Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

During the reign of Queen Victoria the then British Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli once told the House of Commons, ‘More men have been knocked off balance by gold than by love” but to be fair to the man he also said on another occasion “We are all born for love. It is the principle of existence, and its only end”.

Gold has always had a fascination for humankind and golden artefacts have been discovered across the globe, on every continent, from the ancient civilisations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, China and Central America (the Mayan people). There was no interaction between these civilisations (except perhaps the first two mentioned) but they all had one thing in common in that their craftsmen worked to make ornate jewellery with a yellow metal that we know as Gold (Au).

The question to be asked then is, why was gold held in such high regard by them and considered nobler than any other metal element found in the earth’s crust? Well the hit song by Spandau Ballet “Gold” (sung by Tony Hadley, in 1983) said it all in one line “You’re indestructible!” Gold does not tarnish or rust (like iron) and does not react with acids, except for Aqua Regia (a mixture of nitric and hydrochloric acids in the ratio 1:3).

Gold was to be found as alluvial deposits in the streams of the foothills of mountains and because it was yellow, bright and shiny it was easily detected. When gold was found to be easy to melt and malleable, uses for this pleasing to the eye metal were many and demand was always going to be greater than its supply.

Until the voyages of discovery by the Spanish and Portuguese in the 15th and 16th centuries the peoples of the eastern and western hemispheres were unaware of the other’s existence, only where there was a land passage such as the Silk Road between China, Asia Minor and Europe did trade and exchange of ideas occur between different cultures.

The Spaniards when conquering the Americas were especially driven by the stories told of a place called “El Dorado” where gold was to be found in abundance. Was it in Mexico? Was it in Venezuela? Was it in Columbia? It proved to be a fable but its promise did not stop the “Conquistadors” risking life and limb in search of it.

It would be their Iberian cousins and competitors - the Portuguese, who would spark a gold rush when they went in search of gold, in their own colony of Brazil. In the year of 1693 bands of adventurers (Bandeirantes) fanned out westwards and northwards from Rio de Janeiro to explore the rugged mountain ranges of what later became the province of Minas Gerais. One group were lucky to find gold (in the vicinity of Ouro Preto, 513 km north of Rio) and its discovery caused such a frenzy back in Rio and Sao Paulo that by 1697 many of their citizens had left in search of their fortune, along with many new arrivals from the mother country. Such was the rush to Brazil that Lisbon had to legislate against Portuguese citizens emigrating en masse! The gold was mainly found in the beds and banks of the many streams (i.e. alluvial deposits) flowing down from the mountains and its extraction was labour intensive but “low tech” with only a shovel, pan and sluice box required. Slaves in their tens of thousands, both indigenous and African, were employed for the heavy manual work and the goldfields lasted for the duration of the 18th century, with gold output peaking in 1750, but as with all non-renewable resources the gold eventually began to run out and by 1807 it was all over.

The later Gold Rushes, of the mid to late 19th century have gained a romantic notion over time, but in reality romance was far from the truth as the majority of those who sought their fortunes found nothing but misery and despair. The first gold discovery to capture the imagination of the whole world was when word got out of gold nuggets being found in the Sacramento Valley, California in early 1848. The first to find gold was James Marshall, a carpenter at Sutter’s Mill (Coloma) on the American River and whilst he was inspecting and cleaning out the tailrace of the saw mill he spied, in a bed of mud, pea sized particles that gave off a peculiar dull glitter. He later was to say “I began to think very hard” and the upshot of his thoughts was to gather up the shiny peas and take them to his boss, Johan Sutter. They both agreed it was gold of high purity and swore each other to secrecy but within a week the secret was out and with it any chance of Sutter keeping ownership of his extensive estate, which he called “New Helvetia” (in honour of his Swiss heritage); he was powerless to stop diggers from overrunning his property in search of gold and he was forced off his land (granted him by the Mexicans) and for the rest of his life he sought compensation from the U.S. Congress for his loss.

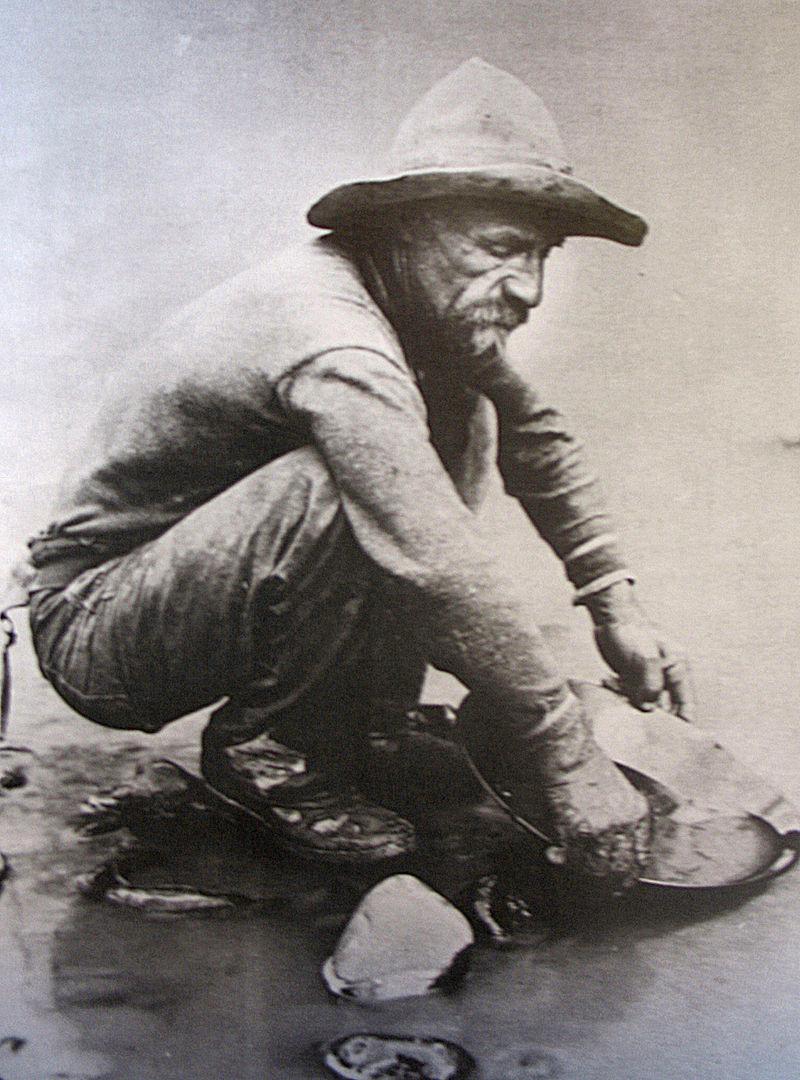

Panning for Gold during the California Gold Rush (via Wikipedia)

In 1848 California was in transition from being a Mexican province to an American territory (as ceded to them in the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo after the Mexican American War) and because of the great influx of fortune seekers it was fast tracked to become the 31st state of the Union on September 9th 1850 (as a non-slave state).

Rumours of fist size gold nuggets that were to be found strewn over the ground just waiting to be snatched up finally reached the world at large and caused a sensation leading to a mass migration to the west coast in the year after the original find. Thus came the Miner 49ers’, with their slogan “California here I come”, those intrepid men and women who faced adversity on the overland trek along the Oregon Trail, from St. Joseph (on the Missouri River) to the Sacramento Valley, California – a journey that with luck and good weather could take three to four months but for many much longer. Gold fever made people risk everything in the hope of making a fortune from the fluvial gold deposits in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada and 50 000 people were prepared to leave the comparative safety of former livelihoods to make a 2 000 mile (3 200 km) trek across the unknown “Wild West”. Unbeknown to them was the hard truth that even before their departure most of the easy pickings had already been taken by those who were on the spot soon after the first gold discovery at Sutter’s Mill, the previous year.

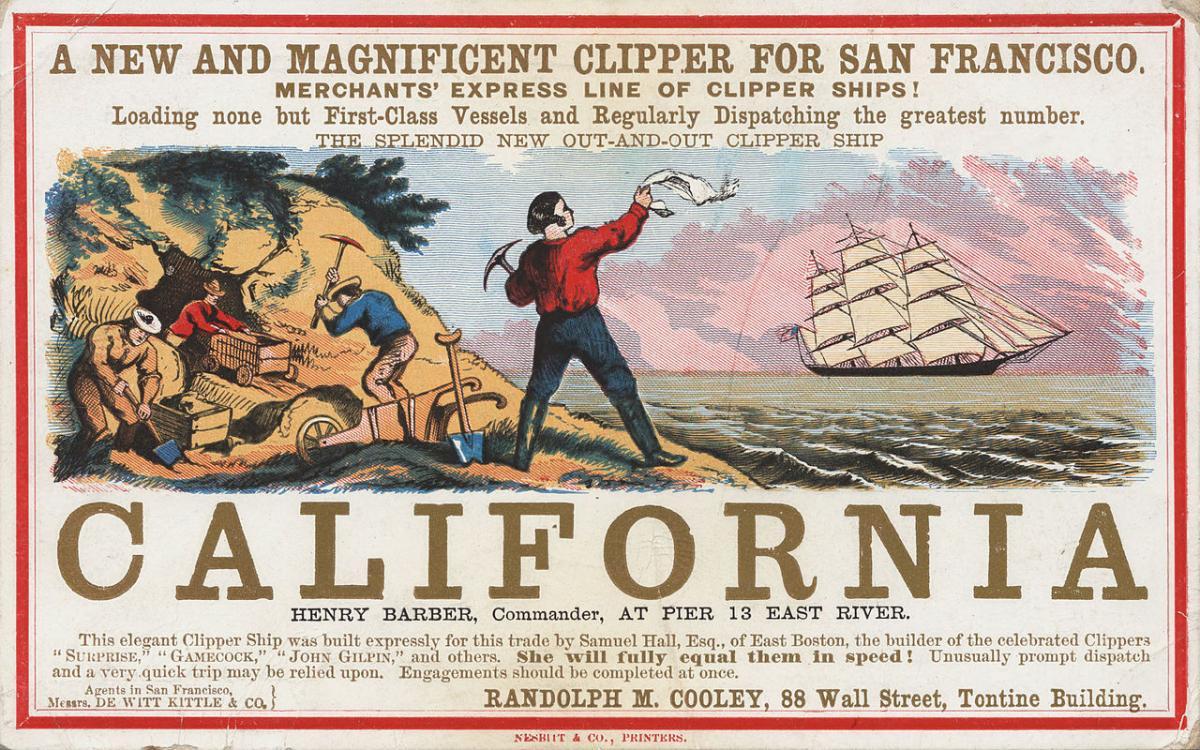

The overland trek was not the only way to reach the Californian gold diggings as a sea passage could be taken by sailing ship from New York to San Francisco around the Horn (the tip of South America) and it was said to be the preferred way to go for politicians, prostitutes and gamblers!

Forty-niner panning for Gold (via Wikipedia)

A young man from the Cape Colony, with wanderlust, by the name of Pieter Jacobus Marais set off from Cape Town on the 31st March 1849 to seek his fortune firstly on the Californian goldfields and after tasting disappointment there he took a chance on the gold rush to Victoria, Australia in 1851. By 1853 he was back in Cape Town without making his fortune but he had experienced life and had become a seasoned gold prospector. Rumours abounded of the possibility of the riches to be found north of the Vaal river and he made up his mind to go northwards on horseback. He reached Potchestroom in September 1853, becoming the Tranvaal’s first official prospector and thereafter he would follow upstream the lesser rivers that were part of the Vaal catchment, the Mooi and Schoonspruit prospecting with spade, pick and pan without much luck. He then continued north towards the distant Magaliesberge where he would on the 7th October 1853 discover specks of gold at the confluence of the Crocodile and Jukskei rivers, the first gold ever panned in the Transvaal. On the 9th October 1853 Marais would travel upstream along the Jukskei and Klein Jukskei (now known as the Braamfonteinspruit) to Zandfontein, the farm of Pieter Nel (now where present day Sandton stands) where he found more alluvial gold in the “Spruit” (close to what is now the William Nicol bridge). A Blue Plaque at the top of Panner’s Lane, Riverclub commemorates his achievement.

Panning for Gold in front of the William Nicol Bridge (The Heritage Portal)

Installing the Panners Lane Blue Plaque (The Heritage Portal)

Blue Plaque (The Heritage Portal)

Poor old Marais, if he had only known that those traces of gold in the Klein Jukskei river (so named for an old broken wagon “yoke key” found abandoned) had been washed down from the top of the hard quartzite Witwatersrand (Ridge of White Waters), he would have found the key to unlock the world’s greatest treasure trove! He was so near yet so far, but his skill set was with spade, pick and pan and he was unable to comprehend the peculiar geology of the region, and those “Banket” outcrops (of the Main Reef), on the farm Langlaagte, just south of the ridge would not have suggested to him that they were gold bearing. He would turn his back on the Witwatersrand and keep on searching for another two years across the length and breadth of the Transvaal without finding a payable goldfield, both to his disappointment and that of the penniless Volksraad.

Marais may not have succeeded in finding payable gold, which would have benefitted the economy of the fledgling South African Republic (a.k.a. Transvaal), but he stimulated interest in others to search for gold in the “Old Transvaal”. He also told the Volksraad what to expect when gold was found; an influx of unruly fortune hunters, to disturb their pastoral way of life.

The world would have to wait another 33 years (until 1886) for the Witwatersrand to unlock its secret and during that time period many would traipse across its barren veldt not knowing there was gold beneath their feet; they did not tarry for long as there was always somewhere better on the far horizon.

The discovery site at George Harrison Park (Gavin Whitfield)

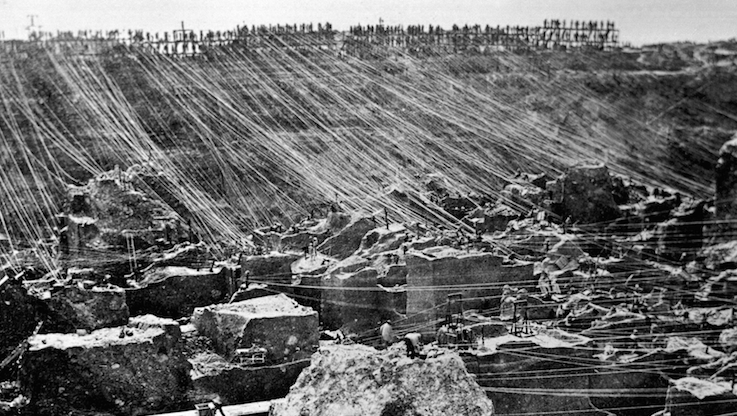

It was therefore providential that diamonds were found in the late 1860s on the western fringes of the Orange Free State - a region to be known later as Griqualand West. The establishment of Kimberley (formerly New Rush) as a centre of mining brought about the wherewithal (both financial and technical) necessary for large scale mining operations that would be carried over to Johannesburg and the “Rand”, when the time came.

Mining Claims Kimberley Big Hole (De Beers Archive)

However the day of the digger was not done and the period between 1870 and 1885 saw the individual prospector staking gold claims in the region of the Eastern Transvaal, from Mac Mac to Pilgrim’s Rest to the De Kaap Valley thence to Barberton. Their participation in extracting the gold lasted up until the alluvial deposits in the beds and banks of the rivers became worked out, from then on spade and pan were of no use and it was a matter for the newly formed mining companies to mine into the hillsides to find the primary source by blasting adits (horizontal tunnels) to win the ore containing the yellow metal before sending it off to the stamp mills for crushing and thence to the refinery for processing into gold bars.

The digger would eventually have to give up his itinerant life of tramping from one goldfield to next ever hoping to strike it rich, as the nature of mining would change to suit the exploitation of the tabular ore body of the Witwatersrand Basin whose northern outcrop (pebbles in a matrix - Banket) was discovered by George Harrison and George Walker one Sunday in February 1886. Hardrock mining would become the norm with the eventual sinking of vertical shafts as the mines went ever deeper. Johannesburg was born and the rest as they say is history.

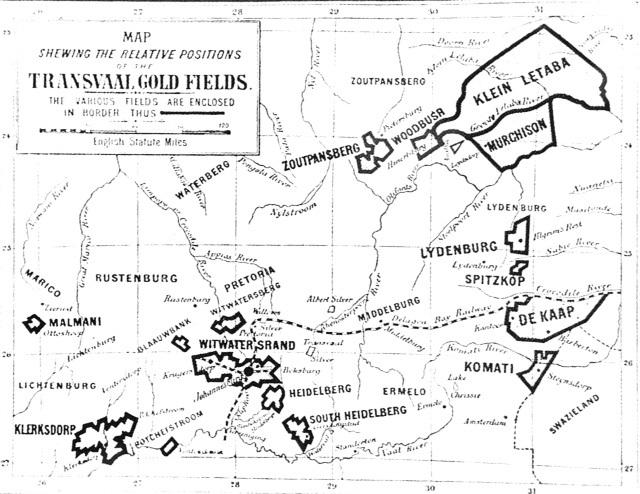

Map of the Transvaal Gold Fields

References and further reading (unless otherwise stated from the Heritage Portal: www.theheritageportal.co.za

- “The Brazilian gold rush” by Jade Davenport, Mining Weekly 12-10-2012.

- “Alistair Cooke’s America” by Alistair Cook, new edition published by Weidenveld & Nicolson, 2002 (first published in 1973 as the companion to the BBC TV series of the same name).

- “Lost Trails of the Transvaal” by T.V. Bulpin, published by Howard Timmins, Cape Town, 1956.

- “Gold! Gold! Gold!” by Eric Rossental, published by Mac Millan, 1970.

- “Guidebook to Sites of Geological and Mining Interest on the Central Witwatersrand” edited by F. Mendelsohn & C.T. Potgieter, the Geological Society of South Africa.

- “Early Settlers and Prospectors in Sandton” by Malcolm Wilson.

- “History of Panner’s Lane, Sandton” by Malcolm Wilson.

- “Panning for Gold in Sandton” by James Ball.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.