Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Below are a few excerpts from the report on the restoration of the town of Wupperthal following the tragic 2019 fire. Many commentators have described the fire as the worst disaster to South Africa's built heritage since the 1969 Tulbagh earthquake. The project shows what can be achieved when architects, contractors, funders and the community pull together for a greater cause. Click here to view the full report.

Historical Background

The mission station of Wupperthal is a veritable time capsule. It is located within the arid Cedarberg region of South Africa, a place characterized by craggy wilderness landscapes and spectacular seasonal displays of wild flowers which have drawn and captivated many over the years: from the celebrated poet, medical doctor and epicure, C Louis Leipoldt in the earlier 1900’s, to modern day international rock climbers and those simply seeking a temporary break from their hectic city lives.

Wupperthal was established in 1830 as the first Rhenish mission station in South Africa. The new settlement was spearheaded by the missionaries Baron Theobald von Wurmb and Louis Leipoldt’s grandfather, Gottlieb Leipoldt. The mission was laid out on the farms Rietmond and Koudeberg, situated in the isolated but fertile Tra Tra River valley approximately 72km from Clanwilliam and about 250 km from Cape Town, after the farms were acquired by the Rhenish Mission Society. Interestingly, the founding of this mission town pre-dated, by approximately 100 years, the formal founding of its namesake in Germany.

By 1834 a church and school had been built to serve the local population that soon came to include freed slaves from surrounding farms and dispersed Khoe San that had survived an earlier devastating smallpox epidemic at the Cape. Gottlieb Leipoldt initially used what was almost certainly the original Rietmond farmhouse as the first parsonage. It was from its semi-circular front stoep that open air church services seem to have been held until the completion of the settlement’s church building. The old farmhouse was subsequently named Leipoldt House in his honour.

The mission station expanded rapidly and by the 1850’s, the town centre, or ‘kerkwerf’ included a new parsonage, new school buildings, a tannery and a small shoe factory. Rev. Leipoldt, who was also a qualified cobbler, provided the instruction. The residential portion of the village, comprising terraces of thatched houses, grew up against the hillside to the northeast of the town centre. In 1965, the mission settlement was formally taken over by the Moravian Church after the Rhenish Mission Society left South Africa.

The Fire

On 30 December 2018 at the height of summer, a disastrous fire broke out at the base of the pass entering the town after some local residents tried to smoke out a beehive for honey. The hive was in a tree surrounded by tinder dry underbrush while a strong wind was prevailing. The fire, assisted by the wind and dry leaves soon became uncontrollable. It spread, splitting in two directions where it gutted a substantial number of buildings in the town centre and turned 52 houses within the residential area into blackened shells.

The fire was not only disastrous for the historic fabric of the town, but also the community, resulting in one fatality and approximately 200 destitute, homeless people. The settlement’s brass band, a social focus of village life in this isolated part of the world, lost all of its brass instruments which had been stored in the Community Hall, one of the buildings gutted. So bad was the damage to both the town and its residents that the cataclysm came to be regarded as the worst disaster to built heritage since the 1969 earthquake that struck the historic town of Tulbagh in the Western Cape.

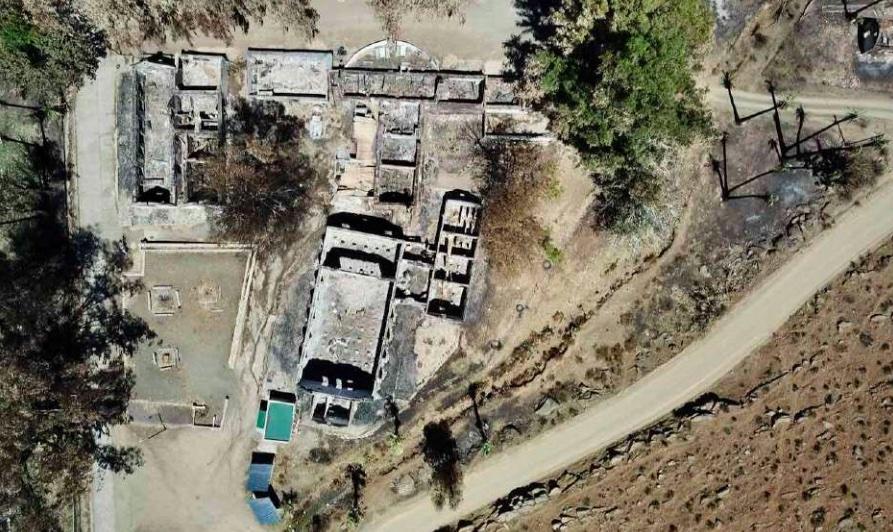

Aerial view showing the gutted state of some of the buildings in the town centre after the fire. Top centre are the remains of Leipoldt House with its T-shaped plan and semicircular stoep. To the left are the remains of the old Mission Stores building, the first school building in the settlement. Below are the remains of the Community Hall. The Old Blacksmith’s Shop (Smitswinkel) where wagon wheels were repaired after a torturous trip down the mountain pass is just visible on the extreme upper right. The latter was the first building to be gutted in the fire. The road on the bottom right enters Wupperthal from the pass. (Drone image: Goal Zero Consulting).

To make matters worse, most of the severely damaged buildings had either been underinsured or not insured at all. Initial structural engineer’s reports were that the gutted buildings were now structurally dangerous and would have to be demolished. There were also rumours that demolition teams were preparing to demolish these severely damaged structures.

Action immediately after the fire

Various private and public bodies were quick to react despite the disaster having occurred during the festive season holidays. Amongst those were Gift of the Givers who donated a substantial amount towards the reconstruction of the settlement's gutted houses; Heritage Western Cape who dispatched a team to assess the damage that included some of its Council members; the Vernacular Architecture Society of South Africa, Cape Institute for Architecture (CIfA) and various individual donors. CIfA set up a team of volunteer members to assist, free of charge, in preparing the drawings required for the reconstruction of the gutted houses. The Provincial Department of Human Settlements arranged for temporary housing to be erected on the town’s sports field for those now rendered homeless, although that took much longer to implement.

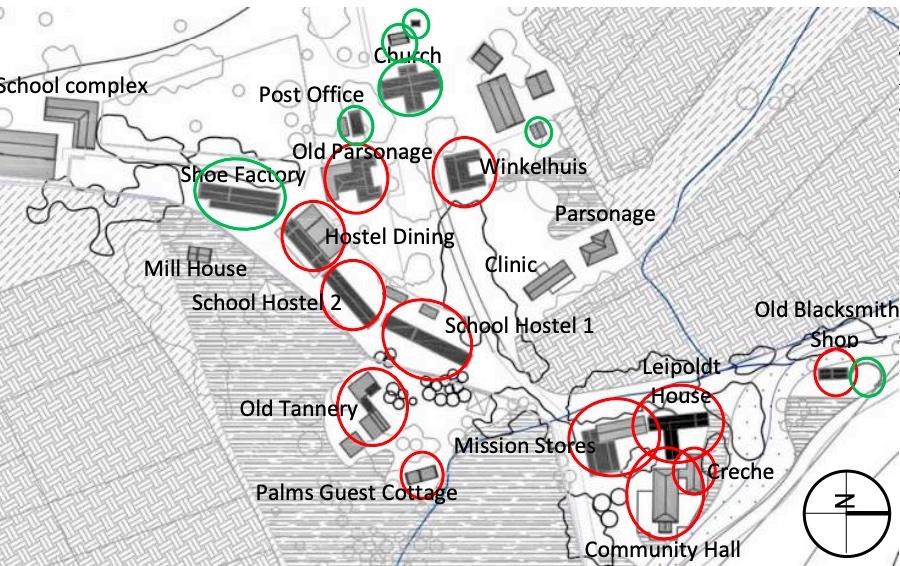

Site plan of the Wupperthal town centre with buildings gutted by fire circled in red. Other buildings where significant refurbishments were done are circled in green. The church and shoe factory were miraculously not burned. (Base diagram; TV3 Architects & Planner)

The fire gutted ‘Winkelhuis’ (Shopkeeper’s House) after the fire. The building had been the administration headquarters for the town before the fire. This image is typical of the degree of damage sustained. (Image: ARCON, 24 January 2019).

By far the most significant contribution was from the Rupert Foundation. That transpired after the industrialist Johann Rupert, son of the late Dr Anton Rupert who had been largely instrumental in the restoration of Church Street, Tulbagh, in the wake of the 1969 earthquake, offered to assist. The Rupert Foundation (hereafter ‘the Foundation’) was ultimately to fund almost the entire rescue restoration works within the town centre and, thereafter, much of the reconstruction work to the fire damaged houses. This was especially significant as approximately 80% of the residents are reliant on one or other form of state welfare grant.

A Stellenbosch firm of architects and planners was engaged to prepare the documentation for the rescue restoration work to the town centre and I was brought in to assist as the architectural heritage consultant. A Cape Town based firm of structural engineers was specially selected for the project based on their experience in working on historic buildings to ensure that as much historic fabric as possible would be retained without compromising public safety. A Worcester based building contractor won the tender to undertake the work. Site handover occurred in early July 2019 despite delays caused by the COVID epidemic and after heritage and local authority approvals were in place.

Prior to work commencing, plastic damp proof sheeting was tied over all soft sundried clay brick wall caps that had been exposed by the fire. That was to prevent saturation by impending winter rains that would otherwise likely have led to wall collapses. Furthermore, and with guidance from Heritage Western Cape, the ashes and rubble of each of the buildings was carefully sifted for historic ironmongery and other surviving period features. All recovered items were numbered and bagged for re-installation, wherever possible, as part of the reconstruction process that lay ahead; all in accordance with the buildings from which they had been retrieved.

It was agreed with the Moravian Church that restoration works would commence with the Community Hall, Creche and Mission Stores buildings as best addressing community needs.

Examples of historic ironmongery recovered after the fire. These included a large 19th C front door lock (bottom left). Most were recovered from the ashes and rubble of the Winkelhuis; and most, including the badly damaged and heat-seized door locks, were able to be reconditioned and reinstalled during the restoration project. (Image: ARCON, 24 January 2019)

Click here to download the full report which includes details of the individual buildings restored during the project.

Main image: Exterior of Leipoldt House after the fire. This building is most probably the original Rietmond farmhouse, pre-dating the arrival of the Rhenish missionaries by about 30 years. The uncharacteristic semicircular stoep appears to have been used as a podium from which open air services were conducted before the church was completed, explaining its non-traditional shape. (Image: ARCON, 25 October 2019).

About the author: Graham has been involved in architectural heritage and cultural landscape projects since 1986 when he obtained his Master's degree in Conservation (Built Environment) from the Institute of Advanced Architectural Studies, York University, UK. He also holds a Bachelor's degree in Architecture from the University of Cape Town. Over the years, Graham has been involved in significant international, national and provincial heritage projects (click here for more).

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.