Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In the article below, Tony Murray profiles civil engineer John Scott Tucker. The piece first appeared in the publication 'Past Masters: Pioneer Civil Engineers who contributed to the growth and Wealth of South Africa'. Click here to view the stories of other great engineers.

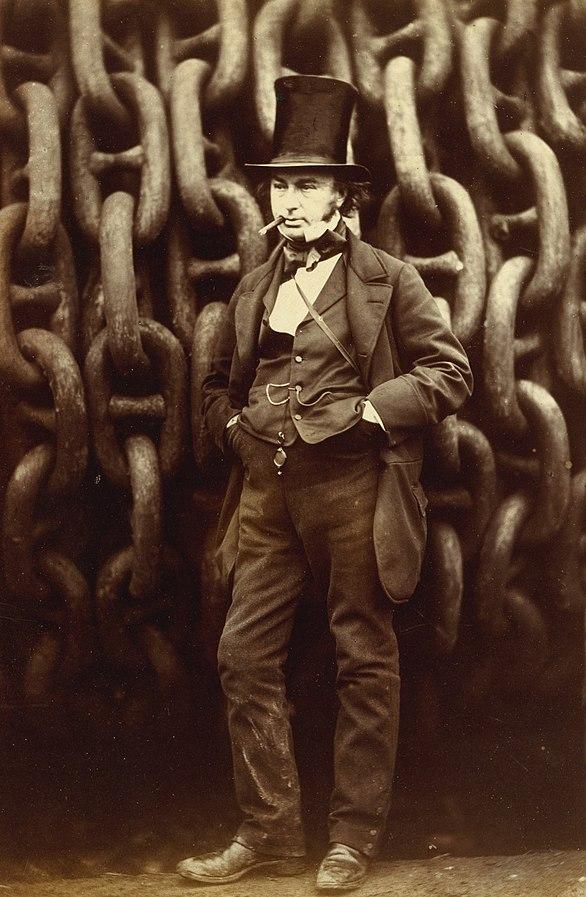

Tucker was born in England in 1812, the son of a naval surveyor. He was in the forefront of the many talented young men who joined the exciting emerging profession of civil engineering, and after being articled to John Rennie and serving his pupillage on the construction of the new London Bridge, gained experience on railway work on the Great Western Railway under I.K. Brunel. Thereafter he was engaged in harbour works in the Azores, Bermuda and Malta, and between 1857 and 1858 he was employed on railway construction in Brazil.

Brunel (Wikipedia)

In 1857 a select committee of the Cape Government met to investigate the construction of a railway to the interior. Tucker, acting on behalf of a consortium of London businessmen, appeared before the committee with a proposal to build a line from Cape Town to Wellington with branch lines to Malmesbury, Wynberg and Stellenbosch. His most important submission was that, in order for the project to be viable, any private railway company should be guaranteed 6% interest on capital by the Colonial Government. The government accepted this proposal, thereby gaining effective control over the operating company and retaining powers to determine the route, design and specifications of the project. However the consortium failed to find the necessary capital, and the concession for a line between Cape Town and Wellington was then given to a rival concern which employed W.G. Brounger as its chief engineer.

Tucker however was not lost to the Cape. He was appointed Colonial Engineer in 1859 and arrived in Cape Town just when work on the railway was about to commence. He immediately took an active interest in the contract and was incensed when the line was extended from Woodstock into the centre of Cape Town without his involvement. He furthermore demanded that the earthworks on the entire line be increased by some 60% at no additional cost. Perhaps his efforts at controlling standards and limiting expenditure were commendable, but Brounger – who was also a very experienced railway engineer – regarded this as unwarranted interference. After further instances of such meddling, Brounger complained to the Colonial Secretary. The upshot was that Tucker's job was redefined to specifically exclude involvement in the railway "on account of his numerous and onerous other duties". He was likewise denied any responsibility for the Table Bay Harbour works which had commenced in 1860.

Tucker's "onerous other duties" proved minimal and he consoled himself by trying to reorganise the office of the Colonial Engineer, which, it was alleged, he had inherited in a state of some disorganisation. However the task proved beyond him, and he eventually recommended that the post of Colonial Engineer be abolished. This was accepted by a Government eager to cut costs, and he returned to England in 1864. Thereafter he undertook consulting work in London, and eventually became Superintendent of Public Works in Barbados – surely a rather trivial post for someone who had once been regarded as a promising engineer.

Tucker's most enduring work while in the Colony was the design of the lighthouse on Robben Island, which still exists (see main image).

In an era of unrest in the Colony and abroad, Tucker founded a corps of engineering volunteers which became known as the Cape Sappers and was incorporated into the Cape Garrison Artillery in 1891.

Like many engineers of his time, Tucker was a talented watercolourist.

He died in Dover in 1882. The obituary in the Proceedings of the ICE gives a final insight into the character of this unfortunate underachiever. It states that Tucker was a competent engineer, possessed of an "amiable disposition which precluded him from reaching true greatness".

Tony Murray is a retired civil engineer who has developed an interest in local engineering history. He spent most of his career with the Divisional Council of the Cape and its successors, and ended in charge of the Engineering Department of the Cape Metropolitan Council. He has written extensively on various aspects of his profession, and became the first chairman of the History and Heritage Panel of the South African Institution of Civil Engineering. Among other achievements he was responsible for persuading the American Society of Civil Engineers to award International Engineering Heritage Landmark status to the Woodhead dam on Table Mountain and the Lighthouse at Cape Agulhas. After serving for 10 years on SAICE Executive Board, in 2010 he received the rare honour of being made an Honorary Fellow of the Institution. Tony has written manuals, prepared lectures and developed extensive PowerPoint presentations on ways in which the relationship between municipal councillors and engineers can be more effective, and he has presented the course around the country. He has been a popular lecturer at UCT Summer School and has presented five series of talks about engineers and their achievements. He was President of the Owl Club in 2011. His book "Ninham Shand – the Man, the Practice", the story of the well-known consulting engineer and the company he founded, was published in 2010. In 2015 “Megastructures and Masterminds”, stories of some South African civil engineers and their achievements was written for the general public and appeared on the shelves of good bookstores. “Past Masters” a collection of his articles about 19th century South African Engineers is also available from the SAICE Bookshop.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.