Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

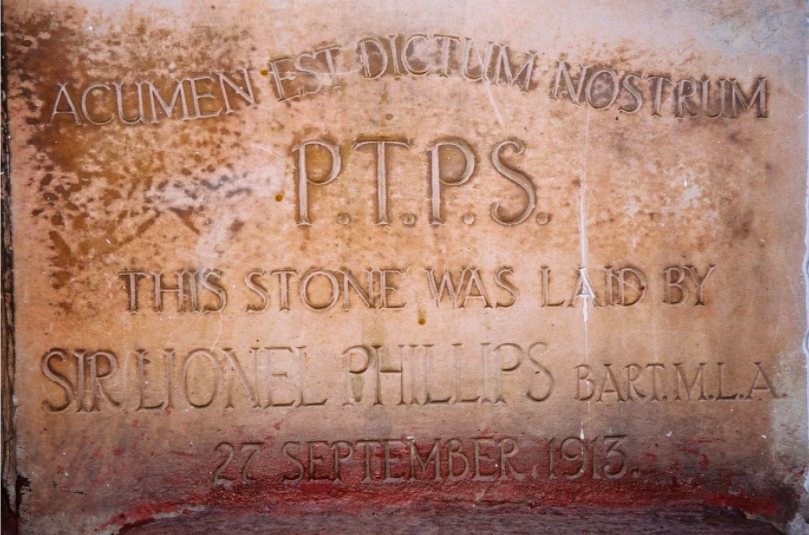

It was always known just as ‘PTPS’ which stood for the words seldom spoken, saving people the trouble of the mouthful of ‘Parktown Preparatory School’. I arrived in 1946 aged eight. The foundation stone by the front door said ‘Acumen Est Dictum Nostrum’. None of us boys knew what that meant. The stone was laid by someone called Sir Lionel Phillips in 1913. None of us knew who he was. As a Roman writer observed ‘the times are bad and this is an ignorant generation’. We may have been ignorant but there was an expectation that after a period of immersion at PTPS we might come to know things. ‘Acumen’ might be a bridge of knowledge too far, but we would at least know some things. But what was a ‘Bart’, and what did ‘MLA’ mean?

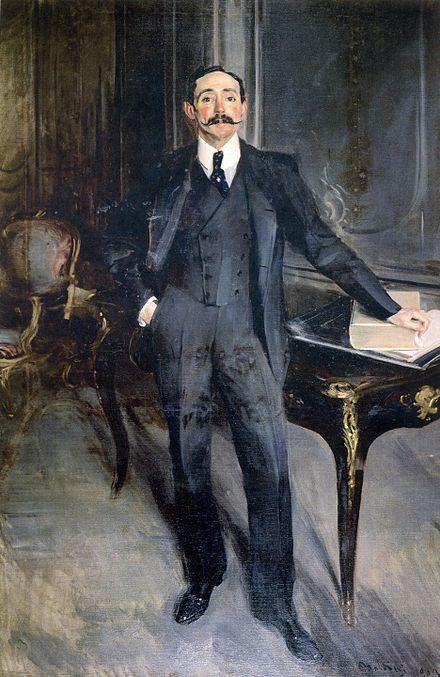

Portrait of Lionel Phillips (Wikipedia)

My father, an engineer in the Johannesburg Municipality, had gone away to the War and not returned to us in Linden extension where, to my mother’s annoyance, we were governed by the Peri-Urban Areas Board in distant Pretoria. She nurtured other annoyances, among them my father becoming a Sapper and getting no further than the Cape where he met an English woman displaced from Egypt when Rommel swept across the western desert. In saving the world for democracy he had simultaneously discovered his own freedom from family life with my mother and me. He never did return to us. My mother was not best pleased. When the fathers of other boys did not come back from the War it was because they were ‘killed in action’. Everyone seemed very proud of fathers, husbands, brothers, killed in action. My father’s war took him no further than to the Cape and my future stepmother.

My mother would frequently lament, ‘the men had a good War’. Her school motto, of Roedean in Johannesburg, Honneur Aulx Dinges, ‘Honour to the Worthy’, imposed high expectations of human behaviour. Clearly, she had signed up to a marriage to a man whose conduct fell far short of these ideals. The husband she had chosen on a quiet night at the Country Club was the cause of her social humiliation rather than a source of pride. She had found him a good talker with a nice sense of humour. Now that she no longer had cause to laugh, she would see to it that he became the source of a monthly stipend for her and their boy, me. Her only other consolations were her memories of schooldays, her beloved father ‘AB’ who had been a famous cricketer who died when she was twelve, and the Luger pistol my father left in her possession when he left us for the War, and not much else besides.

Old postcard of Roedean

I did not appear in her list of consolations. Our life in what she called ‘the back of beyond’ was almost totally devoid of other children and I was shy and wanting in talking skills. I imagine I was now what is now described as ‘beyond parental control’, already a defiant young rebel with a cause, fighting tenaciously against her continuing attempts to discipline a squirming boy intent on protecting his backside. I was clearly in urgent need of ‘a man’s hand’, the control that would have been exercised by my father if it were not for the War and ‘the other woman’. Something would have to be done about me. But what? The answer was a boarding school, a prep school, enter PTPS. As she explained it to me, I was going somewhere nice to have fun with other boys. It sounded like a good deal.

I was eight when I arrived at the school in 1946, nine when I left.

3 Trematon Place, once the home of PTPS (Bernard Hall)

Viewed from the outside PTPS had hardly changed when I took this photograph some thirty years after my time there. Behind the downstairs window on the far left was the dining room. The window to the left of the front door shed light on the dreary room where Mr Hadland, the Headmaster, dispensed justice, my mother’s missing ‘man’s hand’, except of course that it was not his ‘hand’. The Hadland’s home, Mr and Mrs and their son John, occupied the downstairs area to the right of the front door. The kitchen lay behind their quarters with a door and window to the rear.

Upstairs, the window on the left was ‘my’ dormitory. Another dormitory, and I forget now whether it was more than one other dormitory, led off a corridor running down the centre of the upstairs as far as Matron’s quarters facing to the front on the right-hand side in the photograph. At the left-hand end of the corridor a door led to an iron staircase which was our route in and out, the front door was barred to boys except with a parent or parents on arrival.

The little room behind the window above the front door was a sort of locker room and across the corridor was the bathroom with two baths and adjacent toilet. At bath time we would queue and take turns to be washed down by Matron or one of the African women who helped here as well as with kitchen duties. No doubt they did cleaning and bed-making as well, we boys did not even make our own beds.

I remember Matron as Miss Spiring, sometimes known sotto voce as ‘Spyring’. Or have I imagined that? Was she a Miss or Mrs? How old was she? Did she have any family? I knew not then but wonder now. It must have been a demanding job, dormitory and dining duties and the care, clothing and cleanliness of a gaggle of small boys. Long hours and little pay? I remember now the moments when splashes of humour or kindness broke through the surface of her stern carapace and voice.

The dormitory was always kept clean and tidy by the African women who worked under instruction from Matron and Mrs Hadland. A wooden floor. Iron beds down each side of the room. The bedding was thin and not equal to winter nights. Washstands, each with a bowl and jug of water, ready for our face wash and teeth cleaning come the morning, stood at the windows end of the room. I smile now when I see such stands, bowls and jugs, in up-market household emporiums.

Trematon is a place in Cornwall and like, Margate, Southport, Ramsgate, and other South African place names at the time, was a reminder of what my South African born mother regarded as ‘home’. The man-eating lions of Trematon Place, Johannesburg, are amongst my earliest memories. On my first lonely, homesick, terrified night in the dormitory I heard a loud roaring sound which seemed very close. Noticing me in an agitated state the boy in the next bed made efforts to reassure me, ‘It’s only feeding time for the lions in the zoo.’ A second boy chimed in, ‘Ja man, they sometimes escape, that is how there was an empty bed for you when you came here. Taken in the night he was. We found his bones outside the classroom next morning.’ Reassured in this way, I slept very little that night.

Trematon House with blue plaque (The Heritage Portal)

A few weeks later I was beginning to relax and learn the names of the other boys, some of whom were playing with marbles on their beds. Someone loaned me a few marbles just as Matron appeared scowling in the doorway. ‘Marbles on the beds,’ she snapped before collecting them up from us. ‘Confiscated’. Next morning at breakfast Mr Hadland, the Headmaster, always formally attired in a somewhat tired suit, made a Dickensian speech about the dreadful behaviour in the junior dormitory the previous evening. Those concerned were to see him after breakfast. The boy next to me said, ‘Cuts’. What’s that, I asked. ‘You’ll soon see,’ he said. Which I did when we all trooped along the corridor and jostled in a queue to wait our turns to enter Mr Hadland’s office. Nobody seemed keen to go in first. Then, as each boy went in, there were sounds like repeated rifle shots. Did Mr Hadland shoot boys who played with marbles in the dormitory? Was that what my mother hoped for? I was relieved to see boys emerge still alive, rubbing their bottoms. I was last in and surprised when Mr Hadland told me to touch my toes. Why? I soon found out. It hurt a lot but I survived. After we had all had cuts, I followed the other boys as they ran through the dining room, down the step, and along to the outdoor boys’ toilets at the edge of the site. Then they all pulled down their shorts to compare the stripes on their buttocks. Although still very shy and nervous amongst other boys, I felt bound to pull mine down too. We were now brothers in arms. Finally, I watched, feeling wholly inadequate as the other boys urinated up the wall to see who could achieve the greatest height. My own pathetic dribble just trickled down my thighs. Boys will be boys! Yes, disgusting. Or, as my mother, always eager to show off her Roedean French would have said, ‘dégoutant’.

Visits to see Mr Hadland were not a frequent or particularly severe occurrence and, looking back, generally fair and, in the way of the times, what we deserved in view of our misdemeanours, certainly punishments our parents endorsed. A few boys prayed beside their beds at night. I very quickly discovered that praying, ‘please God may I not get the cane tomorrow’, was totally ineffective as a guarantee of a pain free existence. My prayers gradually diminished in frequency till they no longer burdened the in-tray of the good Lord above.

Another dormitory memory which survives occurred on the evening of the fifth of November when a buzz went round the dorm after one boy noticed a firework display in the front garden of the big house opposite. The posh family watched as rockets screeched up high into the sky, Catherine wheels trundled around spewing flames, Roman Candles cast flickering flames, sparklers fizzed, all freely providing any amount of spectacle for our shared enjoyment. That was, till Matron got wind of it and arrived in bellicose mood, ‘Away from the windows, boys, no one is to look out, that is private.’ And that was that, no free fireworks display for the boys. But, as the windows had no curtains, many an eye continued to glance across the road. The prohibition seemed petty then and, indeed, does now.

From the dormitory across the corridor from us we could see the swimming pool where each and every morning, summer or winter, John Hadland, swam before breakfast. Voluntarily! A remarkable man. We looked at him in total awe, silently doubting his sanity. Mention of the swimming pool reminds me of the day when we were lined up outside the dining room facing the Hadlands with Mrs Hadland, a generally cheerful, smiling lady, announcing that she had been through Mr Hadland’s pockets and found enough money to buy some prizes for a swimming gala to be held in the pool that very day. It was. No use asking me what the prizes were. I came last in everything, narrowly escaping drowning, thus further proof of my lack of sporting prowess.

Which, still upstairs, leaves only the bathroom, host to two baths side by side and an adjacent toilet. At bath time we would queue naked while clutching our towels until our turn came to be soaped and then washed down by either Matron or one of the African women who helped here too. First come meant warm, clean water, last in line the opposite. It was always an opportunity to see from any stripes on bare bottoms which boys had been that day to see Mr Hadland.

In the dining room downstairs we sat on benches beside the long refectory tables, beginning each main meal with someone, most often a boy, saying a Grace beginning with ‘for what we are about to receive’. The African women servants brought food out from the kitchen and, looking back, were responsible for many of the vital tasks involved in this aspect of school life.

Supper time came after bath time so we were by then wearing our pyjamas and dressing gowns. In my time two atypical ‘dishes’ caused us much merriment, dry biscuits from which weevils emerged one morning at breakfast. Attempts to set away weevil races from one side of the table to the other were rapidly curtailed and the evidence removed. Another time the boiled eggs for breakfast contained perfectly if not completely formed chicks. They too were removed in haste.

A boy’s birthday was marked by flickering candles denoting age on a cake, presumably ordered by a doting parent, accompanied by a wailing rendition of ‘Happy Birthday’.

I cannot remember any dishes of which we sang loud praises. I am sure though that we were well fed and I can recall no incidents in which boys were sent home or to hospital with food poisoning or malnutrition.

There were other hazards from which no boy was immune. Although no one in my time was eaten by one of the man-eating lions of Trematon Place, splinters were a constant hazard for if they worked below your skin, they often travelled all the way to your heart then – curtains. Snakes, insect bites and lightning could all ring the exit bell.

Sadly, however, we did suffer one fatality, that of a boy shot accidentally by his brother in the school holidays. After breakfast, the ever lugubrious Mr Hadland, wearing his gloomiest face, announced this sombre fact adding only that one of our own had died in an accident when his brother emerged from the scrub with a loaded rifle which caught on a branch and went off BANG. We were told to sit on the grass somewhere and say a prayer for the deceased or, as one of my pals whispered, ‘What prayer do you say for someone diseased’.

Still on the same side of the road was a small cottage which, I believe, was used as accommodation by university students, perhaps in exchange for supervising Prep and boarding duties.

More importantly the cupboard storing one’s tuck was located in the porch of the cottage. It was only be opened at a set time each day by a member of staff with a key. Unless, that is, there was a budding locksmith amongst us, or someone willing to break open the lock with a piece of metal found lying around. So, some tuck was stolen while fearing retribution of the worst kind. Or perhaps the perpetrators might get away with it scot-free. I should know, one way or the other. My secret, I am sure, is safe with the reader.

Were there any day boys? I remember not.

I do remember the first school holidays when, to my surprise, my mother arrived in the Austin 7 and told me we were going to stay at a guest farm in a place called Magaliesberg. Apparently, our house at Linden extension was ‘up for sale’, our possessions going ‘into storage’. What was going on, I wondered. I liked the guest farm. It was beside a lake and people from Johannesburg came at the weekend to look at the birds. There were other guests but no sign of anyone farming.

Back at school my attention returned to the business of learning. The business part of the educational operation took place in the classrooms across the road. This was a purpose-built structure built to last. I remember two classrooms interlinked by a folding door between the two rooms. Looking back, I cannot praise our class teacher highly enough, a young woman who was patient, kind and able to exercise control through her personality alone. For the first time I learned to read, write, spell, do sums, and generally settle in an ordered environment in which my progress as a learning person could take root. The schoolbooks, I remember as published by Blackies in Edinburgh, and seemed old and, with my wisdom of age, I am sure they were old. Even when I was at PTPS it must be said that rods, poles and perches, and all the other strange measures recorded on the backs of our exercise books, were no longer in common usage. And no mention of ‘morgen’.

Facing the classrooms was a long-disused tennis court, its wire netting surround long since rusted and rotted away. This was used on an occasion I remember when we spent a day rehearsing a calisthenic routine which we performed for the parents who arrived to watch the following day. In later years when I saw newsreels of regimented gymnastics in repressive states, I paused to wonder what our little display had been about, educationally speaking.

Further down the site was a red-oxide painted corrugated iron shed containing ‘the library’ which consisted of shelves of dusty and heat-worn books which, to my knowledge, no boy ever borrowed. I think it is no exaggeration to say that no boy ever entered the library except for the boy who enjoyed the ephemeral status of ‘librarian’, part-time and unpaid of course. It was a role I aspired to but never achieved, my first but not my last big disappointment.

Walking back towards the road was another red-oxide shed, larger and used as a gym. Under this heading I remember only boxing, which I hated because being very short-sighted I was a free hit with my glasses off. I disliked wrestling less but in truth I was not suited to any of the violent arts. The instructors, as I remember them, were men who might have been old enough to remember The Ring at Étaples in northern France, a notorious training ground of the British Army in the First World War. It was as though we were being prepared for a rerun to that kind of war, forgetting only that the art and science of war had changed more than somewhat during the by then recent Second World War. Perhaps it was too much to hope that we might be trained in tanks that would allow us to demolish Mr Hadland’s study.

Walking further between the classroom block and the gym, tennis court and library, led one across the quiet road surrounding the oval, an area of grass which we used occasionally for cricket or football. There was no regular sport, no coaching and only inferior equipment. I remember that the school appeared to own only one cricket bat, too heavy by far for a boy my age, now nine. I remarked on this to Mr Hadland who snapped back, ‘a bad workman blames his tools’. True I suppose, though a good workman with good tools may be better equipped in life.

On Saturday morning we sat in our classroom to write letters home. As my parents were no longer together, I wrote to my mother one week and my father the next week. We could say very little of consequence as all letters had to be read by Mr Hadland before they were posted so mention of things like the weevils and the half-formed chickens was strictly verboten. Letters home were now rather confusing as my father, who had reappeared on the scene in a walk-on part, collected me every Sunday after church with me spending one Sunday with him and being dropped off at and collected from my mother the following week.

Church was a very formal occasion. On Sundays we formed a line outside the dining-room and after a thorough inspection of our hands, nails and behind our ears (cleanliness), shoes (polished), tie and cap (straight and correct angle), blazer (buttoned) we were escorted in a crocodile clutching the half-crowns we had been handed before setting off to St George’s Anglican church. On the opposite pavement a crocodile of girls mirrored our progress. I never did, and still don’t, know which school these girls attended, or where. After the interminable service, the hymns, readings and sermon, our half-a-crown handed in for the collection it was off for the day with a parent or parents depending on the marital states concerned.

1947 saw the Royal Visit to South Africa. When the Royal visitors reached Johannesburg, we were prepared in an even more perfected form than for church on Sundays before being ferried to stand on a pavement on the Royal route to watch as the motorcade flashed by. There are a lot of roads in South Africa and blanket coverage of cheering subjects proved an ambition too far. I remember a long wait, a sparse group of people, and a fleeting glimpse of people, perhaps a King and Queen and two Royal princesses amongst them as they disappeared in a cloud of dust. My uncle Percy Auret, a lawyer in the firm Auret and Wimble, had his office overlooking the front of the City Hall. From there a few days later I had a better view of the Royal family when, after another long wait, they emerged on to the forecourt for a display of girls dancing to the sound of the singing of ‘underneath the spreading chestnut tree’ which was said to be one of the King’s favourite tunes.

An old photo of Johannesburg City Hall

When my mother and I returned to the guest farm in the school holidays some months later she announced that in future we were going to live there. It was going to become a school for which she would be working as the gardener. My days at PTPS were numbered and a few weeks later we boarded the train at the Park Station and chuffed our way to Magaliesberg where we were met by the headmaster of the new school. He had come by flying boat from England and was called Mr Gorton. His sister performed the matronly duties and her daughter, Prudence, a girl my age, was a fellow pupil.

Old photo of Park Station (Johannesburg Heritage Foundation)

Mr Gorton, or ‘Naughty Gorty’ as my mother later referred to him, drove us down the dusty road till we came to the sign no longer announcing ‘Mountain Lodge Guest Farm’ for the words ‘Guest Farm’ had been over-painted by ‘School’ so it now read ‘Mountain Lodge School’. Mr Gorton proved to be a very different sort of Headmaster.

Farewell to PTPS!

PS - What was the Mountain Lodge Guest Farm before it became the Mountain Lodge School is now the Mountain Lodge Psychiatric Centre run by the Salvation Army to provide residential psychiatric care for sixty men and women.

Some years ago I found the image below and accompanying text by ‘SmugMug’ on the internet. I would love to have discovered the person who put it there, if only to acknowledge the source. The only clue is the attached phrase ‘cjmh family’:

The final school photo of PPS (sic), Johannesburg, taken on 12 December 1957 before its closure at the end of that year. I am seated fourth from the left. The adults pictured were (l to r) Mrs Menzies, Mrs Ross (both excellent teachers), Mrs Hadland (wife of the headmaster), Mrs Pargiter (my first-year teacher to whom I owe a great deal), next to Mrs Pargiter is the Hadland’s son, John Hadland.

The final photograph. The classrooms are in the background. The remains of the tennis court were behind the photographer.

This photograph, taken ten years after I left PTPS, left me wondering. Where was Mr Hadland? Why did the school close? The writer must be younger than me so still alive? And anyone else there in 1946-7? Hands up?

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.