Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Allen Duff recently published the book The Story of the Millwood / Knysna Goldfield. It tells the story of the rise and decline of the goldfield through the lens of the people who lived and laboured there. We are very excited to publish the first chapter below. Click here to view details of the book.

Gold! Yes, Gold! In the late 19th century the word aroused a range of highly-charged emotions. Undoubtedly the greatest of these emotions was greed. Gold conjured up visions of wealth and grandeur. Gold was an open sesame to a world of prestige, well-being, acknowledgement and pleasure. Thoughts of gold fired the imagination. It roused the noble and the disaffected of society: the energetic and the lethargic alike. Eldorado was seemingly within every man’s grasp. Provided he had the physical and mental stamina to walk to and live in outlandish places like the Canadian Klondike which drew fortune-seekers in their tens of thousands. Gold was a rallying call.

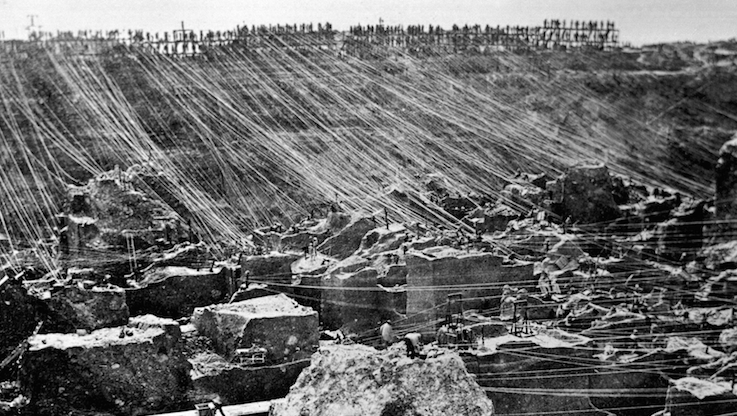

In the 1880s there were rumours about gold emanating from the south-western part of the Cape Colony. Could they be true? Why not? Look at the diamonds which were found in the interior in the 1870s along the river banks. The huge open-cast mine being carved out of ancient volcanic rock at Kimberley. Diamonds and more diamonds! It fired the imagination. And now in the 1880s men spoke of Millwood and gold.

Diamond mining in Kimberley

However, the story does not start at Millwood. It started on the banks of the little-known Karatara River which flows into one of the region’s coastal lakes – the Swartvlei. A few hundred metres north of the junction of the river and the lake, the road from George to Knysna crossed the Karatara river by a causeway. This road was part of the ambitious road building programme introduced by the Governor of the Cape Colony, John Montagu, and the Colony’s surveyor-general, Charles Michell. The father and son engineering combination of Andrew and Thomas Bain had continued with their construction plans which had started in 1867. By the mid-1870s the George – Knysna road had reached Ruigtevlei which is north-east of present-day Sedgefield. In 1875 Thomas Bain appointed a young engineer who had recently immigrated from the USA to supervise the construction and upgrading of further sections. He was Charles Frederick Osborne.

Charles Frederick Osborne was born in London in 1844. In the mid-1860s he sailed to the USA where he became an engineer. He married Elizabeth Wallace who was 18, in 1872 in Boston. Elizabeth's family came from Dublin in Ireland. In the mid-1870s Charles came to the Cape Colony. Perhaps it was the diamond boom centred on Kimberley which attracted him to Southern Africa. However, probably short of money, he took an engineering job with the Cape Colony Government’s Public Works Department. He landed up working under Thomas Bain on the George – Knysna road. Among Charles’ tasks was the excavation of gravel from the banks of the Karatara river and its deposit on the sandy road to create a stable surface with better purchase. While this was in progress, in late 1875, a Ruigtevlei farmer introduced himself to Charles Osborne. He was Johannes Jacobus (Jack) Hooper.

Sometime before this introduction, while Jack was looking for grit for his ostriches, he had found an interesting stone. Jack took it to Knysna and showed it to the apothecary, William Groom, who confirmed it was gold. The nugget weighed nearly an ounce. Jack showed the nugget to his mother's brother, Roelof Pieter Meeding, who said that in 1838 he had picked up a similar "klippie". This stone unfortunately had subsequently been lost.

Jack Hooper showed his nugget to Charles Osborne. He had found the gold nugget on the Karatara river’s bank in the vicinity of the causeway.

Osborne borrowed this nugget from Hooper and sent it to the Cape Colony’s Chief Inspector of Public Works in Cape Town. The colonial administration authorised Osborne to search further, but to limit expenditure to a grant of £100.

Osborne surmised that if there was one nugget, there would be others. Together with Hooper they set about digging a few shafts into the tight-packed alluvial spoil. This gravel was washed in a sluice box which they made over the causeway. Thereafter the gravel so washed was dumped on the road. The draw-back for these two prospectors was that every time a cart or wagon wanted to cross the causeway, they had to move the sluice box to one side.

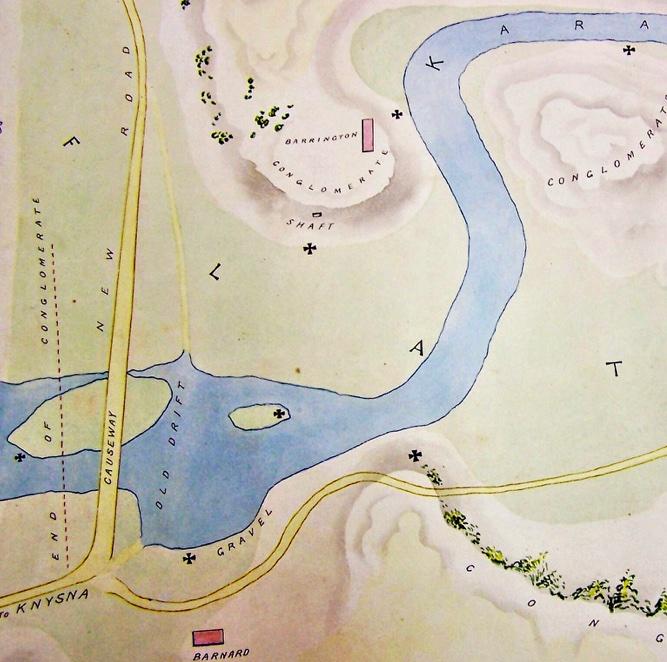

So enthusiastic was Osborne that he produced a detailed coloured map on which he indicated the excavated shafts which they had sunk along the Karatara River. He submitted this map to his employers.

Section of Charles Osbornes map - Karatara River causeway. Crosses indicate shafts.

Osborne claimed to have mining and geological experience – limited as it was to that of his day. The general prevailing theory was that alluvial gold was washed from a quartz reef. Hence find the reef and one had the source.

The nuggets which they found, led Charles Osborne to prospect further north up the river. Charles became totally convinced that payable alluvial and reef gold existed in the Outeniqua Mountains. Travelling by cart loaded with tents and provisions and a gang of hired labourers, Osborne started exploring the wooded hills, creeks and gullies of the farm Hollywood Park between the Karatara and Diep rivers. The results, thought Osborne, were further proof of payable quantities of gold in the foothills of the Outeniqua mountains.

Osborne’s superior, Thomas Bain, was not happy that his department’s employee’s mind and focus appeared not to be on the road - as that of an engineer of the Cape Colony’s administration should have been. Bain was most displeased when he discovered that Osborne was washing excavated gravel in the sluice box before transporting it to improve the surface of the road through the Ruigtevlei. This time-consuming labour-intensive practice translated into a financial expense for Bain’s Department and retarded the road.

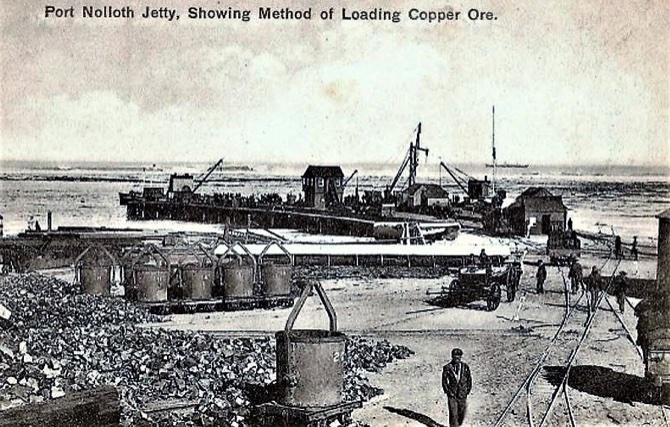

These concerns probably explain why Osborne was instructed to move his base camp from the Karatara river to Belvidere on the eastern bank of the Knysna river. Convinced that Charles’ obsession was detracting from his work efficiency, Bain then organised for Osborne to be transferred in 1877 to Port Nolloth - near the Colony’s northern border on the west coast. Osborne was to supervise the construction of a jetty which was being built at Port Nolloth to expedite copper exports from the Cape Colony’s Namaqualand copper mines.

Old postcard of Port Nolloth Jetty

Perhaps Osborne’s transfer was simply because an engineer was needed for the breakwater’s construction and Charles was young and energetic. Perhaps there was truth in all these reasons.

About a year later the British administration of the Natal Colony became alarmed by a possible Zulu invasion which would threaten the security of Port Natal. Consequently the Cape Colony was asked to provide someone with engineering expertise to assist with the construction of fortifications. Osborne was then dispatched to Durban from Port Nolloth in 1878.

Meanwhile Thomas Kitto, a practical miner, was despatched by the colonial administration to conduct an inspection of the Southern Cape’s gold prospects. His report appeared in the Government Gazette on 03.01.1879. It did not add much to available data. Kitto’s investigative time in the areas of the Great Zwart/Hoogekraal and Karatara rivers was hampered by an extended period of wind and heavy rain. In 1880 E J Dunn, the government geologist, made a favourable report.

Concurrent with Kitto’s and Dunn’s findings were reports of positive finds by some prospectors like Matt Adams, Bean and Lotz in the Southern Cape press. This caused a minor rush to the Karatara area and the odd public mining company was formed. John Barrington Junior was appointed Gold Commissioner.

Bean, being a man of independent means, returned to England [probably in 1879] to float a company. He had half an ounce of alluvial gold. He appeared to have every intention of returning, but while in England he abruptly ended his life by suicide.

Matt Adams was a land surveyor by profession. Since December 1879 he had been the owner of the beautiful estate of Fancourt [at Blanco west of George] which he sold to Ernest Montagu White in 1903. Matt Adams had led an adventurous life having been a digger on the Ballarat and Bendigo goldfields in Victoria, Australia. He had dug a deep shaft adjacent to a river, but finding the work arduous and expenses amounting to hundreds of pounds, he decided that it would be prudent to stick to his profession.

The prospectors who came into the Southern Cape lacked knowledge and experience. Most quickly drifted away sadly disillusioned. Gold was sometimes found, but not in payable quantities. A letter in the George & Knysna Herald newspaper stated that some acknowledged that every ounce of gold found cost £10 or £20 or £26 – even £50 – and gold then was £3.5.0 an ounce. The terrain in the forests and creeks was rough and the vegetation prolific which made access arduous. From time to time a few optimists trickled in, but disillusion soon again occurred.

After the defeat of the Zulus, Osborne in 1880, took extended leave and visited the Lydenburg and De Kaap goldfields in the eastern Transvaal. Osborne’s trek through this area resulted on his return in the publication in 1884 of a booklet entitled South African Gold Fields – machinery to work them.

His experiences in the Transvaal clearly rekindled his contention that the Southern Cape was a goldfield development waiting to happen. His enthusiasm aroused anew, Charles Osborne resigned from his Cape Colony employment and returned to Knysna in October 1885 with the intention of further exploration for gold.

Jack Hooper joined Osborne and they returned to the site of the original find adjacent to the Karatara river. Seven shafts – 3m to 9m – were sunk. Gold was found though how much is unknown. The collapse of another shaft of 24m was catastrophic for their endeavours. After six months and expenditure of about £600 the only definitive conclusion was that alluvial gold didn’t give a profit. The two men parted company. Osborne went on prospecting to the north-east. His extensive prospecting ultimately focused his exploration and that of other men, on certain areas east of the Homtini river. This area was along a tributary named Millwood Creek.

The area was called Millwood as the Thesen family had built a water-driven sawmill there. The rough-sawn timber was hauled to the Passes road by oxen and sleighs. This path climbed the Portland Heights ridge to the south of the mill before descending to the George – Knysna road. Some of the early prospectors used this route.

Thesen’s Millwood sawmill in the mid-1880s. Steam-driven saws in Knysna later made sawing there more feasible and economical: the Millwood sawmill was closed in the mid-1900s.

The remains of the Millwood saw-mill’s water-wheel

In March 1886 Osborne having recovered an ounce of alluvial gold, travelled to Cape Town to request the administration to proclaim Millwood a goldfield. This would have allowed pegging. [This was a few months ahead of the proclamation of certain Witwatersrand farms as public goldfields.] Osborne reported that the occurrence of gold was not concentrated but scattered. “Now this fact”- states the report which he issued – “while on the one hand rendering the country unsuitable for a poor man’s digging, necessitates on the other a special system of working in order that the gold might be extracted profitably … there is little likelihood of a poor man’s diggings being found … to ensure success … companies and individuals possessing the requisite capital” will be needed. Osborne’s usage of the phrase “unsuitable for a poor man’s diggings” clearly stayed with the hierarchy of the Cape Colony’s administration and contributed to the powers-that-be desisting from a hasty proclamation of a mining field in terms of the Minerals Act of 1883.

En route to Cape Town, Osborne had called on Hooper and given him a glowing account of Millwood’s future. Within a week Hooper was at Millwood with sluice-boxes, provisions and twelve labourers. The only other prospector then there was Franzen. [He was a Norwegian who managed the Thesen’s saw-mill].

Hopper found the area a wilderness overgrown with trees, rank vegetation and a mass of dense scrub 4m to 6m in height and so impenetrable that it took a week to clear a path to the location on the river where he had decided to base his endeavours.

No sooner had Osborne’s report been published than a rush driven by feverish excitement and high hopes began. Diggers regularly augmented the mining camp’s numbers. Ongoing reports of encouraging finds appeared in the Press. The Carruthers brothers unearthed a ½ ounce nugget which brought their month’s recovery to three ounces. At £3.5.0 per ounce this recovery was less than expenses, but the prospect of better fortunes outweighed the economics of the activity.

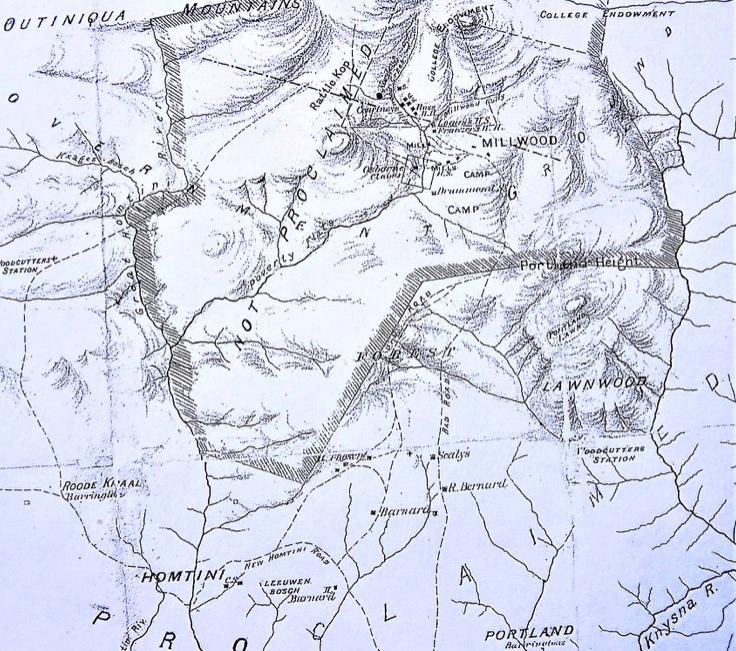

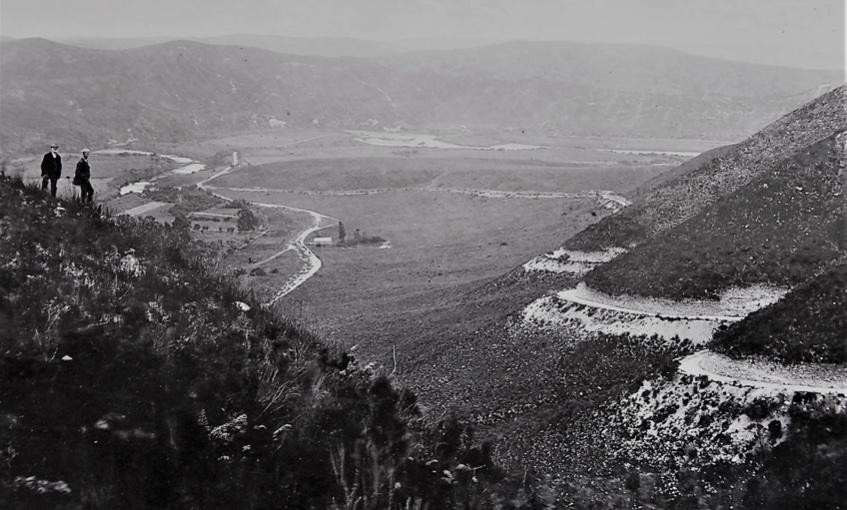

The route to Millwood was not easy to say the least. One must remember that in the 1880s most folk walked rather than rode from place to place. The Passes road from Knysna was arduous. In mid-1886 Ovendon Collard [a Cape Town based civil engineer and surveyor] visited the area. In early August he published a Guide Book to the Knysna Goldfields (Millwood). He informed would-be fortune-seekers that “the route from Knysna to the outskirts of the forest first passes for some distance along the east side of the Knysna estuary. It then crosses the Knysna river over the causeway” [drift] [usually submerged large flat stones formed the road-way] “which is always passable except for about an hour and a half at high water.” Then followed a hard slog up the Phantom Pass. [Not the present road which has a moderate gradient throughout and was completed by Thomas Bain in 1889. The original road climbed the kloof steeply on the northern side.]

From the pass the road went north “through Mr Barrington’s [Portland] estate... past Sealy’s. Continue on the main George Town road until the turning by Barnard’s is reached.” [Before the introduction of signposts, the surnames of landowners were used as landmarks.]

Section from Ovendon Collards July 1886 map

“Having arrived at the outside of the forest, the traveller will find absolutely no accommodation beyond a small shop: sleeping accommodation – none. It will be necessary to arrange a journey so as to arrive at the outskirts of the forest in time to get to Millwood before dark which will be reached in about two hours.” The approach from the Knysna – George Passes road was a Hobson’s choice. There was no road – only paths. There were two possible routes. One was the Thesen path – by which oxen and sleighs hauled timber from their Millwood sawmill. The other was a route a little further west of the Thesen path. It was a route based on a collection of paths made by the woodcutters.

One prospector described the route thus. “It is an abominable piece of torture alike to man and beast … In fine weather it is bad enough, but in wet weather anything more horrible in the shape of paths is scarcely possible and as it usually rains two days out of seven, the results of heavy traffic over loose soft soil, in which the roots of trees are liberally interspersed, can be imagined … It had rained for two days preceding our passage and the path … was simply a quagmire with mud a foot or so deep.”

Most of the early Millwood fortune-seekers walked from Knysna. However, if one had five shillings to spare one could buy a seat in a cart with 9kg free luggage to Walker & Berg’s store at Balmoral from where the two hours plus footslog awaited. Most of the diggers were ill-prepared for the conditions which prevailed. Many had no kind of shelter and thus suffered from cold and hunger. However, if one had money to spare, Collard continued: “At Millwood there will be no difficulty on ordinary occasions in getting accommodation at Logan’s Hotel, Mills Hotel or Ross’s Boarding House. … A road is being made by the Government which when completed, will permit carts to go through to Millwood.”

The Cape Colony government which was afraid of misleading the public with an unproved field, had initially decided not to acquiesce to Osborne’s request, but eventually agreed to allow a search for gold on the understanding that the prospectors would have no legal rights to the land.

At Millwood the fortune-seekers found confusion and a haphazard situation. It was not until the formation of a Diggers Committee at the end of May 1886 that there was some order and procedure. The equipment of these rather happy-go-lucky men was rudimentary. As was their knowledge of alluvial recovery. Many of the sluice boxes were poorly constructed and considerable fine gold was therefore lost.

One of these Eldorado-driven fortune-seekers was Charles Bain from Beaufort-West. His story well illustrates the circumstances of the Millwood goldfield in 1886.

About the author: Allen's interest in Millwood started in the mid-1960s when in his university vacations he worked for the Port Elizabeth municipality. In his lunch hour he read 19th century newspapers in the nearby city library archives. It was here that his interest in Millwood was kindled. After 28 years on the academic and administrative staff of Michaelhouse [KZN], he took early retirement. He and his wife translocated to George where they operated an accommodation business for 20 years. The archives of the George museum and his proximity to Millwood, enabled its history to crafted and published.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.