Girders on the Veld. Structural Steel and its story in South Africa. Eric Rosenthal. Published by the South African Institute of Steel Construction, 1981, first edition, illustrated 138 pages.

Eric Rosenthal was a prolific writer. He died in 1983 aged 78. He spent his career as an author, radio personality and journalist but If you check out his profile online his life only earns a paragraph on Wikipedia and a listing of approximately 50 books (and there were many more). He was one of those extremely clever people and for years he was a household name in South Africa because he was one of the “three wise men” on Springbok Radio's popular “Test the Team” quiz show, along with Professor Arthur Bleksley and Grant Loudon. Dewar McCormack was the quizmaster. I grew up with that programme, when radio was the theatre of the mind and your imagination was shaped by words and sound. The programme ran from 1957 to the early 1980s.

Rosenthal is still a name among Africana book collectors, because his many book titles turn up regularly (being so popular in their day they sold well, had long print runs and so many survive). Rosenthal was a polymath; he knew something about everything. But Rosenthal was too clever and too successful for his own good or for the good of his legacy as a writer. He wrote far too many books and did them in a journalistic style, so much so that I cannot think of one Rosenthal title that is an essential classic. Too many of the Rosenthal books were pot boilers because his eye was on their readability for the people who listened to the quiz show. Nonetheless his books still hold a place of some affection in my library simply because he wrote them and wrote so many across diverse topics and subject areas. You can download the full texts for free of 33 of his books. That must be a record of some sort. Rosenthal was educated as a lawyer and was an early graduate of the University of the Witwatersrand, but with a talent for writing he switched to journalism and writing. He worked for Alistair Macmillan on the three volumes on Johannesburg and Pretoria and environs and pushed through to publication Homes of the Golden City after Macmillan’s death. That was a great accomplishment.

Rosenthal is also described as an historian and here I disagree, he was not a scholarly writer as this particular book reveals. Someone who writes history as an acclaimed historian needs to pursue deep research, keep detailed records, compile index cards of source material, cite references, acknowledge where his work fits in relation to what other historians have written about the subject. The books of a good historian include footnotes or endnotes, a bibliography and an accurate index. I say this in the context of the particular book before me, Girders on the Veld: Structural Steel and its Story in South Africa, which has not a single footnote, reference source, bibliography or index. Rosenthal was a generalist and not a specialist; he had all the confidence to tackle any subject if his publisher or a company commissioned him. In that sense he was an entrepreneur of non-fiction South African informative books and history but taken “lite”.

Book Cover

This book was published in 1981 by the South African Institute of Steel Construction and marked their 25th anniversary. It was a late book in his career as Rosenthal died two years later. This is the genre where Rosenthal excelled - those business, institute and company histories commissioned by a firm or organization to celebrate a landmark anniversary. At first glance this is a book to tantalize and tempt with excellent black and white photographs of people, places, steel structures, railways, bridges, sketches and drawings. It all looks, well, riveting. It is an easy read and it looks like an essential title for the architectural and economic historian. The chapter headings are clearly set out and promising and romps through metal roofs to metal bridges, tower blocks to skyscrapers, warfare, the military uses of steel and ammunition and then leads into the history of creation of a local iron and steel industry and the formation of the South African Institute of Steel Construction and what work the Institute of Steel Construction did as an independent promoter of the structural steel industry. Most promising is the discussion of the relationship of engineers and architects. South Africa owed much to men like Sammy Marks and Jack Eaton, H J van der Bijl and a good many others who cross these pages. In a sense the book is a workman like popular book that must have pleased the Institute.

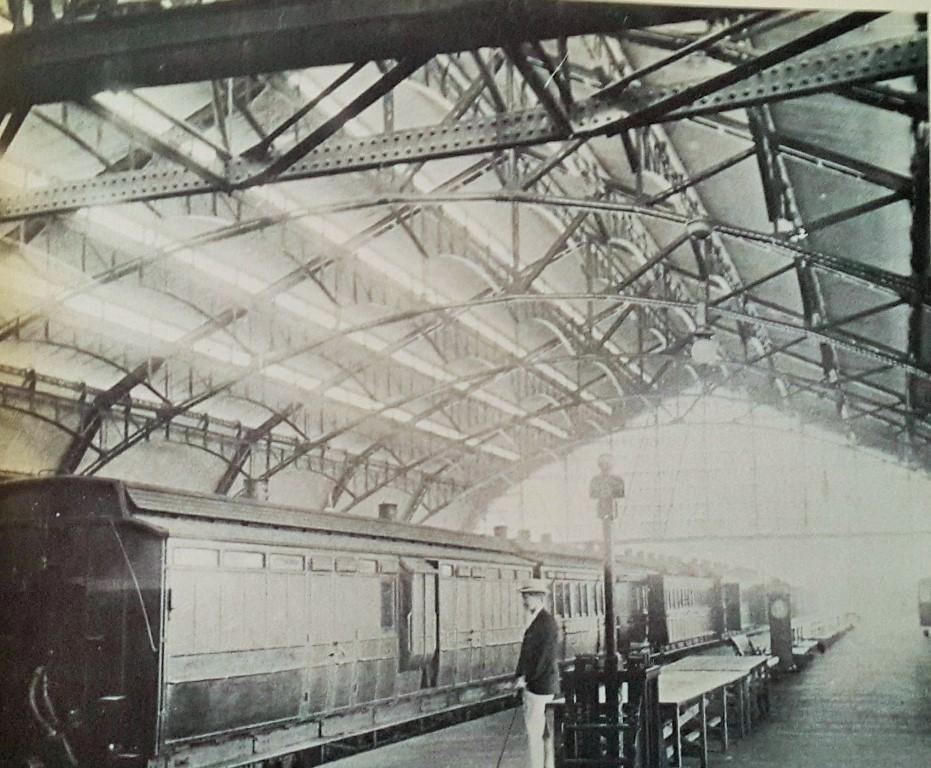

Durban Station Platform (Photograph appearing in Girders on the Veld)

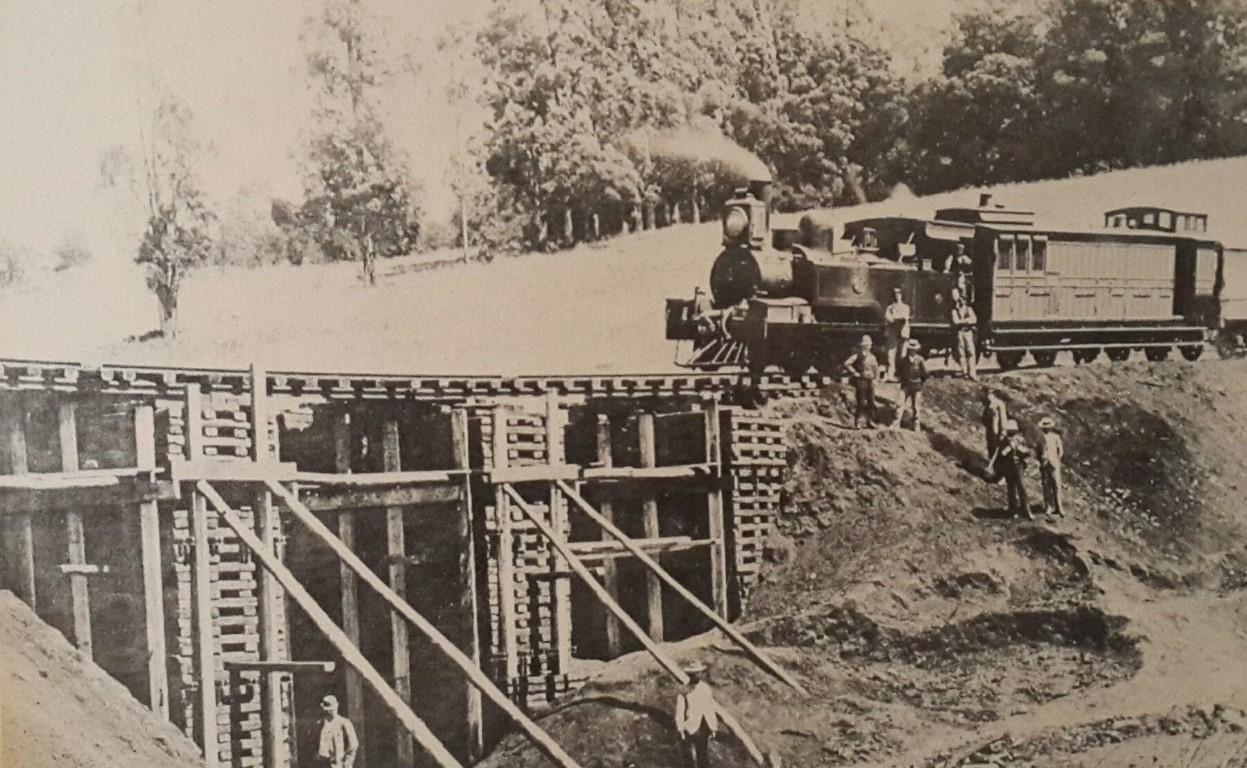

However, the volume has serious shortcomings as a source of real history as Rosenthal fails to reveal where he did his research (it is clear he read widely and must have undertaken research). Any serious historian coming after Rosenthal will need to re-tread the archive documents, redo the research from scratch to pin down all these sources. Rosenthal never documented where he found his facts, at least not within the covers of this book. In my opinion there is no contribution to history here. If there is no documentation, it could all just be a “thumb suck”. It is a tragedy and all of Rosenthal’s strengths and weaknesses are revealed. I think the book for these reasons did a disservice to the Institute that commissioned the volume (they must have paid a handsome fee) as it is at their expense that the book turned into a vanity effort. Yet it need not have been that way as it is a stunningly important story of the shift from the steel people being merchants and importers of a vital material imported from Britain and Europe to becoming local producers and how and why government effort mattered to establish ISCOR. You could not build bridges or cross the veld by rail without iron and steel but you needed roads and railways to the interior to import the steel from the ports. Steel mattered for the building of Johannesburg and the crucial switch in headgear from wood to metal. Our heritage structures that we prize and admire today are steel framed.

Komatipoort Bridge (Photograph appearing in Girders on the Veld)

Whether one needed government intervention and whether a country should have a nationalised steel industry is a discussion that eluded the author. How much should politics and ideology (whether it was in 1924 or in 2016) enter into the structuring of a major industry? Steel was at the core of an industrial revolution and the South African economy would never have achieved maturity as a modern participant in the international economy without the talents and efforts of men who shaped the steel industry. A good history of the early days is still relevant to guide those in government who make disastrous decisions today about ownership structures, the award of tenders, sourcing raw materials, production systems and the price of steel.

There is another sense in which the Rosenthal volume falls short. He fails to explain why steel underpinned the industrial revolution, what is steel, how does it differ from iron, what are the distinctions between cast iron and wrought iron and then steel (it’s all about the chemistry of getting the carbon percentages right). Anyone wanting to read about the industrial revolution and how a steel industry emerged in other countries should first tackle David S Landes’ The Unbound Prometheus: Technological Change and Industrial Development in Western Europe from 1750 to the Present is an influential economic history book published in 1969 well before Rosenthal’s book and which should have been the starting point for his local history. The story of steel in South Africa has also to be related to mining endeavours and the extraction of iron ore and there is very little about this side of these pioneering mining efforts. I found the adverts and business cards of different local companies inserted by Rosenthal a curiosity and an irritation. The book has an abrupt and truncated ending. There is no conclusion to draw his story together.

But to remember Eric Rosenthal with a glass of bubbly to hand, I should conclude by raising my glass to a talented journalist in the hopes of acquiring another Eric Rosenthal title. Why bother? Because he was so prolific, was a clever writer and a run of Eric Rosenthal titles is no bad addition to a local library even if your shelf does not groan with erudition. I suppose my advice is to appreciate Rosenthal from his corner.

2016 Price Guide: R150 bargain buy on the internet to well over R1000 – R1500 and becoming a rarer title.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories.