A British full-rigged ship which was built in Scotland during 1886. Named after the Inchcape Rock lighthouse, the world’s oldest surviving sea-washed lighthouse, which lies 11 miles off Arbroath. The vessel was under the command of Captain Ferguson when on route from Portland, Oregon.

Inchcape Rock named after the Inchcape Rock lighthouse photographed by the Horwich Brothers shortly after the Great Gale of 1902. Image is mounted on a 17,5 x 21,5 piece of cardboard.

This photograph was probably taken a week or so after the storm. Here shattered timber can be seen strewn over a long stretch on the beach. In the background people can be seen on some of the remainders of the shipwrecks still in the water. In the far distance more ship wrecks can be seen. The number of people on the beach, assumed to be mainly curious onlookers, confirms the social impact of the event. The photograph is mounted on a 25,3 x 30,5cm display cardboard.

A number of other photographers also photographed the scene, but it seems that the Horwich duo focussed on putting together a detailed portfolio of images.

Also see additional images of the disaster by other photographers on the DRISA website (click here to view) and www.wrecksite.eu. The images on the DRISA website seem to have been produced by a photographer in the employ of the South African Railways Publicity department.

5) The photographers – Horwich Brothers

The parents of Morris and Alexander Horwich have been recorded as Russian born. Their mother was a Pearlman. The youngest of the two brothers, Alexander, was also born in Russia.

The exact date of arrival of the two brothers in South Africa still needs to be determined. Indications are that the arrived during 1899, with the intent of photographing the Anglo-Boer war.

It seems the brothers remained in South Africa for a period of only some 8 years (until 1907) during which period they were also active in Beira (Mozambique) - The South African National Archives holds two of their images captured there (in the Jeffries Collection).

Other than their photographic work, the two brothers hardly left any footprints in South Africa in that there is no archival information available on them, resulting in the information on their South African stint being sparse.

Photographs produced by the two brothers confirm that after the Anglo-Boer war they were active in the Transvaal (both Lydenburg and Belfast). It is assumed that they gave up their studio in Port Elizabeth (122 Main street) after the war. Although Cabinet Card format photographs exists of their studio work, these are not common, suggesting that their main focus was not on studio work whilst based in the Transvaal.

Whilst there is gap as to their whereabouts following their departure from South Africa, it can be confirmed that the brothers finally emigrating to the USA during 1909 where they managed a studio for many years. Their studio, which they named the Postal Studio, was based on Broadway in San Francisco.

Whilst records indicate that a number of individuals with the surname Horwich originated from Russia (and were therefore in all probability Russian Jews), the surname is actually an English surname, meaning: “Belonging to Horwich or alternative being a dweller at the muddy or grey place”.

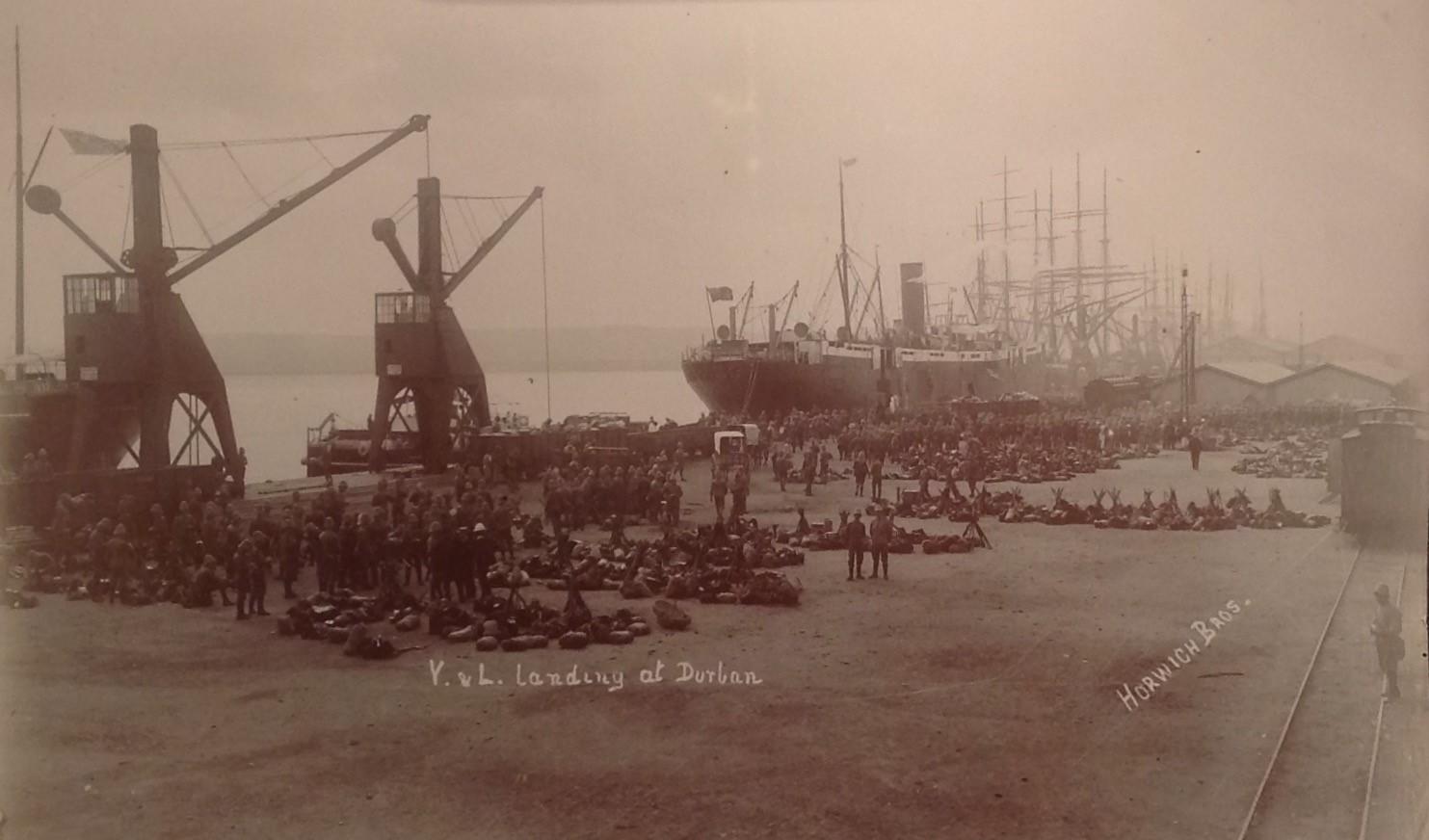

An Anglo-Boer war photograph taken at the Durban Harbour. The Horwich Brothers have produced a significant number of Anglo-Boer images. Ongoing research will need to confirm where exactly the brothers were active during the war. It is suggested that it was the Anglo-Boer war that brough the Horwich Brothers to South Africa in the first place and that the images of maritime catastrophe above were opportune event for the brothers.

5.1) Morris Jack Horwich (1874 – 1953)

Morris was born on 22 January 1874 in Wales, England and died aged 79 on 4 February 1953.

He would have been 28 years-old when photographing the Port Elizabeth maritime disaster.

A shipping register from 1907 indicates that a M. Horwich left the Cape Town Harbour for South Hampton. The inscription further suggests that this Horwich was a 40-year-old teacher from Transvaal. Our Morris would have been 43 during 1907. This in all probability therefore is one and the same person. The fact that his profession is recorded as a teacher is an interesting addition. This may confirm that the brothers discontinued their photographic establishment around 1905 whilst based in Lydenburg. Morris then seems to have entered the teaching profession for a period of two years prior to departing South Africa.

It is not clear where Morris resided between 1907 and 1909 but he eventually emigrated to America during May 1909 – 5 months prior to his brother arriving there. Morris entered America from Canada. There is a remote possibility that he was attempting to set up a studio in Canada after leaving South Africa.

The 1930 USA census indicates that Morris got married for the first time at the age of 44. Limited details are available of his brief marriage to Blanche Horwich who was born on 26 November 1888. Their marriage did not last long in that a subsequent census (1940) indicates that Morris, aged 64, was divorced. The same census has him recorded as a Photo Novelty salesman.

The South African archives does hold a naturalisation file of another Morris Horwich, recorded as a Russian born Jew who was a merchant in Rhodesia between 1889 and 1904 – therefore not our photographer Morris.

Cabinet Card format studio photograph of an unknown sitter taken in a Belfast (Mpumalanga) by the Horwich Brothers. Studio images produced by the Horwich Brothers are minimal, suggesting that they never settled for long in any town or confirming that studio work was not their preferred way of applying their skills. The brother did however later set up a studio in San Francisco.

5.2) Alexander Horwich (1879 – 1941)

Five years junior to Morris, Alexander was born on 10 April 1879 in Minsk (Russia) and died aged 62 on 17 July 1941 in California.

Alexander (or Alex) would have been 23 years old when photographing the Port Elizabeth maritime disaster.

The brothers were clearly restless in that records indicate that Alex visited America during 1905 and finally emigrates there on 31 October 1909 settling in San Francisco. It is not known whether he returned to South Africa following his initial 1905 trip to America.

Alex was 43 when he married for the first time. He married 27-year-old Russian born Bessie Becker-Goldstein-Horwitz (born 2 August 1882) on 15 November 1921 in San Francisco. Bessie emigrated to the USA aged 11 with her parents during August 1893. The Horwich couple had one daughter, Helene, who was born during June 1926. Bessie also had a son Samuel Goldstein, born 1916 (Stepson to Alexander). Bessie is also recorded as having been a photographer.

Bessie applied for American naturalisation during December 1942, but this was declined due to her “failure to establish a good moral character”. Naturalisation was eventually granted to her during 1947.

6) 15 years later - another Algoa Bay maritime disaster photographed (1917)

Another fascinating image is that by the photographer VR Pigott, taken on board the sailing vessel “Colonial Empire”.

Pigott actually got onto the already abandoned sailing vessel whilst it was being flooded by sea water.

The Colonial Empire was a fine four-mast barque, the last of George Duncan's Empires, built by Reid & Co. during 1902. The ship was described as a fast-sailing vessel, in that on her maiden voyage she sailed from Cardiff to Mauritius in 79 days.

The Colonial Empire came to grief on Thunderbolt Reef, Algoa Bay on 27 September 1917. Captained by JA Sanders at the time, she was carrying kerosene and oil for her last owners, the Anglo-American Oil Company.

The Norwich Bulletin of 20 October 1917 reported that:

…the 2436-ton bark Colonial Empire from New York, with a cargo of paraffin in cases, has gone ashore on Cape Recife, near port Elizabeth, and became a total wreck. The crew were saved, and the cargo is being salved.

In a follow-up article, The Norwich Bulletin on 31 October 2017 reported that:

…the master of the barque Colonial Empire was found blameworthy at the time, but the Court of Inquiry, taking into consideration his long service and clean record, and the fact that he was towards the close of his seafaring life still at his post, notwithstanding the present dangers of the sea, suspended his certificate for only three months.

The sailing vessel Colonial Empire photographed by VR Pigott after its demise in Port Elizabeth during 1917. This is an exceptional photograph in that the photographer found a way into the vessel in its watery grave. It is suggested that Pigott would have produced more photographs of the stricken vessel. Item is mounted on a 17 x 22,5cm display cardboard.

Closing

Back to the Great Gale of 1902.

This event in all probability may have been the first natural disaster to have been photographically documented in South Africa. This still needs to be confirmed.

Ongoing research is also required around the Horwich brothers in terms of:

- Identifying the number of great gale images produced by them;

- Their movements in South Africa (especially after the Anglo-Boer war);

- Identifying the number Anglo-Boer war images captured by them. This may become an article in itself.

Be on the look-out for a future article reflecting on other catastrophes photographed in South Africa prior to 1920.

Special acknowledgements:

- Dr. Marcel Safier – a fellow photo historian from Australia - for providing the author with some important leads on the Horwich Brothers

- Paul Cheifitz – Historical researcher – for providing 1907 passenger list containing Morris Horwich details

- Johannes Haarhoff – for providing a link to the DRISA website that contain additional images on the 1902 disaster.

About the author: Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources:

- Firefly (2011). 1902 Great Gale memorial (portelizabethdailyphoto.blogspot.com)

- Grobler, R. (1996). A Framework for modelling losses arising from natural catastrophes in South Africa (repository.up.ac.za)

- Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection

- Horwich meaning (www.forebears.io/surnames)

- McCleland, D. (2017). Great Gale 1902. Port Elizabeth Yore (thecasualobserver.co.za)

- McGregor, Z.A. (2011). Port Elizabeth’s “Great Gale” of 1902 (globalbuzz-SA.com)

- Port Elizabeth history – extracted September 2021 (Britannica.com)

- Redgrave, J.J. (1947). Port Elizabeth – In bygone days. Rustica Press. Wynberg

- Unknown (2020). Worst Natural Disasters in South Africa (briefly.co.za)

- Urquhart, C. (2007). Algoa Bay in the Age of Sail (1488 – 1917) – A maritime story. Bluecliff

- Wreck site – Website from where information was extracted around each of the ships affected (www.wrecksite.eu)

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.