Joline Young’s new book, “An uncomfortable paradise” takes us on a journey, part personal, part historical, and a South African history that few know of – early colonial life in Simons Town. Modern day Simon’s Town is a tourist hub in which South Africa’s naval base provides a quaint, if slightly militaristic, backdrop to charming coffee shops, pleasant bed and breakfast establishments, design emporia, emblematic vistas of sea and mountains, a penguin colony and multiple iconic colonial memorials, not least the fetishised statue of a naval dog. But the true history of the area, like almost all of South Africa, long precedes British or Dutch appropriation. It is a history of which the last 4 centuries has been built on the dispossession of indigenous peoples and the expansion of colonial domination, which was dependent on the import of enslaved people to the colonies and the brutal exploitation of their labour. The book also exposes the incredible injustice and arbitrary brutality of colonial law, which is described through the human stories that have emerged from Young’s archival research.

Book Cover

While it is the latter narrative of the oppression and resistance of enslaved people that attracts Young’s primary attention, she makes sure to weave into her stories the experiences of the indigenous people of the area. She does so in a way that many historical narratives miss, either dwelling on slavery’s brutality or on the colonial machinations of dispossession of the indigenous people. Young has brilliantly captured the commonality of experiences shared by peoples oppressed by the workings of colonial empire. This is a particular strength of this account.

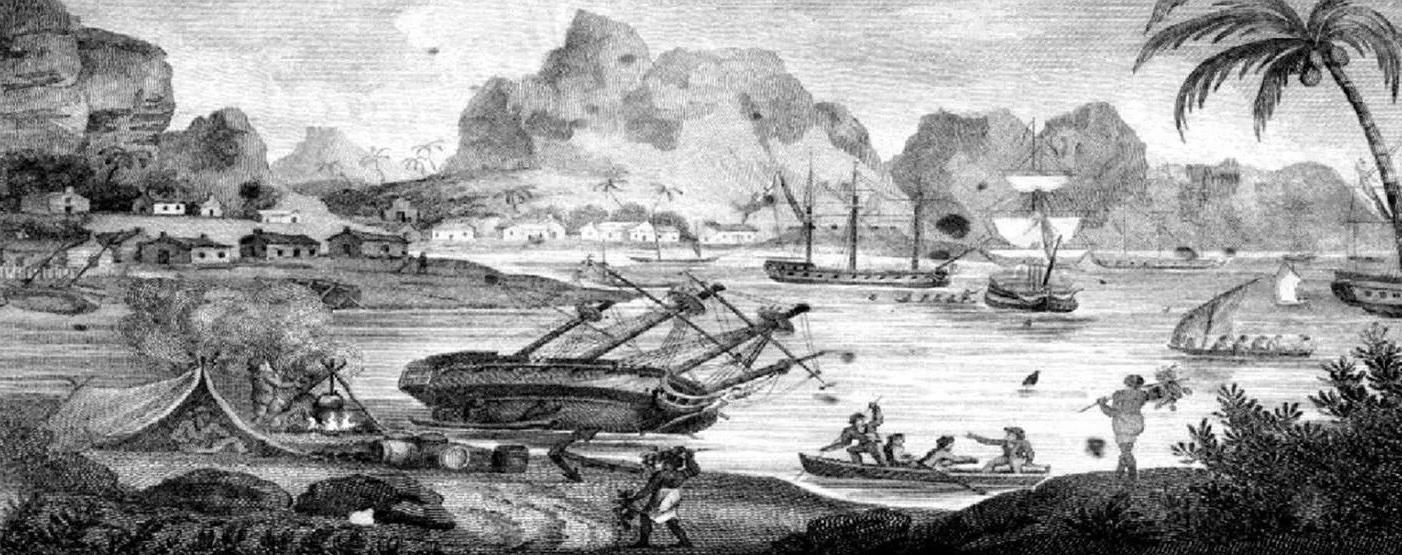

Simon’s Bay, as it was then known, was a ‘hidden and secluded area, a long trip away from the heart of the Dutch colony at the Castle in Cape Town and on a route that involved circumventing mountains and treacherous quicksand. So, while the outpost of Simon’s Bay enjoyed the same cultural, political and social dynamics as the rest of the early colony, it was a smaller and more intense intermingling of enslaved people, indigenous Khoe Khoe pressed into labour, venal settler opportunists, colonial appointee officials loyal to rules of injustice, a reverend as cruel and brutal as the worst slave owner, and entrepreneurial farmers (some successful, some foolish, some dissolute) all in a melting pot of relationships that Young describes so vividly as “unequal, often cruel, multifaceted and complex.”

Young quite generously recognises the fact that many of the employees of the Dutch East India Company (known as the VOC) who arrived in the Cape were actually the products of deep poverty in Europe and exploitation by wealthy gentry, whose experience of impoverishment and dispossession propelled them into service for the VOC. Of course, as in many historical settings, the victims of such experiences, when they acquire any power themselves, soon translate their own impoverishment and dispossession into the treatment they mete out to those with less power – in this case indigenous Khoi herders and enslaved people of the Cape. And Young unearths these stories flawlessly.

The searing account of how slavery dismembered families, separating husbands from wives, parents from children and children from their siblings, and controlled enslaved people through the worst forms of brutality, is rendered in excruciating detail in Young’s historical analysis. The ability of almost all slave owners to overlook the humanity of their chattel is all the more poignant when Young provides account of some slave owners seeking to do right (in the historical context) by, for example, writing into their will that their female ‘slave’ should not be separated from her daughter. One can only wonder that if some slave owner’s wife could see her servant as mother, daughter, sister or spouse, then one might ask what social and/or psychological mechanism operated for the majority of slave owners to deny the humanity of their human chattel. Young’s account does not explore such questions in any detail but makes the asking of such questions inevitable when reading her descriptions.

Joline Young

Young’s account considers how incoming enslaved people might have been wondering if their new owner would be cruel, but with no way to change their circumstances if it were the case. Enslaved females were set to work in slave owners’ homes; male workers doing hard labour building homesteads, and work on the farms.

Working in the home may have had some advantages for enslaved women, but Young’s account makes it clear that sexual exploitation of enslaved females was not uncommon and, moreover, that the degree of consent to such relationships was highly heterogenous. The fate of children born from enslaved mothers and colonial fathers largely depended on whether and how the father acknowledged the child, despite elaborate colonial rules concerning the fate of such children. If the father ignored the child, he or she would grow up a ‘slave’, without a childhood and subject to the arbitrary and often brutal conditions which enslaved people endured.

If the father married the mother, the child would likely be able to enter the world of colonial society as a burgher. As a result, Young points out that many Afrikaner families are able to trace ancestry to a formerly enslaved female ancestor. Indeed, some years back, I attended a Summer School lecture at UCT on Angela van Bengalen, one such freed enslaved woman who then became a successful entrepreneur in the Cape Colony. At some point, the speaker paused her presentation, and asked the audience if anyone thought they had ancestral links to Angela. A large number of hands went up, hands of persons who would have been classified as white during apartheid, reflecting the extensive lineage of slavery in Afrikaner descendants that is only now being recognised.

Two quite extraordinary insights emerge from Young’s book.

Firstly, as Young explains, being freed from slavery did not necessarily yield the improvement in one’s life chances you might anticipate would result. Cunning and deceit are the words that come to mind to describe how early colonists, when faced with the imminent lifting of the institution of slavery, found ways to circumvent the formal abolition of slavery by creating indirect forms of compulsory servitude, often hardly distinguishable from slavery. The fiction of “apprenticeship”, purportedly meant to enable enslaved people to acquire skills to enter the labour market, was, as Young illustrates, a “guise to extend slavery for another four years.” Unscrupulous slaveholders also used loopholes in the Abolition Act to prevent enslaved children from being freed. Even when officially manumitted, numerous enslaved people were simply not given ‘free black’ status for years, with no consequence to the owners. How cruel it must have been to have your hopes raised of a life free of cruelty and arbitrary controls, only to find little has changed.

Secondly, during the period when abolition of slavery was gradually unfolding, English colonists took advantage of abolitionist politics to capture slaving ships and ‘free’ the human cargo. However, freedom was not the objective of this ‘emancipatory’ action since the ‘freed’ slaves were integrated into a form of servitude in the colony as ‘prize negroes’. Such a description was also deeply oxymoronic, since the people captured as ‘slaves’ at sea were not only from Africa (but also from South and East Asia), nor were they prized in any way other than for how well they could boost the colonial economy and the wealth of individual colonists. Prize negroes were a captive category of ‘non-slave’, who continued to be exploited in ways that showed little difference from formal slavery. Since both enslaved people and ‘prize negroes’ in Simon’s Town were often people from the East Indies, Simon’s Town saw the growth of a thriving Muslim tradition. Following the Muslim faith gave many enslaved and indentured persons succour through their hardships and this heritage lives on in Cape Town’s ‘Malay’ traditions and beliefs and is finely etched in Simon’s Town’s current landscape, despite efforts by the Apartheid planner to obliterate such history in the town through Group Areas removals.

We also learn through Young’s account of the very unusual community of Kru people, an indigenous ethnic group from West Africa, who came to Simon’s Town in the first half of the 19th Century not as ‘slaves’ or indentured workers but, remarkably, as early migrant labourers. They were highly sought after by merchant ships, because of their reputation for seafaring, and because unlike white sailors, they were not vulnerable to tropical disease. They established close-knit communities and played important roles in labour for the naval activities in Simon’s Town, contributing to the diversity of Simon’s Town at the time, and to many descendants of Kru origin throughout the Cape today.

However, what sets Young’s book aside is not just her meticulous attention to detail, but her realisation that her own roots were to be discovered and uncovered in this account. Young’s connection to slavery in her own forebears is deeply personal and moving. Although she does not write to an explicit named ancestor, you can hear in Young’s Message to My Enslaved Mother (with which the book concludes), the aching imagining of how one’s ancestors might have survived a life of such cruelty. To be separated from your children and not know where they are, to be haunted in your dreams by their cries, to have to deal with feeling that we might today call outrage, when you have so little power. We cannot fail to be moved by the idea that one’s ancestors lived through, and survived, such brutality.

What I also found so valuable was Young’s detailed respect for the protagonists in her accounts, who are not just archival records but people, sometimes brought to a strange land, sometimes coerced into labour, victims of systematised violence but also people who found love amidst extraordinary adversity or whose skills proved valuable to their owners, and so were able to negotiate a less tortured course as ‘slaves’ and labourers in the colonial environment. They are the ancestors of most of Cape Town’s people, one way or the other, and their stories deserve telling. Joline Young has done that telling, to the benefit of us all.

Leslie London is a Professor of Public Health Medicine at the University of Cape Town and Chair of the Observatory Civic Association.