Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

A motto developed by myself over the years in my ongoing search for elusive historical photographs is: “Do not underestimate what could be found in drawers or little boxes”, resulting in me always curiously opening drawers or boxes when visiting antique shops, charity stores or attending car boot sales in that they may just contain some photographic surprises.

It then so happens that I opened a small Royal Arms Specials cigar box in a coastal antique shop a few years ago. What did it contain?

Some one hundred photographs from the Anglo-Boer War period. This cigar box was found in one of my favourite antique shops in Kalkbay (a shop that sadly no longer exists). Kalkbay, a coastal town in the Western Cape, has always been a reliable source for finding antique South African photographs.

On analysing the content of the cigar box, the original amateur photographs (8,5 x 8,5 cm in size) were found to be images captured by the war correspondent David Steward Howie. Howie was attached to the newspaper Times of Natal.

The photographs are not of professional quality but have become valuable historical documents in their own right.

Most of the photographs, with some duplication, were pasted onto pieces of paper on which Howie captured handwritten notes. Although McCrachen (2015) only has Howie recorded as a reporter for one publication, the assumption must be made that the duplicated images were possibly meant for another publication.

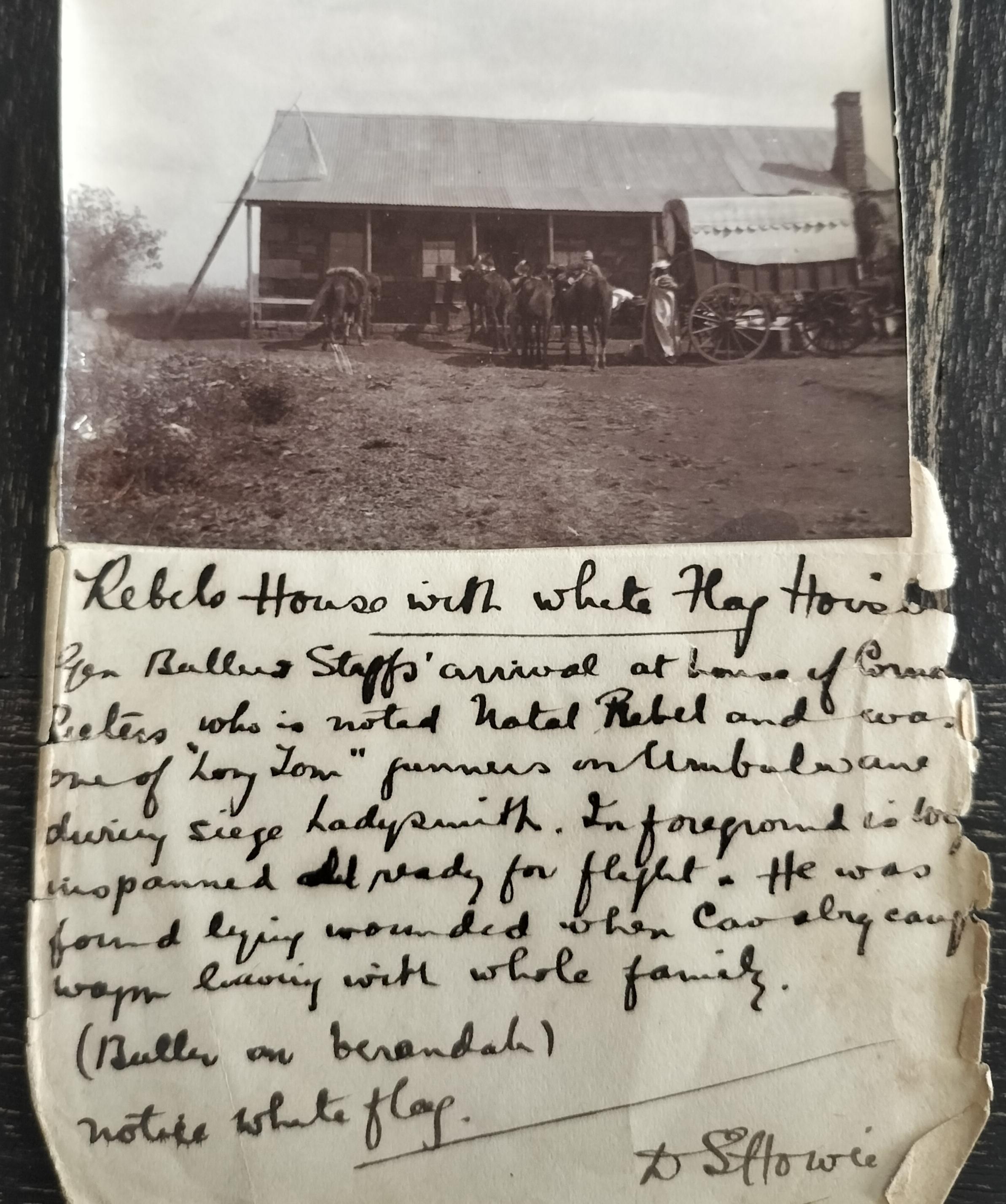

The piece of paper stuck to the photograph by Howie states the following: Rebels house with white flag hoisted. Gen Buller staff's arrival at house of Cornelius Pieters who is noted Natal Rebel and was one of the "Long Tom" gunners on Umbulwane during siege (of) Ladysmith. In the foreground is the wagon outspanned and ready for flight. He (Cornelius) was found lying wounded when Cavalry caught wagon leaving with whole family (Buller on veranda). Note white flag.

Close-up of the same image above

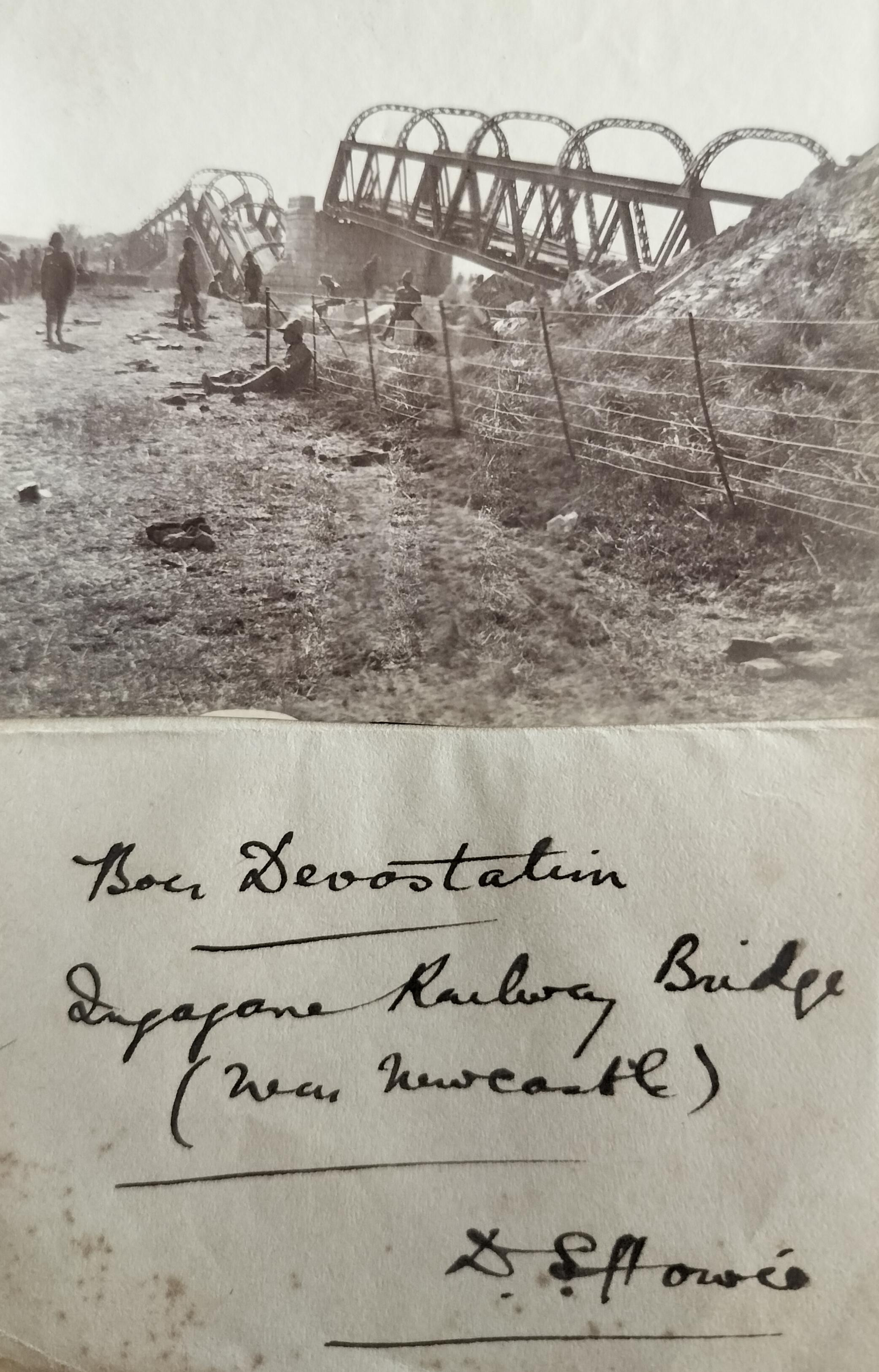

Destroyed Ingagane railway bridge containing Howie's notes

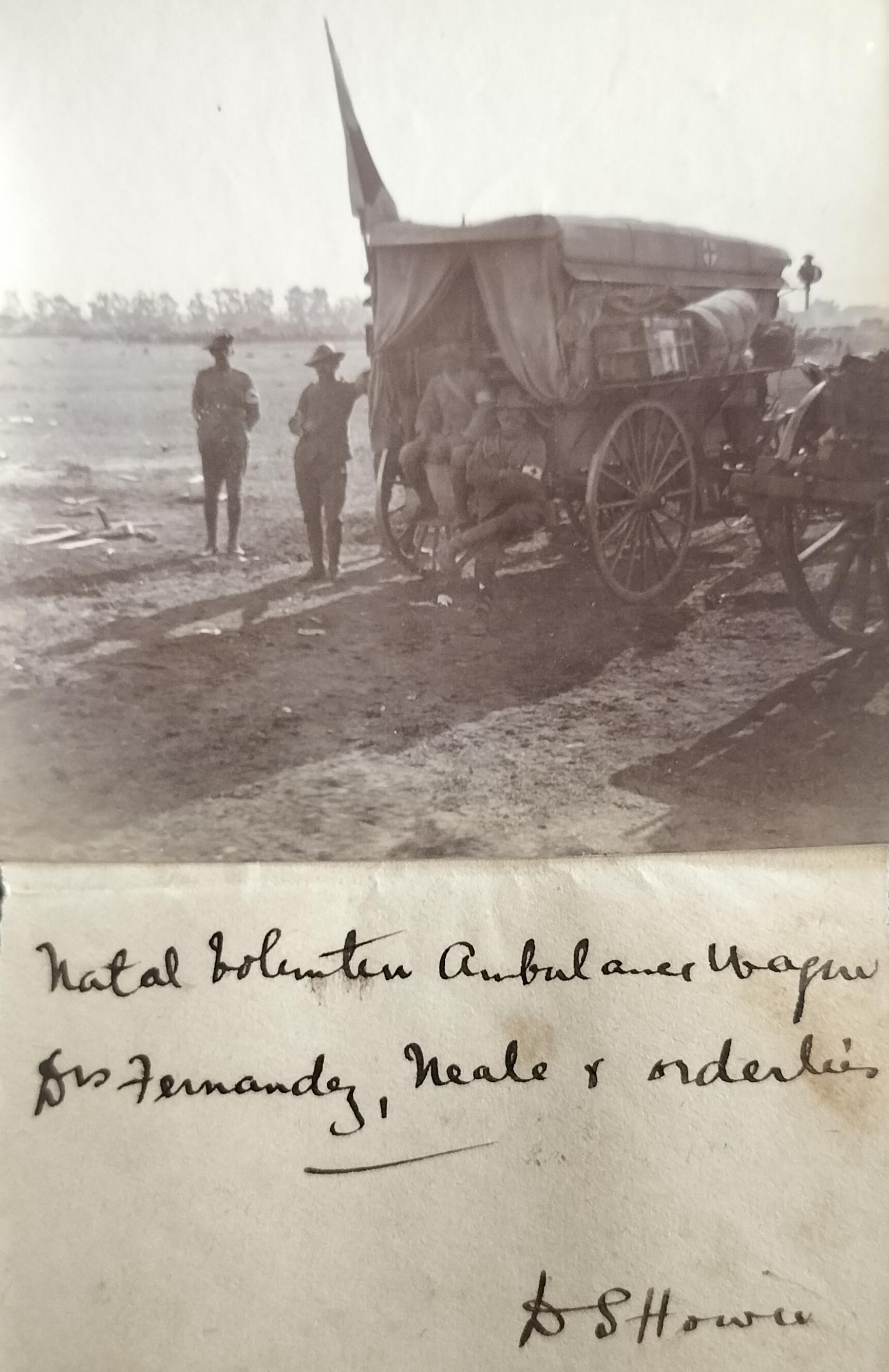

Natal Volunteer Ambulance and wagon with Drs Fernandez, Neale and orderlies at an unknown location

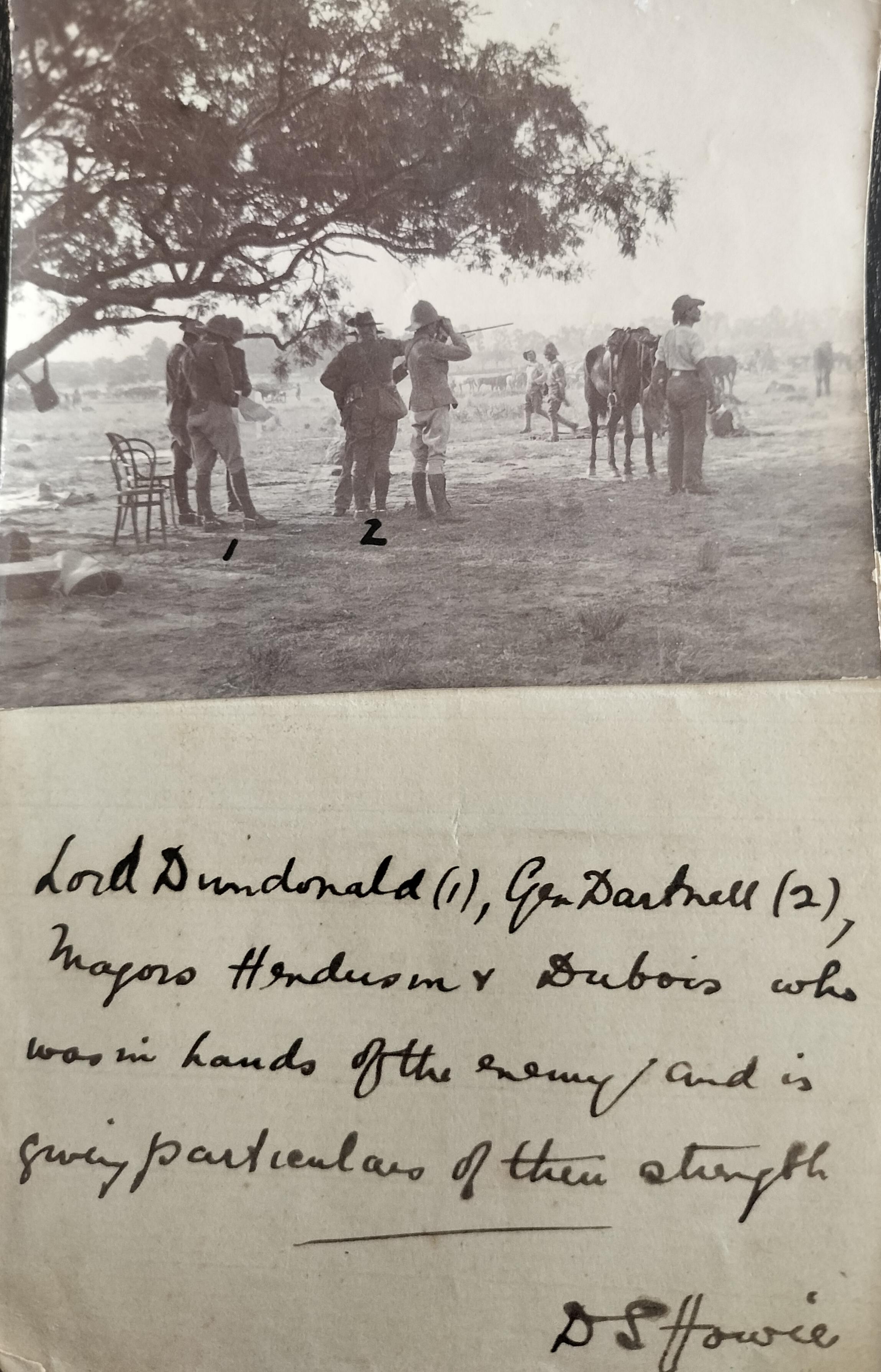

Lord Dundonald (1) and General Dartnell (2) with majors Henderson and Dubois. Dubois was in the hands of the enemy (Boers) and is seen giving particulars of their strength to his superiors. David Henderson was the director of British military intelligence during the Anglo-Boer War.

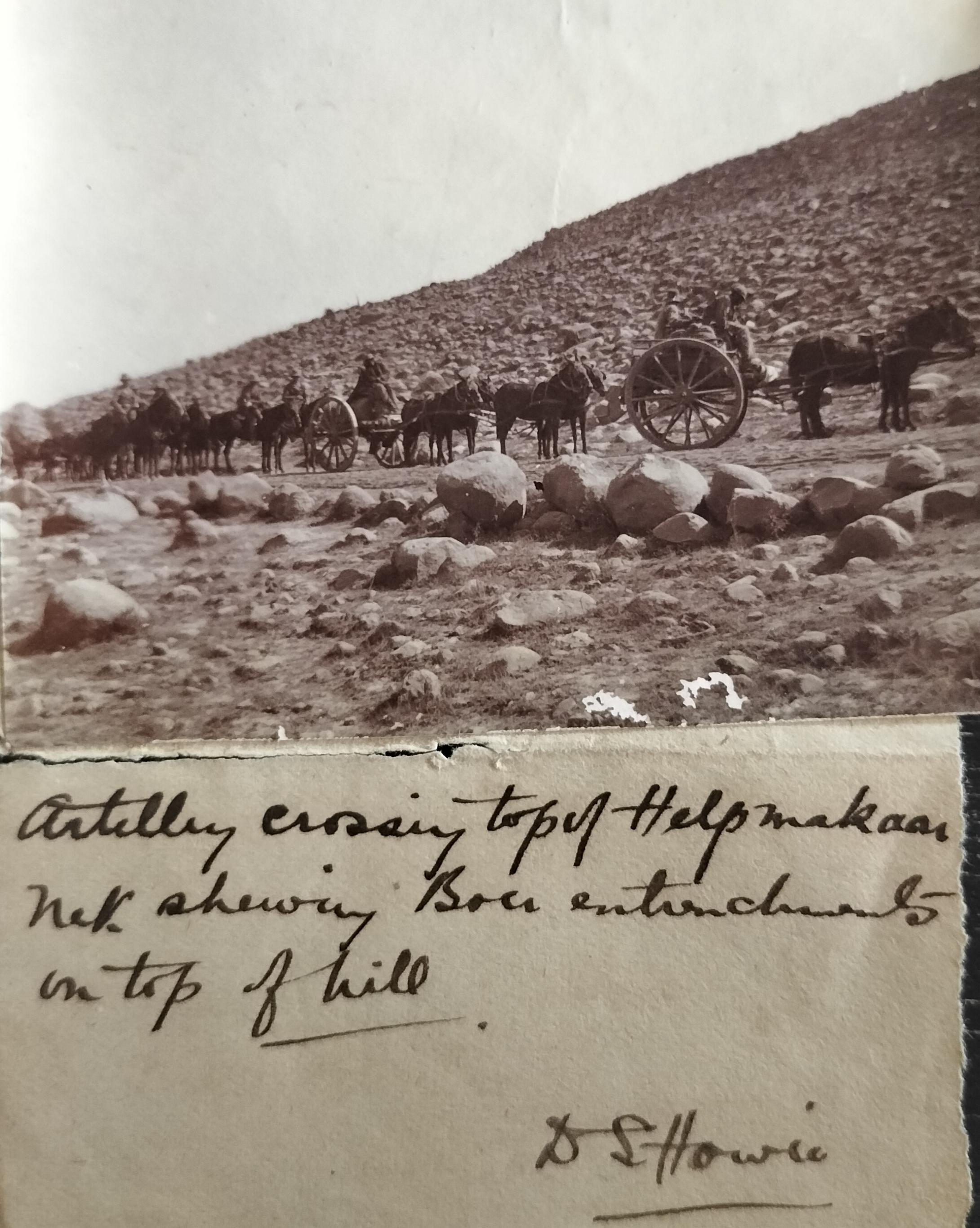

British Artillery crossing the top of Helpmekaar Nek showing Boer entrenchments on top of the hill

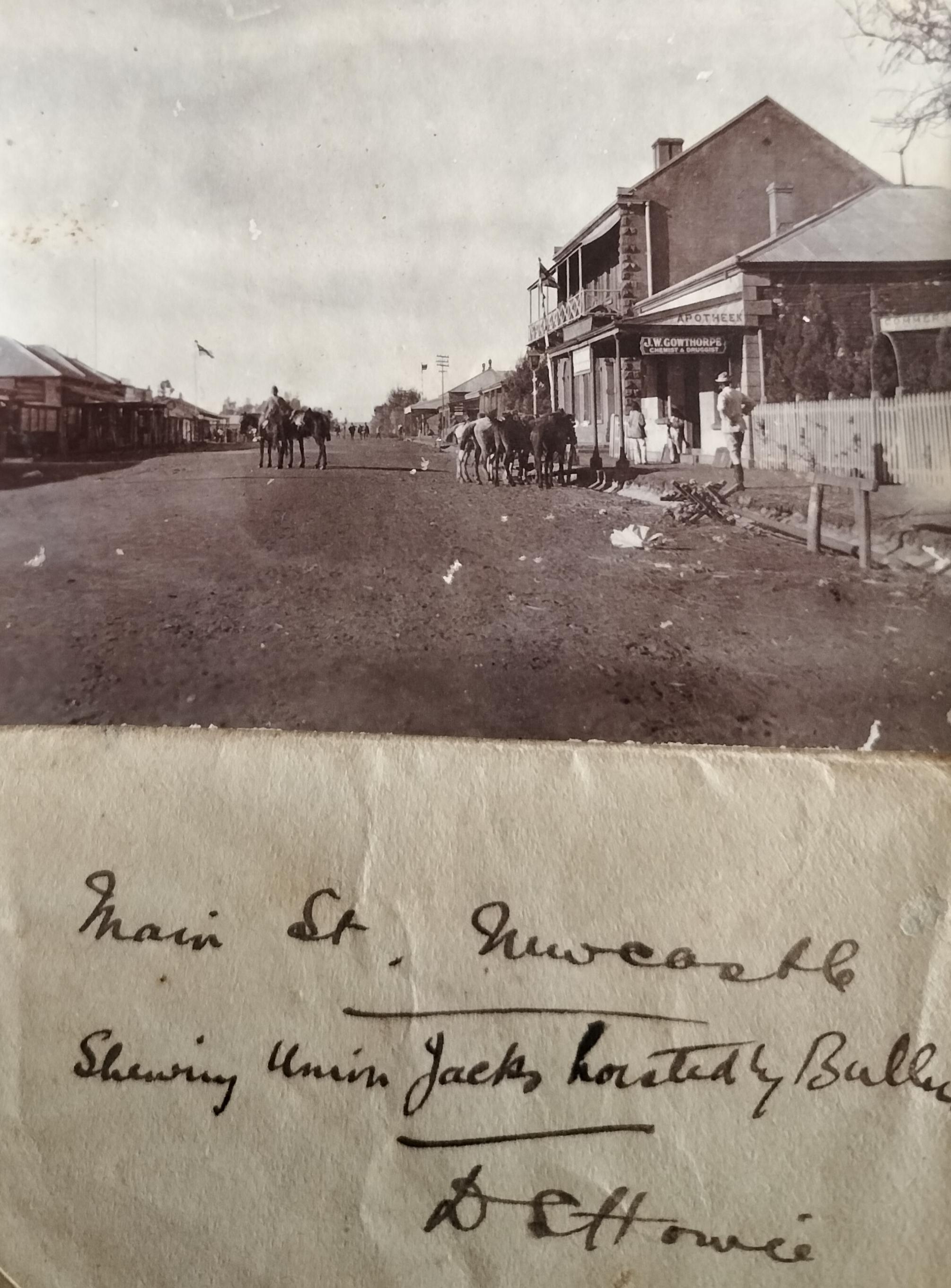

Newcastle main street showing the Union Jack in the distance hoisted by Buller. On the right, the pharmacy owned by JW Gowthorpe can also be seen.

A further assumption is made that none of these images were ever submitted by Howie to any publication and that Howie held them back, or could it be that the images originated from the Times of Natal? Unlikely.

The photographs in all probability landed up in the antique shop after inheriting family members either sold them to the antique dealer, or the dealer bought them at an auction.

Nevertheless, another significant little photographic collection has been rescued from potential destruction by being mindlessly discarded, as happens to so many photographs of significant historical interest.

The main intent of this article is to share the found photographs but in the same vein also briefly reflect on war correspondents during the Anglo-Boer War as well as the war correspondent DS Howie himself.

Correspondents during the Anglo-Boer War

The size of the press corps during the Anglo-Boer War was significant.

McCrachen (2015) suggests that during the conflict period (1899-1902) eighty-eight newspapers, journals, commercial companies, and news-gathering agencies employed at least 276 war correspondents. Some correspondents submitted reports for more than one publication.

Not all the war correspondents were male. Female reporters included Miss Bateman, Lady Briggs and Mary Kingsley from the Morning Post, Miss Maguire from Reuters, and Lady Sarah Wilson from the Daily Mail.

Research by McCrachen (2015) confirms that on the British front 49 British newspapers with 191 named correspondents and 8 South African newspapers with twenty-five named correspondents, as well as five news agencies with forty-seven named correspondents were active in the field at the time. Needless to say, they were not all in the field at the same time. With correspondents that came and went, this was probably the largest number of war correspondents to have covered an Imperial war in the history of the British Empire.

Reuters had the largest presence in terms of news reporters (28) followed by The Daily Mail (25).

McCrachen (2015) states that these figures do not include for example the unnamed German photographer who was caught by some British scouts on the top of Spioen Kop, piling up the bodies of dead British soldiers for ghoulish pictures. One of the scouts raised his rifle and, allegedly without a word, shot and killed the correspondent. Needless to say – I am immensely curious about who this photographer was and intend to find the answer in time.

Pretoria’s Grand Hotel was to become the general meeting place for many of these correspondents, several of whom were under a kind of lax house arrest yet had access to anyone who cared to pop into the bar of the hotel. So lax was security that on one occasion, a guard asked his journalist prisoner to look after his rifle while he went off to see his girlfriend (McCrachen, 2015).

If the press corps on the Imperial side were generally sympathetic to the British, it is largely true to suggest that their colleagues across the firing line tended to be avidly pro-Boer. Pro-Boer journalists included various American, nationalist Irish, continental European and even a few British journalists who covered the war from the Boer side.

The removal of Reuters’ general manager in South Africa, MJM Bellasyse, by Baron de Reuter, was the consequence of a British complaint of him being too sympathetic towards the Boers. Several other foreign correspondents and anti-British correspondents also got into serious trouble with the British at the time (McCrachen, 2015).

War correspondents were not left unaffected during the war in that some were captured, some died following them contracting fever, at least six were killed, some picked up injuries (one correspondent lost an arm), whilst others had stories to tell about their escapes. Lieutenant Winston Churchill, who reported for the Morning Post, is an example of a correspondent who was captured but managed to escape in Pretoria. Another correspondent, namely A. Graham from the Central News has even been reported as missing (McCrachen, 2015).

When the war commenced, Major Jones was the British censor in South Africa. His rules were so few that they were printed on the back of the correspondent’s licence, as the War Office credentials were called. One of Jones’ headaches was that dozens of war correspondents turned up, most from reputable newspapers, but few of them with the War Office licences issued in London in hand. Licenses could also be obtained from several military bases in South Africa, as well as in Cape Town. No British correspondent was ever refused a licence (McCrachen, 2015).

McCrachen (2015) continues by stating that by the time the war broke out in early October 1899, the War Office had issued only about thirty-six licences to 22 British newspapers and magazines, three United States papers, two Australian newspapers and two news agencies. The Daily Chronicle, Daily Mail and The Times each had two accredited reporters.

The chaos was further compounded by the fact that no single centralised list of war correspondents existed.

Correspondence around how to manage foreign correspondents reveals the chaotic and inconsistent way it was all handled. It was proposed that no more than two licences be granted to any paper and that licences only be granted to dailies with a circulation above 20 000, and that no foreigners be granted licences.

The issuing of licences to foreign correspondents on the British side became an issue when a German journalist, Dr. Richter, tried unsuccessfully to get one. As the adjutant general noted: “If it can be avoided, I hope that licences will be refused to all foreign correspondents – they are only spies.”

Even when the South African War was in progress, the British military censor ruminated on whether in any future war the Army was to be followed by photographers and cinematograph agents.

Post the Anglo-Boer War, 149 correspondents, representing forty-seven newspapers and journals, received Queen’s campaign medals. Sixteen journalists who had been nominated did not receive medals. For his work as a war correspondent, Howie was one of the war correspondents who received a medal.

Analysis of Howie’s Anglo-Boer War Photographs

Before making a career change late in 1900 or early 1901, Howie was linked to the Times of Natal. This newspaper seems to have employed only two reporters – the other was W. Cox. Hansen (2018) aptly described the Times of Natal as being jingoistic (extreme patriotism) towards the Brits.

From the notes captured underneath some of the photographs, it is clear where Howie’s loyalties resided in that he often refers to the enemy (the Boer in this instance).

British Cavalry taking possession of a Natal Rebel's house where a white flag was hoisted

Howie wrote the following underneath this image: In enemy country - Boer farmhouse flying white flag

Destroyed Ingagane railway bridge (near Newcastle). The bridge was destroyed by the Boers.

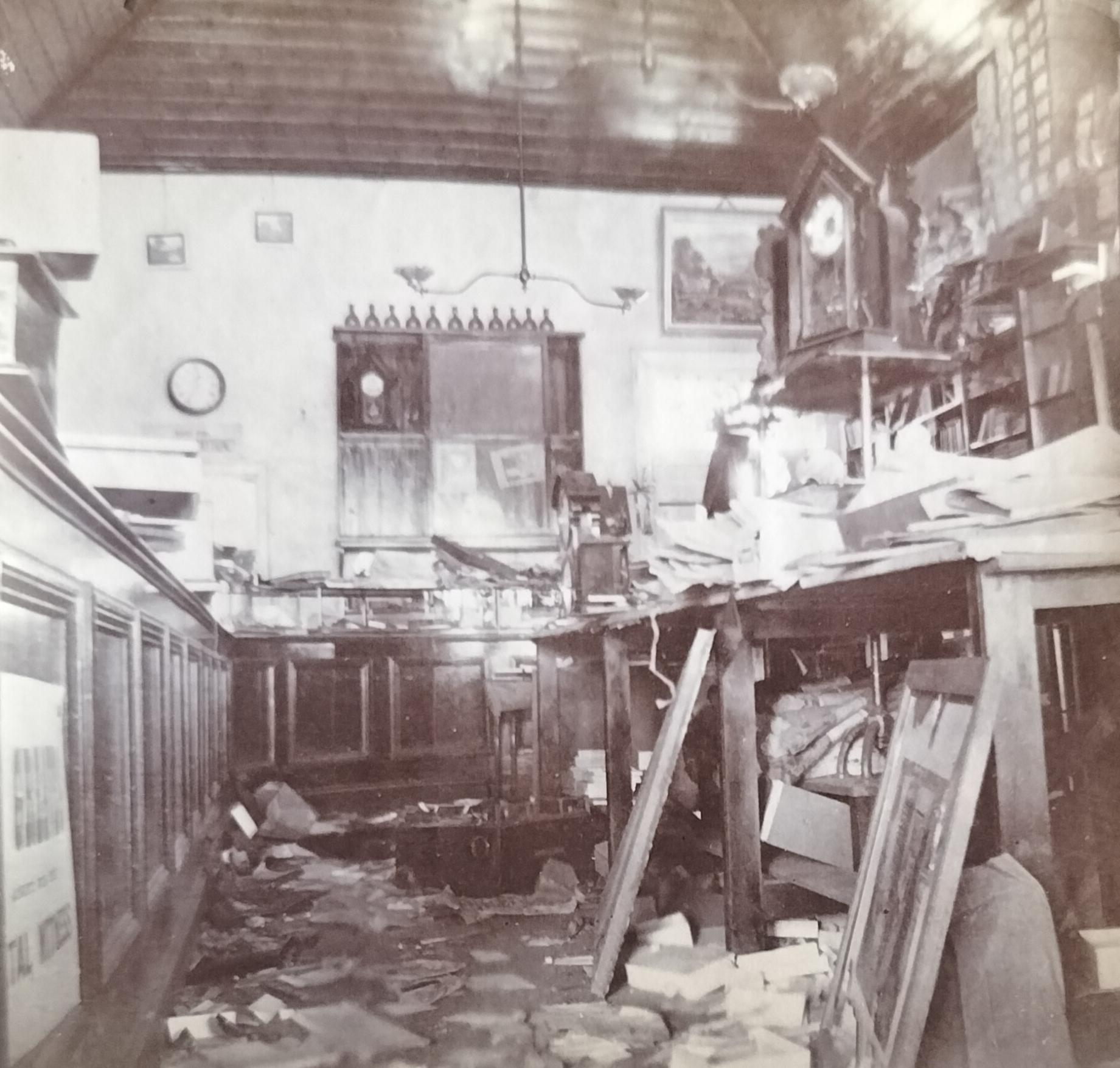

Wanton destruction. Interior of a looted jewellery store in Newcastle

Following the Siege of Ladysmith, the photographs, almost 125 years old, present a unique record of British movements in Northern Natal between March 1900 and June 1900.

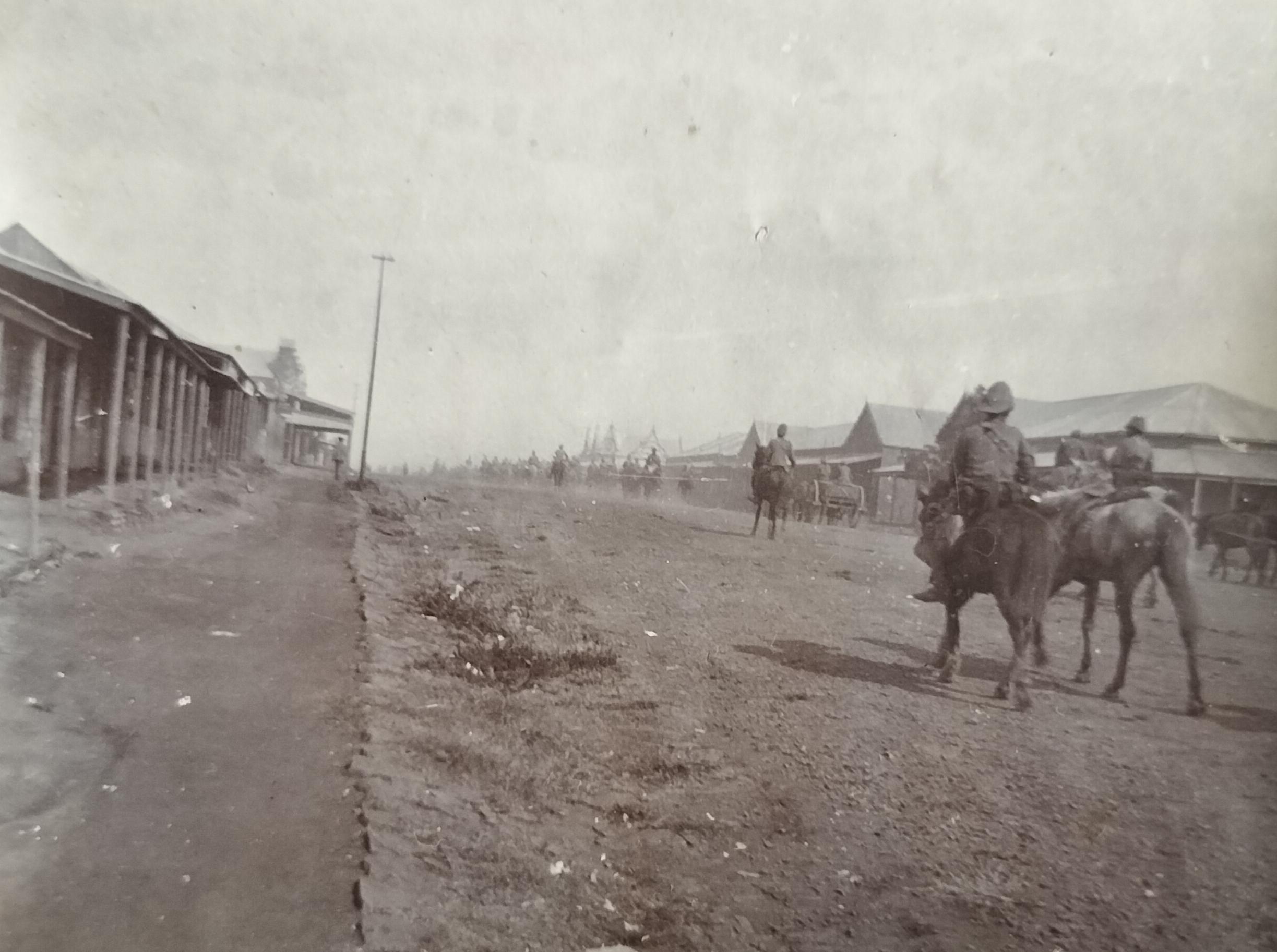

Howie and other journalists travelled with General Redvers Buller, who was heading up the Natal Field Force. Following the Siege of Ladysmith, Buller led the great northern advance on Machadodorp.

En-route, Buller and his men captured Dundee and Glencoe in May 1900 followed by Botha’s Pass, Volksrust and Standerton in June 1900.

On their trek between Ladysmith to Standerton, several interesting places were recorded by Howie, some of which include:

- Umbulwane near Ladysmith;

- Ingagane railway bridge near Newcastle which was blown up by retreating Boers;

- Helpmekaar, south of Dundee;

- Number of Dundee-related scenes, such as church and post office;

- Number of Newcastle-related scenes. Also includes images of a jewellery store that was ransacked;

- Amajuba mountains;

- Sundays River;

- Waschbank between Ladysmith and Glencoe;

- Ingogo between Newcastle and Volksrust;

- Laing’s nek west of Charlestown;

- Charlestown and burned hotel;

- Volksrust Hotel

- Kromdraai railway station between Standerton and Volksrust

- Standerton Kruger Bridge, Dutch reformed Church, and Magistrates Court;

General Buller and staff's arrival at the Dundee post office. According to Howie's notes, Buller is standing in the doorway of the building.

General Buller's troops entering the town of Dundee on the day it was reoccupied (15 May 1900)

St. James Anglican Church where the late General Penn Symon was buried showing the Union Jack hoisted by Major Henderson on morning of 15 May 1900 when Dundee was reoccupied. Symon was mortally wounded in the Battle of Talana seven months earlier (23 October 1899).

The Kromdraai railway station between Standerton and Volksrust

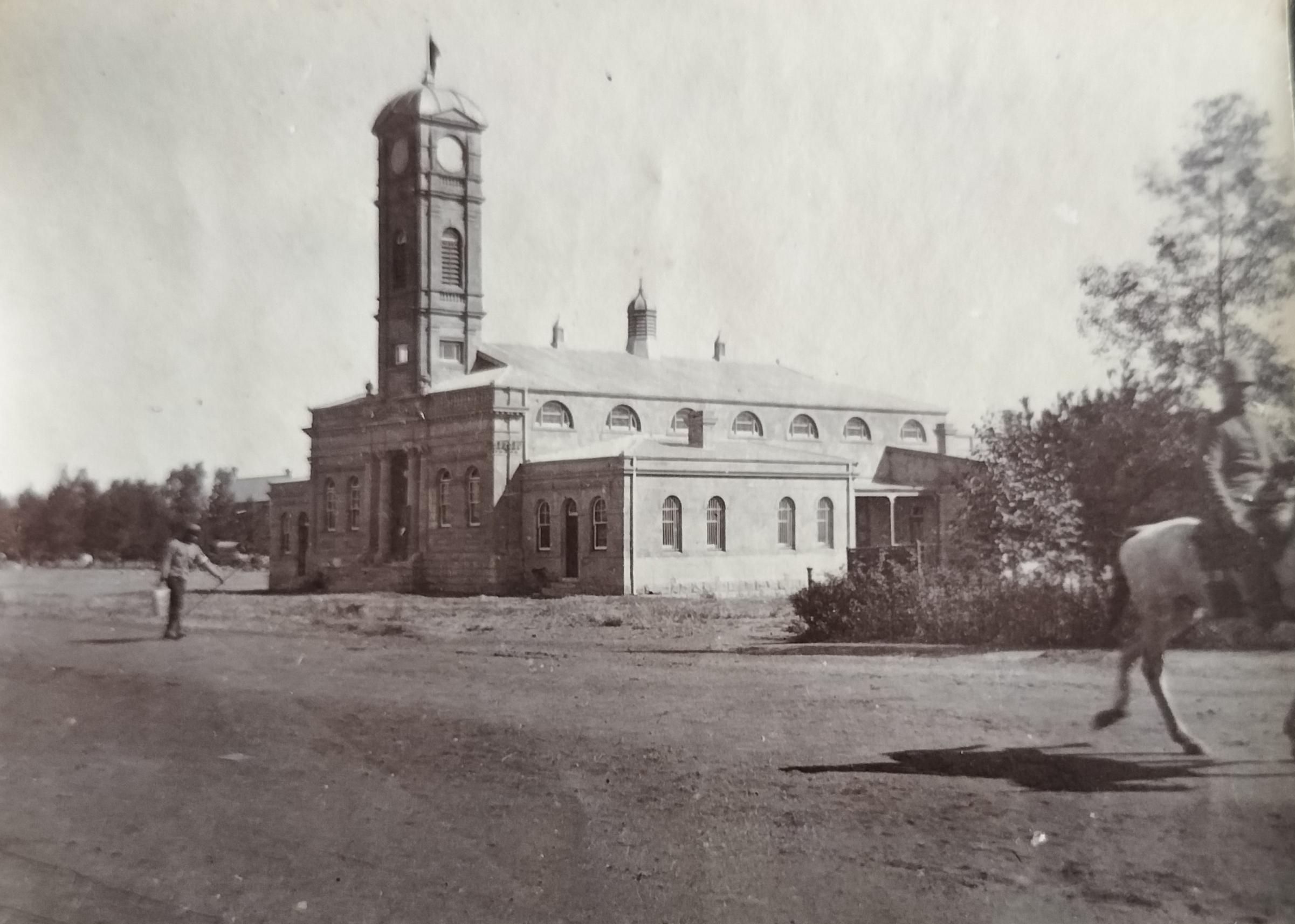

The Newcastle Municipal buildings with the Transvaal flag (Vierkleur) flying on Buller's arrival on 18 May 1900

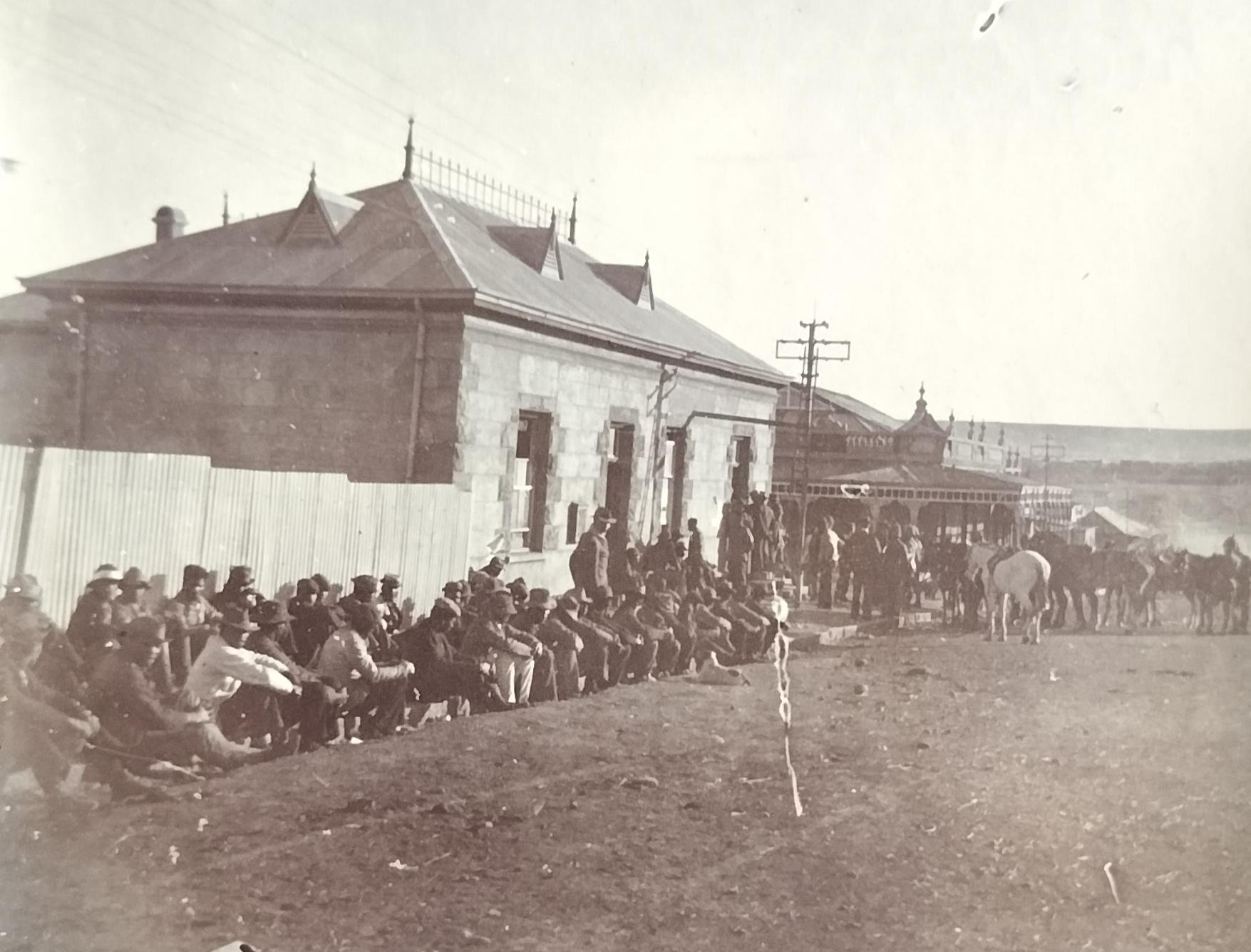

Standerton Magistrate Court where locals are awaiting examination by the Provost Marshall

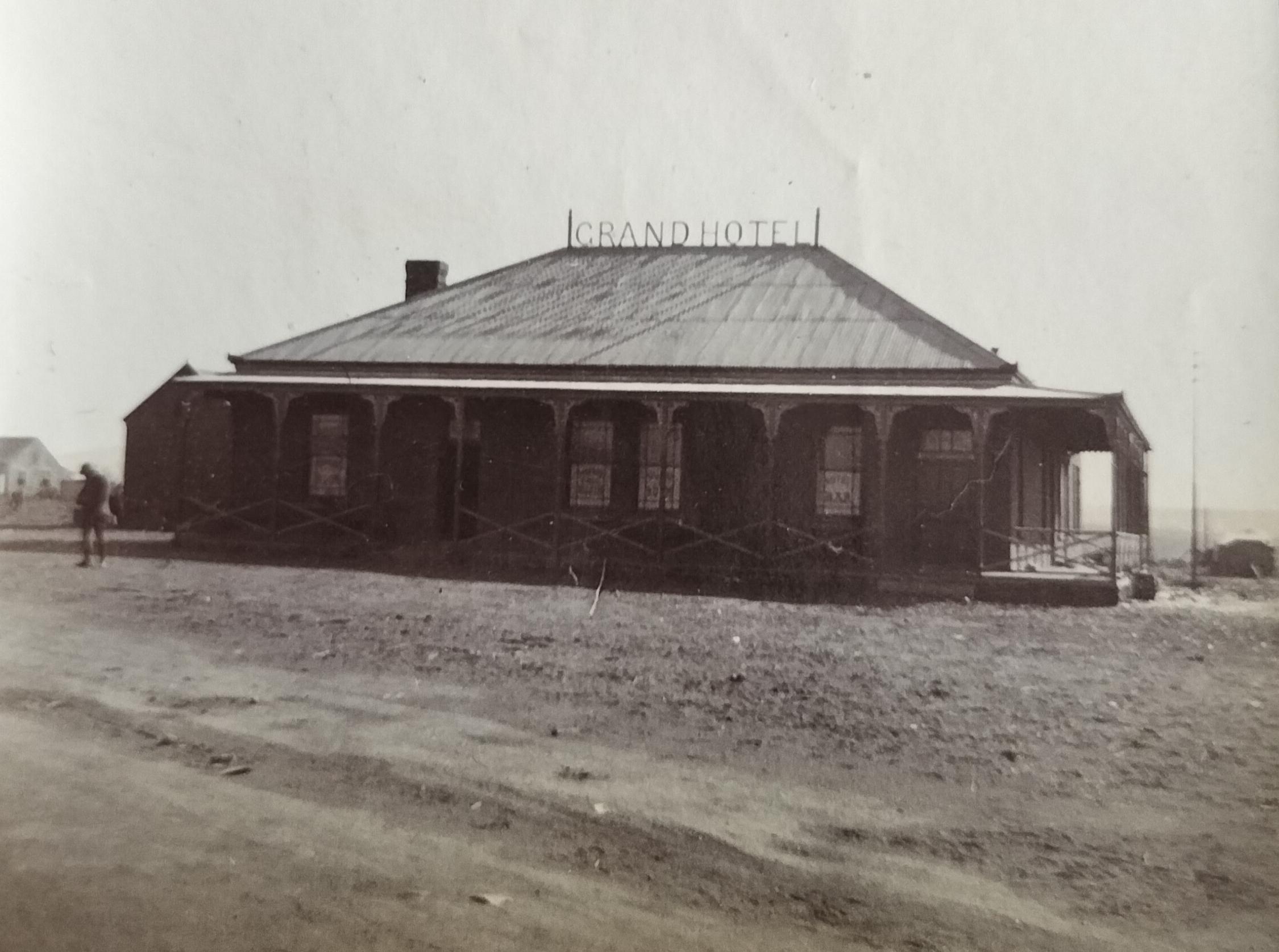

The Grand Hotel in Volksrust

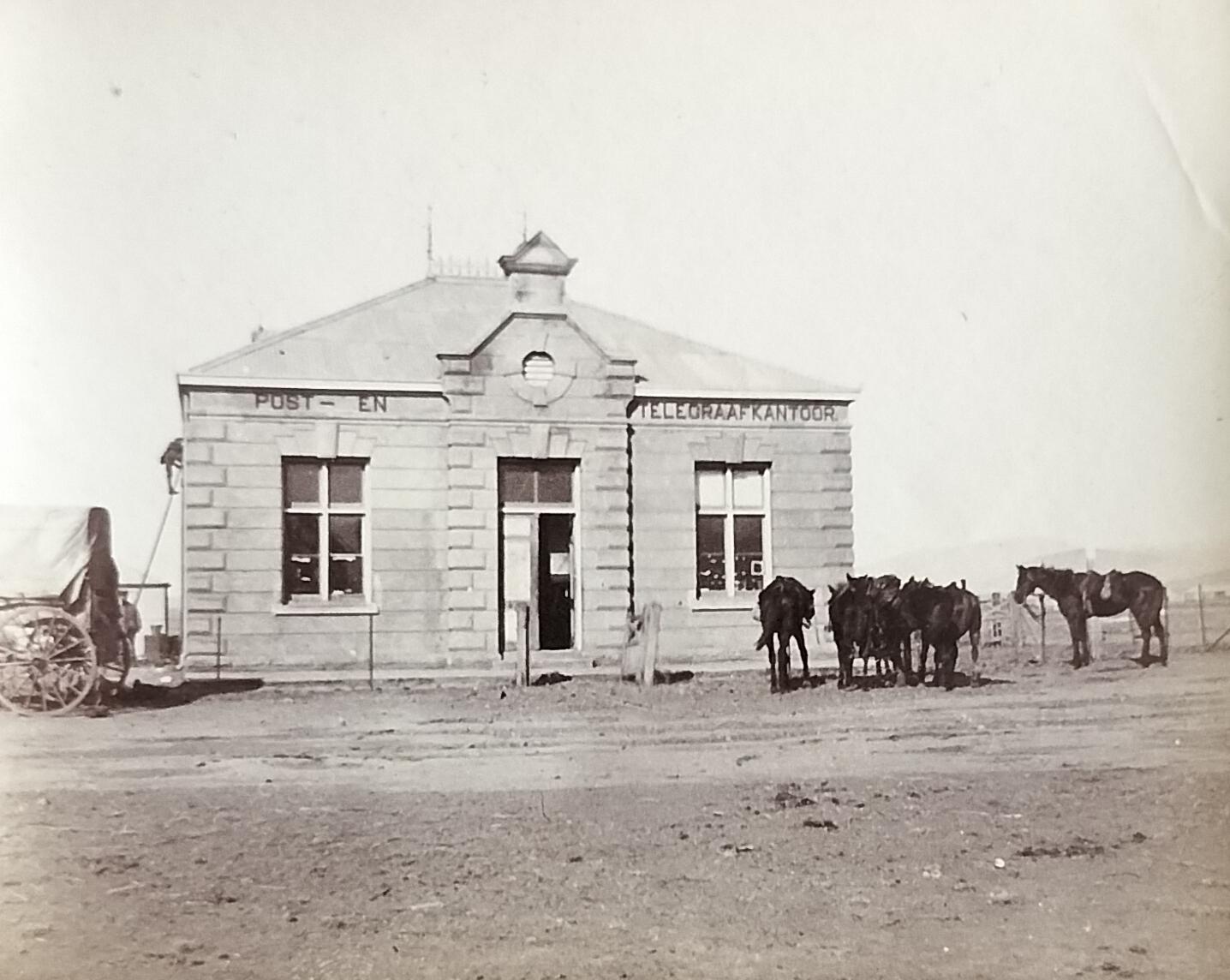

The Volksrust Post Office containing Howie's handwritten notes on the piece of paper on which the photograph was pasted

A close-up of the above photograph

Howie probably carried an elementary Kodak box or bellows camera with him. Whilst his primary role was reporting, he also fulfilled the role of cameraman to support his reporting.

Once the photographs were processed, Howie in all probability had the photographs taken by horse to the nearest railway station to be delivered to his employer. One burning question is, why did he still have the images contained in this article in his possession? It is safe to argue, other than Hansen (2018) - who included some of the Howie images from the Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection in his publication, that this is the first time the images have been published.

Whilst Howie seems to have been travelling with Buller and his men from Ladysmith, the photographic records contained in the cigar box stop at Standerton, in June 1900 in other words.

It is recorded that Buller went on to capture Amersfoort, Ermelo, and Belfast in August 1900, yet the Howie collection contains no photographs thereof. It is therefore assumed that Howie did not follow Buller and his men into Belfast.

Howie, therefore, followed Buller and his men for about 5 months before being withdrawn by his employer or voluntarily electing to step out.

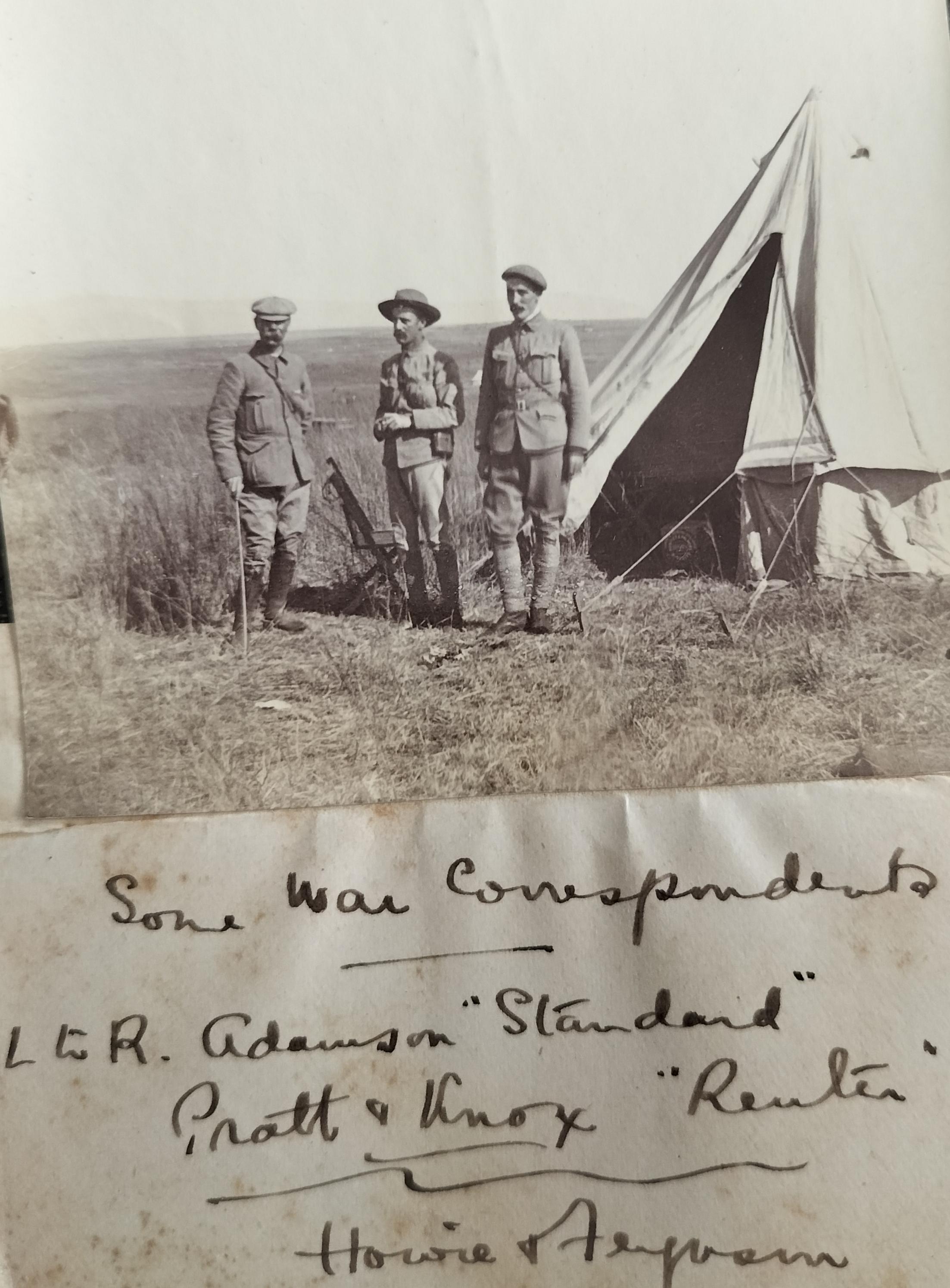

Other war correspondents who appear in the Howie photographs and who have been duly identified are:

- Charles from Daily Telegraph

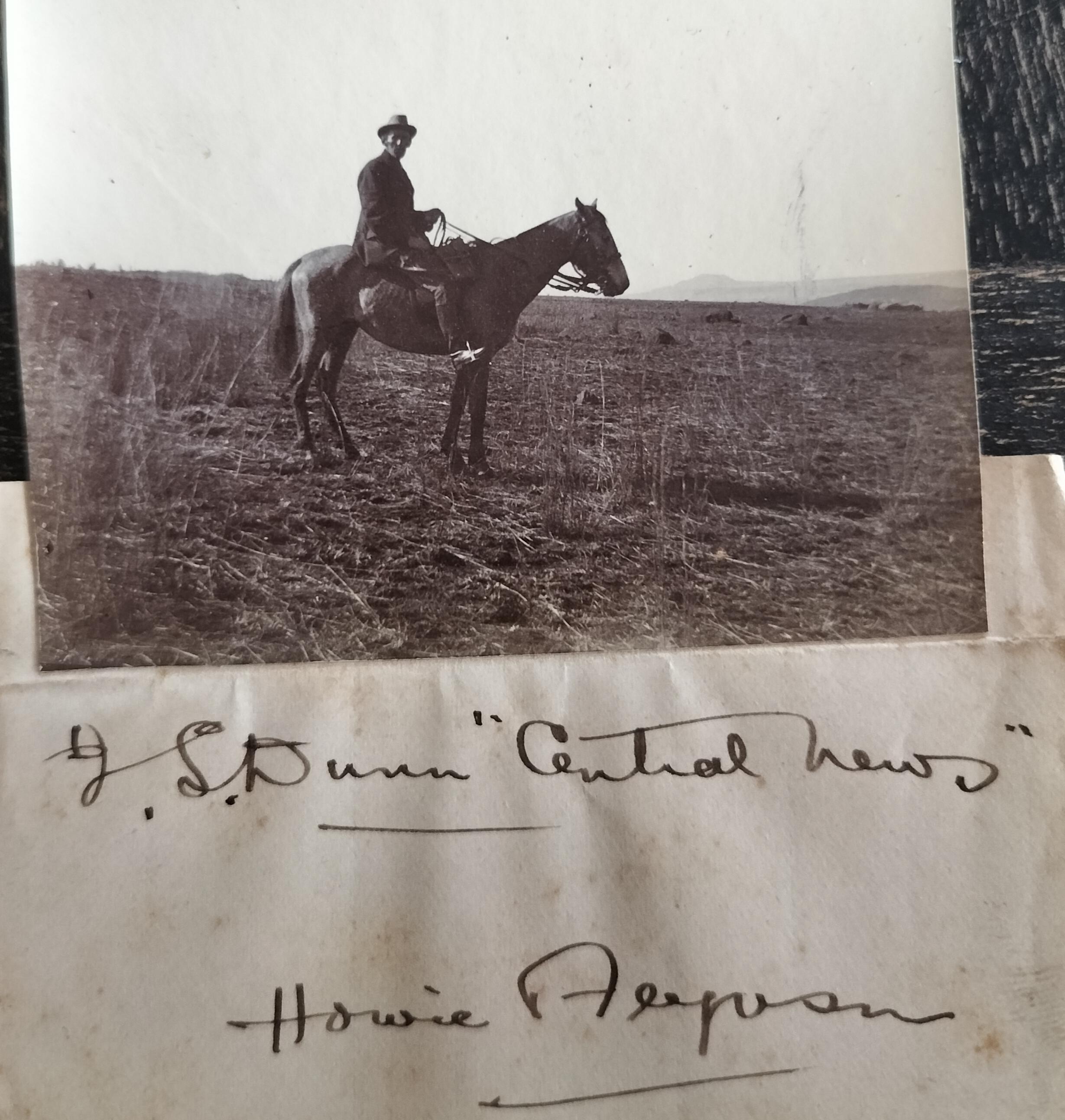

- JS Dunn from Central News

- Meyers & RW Reid from the Natal Witness

- Adamson from The Standard

- WB Knox and Pratt from Reuters

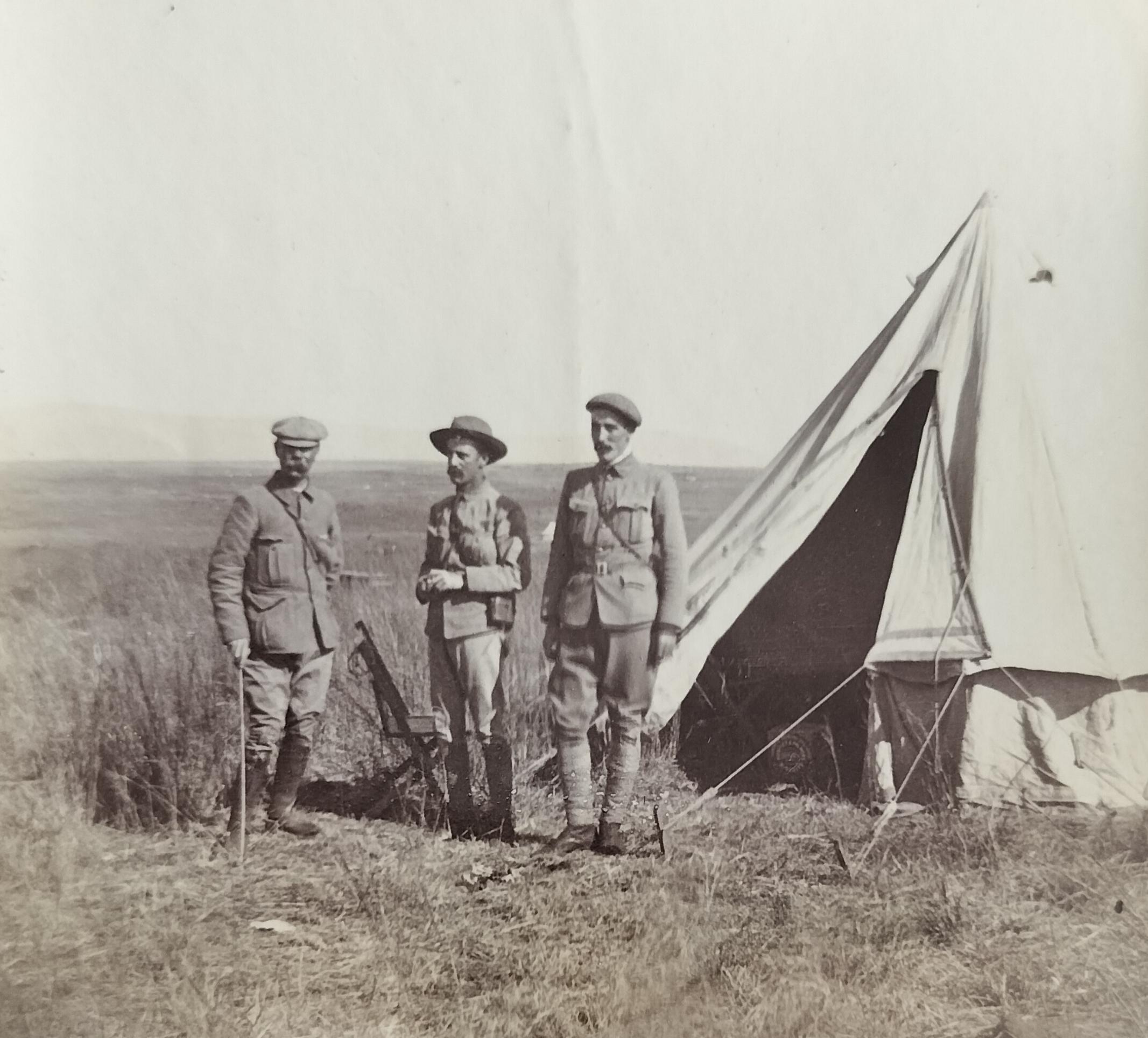

War correspondents following General Redvers Buller and his men during the British advance through Natal between March 1900 and June 1900. From left to right Adamson from "Standard" and Pratt & Knox from "Reuter".

The same image as above showing the photograph stuck to a white piece of paper containing details of the image in Howie's handwriting

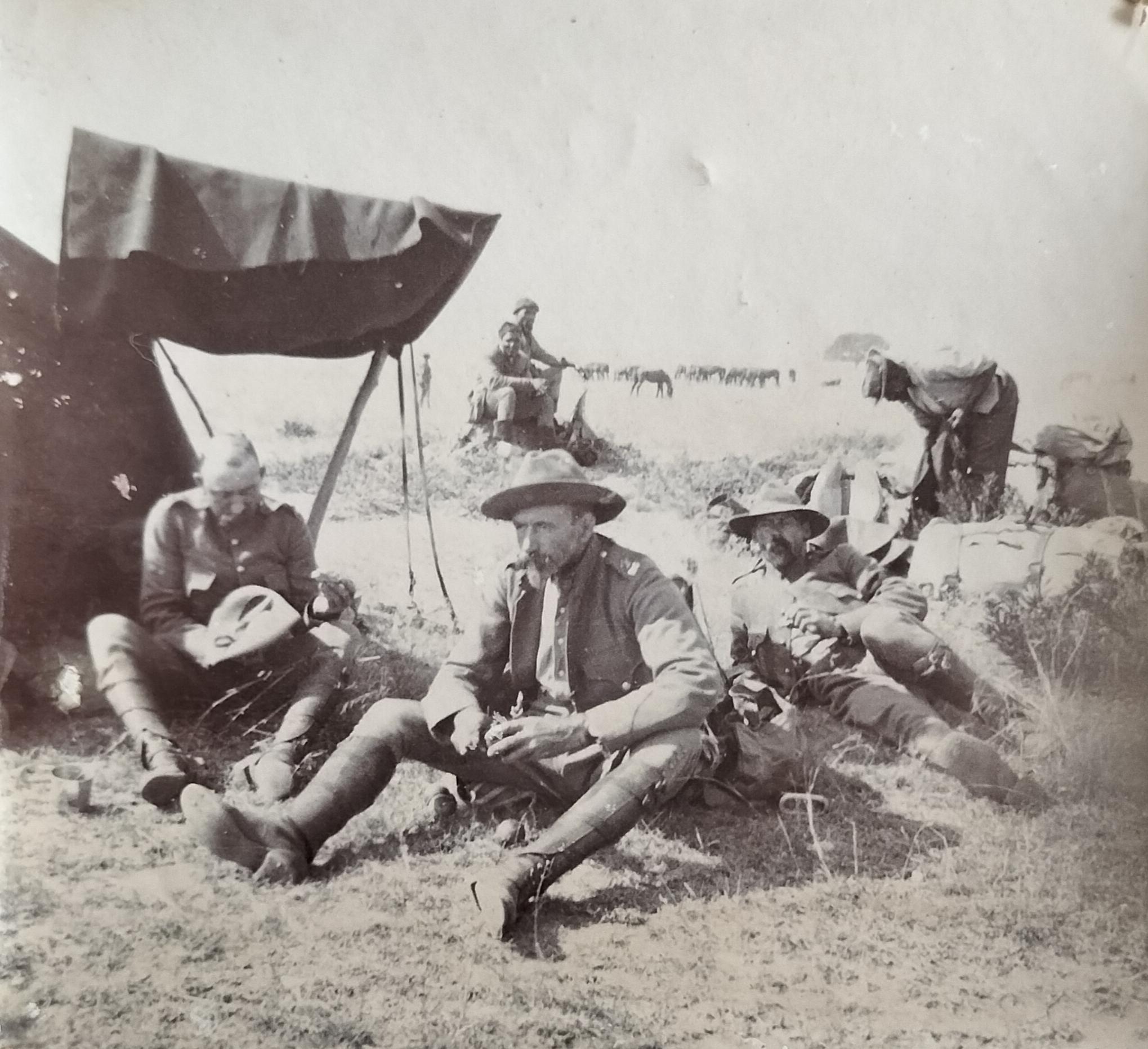

Anglo-Boer War correspondents at lunch. From left to right are Charles from "Daily Telegraph", his assistant Myers and RW Reid from "Natal Witness"

Anglo-Boer War correspondent JS Dunn from "Central News" on horseback

Reference is also made to John Ferguson in some of the photographs, but no information could be obtained about him.

Not all the above journalists have been recorded by McCrachen (2015) in his Anglo-Boer War correspondents list.

Considering the vast number of journalists following Buller, it is clear that the reporting of the events to British citizens was part of the British military strategy.

David Stewart Howie (1875 – 1921)

David Stewart Howie was born in Scotland (Dundee) in 1875. When he arrived in South Africa is not clear, but it is suggested that he may have arrived at the start of the war (1899), aged 24, in that he had built-up work experience as a young man in Scotland prior to his arrival.

After his stint as a war correspondent, he settled in Pretoria where at the age of twenty-six he married a South African maiden, Isobel Elizabeth Mary Roos (born in Ermelo), on 15 November 1901. For this marriage, the local magistrate issued a special license.

Analysing archival records indicates that Howie managed a successful short-hand and typing business which he established in both Pretoria (Mortgage Buildings) and Johannesburg (Raines Building on Government Square and later Greens Building on Commissioner Street) with at least five employees and fifteen typewriters in use at one point. At the Johannesburg-based office, he had a Miss Hanson managing his verbatim reporting business (early 1905).

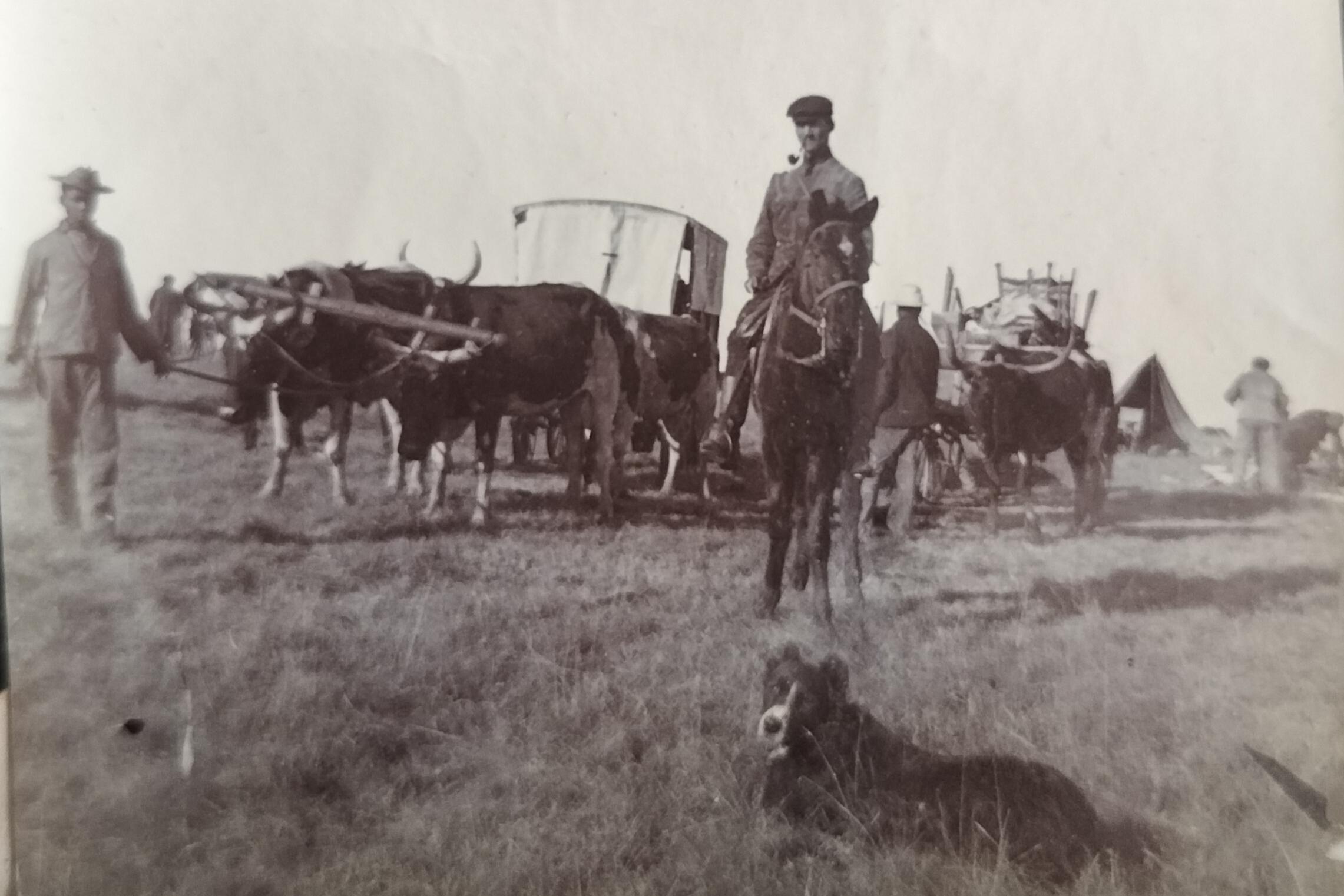

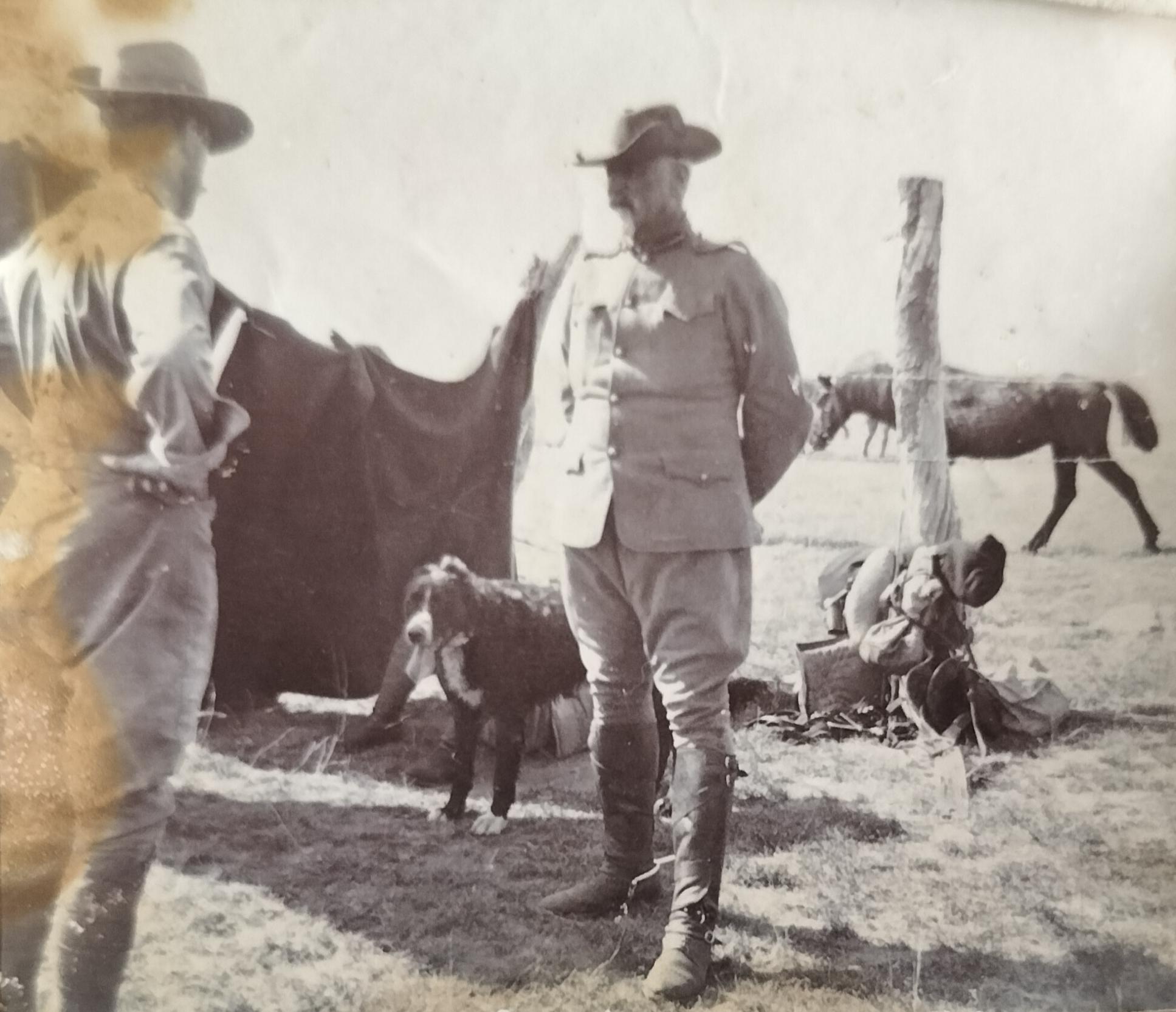

This image is titled: War Correspondents on the move. This is the only known photograph of Howie (on horseback) to have surfaced to date. He was clearly a pipe smoker. The dog can also be seen in other images. It is not known whether the dog was a local farmer's dog visiting the overnight campers or whether it was a travelling companion to the war correspondents.

He did not restrict his work to the Transvaal but also performed work for the Natal and Cape Colony Governments.

Howie clearly had a passion for conducting work as a short-hand and report writer for various commissions established in early South Africa.

It could be determined that he performed work for the following entities:

- On 1 September 1901 Howie was appointed as Secretary and shorthand writer to the Civil Compensation Department in Pretoria;

- In February 1902, Howie applied for the role of official shorthand writer to the court with the Transvaal Law department. In his application, he states that he has wide experience in verbatim notetaking, both for Commissions and for Scottish Courts. He also indicates that he has worked as a shorthand writer for the Transvaal Gold Law Commission and the Witwatersrand Water Supply Commission. In his application, he provides Sir Richard Solomon, the Attorney General at the time, as a reference;

- By August 1902, Howie still did not receive a response to his application following which he addressed a letter to Sir Richard Solomon asking for assistance. From the letter, it is clear that Howie then had already established his own office, seemingly in the Webber & Kennerley Chambers in Pretoria. In response to this letter, he receives a gentle wrap on the knuckles in that it is stated that there are no vacancies and that in the future his letters are to be addressed to the Secretary of the Law department and not the Attorney General;

- The Gold Law Commission (another 5 months) and the Miners Phthisis Commission in 1902;

- In 1903 Howie was employed by the Housing Commission, the Insanitary Area Commission, and the Johannesburg Road Commission to conduct report writing;

- Howie clearly continued doing odd jobs for law departments in the Transvaal in that in July 1903 payment was authorised by the Witwatersrand district court for typing the Crown Prosecutor (Johannesburg) departmental report;

- He was retained by the Johannesburg Town Council for all their shorthand-related work in 1904;

- In the same year (1904), Howie also worked for the Natal Trade Commission, Witwatersrand Water Supply Commission, and the Native Labour Commission;

- Howie was also appointed as Secretary and a shorthand writer for the Occupation Farms Commission.

Conducting work at the Commissions as a private citizen did not go unchallenged. At one point Howie submits a claim of £127.19 to the Commissioner of Native Affairs for his services as a shorthand writer. This resulted in some questions being asked due to the high fee. The appointed Commissioner also questions why a government employee was not allocated to the role.

During the height of his career, an objection also was submitted by Howie’s opposition attempting to prevent Howie from continuing his work (as it relates to shorthand and typewriting) with non-governmental entities whilst (allegedly) holding a remunerated gazetted Government appointment. A brief response from the Government to the complaint however states that Howie was not an appointed civil servant.

Howie’s success did not go without financial challenges in that during 1906 he voluntarily had himself sequestrated. He owed monies, to amongst others, typewriter agencies, newspapers for advertising and a bank overdraft. Indications are that he had at least five people in his employ who he could no longer afford to pay. He was indebted to the value of £1209.5.3 at the time.

Letters held at the South African National Archives, indicate that in 1911 Howie was attached to the Union of South Africa’s Agricultural Department as acting secretary and editor of the SA Agricultural Journal.

During World War 1, Howie was attached to the South African Army Service Corps (Citizen Service), in that in January 1917 a Captain David Stewart Howie was released from his duties. Given his profession, it must be assumed that he was in service of the signal corps.

Howie died at the young age of forty-six on 18 October 1921 in South Africa. The cause of his death is unknown. His wife, Isobel, died aged fifty-nine on 22 October 1938. The couple had six children.

Some Natal Carbineer officers. The Natal Carbineers are the oldest volunteer regiment in the former British Empire. The unit was established on 15 January 1855.

Boer prisoners who were captured at Laing's Nek held by the British at Charlestown

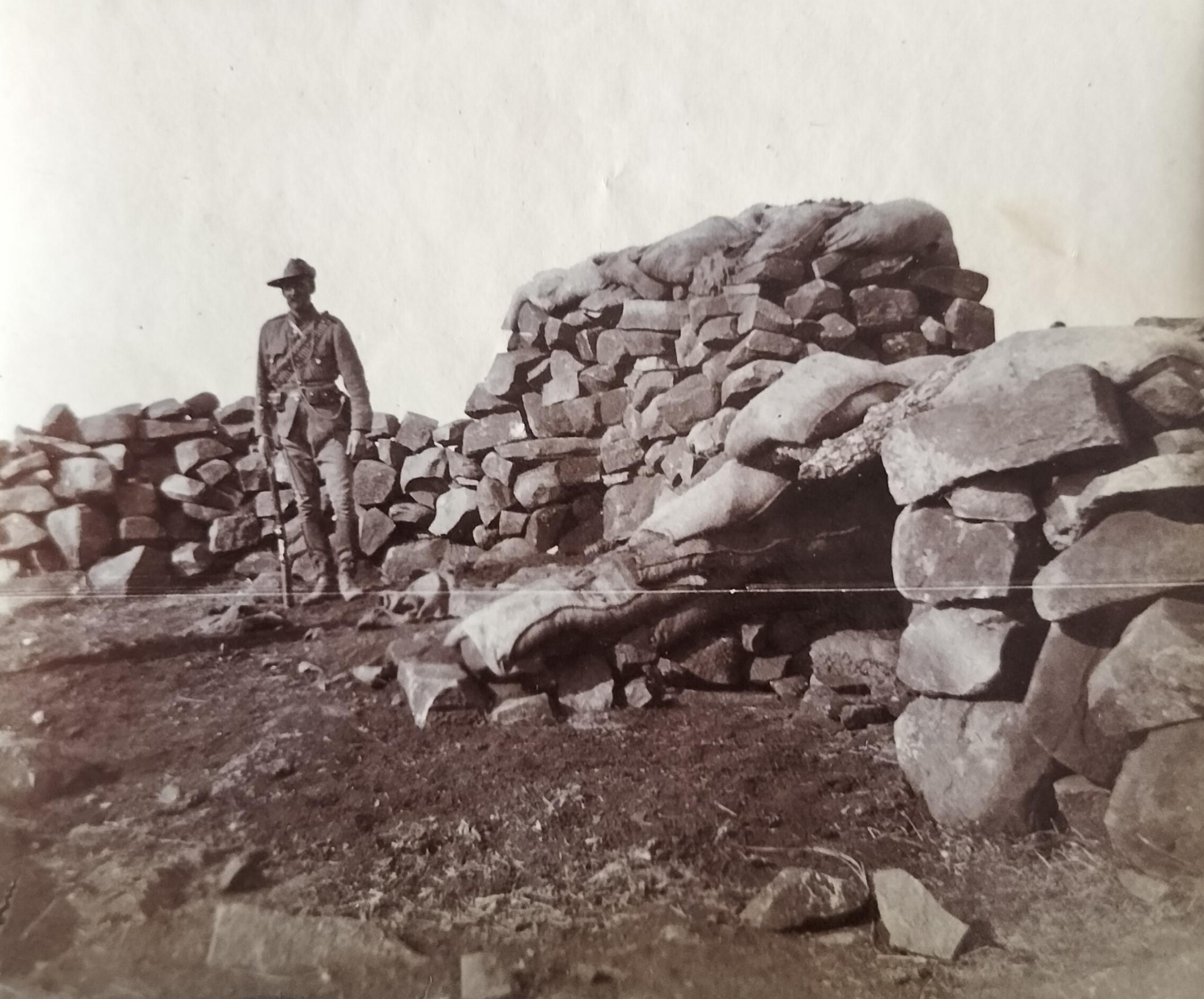

A British soldier standing in a Boer sangar on the top of Helpmekaar Nek where the Boer 15-pounder was placed in the hands of the Natal Carbineers

Brigadier General Johan Dartnel, the Commandant of the Natal Volunteers at Waschbank (near Dundee). The dog also appears in other images contained in the Howie photographic collection.

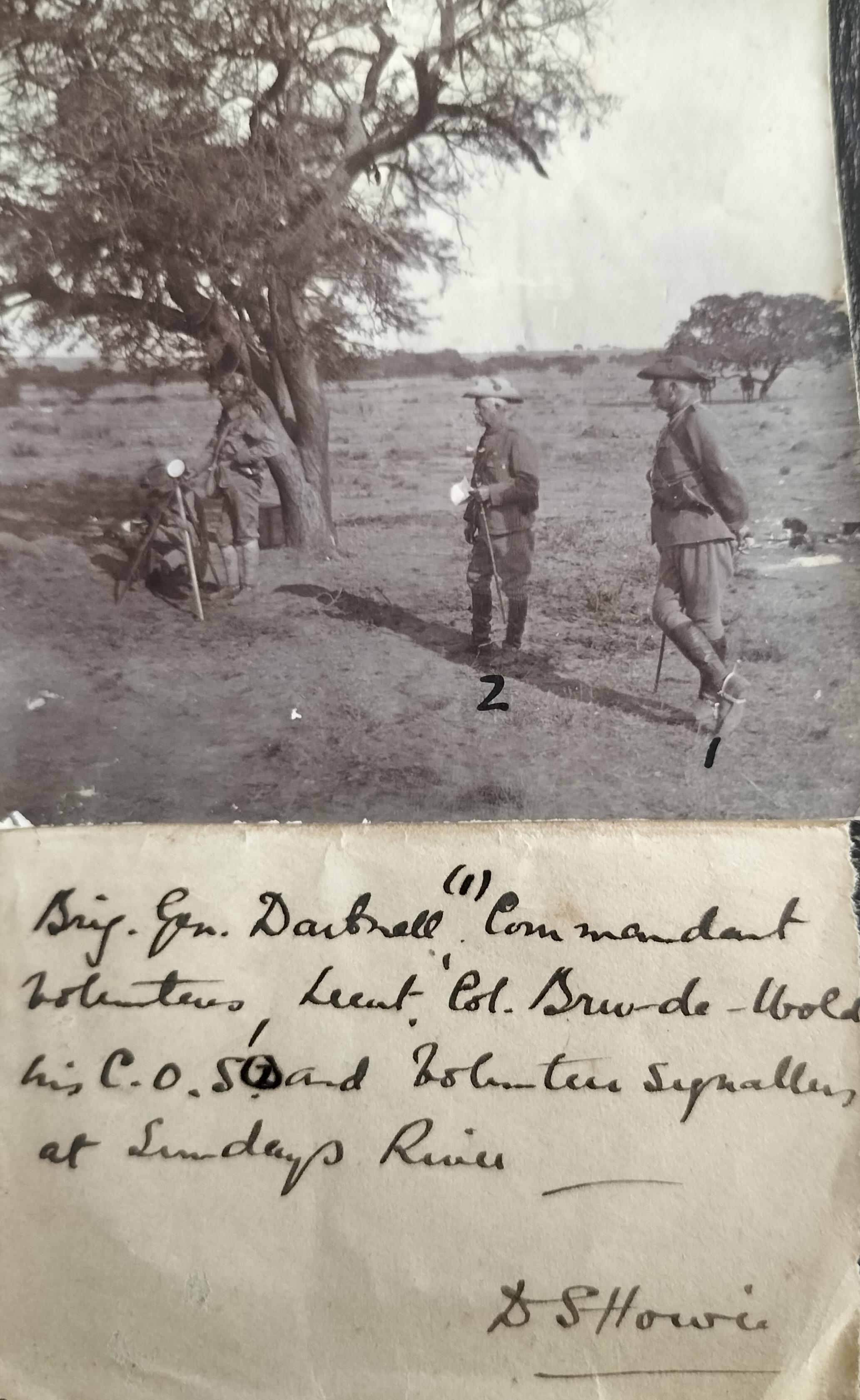

Brigadier General David Dartnell (1), the Commandant of the Natal Volunteers with Lieutenant-Colonel HT Bru-de-Wold, his Chief of Staff (2). Note the Volunteer signaller on the left standing with his heliograph.

The same image as above contains Howie's notes

A Boer ambulance captured at Bothas Pass (between Memel and Newcastle)

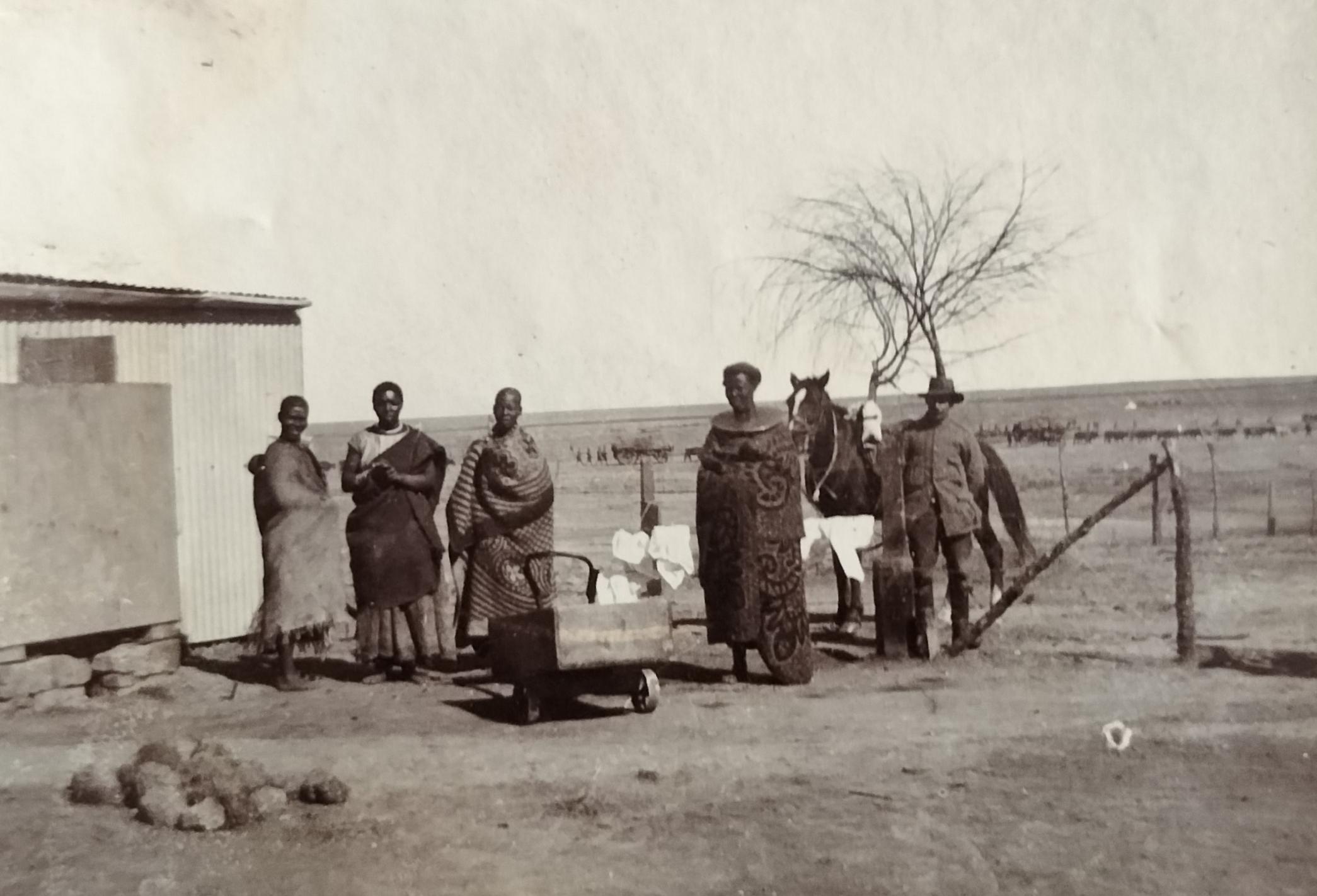

Locals watching as General Buller's column passing their homesteads

Closing

Thanks to photographs contained in a cigar box – photographs I probably would not have found if I had not followed my instinct to open drawers and boxes in search of photographs of interest, the ‘found’ Howie photographs again confirm how existing historical records can be expanded on or refined by relying on photographs to construct a historical narrative of some sort.

The trend in South Africa of ‘rescuing’ vintage and antique photographs is growing. Ten or fifteen years ago, the interest in this old imagery was limited compared to today. This in itself is good news for capturing and curating South African history through the use of photographs.

Sadly, much of the material is still destined for the foreign market.

A week ago, I found a Johannesburg photograph of historical significance. The dealer wanted an exorbitant price for the photograph. I made him an exceptionally decent offer, albeit one-third of what he wanted, to which he responded if he did not get his price locally, the image would go abroad. Could it be argued that this would be a loss to South African heritage?

Whilst he is entitled to price his material as he sees fit, his stance alone opens a Pandora box around selected dealer capitalism (read greed), local versus foreign pricing, or the sensitive topic of high value local material being on offer to the foreign market.

But then, money talks. It is a fact, for example, that the better South African ethno-photographic material from the late 1800s and early 1900s resides in the hands of private collectors abroad. Granted, the images may already have ended up abroad some one hundred years ago and is simply circulating in the hands of collectors, but new material that occasionally surfaces in South Africa fetch exorbitant prices on the international market. I have for example been offered “silly” money by an American for a specific themed collection held in the HPRC (Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection).

About the author: Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources

- Hansen, F. (2018). Indrukke van die Oorlog (1899 – 1902) – ‘n Fotoreis. Friedel Hansen. Pretoria

- Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection

- McCrachen, D.P. (2015) The relationship between British war correspondents in the field and British military intelligence during the Anglo-Boer War. Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 43, No. 1, 2015

- South African National Archives (SANA). Various files as it relates to DS Howie

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.