Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The South African Constitution of 1996 introduced new forms of local government and radically changed the map of governance structures throughout the country. As has been the case since 1910, the central and provincial governments play a controlling role. However, at a local level – towns, cities and even townships and suburbs – remain arenas in which citizens are empowered to make their voices heard directly, as happens almost daily with street protests about inadequate service delivery. Local autonomy and responsibility have been crucial to popular expression, and, in this regard, it is salutary to recall the emergence of Randburg and Sandton as independent towns in 1959 and 1969 respectively.

Peri-Urban Settlements in the Johannesburg Region

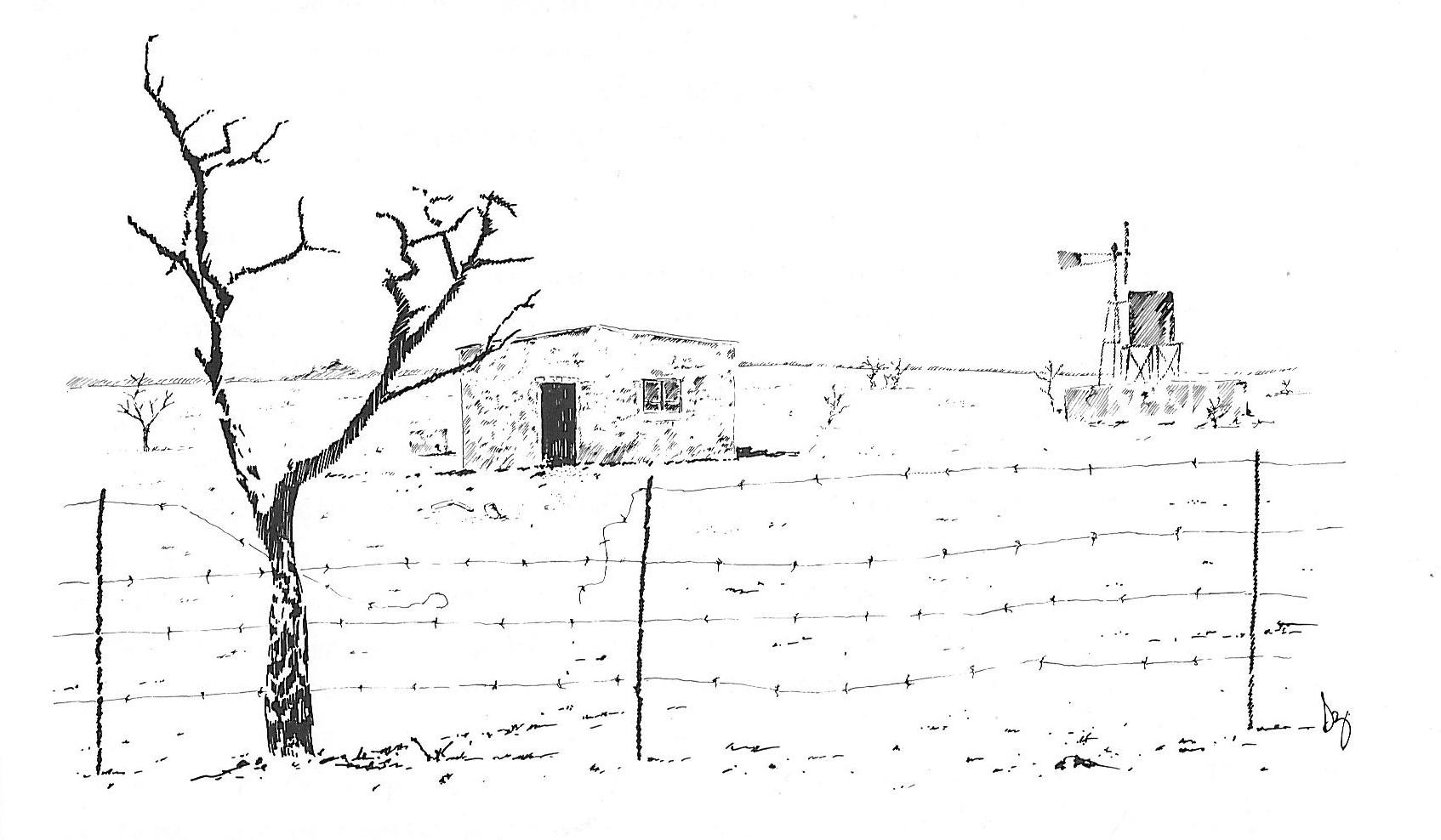

The area to the north of Johannesburg had been settled mainly during the 1920s and 1930s, when, as a consequence of drought, economic depression, and industrialisation, people fled the impoverished countryside hoping for employment and a better life in urban areas – many referred to it as the ‘Second Great Trek’. As remains the situation in our era, many newcomers settled on the periphery of towns, often living under insanitary conditions without services such as roads, electricity, health services, water, and sanitation.

In the 1930s Johannesburg was the city most impacted by the enormous increase in population and in 1936 appointed a commission under Richard Feetham (1874-1965), once a member of Lord Milner’s ‘Kindergarten’ after the South African War with responsibility for Johannesburg, by the 1930s a prominent judge and chairman of numerous high-profile commissions, and later Principal and then Chancellor of Wits University. Feetham was tasked with investigating whether Johannesburg should extend its boundaries to include these informal settlements. In the event, the commission decided that to do so would be unwise, because the city would overextend itself financially. Feetham concluded that in the areas north of Johannesburg, an independent and separate town should be established to levy rates and provide services. The provincial authorities however, decided otherwise and matters were left as they were.

Richard Feetham (Sketch by Duncan Butchart)

But by 1938 deleterious conditions in this ‘rural-urban fringe’ were so serious a problem that the central government intervened and appointed a national committee, under Sir Edward Thornton (1878-1946), to report on all irregular settlements on the periphery of South Africa’s towns. Thornton, who had joined the civil service in the Cape initially in 1903, had recently retired as Secretary of Public Health; he had also held the Chair of Public Health at Wits University and was extremely experienced and well respected. After many hundreds of site visits and interviews, Thornton’s committee found that in the provinces of Transvaal and Natal in particular, where there was no organisation for administering areas which did not form part of a local authority, viz. a town, village, or health committee, conditions in peri-urban settlements were the most insanitary. The majority of people living in them was ill-educated and poor, and therefore it was the Thornton committee's opinion that they did not have the ability to govern themselves and that they would not be able to form viable communities with leadership and financial strength.

Edward Thornton (Sketch by Duncan Butchart)

The Peri-Urban Areas Health Board

Resulting from Thornton’s report, the Transvaal province was directed to establish control, and this it accomplished in 1944 by forming – reluctantly – the Peri-Urban Areas Health Board (PUAHB) with headquarters in Pretoria and Thornton its chairman. The Board, whose members were analogous to town or city councillors, was given very wide powers: it could employ staff, levy rates, provide roads, town planning, health services, and electricity, water, and sewage schemes. The problem, however, was that it was an imposed structure that was undemocratic. No part of the PUAHB was elected by those affected, Thornton arguing that the residents of these places were not competent to govern themselves, at least initially, and that professional direction and policy should come from the Board.

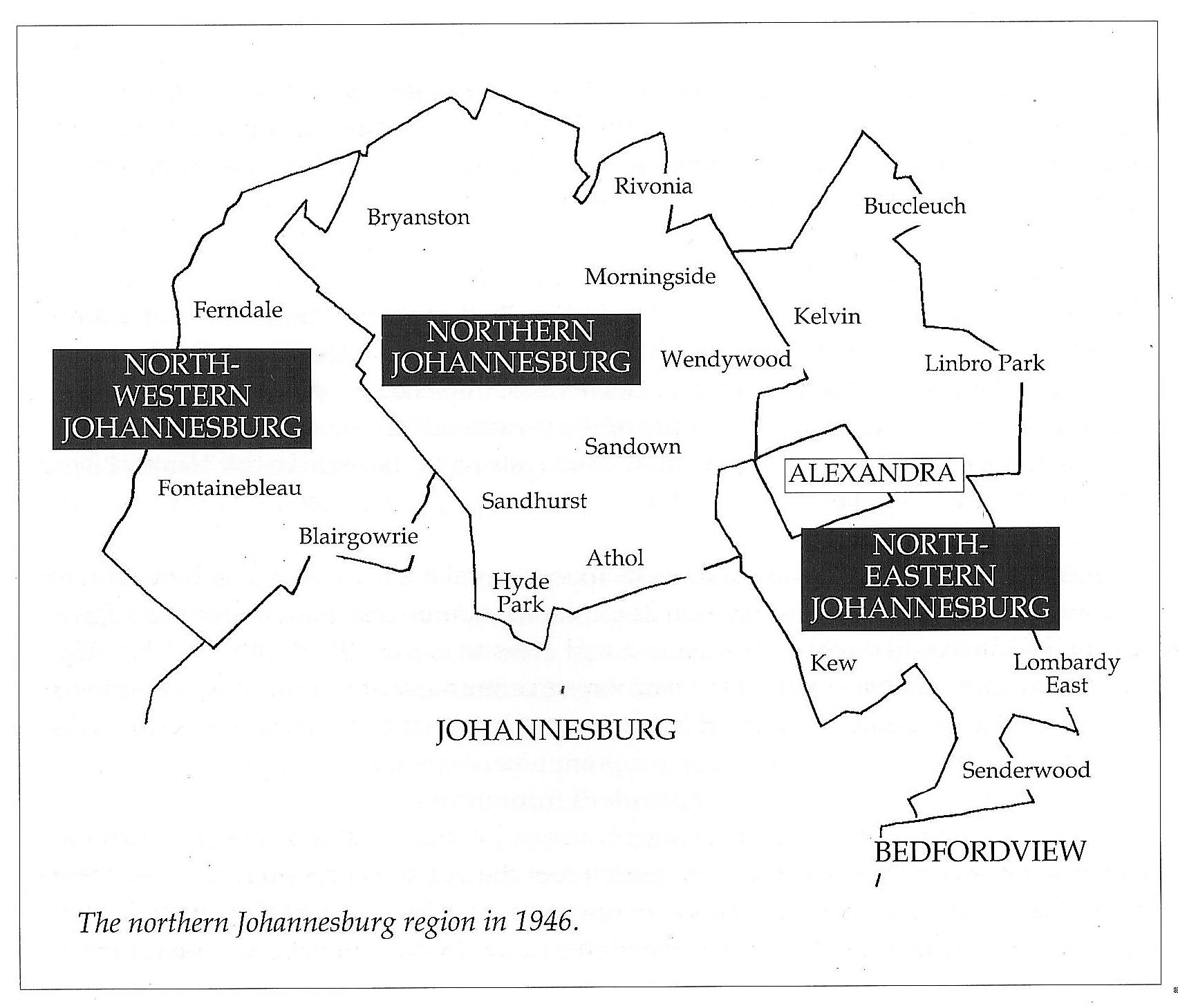

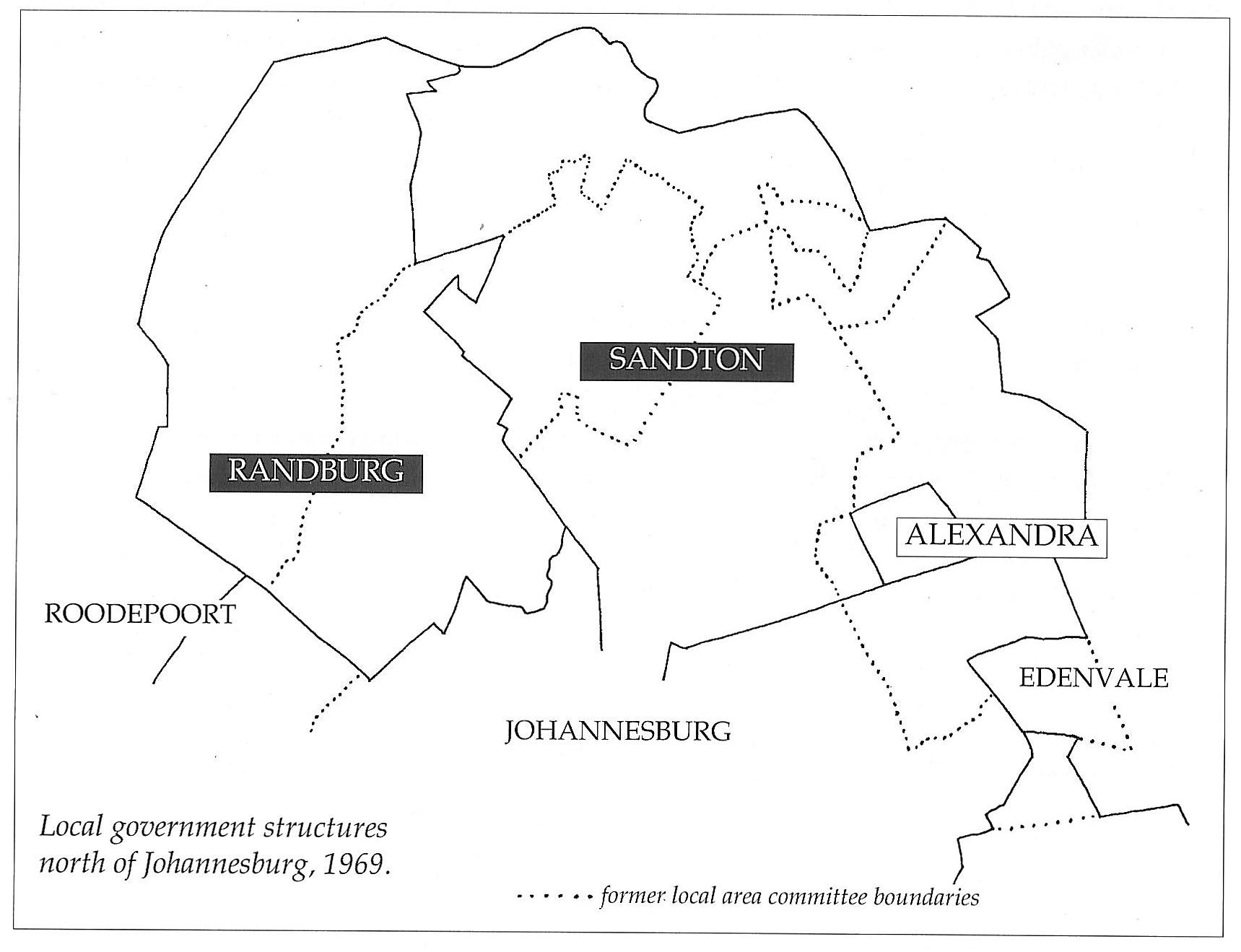

The Board governed two categories of peri-urban areas in the Transvaal. Of a total of some 23 000 km2 most was in the ’General Area’, predominantly rural in character, and in which no rates were levied or services provided apart from regular health inspections. More densely settled areas (some 1818 km2) were divided into Local Area Committees (LAC) and in these places residents were able to nominate committee members to work with the Board. These members, however, could not take any decisions but only make recommendations to the Board whose officials attended LAC meetings. Rates were levied in these areas and services were promised. In 1946 three LACs were established on the periphery of northern Johannesburg, the Northern, North-Eastern, and North-Western. Alexandra Township, then administered by a Health Committee, was excluded. (It was unilaterally transformed into a LAC under the PUAHB in 1958 with growing Group Areas legislation.)

Map of the region in 1946 (Sandton: The Making of a Town)

Alexandra Health Committee (The Heritage Portal)

From the outset, however, the PUAHB was contentious because it was undemocratic, as were LACs whose members were nominated by residents’ associations without election. For a time in 1946-1947 it was declared ultra vires for this reason, and the South African Constitution was (controversially) amended to include it (Act 41 of 1947). The start of the experiment did not run smoothly, with criticism levelled at the extremely wide powers of the Board, which, despite its name, embraced very much more than health. A further worry was when, if ever, the reign of the PUAHB would end, and if so, how would that happen? Was the PUAHB to become a permanent mega-structure or would new towns be created? None of this was made clear.

Before the Board was created, two health committees had operated in the North-Western Johannesburg Local Area, in Ferndale and in Fontainebleau, but the residents voluntarily joined the Board and dis-established them. The Northern Johannesburg and North-Eastern Johannesburg Local Areas experienced local government for the first time.

No indication was provided as to whether the areas were to be governed by the PUAHB in perpetuity, whether residents were ever to elect their representatives and become towns and villages in the future, or whether the traditional form of local government in the Transvaal was to be altered permanently by the creation of this Board. It might well have been more appropriate to have had a town council in the area to the north of Johannesburg from the start (as Feetham had recommended), rather than an imposed government by the PUAHB. Conditions there were not unsanitary or unhealthy, and such pockets of poor-white and mixed-race slums as existed could have been handled in the same way as did most other conventional local authorities when faced with slum problems. Much of the region was populated largely by middle-class whites, the majority of whom had come, not from the countryside, but from urban Johannesburg in search of a more rural environment and lifestyle. The financial strength of the northern LACS emerged when the Board levied rates which were virtually the same as those of municipalities and which were sufficient to contract services, such as roads, water, sewerage, etc.

Although all LACs contributed to a pool for administrative expenses, it was the policy of the Board to spend rates levied in a particular area on that area alone, and so the more the residents were prepared to pay, the better the services with which they were provided. There were also other reasons why the northern Johannesburg region fought to secede from the control of the Board from the outset. Associated with this was dissatisfaction with control exercised by a remote body in Pretoria, for it was often stated that secession would bring with it the benefit of decisions taken on the spot. Perhaps their belonging to a large, impersonal organisation also played a part, as did the fact that for many residents of the Northern Johannesburg LAC, the Board was dominated by supporters of the National Party while the area was a United Party stronghold.

Initiative towards autonomy

Agitation in the form of letters to the Administrator, petitions and protest meetings against the new administration began soon after the inauguration of the Board. This area was different from the majority of others governed by the Board in that there was leadership within the community, and it had financial strength. The undeniable benefits of association with a large co-operative society were outweighed in the minds of the community by the lack of effective representation. However, it should be borne in mind that any kind of control might have been unwelcome to peri-urban residents, for many had settled in these areas specifically to avoid controls.

Movements for autonomy in the Northern Johannesburg and North-Eastern Johannesburg local areas were disorganised and sporadic during the years 1945 to 1956. Agitation came from various quarters; from individuals, from residents' associations in different suburbs, and from the LACs themselves. The goal of some dissenters was complete and immediate autonomy while others would have been content with elected representation within the overall structure of the Board. Matters were further complicated by the existence of rival residents’ organisations, which alternated between vying with one another for the nomination of LAC members on the one hand, and disregarding the existence of that body on the other. It would seem that for the most part, however, these associations probably reflected the real views of residents, but because they were voluntary associations with no statutory powers, some of them represented vested or sectional interests. Without elections, the Board was obliged to deal with all of them in good faith. As provision had been made in an amending ordinance (No. 24 of 1948) for the election of LAC members (although the machinery by which these elections could be held had not been created), all these attempts at independence were pre-empted by the vague promise of eventual elected representation.

The Establishment of Randburg

Although there were similarities in the paths taken by Randburg and Sandton towards ultimate autonomy, there were also numerous differences. The initiative for the establishment of Randburg came neither from the Board, nor from the LAC, not even from a residents’ association, but from a self-appointed committee claiming to represent the views of residents and supporting its claim with a substantial petition. A dynamic leader, Robert van Tonder, emerged in this area, and in 1956 he founded the Dorpsraadaksiekomitee, the aim of which was to establish an independent town in the North-Western Johannesburg local area. Van Tonder was District Secretary of the National Party and it is clear that he expected political assistance in the formation of the new town, which would have an Afrikaans character as opposed to the English character of Johannesburg at that time which he regarded as communist leaning. The petition organised by this committee was presented to the Administrator on 4 June 1956 and, without consulting the PUAHB, he appointed a commission to inquire into the matter. The chairman of this commission was Theo Lorentz, a former PUAHB Board member (an appointee of the United Party who had been replaced by a Nationalist) and a well-known opponent of it. The Board, being of the opinion that the North-Western Johannesburg Local Area was not sufficiently developed for autonomy, was antagonistic towards this commission and officials of the Board had to be subpoenaed to appear before it. All the evidence presented to this commission, other than that from that by the Board, favoured independence. It is probably not coincidental that the momentum towards a referendum on whether South Africa was to become a republic was growing at this time. (It was held on 5 October 1960.) There was no doubt that Randburg would have a National Party dominated town council.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the Lorentz Commission found in favour of autonomy and, despite a lengthy counter-memorandum from the Board protesting vehemently against it, the Administrator agreed to the establishment of a town in this area. After various delays Randburg came into being on 1 July 1959.

Robert van Tonder (Sketch by Duncan Butchart)

Theo Lorentz (Sketch by Duncan Butchart)

Local Elections

It was during the course of the Lorentz Commission's deliberations that the regulations governing the elections of LACs were promulgated by the Administrator. Elections were held in the North-Western Johannesburg LAC before it became Randburg, so that the elected LAC members could serve as the first town council. These long-awaited elections elicited quite different reactions. In the North-Western Johannesburg LAC, where autonomy was imminent, enthusiasm ran high. But the people of Northern and North-Eastern Johannesburg remained distinctly apathetic in the absence of any promise of real change to the existing order and most LAC members were elected unopposed.

However, the success of the residents in the North-Western Johannesburg LAC in obtaining their independence provided an impetus for the other areas to the north of Johannesburg to exert further pressure for autonomy. Letters and petitions from residents' associations continued with renewed vigour.

The PUAHB vs Transvaal Province

In the 1950s the relationship between the Board and the Province began to deteriorate and, as has been seen in the case of Randburg, it was hostile. When it was first established, the Board foresaw a lack of co-operation from the people it governed, but it did not expect the same treatment from its creators, the province. The early subsidy from the province was small, even by the standards of the 1940s, and the Board levied rates in order to build up its organisation and to provide services. This was, of course, part of its function, but rates were levied retrospectively in the region north of Johannesburg and residents objected strongly to paying for services and administration which they had not yet received. Instead of inviting criticism and engendering hostility by taking this course of action, the Board might have approached the province for a larger subsidy; but from subsequent events it seems that the Board was reluctant to ask favours of the province, for fear that ‘he who pays the piper calls the tune’. Intent on retaining its power, by 1952 the dissension between some members of the Board and the Province was tacitly admitted, even mentioned in the press and in the Provincial Council. As a result, another commission of inquiry was instituted, under Charles E. Barry (1877-1956), a former Judge President of the Transvaal.

The issue for Barry’s commission was not to consider the independence issue which arose later with Lorentz and Randburg, but to clarify what position the Board should occupy in the overall provincial structure. After hearing extensive evidence, this commission recommended that the Board should alter its name and its character and become a developmental body, whose aim would be to establish viable conventional local self-governing units in the shortest possible time. The Board’s counter argument, articulated in its own separate internal commission, was that it had not rectified all the insanitary areas under its control and provided appropriate services and it was reluctant to leave these places to their fate as financially insecure and incompetently administered towns and villages which is what the Board considered that Randburg would be. Democratic government was to be sacrificed to efficient administration.

Moreover, and importantly in terms of the structure of power, the Board was also concerned that if it became public knowledge that it was a diminishing body, competent staff then at the disposal of all local areas would not be attracted to its service because long-term professional employment could not be guaranteed. It assured the provincial authorities that when the time was ripe – and this would be at the Board's discretion – local self-governing towns could be created from local areas. But the Province rejected the Board’s opinions and autonomy was to go ahead wherever, and as soon as, possible.

The Foundation of Sandton

In fact, the Randburg decision had indicated to the Board that its arguments around efficiency versus democracy would be rejected. By the early 1960s its mandate was to actively assist well-developed and suitable areas to attain their independence. By 1964 it had begun to help the Sandown LAC (the Northern Johannesburg LAC had been split into two: Sandown and Bryanston) in its endeavours to secede. An inquiry had also been made into the viability of the North-Eastern Johannesburg LAC. This was done at the request of the LAC which was under some pressure from residents’ associations in the region, but the report prepared by the Board indicated that it would not form a suitable local authority area and that it should remain under the Board’s administration. After many meetings to try to resolve the matter, finally, in August 1964, a suggestion was made by a member of the North-Eastern Johannesburg LAC that it and the two divisions of the former Northern Johannesburg LAC – Bryanston and Sandown LACs – should combine to form one sustainable large town rather than three small ones. After making a full report, the Board agreed with the suggestion that together they would form a suitable and viable unit for a municipality and began to take steps to make that a reality. But the Administrator did not enthusiastically and immediately endorse this proposal and, in November 1965, he set up yet another commission of inquiry, this time with J.S. van der Spuy as Chairman, to investigate the position. At this juncture, other Witwatersrand municipalities – particularly Johannesburg – saw the opportunity to increase their own revenue streams, areas of control, and development strategies, and formally objected to the formation of the new town. They applied for the incorporation of parts of the three LACs into their respective municipal areas.

The Commission was directed to investigate all these applications to cannibalise the region and, as a result, the whole matter of governing and administering the metropolitan area of the Witwatersrand was debated, rather as Thornton’s committee had done in 1939. It was clear from witnesses during investigations of the Van der Spuy Commission – usually referred to as the ‘Greater Johannesburg Commission’ – that Johannesburg, the core and chief city on the Witwatersrand, was experiencing difficulties in planning its future growth, since these plans could be obstructed by other municipalities on its periphery which did not share its planning needs or have the finance involved to co-operate. In effect, Johannesburg wanted to assume the role of a regional governing body rather like the Board. It argued, as had the Board in similar circumstances, that regional government would be more efficient and cooperative schemes easier and cheaper to finance and provide. However, the Province decided not to depart from established convention or change the traditional form of local government in the Transvaal and accepted Van der Spuy’s report of 1967 that the three LACs to the north of Johannesburg should become another Reef town.

On 1 July 1969, the LACs to the north of Johannesburg, with suitable boundary adjustments, and with the loss of small portions to Johannesburg, Bedfordview, and Edenvale, became the municipality of Sandton. Its foundation formally ended almost three decades of government by the Board. It was to exist as a separate town for about the same length of time.

Adjusted municipal boundaries 1969 (Sandton: The Making of a Town)

Conclusion

Since the period covered in this brief survey, under the 1996 fully democratic Constitution of the Republic, local government has been transformed once again, this time going against the grain of history and favouring larger administrative structures rather than small, separated units. According to law, there are three categories of municipality, one of which is ‘metropolitan’. In Gauteng, these are Johannesburg, Ekhuruleni, and Tshwane. The Johannesburg Metro has engulfed both Randburg and Sandton, as well as many other once autonomous towns and cities. Metro councils are single employers, have single budgets, common property ratings and service tariffs, but they may decentralise some powers and functions. Replacing the other types of areas that were administered by the PUAHB are district and local municipalities which are also new structures. Unlike parliamentary party lists for parliament seats, local government ward councillors are elected directly by residents on a mixed-member basis. Consequently, residents are able to hold their local councillors to account and target them with service delivery failures as they so frequently do.

The Johannesburg Council Chambers (The Heritage Portal)

Although local government is the lowest tier of government, and is often marginalised for that reason, it is the most important arena of the state that determines the everyday lives of citizens. As explained by Sir John Maud in 1938 in words that remain valid today, city government in the Johannesburg region has always been experimental, it is about reconciling freedom with efficiency, its function is to be of positive service to the community ensuring health, economic opportunity, and happiness. The history of how, and to what extent, these goals have been achieved is thus an important area of study.

Main image: Typical peri-urban plot c.1940 - Duncan Butchart

About the author: Jane Carruthers is Professor Emeritus at the University of South Africa, elected Fellow of the Royal Society of South Africa and Member of the Academy of Science of South Africa. She has been awarded many international visiting research Fellowships, including at Cambridge University, the Australian National University and others. She is a former President of the International Consortium of Environmental History Organizations, the Southern African Historical Society, Chair of the Academic Board of the Rachel Carson Centre Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich, Editor-in-Chief of the South African Journal of Science, and recipient of the Distinguished Scholar Award from the American Society for Environmental History. She pioneered the discipline of environmental history in South Africa and her book, The Kruger National Park: A Social and Political History (1995) has become a standard reference worldwide. Her research interests are broad, and include environment history, national parks, the history of science, land reform, colonial art, ad comparative Australian-South African history. She is the author of numerous books, as well as many book chapters and articles in scholarly journals.

References:

- Beavon, Keith, Johannesburg: The making and shaping of the city. Pretoria: Unisa Press, 2004.

- Bonner, Philip and Nieftagodien, Noor, Alexandra: A history. Johannesburg: Wits UniversityPress, 2001.

- Carruthers, E.J., ‘The growth of local self-government in the peri-urban areas north of Johannesburg, 1939-1969’. Unpublished MA dissertation, UNISA, 1980.

- Carruthers, Jane, Sandton: The making of a town. Sandton: Celt Books, 1995.

- Maud, John P.R., City government: The Johannesburg experiment. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1938.

- Republic of South Africa, Local Government: Municipal Structures Act, 1998 (Act 117 of 1998).

- Van Tonder, Robert, Hoe Randburg onstaan het. Randburg: Postma Publikasies, 1984.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.