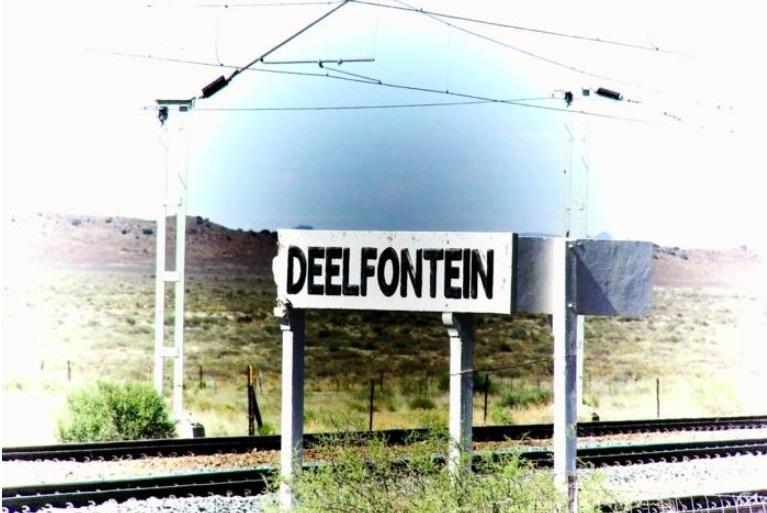

Have you ever been to Deelfontein in the Karoo? It is a small railway siding; back of beyond in the middle of nowhere - a set of parallel rails run into the infinite distance of the vast landscape. It can be reached by car on dusty rural farm roads from Richmond, which lies about 51 kms to the South, about an hour’s drive away allowing for the untarred dirt roads. You realise you have arrived at a place that must have been important a long time ago as you pass through a ruined elaborate gateway that once led to the hotel, with the word “Yeomanry” still visible on the stucco archway. Join the ghosts of people who once sat on the long front stoep and kick a broken brown beer bottle underfoot. Once upon time there was a village, a hospital, a plain close to the railway line was laid out with tortoise tents. For a short time there was a thriving community here served by a store and a hotel. The hotel closed in about 1980. Today, it is a place of desolation, ruins, rank grass, a few wild flowers alongside that lonely railway siding. There is an old cemetery and one moves cautiously over the rocks, abandoned rusty poles and coiled barbed wire. Loose rust coloured clay baked bricks are strewn about and dried bramble branches are obstacles. It is a haunting and haunted place, abandoned and neglected; but there is an echo of romance and nostalgia.

Deelfontein railway Siding (Booktown Richmond)

Abandoned and neglected

The first question that jumps to mind is who were these “Yeomanry” and secondly why was a hospital built here?

The Yeomen of the Karoo, The Story of the Imperial Yeomanry Hospital at Deelfontein by Rose Willis, Arnold van Dyk and J C “Kay” de Villiers is the book with all of the answers. I visited Deelfontein a year ago but it was only when I purchased this book (published in 2016) on this Karoo Hospital and its history that the answers fell into place. Like all good books it raised more questions and set me on a quest, not just to find out about the Yeomen but also to learn a little more about medicine and medical treatment in the Boer War. How did the British with their superior resources treat their wounded? The flip side was what the Boers did with their battle casualties. Why were British losses so high and Boer military losses so low? Did the volunteer Yeomen companies of the Boer war leave an imprint on army organization? How did the lessons learnt (or not learnt) in the Anglo Boer War carry forward into army strategy and response in the First World War? Did experimental medical approaches change how men were treated when wounded in battle? These latter ponder points were not satisfactorily dealt with but as a very detailed book on a specific place in a specific time this monograph makes an important contribution to Anglo Boer War studies.

Book Cover

The authors are well matched to cover the various dimensions of this particular history and remote part of the world. Rose Willis is a specialist historian of the Karoo; Dr Arnold van Dyk, is a widely respected authority on the Anglo-Boer War, who was able to drawn on his vast private library to supply much original documentation; Professor J C (Kay) de Villiers is an eminent Cape Town neuro-surgeon and expert on the medical history of the Anglo-Boer War and on the effects of typhoid. I am now in search of Professor de Villier’s two volume medical history of the Boer War.

The disasters of the Black week of December 1899 was a surprising military setback and led the British military command to realize that they needed more men, more equipment and greater drive to defeat the hardy Boer commandos. The Imperial Yeomanry was the solution; created in January 1900, it was an enterprise that set about recruiting middle class volunteers, men aged 25 to 35, drawn from the upper class in England, Ireland and Scotland who could shoot and ride; they were to be moulded into a mounted infantry. Modelled on the domestic system of county based yeoman defence, it was thought that these enlisted educated middle class men would perform well on the battlefields. The fatal assumption was that these “men of a better class“ led by officers drawn from the gentry was ideal fighting material. But there was insufficient training and too many “slippages” in recruitment and officer selection, which meant that many of the volunteers could not shoot or ride and the whole amateur approach came in for some sharp criticisms by Lord Kitchener and the Lieutenant General Lord Methuen. But what is even more remarkable was the assumption that these Yeoman recruits needed their own private hospital funded by charity. In a very short time it was a huge success.

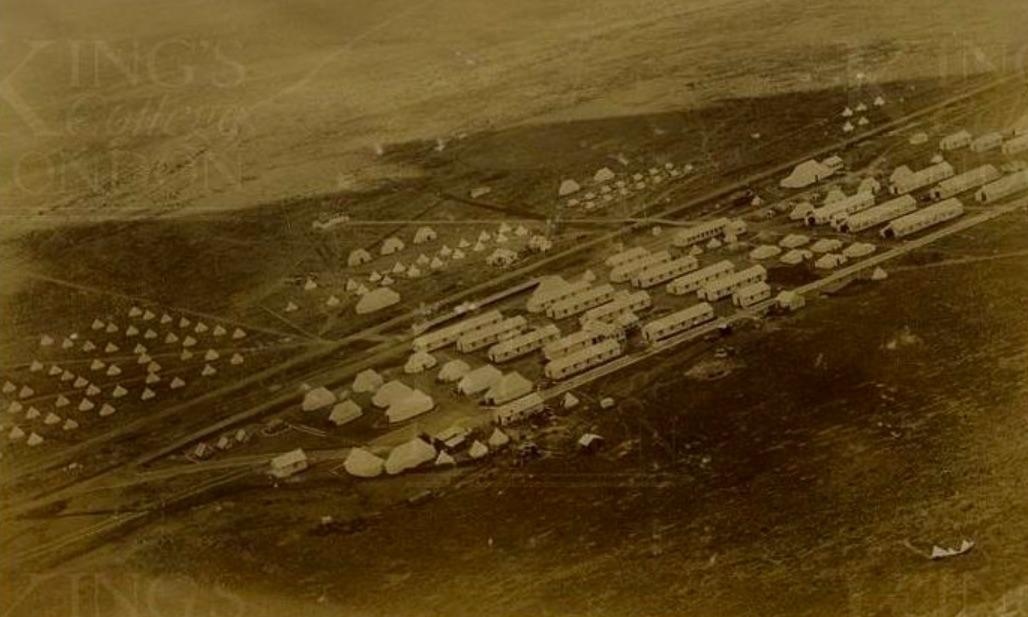

This book relates the story of the hospital and the men and women who cared enough to establish an extraordinary place. Deelfontein became part of Anglo Boer War history because of its part in the medical history of the war. A private state of the art, British military hospital was established in record time at Deelfontein; it fell outside the Army system and was created because of charitable efforts of two aristocratic ladies – Lady Georgina Curzon (she was the daughter of the Duke of Marlborough) and Lady Beatrice Grosvenor, Lady Chesham (daughter of the Duke of Westminister). Their organizing ability and their committee structure brought out the best of talents to bring in support in money and kind, enabling them to employ doctors, nurses, orderlies and ward maids.

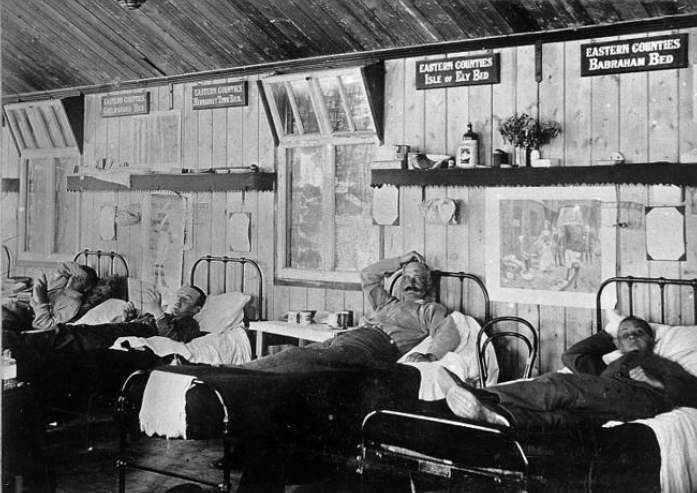

The objective was to provide a high quality facility for the Yeomen soldiers, but it seems that all British soldiers, a few wounded Boers and even local residents were helped. In total about 6000 patients were treated here during the period 1900 to 1901.

Beds at Deelfontein were endowed

For a very short period - it seems the experiment lasted for just over a year - the Imperial Yeomanry Hospital at Deelfontein became the best equipped, most sophisticated medical, surgical and convalescent hospital of the War. In addition to Deelfontein, there was also a Field Hospital and Bearer company which handed over 2600 cases on the field, hospitals and homes in Pretoria and even a small convalescent home in Parktown Johannesburg. Part of the success of the enterprise was to publicise and report on the achievements; hence a critical document is the June 1902 Chairman’s report; from this we learn that there were 706 staff members in total, 1960 beds were provided and over 20 000 patients were treated.

The Boer War was a humiliating and costly war for both sides; the two Afrikaner republics were ultimately defeated and with the unequal resources it was an unwinnable war. Boer losses were 4000 men in action but a more bitter legacy was the loss of about 28 000 Boer women and children in concentration camps; nor were Black losses insignificant. For Britain it was a war that cost £220 000, leaving 22 000 British soldiers dead but only 8000 were battle field casualties, 65 000 were invalided out of the British army but even more surprising was the figure of 8000 men who died of typhoid. There are 134 graves in two burial grounds; here is a microcosm of war, loss and the sacrifice of young lives.

The cemetery lay a quarter of a mile from the hospital; it is still there. But almost all of those buried at Deelfontein died of disease – the most likely cause of death was typhoid. Most of the graves at Deelfontein are marked with what are called Guild Crosses, placed on the graves by the Guild of Loyal Women. There is an entire chapter in the book on the graveyard, the memorials and the men who died at Deelfontein including the six staff members. I found this last chapter the most poignant. The appendix in this book records the names and details of all of the men who are buried at this remote spot. This is a valuable database.

Deelfontein Cemetery (Booktown Richmond)

It is a strange story of energy, cooperative effort, experimentation and delivery. The book provides many thumbnail sketches of the various men and women involved in that brief year’s commitment. These cameos together with the maps and many photographs give an insight into what Deelfontein offered and achieved. This is a book rich in detail - almost like a detailed and carefully drawn corner of a tapestry on a much larger canvas; its strengths and fascination lie in the detail and this pointillist approach; the weakness lies in the lack of critical commentary and taking the longer term view of the failures of the British medical system and what this then meant for later wars and in particular the First World War.

The Second Anglo Boer war was both the last of the heroic colonial wars of the 19th century and the first of the modern wars of the 20th century. It was a barbaric war in so many ways – the men of the British army were so often expendable; they were the cannon fodder on the battlefields. But the methods of war were also shocking and the Kitchener tactic of laying waste to the farmhouses across the veld and herding women and children into concentration camps following the fall of Pretoria and Johannesburg and the coming of the guerrilla phase showed little care for civilians both white and black. The British army organization and administration of the concentration camps was initially inappropriate, inefficient and inhumane. There was a dreadful lack of the basics of clean water, sanitation, fuel and soap. The camps were established by the British army at roughly the same time as the operation at Deelfontein was flowering and then brought to conclusion. Here is a possible big picture comparison. Death from disease rather than weapon was a plague for civilians and soldiers. Had the concentration camps been run by a private charity as was the Deelfontein Hospital would there have been a better and more humane outcome. On the other hand, the Anglo Boer War did see men in uniform being treated with some simple humanity as shown in the chocolate tin gift scheme of Queen Victoria for end of year festivities of 1900; tons of home comforts were sent by private donors to the troops – chocolates, sweets, socks.

The Anglo Boer War also anticipated many of the strategic and organizational tactics of the First World war with the disasters of death by disease becoming a red warning light for how not to expect men to fight and cope in trenches on battlefields. The volunteers of Kitchener’s Army in the FIrst World War were far better treated than the Anglo Boer War regiments and companies. Deelfontein and the companion military hospitals stand out as a beacon of what was possible and why men (or indeed women and children) at war should not be expendable. It certainly seems that despite our so called evolved and civilized lofty status of the world in 2022, the conflict in the Ukraine shows that mankind has learnt nothing from history.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven. She is also the Chairperson of HASA.