Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

“I have had, in the last four years, the advantage, if it be an advantage, of many strange and varied experiences. But nothing was so thrilling as this: to wait and struggle among these clanging, rending iron boxes, with the repeated explosions of the shells and the artillery, the grunting and puffing of the engine – poor, tortured thing, harassed by at least a dozen shells, any one of which, by penetrating the boiler, might have made an end to it all”. W.L.S. Churchill.

Young Churchill (Imperial War Museum)

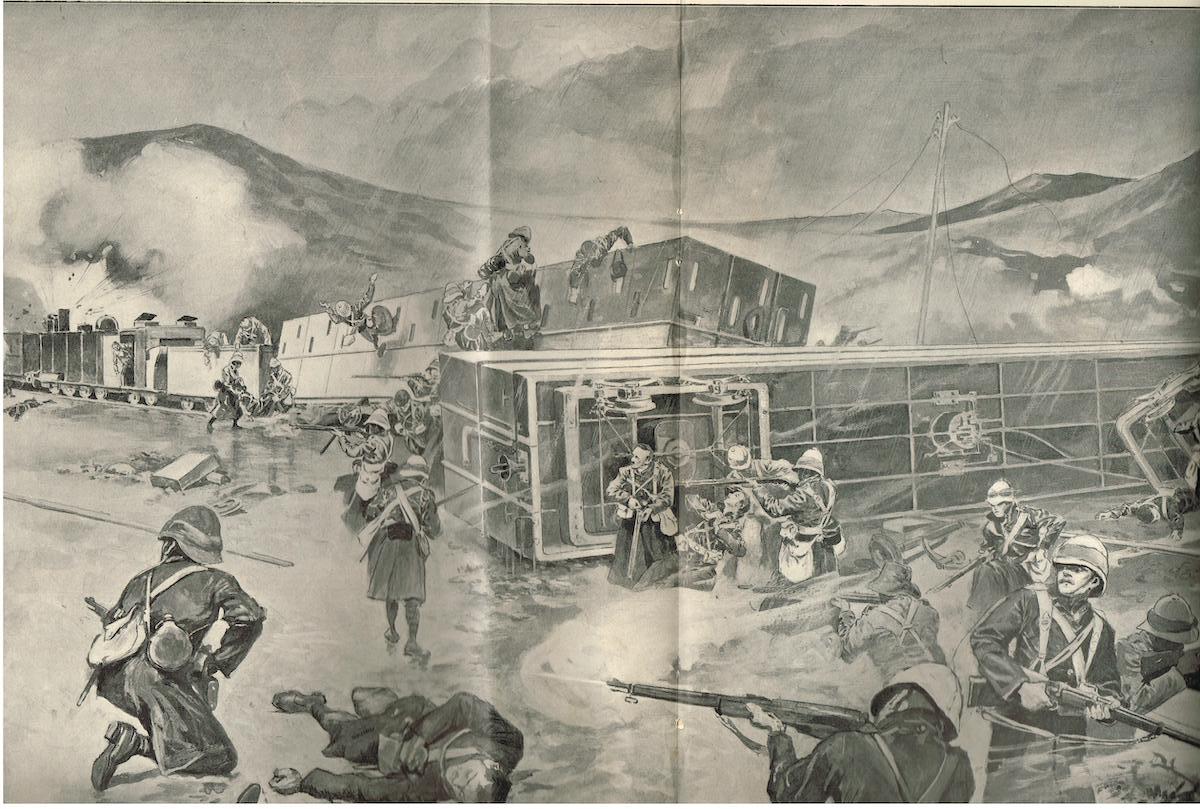

With Ladysmith besieged by Boer forces, by early November 1899 the main body of British troops had retired south of the Tugela River, basing itself at Estcourt. In a sort of “phoney war”, extensive scouting was carried out around Estcourt south to Willow Grange, west towards the Drakensberg Mountains and north towards Colenso, including the use of an “armoured train” which made periodic forays up the line to Frere, Chieveley and Colenso. However, the use of an armoured train as a reconnaissance vehicle was somewhat of an oxymoron. It could be seen and heard for miles, and any Boers in the vicinity merely had to take cover and wait for it to pass. Indeed, the armoured train that ran regularly up the line from Estcourt to Colenso was known as “Wilson’s Death Trap”, with good cause.

The Times History of the War Volume II (pages 304 – 305) concludes:

That the train was certain to be caught in a trap, sooner or later, was the outspoken conviction of every officer in Estcourt, but no precautions were taken to accompany it by a few mounted men to scout on both sides of the railway.

Between Estcourt and Colenso the line ran like a switchback, up and down a number of narrow valleys, with hardly a point from which an unbroken view of 800 yards on either side could be obtained. On the other hand, even when it was hidden in cuttings the puffing of its approach could be heard for miles. The particular train in question was of the most primitive character, consisting simply of open trucks boxed in with thick loop-holed walls of thick boiler plate to a height of seven feet from the floor of the trucks. It would be hard to devise a better target than a soldier laboriously climbing in and out of that death-trap.

According to The Durban Light Infantry 1854 – 1934 by Lt. Col. A.C. Martin (page 61):

It was decided to send out the Armoured Train on another sortie on the 15th (November 1899). Thus were sent a company of Dublin Fusiliers, Lt. Frankland and 72 men; 45 men of “C” Company of the Durban Light Infantry under Captain J.S. Wylie and Lieut. W. Alexander, and a detachment of 5 men of H.M.S. Tartar with a 7-pdr. under a petty officer. Capt. A. Haldane, D.S.O., of the Gordon Highlanders, recently recovered from wounds at Elandslaagte, was placed in command. Accompanying the train were some platelayers, telegraphists, and linesmen, and Mr. Winston Churchill, War Correspondent to the Morning Post.

At the head of the train was an open flat truck carrying an antiquated 7-pdr. manned by men of H.M.S. Tartar. Then came an armoured truck in which were three sections of the Dublin Fusiliers, Captain Haldane and Winston Churchill. This was followed by the engine and tender, two armoured trucks, and an open bogie. In the truck behind the engine and tender were the fourth section of Fusiliers, Capt. Wylie and half the men of the Durban Light Infantry. The following truck contained Lieut. Alexander, the remainder of the Durban Light Infantry, the telegraphists, platelayers and the like. The bogie carried the stores thought necessary, and the guard.

The driver of the train was Charles Wagner, with Stoker Alexander James Stewart, linesmen Charles Godfrey DCM., A. Bramley, William Yallup (formerly Railway Section, Dundee Town Guard and present at Talana) and James Welsh. The telegraphists referred to were Robert Taylor McArthur and A.R. Foster. The latter had been specially assigned to Winston Churchill for the transmission of press reports.

Randolph S. Churchill, in his book Winston S. Churchill – Youth 1874 to 1900, quotes Captain Aylmer Haldane’s report to the Chief of Staff, Natal Field Force:

Left Estcourt at 5:10 a.m. and on arrival at Frere Station at 6:20 a.m. I reported that no enemy had been seen. Here I met a party of eight men of the Natal Mounted Police, from whom I learnt that their patrols were in advance reconnoitring towards Chieveley, wither I proceeded after a halt of 15 minutes. On reaching there at 7:10 a.m., I received the following message by telephone from Estcourt “Remain at Frere in observation, watching your safe retreat. Remember that Chieveley station was last night occupied by the enemy. Nothing occurred here yet. Do not place reliance on any reports from local residents as they may be untrustworthy”, and in acknowledging it stated that a party of about 50 Boers and three wagons was visible moving south on the west side of the railway.

I at once retired towards Frere, and on rounding the spur of a hill which commanded the line the enemy opened on us at 600 yards with artillery, one shell striking the leading truck”.

This small hill referred to by Haldane lies west of the railway line less than two miles from Frere. According to Martin, the occupants of the train saw a cluster of Boers gathered on the top, and the next thing they heard was the crash of shrapnel shells bursting overhead. The engine driver put on steam, but the train was unable to make the turn at the bottom of the hill. With an almighty crash, the bogie “was thrown into the air and landed off the line, up-side down. The armoured truck next to it was derailed and thrown on its side, spilling out its occupants and pinning some of them under, and crushing one”.

Attacking the train

There have been several theories as to what caused the derailment. According to Haldane, “the enemy, lying in ambush, had allowed the train to pass towards Chieveley, and had then placed a stone on the line, which the guard, probably owing to the shell fire, had neither seen nor reported”.

Winston Churchill writes of a huge stone placed on the line, which is backed-up by official Boer accounts. Burleigh states that the Boers had removed the fishplates and propped the line up with stones. The Times History states that stones were placed between the guide rail and outer rail. R.A. Curry, driver of a light engine that had piloted the train as far as Frere, stated that bolts were removed and had to be replaced by the platelayers. Whatever the cause, it is almost certain that the speed of the train also contributed to the derailment.

Martin records that:

The next armoured truck in which was Capt. Wylie, was partly on and partly off the line, leaning over on one side and obstructing the line so as to trap the rest of the train. Many were injured. All were shocked, having been thrown violently to the ground or to the floor of their truck.

Winston Churchill’s belated despatch for the Morning Post describes the incident:

The Boers held their fire – suddenly three wheeled things appeared on the crest, and within a second a bright flash of light … then two much larger flashes … the iron sides of the truck tanged with the patter of bullets. There was a crash from the front of the train … the Boers had opened fire on us at 600 yards with two large field guns … and a Maxim. I got down from my box into the cover of the armoured sides of the car … the driver put on full speed, as the enemy had intended.

The train leapt forward, ran the gauntlet of the guns, which now filled the air with explosions, swung round the curve of the hill, ran down a steep gradient, and dashed into a huge stone.

To those … in the rear truck there was a tremendous shock, a tremendous crash, and a sudden full stop. The truck containing the tools and materials of the breakdown gang and guard was flung into the air and fell bottom-upwards on the embankment. The next, an armoured car crowded with Durban Light Infantry, was carried on twenty yards and thrown over onto its side, scattering its occupants in a shower on the ground. The third wedged itself across the tracks, half on and half off the rails.

Haldane states that:

Mr. Winston Churchill, special correspondent of the Morning Post, who was with me in the truck next to the gun-truck, offered his services, and knowing how thoroughly I could rely on him, I gladly accepted them, and undertook to keep down the enemy’s fire while he endeavoured to clear the line. Our gun came into action at 900 yards, but after four rounds was struck by a shell and knocked over. I recalled the gun detachment into the armoured truck, whence a continuous fire was kept up on the enemy’s guns, considerably disconcerting their aim, as I was afterwards informed, killing two and wounding four men.

Churchill encouraged Wagner, the engine driver, to climb back into his cab, and reported to Capt. Haldane that he believed there was a chance of clearing the line if the enemy were kept engaged and some volunteers assisted him. Unfortunately only 9 men answered his call, the remainder preferring to take cover behind the trucks and embankment.

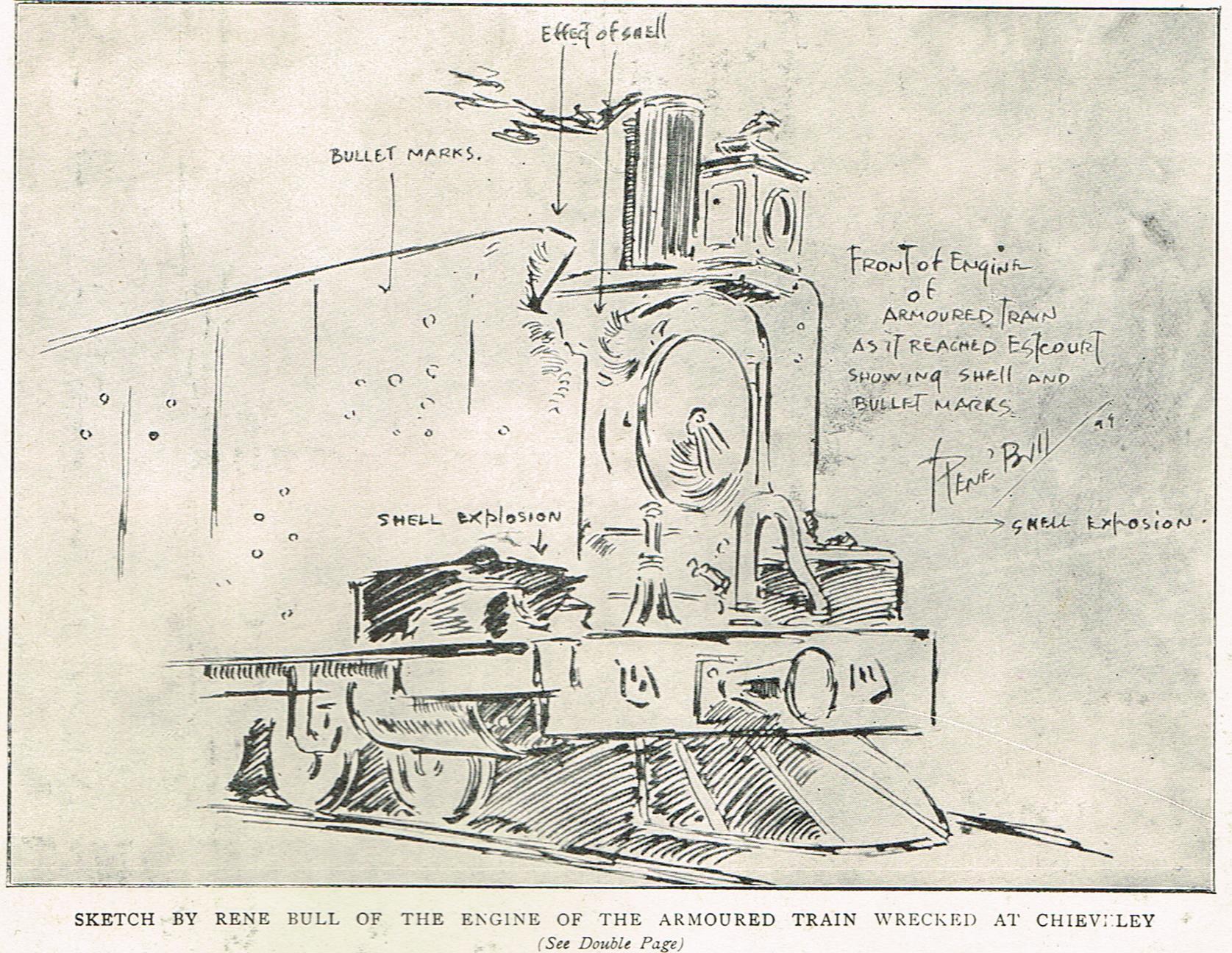

Sketch of the engine of the armoured train

For the next seventy minutes, under a storm of small arms fire, the partially derailed truck next to the tender had to be bumped off the line by the engine in order to clear it. Churchill managed to persuade Driver Wagner to stay at his post by telling him that, although he had received a head wound from a splinter, it was impossible to be hit twice on the same day!

They finally managed to partially dislodge the truck, to the point where the engine and tender just managed to squeeze past. As they did so, however, the truck slipped back, making it impossible for the engine to hitch up the other trucks, which were now stranded on the other side of the obstacle.

Capt. Haldane gave the order for:

as many wounded as possible to be loaded on the engine and tender and for it to make its way slowly so as to provide some cover for the men who were to fight their way back to some houses near Frere where it was proposed to make a stand.

So the engine started back accompanied by the men on foot. There was an immediate increase in the volume of Boer fire and soon about a quarter of the force was killed or wounded. The engine was being hit, its tender was set alight in part, and so the driver increased speed, and soon the infantry were left behind. Winston Churchill, who was on the engine up to this moment, decided to go back to the men fighting their rearguard action, but not before instructing the driver to make for the far side of the bridge over the Blauuwkranz River near Frere.

By that time it was all over with the infantry. They had become scattered and one man, wounded, put up a white handkerchief.

According to Winston Churchill:

As many wounded as possible were piled onto the engine, standing in the cab, lying on the tender or clinging to the cowcatcher … (The Maxim) discharging with an ugly thud, thud, thud exploded with startling bangs on all sides. One struck the footplate of the engine scarcely a yard from my head … another hit the coals in the tender, hurling a black shower in the air. A third struck the arm of a Private in the Dublin Fusiliers. The whole arm was smashed to a horrid pulp – bones, muscle, blood and uniform all mixed together.

Robert Taylor McArthur, who had recently lost his employment as a Clerk at the Glencoe Post Office after the battle of Talana and subsequent evacuation of Dundee, had signed up as a civilian employee on the Governor’s staff. He later wrote an account of his experiences during the incident, which was published in Bennett Burleigh’s The Natal Campaign (pages 82 – 83).

We left Estcourt at 5:30 a.m., and ran on to Ennersdale, and reported by wire, “All clear”. Shortly before reaching Frere we met and spoke to some of the Natal Police, who had been bivouacking upon the kopjies. They told us that the Boers had all gone back the previous night.

Then we went to Frere, where we wired the General, “All well”, and without waiting for a reply ran on to Chieveley. Shortly before entering the station we saw fifty Boers going west at a canter with some wagons, as we thought. We waited a few minutes at Chieveley, and then started back.

About three miles out, or two miles north of Frere, we noticed several hundred Boers about 800 yards off, on the west side. Then we saw more on the east of the line. They began firing at us, first with rifles and then with Maxim-Nordenfeldt cannon. One of their shots made a big dent in the rear armoured truck, but did not enter. Their guns were behind the kopje; at least, two repeating cannon, which shot a steady flame, and a heavier piece that threw shrapnel at us.

But a few yards on our rear, then, the front truck ran off the line, shaking and jolting terribly, and ours, the next or armoured one, followed suit, and soon all three left the rails. The next thing I knew we were all upset, and, strangely, only one man was killed. We all scrambled out.

Sitting down, the soldiers began firing volleys at the Boers, who responded by peppering us with more shot and shell. In about five minutes Mr. Churchill came from what had been the front of the train, took charge, and asked for volunteers to shift the trucks. About fifteen men helped to do so, but the wagons were too heavy to move. Then the engine managed to smash through, breaking them up, and getting knocked about in doing so. All this was done under heavy fire.

We tried to couple up the trucks that had been in front, but could not, the line being blocked. Then, picking up all the wounded we could see, we started for Frere to get assistance. My instruments were smashed, and we found those at Frere had been carried off by the Police for safekeeping. From there we pushed ahead to Ennersdale, whence I wired to the General, giving him a few details. We had several men shot down whilst we were putting the wounded on the tender, although our troops did their best to cover the operation by firing volleys. Several of the shells struck the telegraph wires and poles, cutting and knocking down the line.

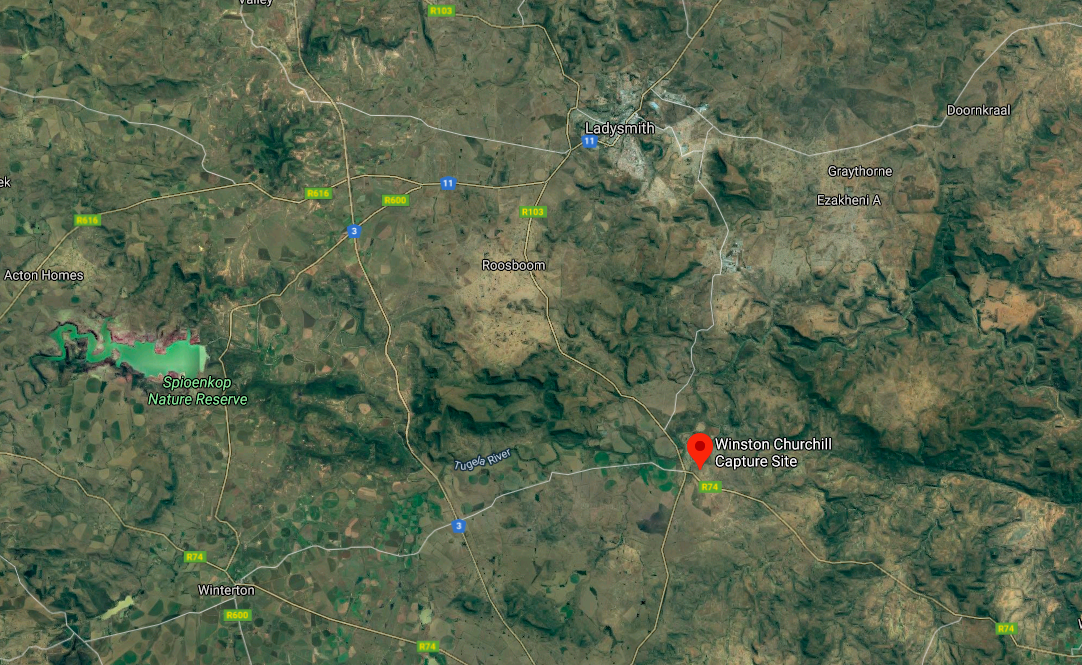

Churchill’s stated objective of rounding up stragglers was, however, untenable. On his way back to the train, two Boers caught Churchill in a railway cutting. He scrambled up the bank in an attempt to escape, only to find a mounted Boer waiting for him, some 40 yards away. According to Pakenham, this Boer is alleged to have been Veld Cornet Sarel Oosthuizen, known as the “Red Bull of Krugersdorp”. Churchill decided that there was no hope of escape, and surrendered.

Capture Site (Google Maps)

The Durban Light Infantry Volume 1 1854 – 1934 by A.C. Martin (page 67) also quotes Dr. Raymond Maxwell’s first hand recollections. He was then serving as a British Doctor with the Red Cross Ambulances attached to the Boer forces.

The rain came down in torrents all day, and our mules only made slow progress, but we caught up with our commando at Chieveley station. Heard rifle and artillery fire from here, and on getting on towards Frere station found the Boers just capturing an armoured train and some 56 prisoners. The train had come up from Estcourt to Chieveley, passing through Boers lying on both sides of the line without seeing them. While it was up at Chieveley, some Boers went and fixed in big stones just where the line crossed a culvert. Just as they were finished, back came the train at a great rate with the engine in the middle. On reaching the obstruction the wheels on one side left the line, but still it ran 250 yards without overturning, but then the front trucks upset trying to negotiate a curve, and one lay across the line obstructing further progress.

All the time the Boers were pouring in a dreadful fire from practically perfect cover, and the artillery kept putting shells clean through the trucks. At last the engine managed to butt the obstructing truck out of the way, and got off loaded up with what seemed about 40 men. The other soldiers who had been lying behind what cover they could get were compelled to surrender, several of them being wounded.

In one of the overturned trucks there were three dead soldiers, one being a D.L.I. man (Pte. F. Copeland) and further down the line were two more dead soldiers.

Sometime later a party of the Ermelo Commando, who had gone on ahead to break up the line, were completely surprised by a patrol, and received a volley without any warning, which killed two men.

The “patrol” referred to comprised two squadrons of the Composite Regiment, one from the Imperial Light Horse (“A” Squadron under Capt. Herbert Bottomley) and the other of the Natal Carbineers, under Major Duncan McKenzie. This encounter was of great assistance in enabling the engine, as well as a number of men, who made their way on foot to Estcourt, to get away.

According to G.F. Gibson in his Story of the Imperial Light Horse:

A Squadron ILH and an NC Squadron, numbering some 160 men, under Major Duncan McKenzie, were sent to attempt to rescue the armoured train. They extended, and with reckless gallantry charged headlong into the midst of some 2 000 Boers who were busily employed in completing the wreck of the armoured train.

In thus engaging the enemy, the ILH and Carbineers would probably all have been killed or captured, had not a tropical storm descended suddenly. Under cover of the downpour, the squadrons were able to extricate themselves from this dangerous position, and cover the withdrawal of the engine and tender, with its load of men hanging on precariously.

Trooper Fred A. Freshney’s account My Experiences in the South African War gives a more realistic estimation of Boer numbers:

The news spread that the armoured train had been upset near Frere, and that we (“A” Troop) were to go to their assistance. We went “full gallop” in the pouring rain, and very soon horses and men were covered in mud, but we were far to excited to even notice this.

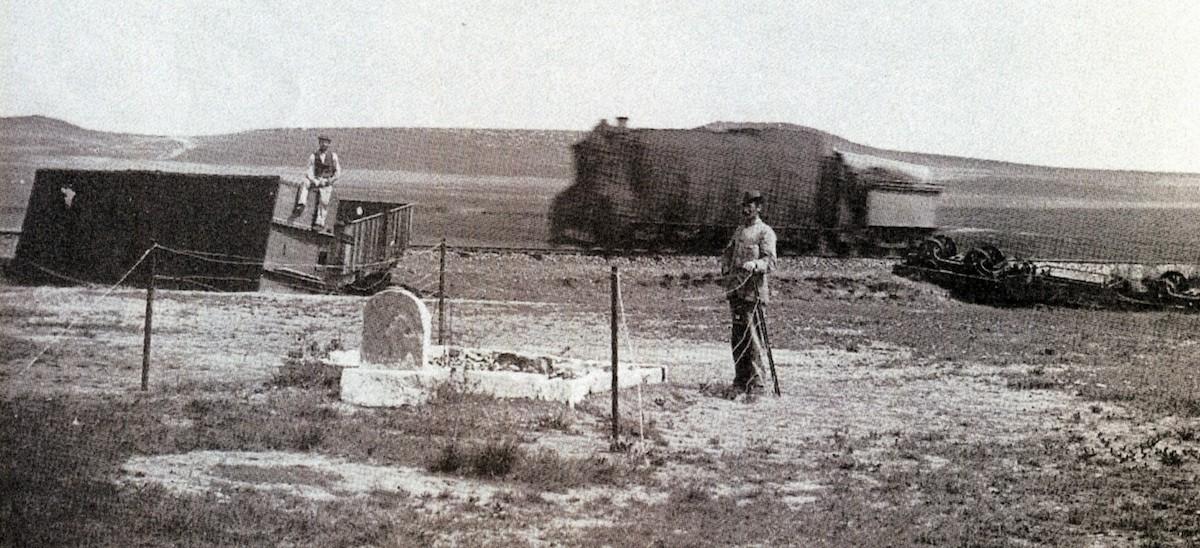

About 1½ miles out of Estcourt we met the engine of the ill-fated train coming slowly in with its load of dead and wounded – a sad spectacle. The poor wounded were lying on the coals, some on the cow-catcher, some on top of the boiler and one even clinging to the chimney. The engine itself had been badly battered by the shellfire, and was leaking in several places. We stopped a moment to get further information from them, and then were off again at full speed.

In a short time we reached Ennersdale Station (six miles out) … found that the Boers had looted the stationmaster’s house and the station buildings.

Once again we went by the side of the railway … we had gone about 4 miles north of Ennersdale, when suddenly “crack” went a rifle to our right, to be followed immediately by others from our men – we had taken a Boer Commando of about 300 strong by surprise. They were in a valley about 600 yards away, and just rounding a curve out of sight. We dismounted as quickly as possible, and began blazing away at their rear.

The Boers now took up position about 800 yards away and began to return our fire. Trooper Hillhouse (the smallest man in our Squadron) being shot through the knee. We had taken cover behind some Kaffir kraals … Major McKenzie … gradually withdrew, the Boers pressing us up to Ennersdale Station.

Dr. George Oliver Moorhead, who was serving with the Red Cross attached to the Middelburg Commando, then stationed at Chieveley, said that some 50 British surrendered. He saw them soon afterwards, “trudging towards us in the rain and mud, a little compact body of men on foot surrounded by mounted burghers. As they came near us we distinguished the sodden soiled khaki uniforms; a few officers marched stolidly in front, a man in mufti with an injured hand among them". This was, of course, Winston Churchill.

When the prisoners arrived at Elandslaagte, the railway official in charge of that section of the line, Mr. William Pratt, recalled ”It began to rain, and when the prisoners were told to seek shelter in the baggage van., Churchill was taken to one side and put in the ticket office. But the fun started when they were all told to board the train. One or two officers who had just joined the party objected to travelling with a newspaperman”.

This is extraordinary considering Churchill’s military background and connections. Perhaps the officers concerned were worried of the repercussions should Churchill succeed in escaping? In any event, Mr. Pratt bundled them all together onto the train bound for a POW camp in Pretoria.

Meanwhile the engine and tender had arrived back at Estcourt with the survivors at 10 a.m. It had taken three hits by shells, and the tender had 63 bullet strikes.

According to official records, there had been 5 killed, 2 who died of wounds and 47 wounded on the British side. 20 wounded and 70 unwounded got back to Estcourt. However, these figures do not tie-in with the Hayward Roll.

Captain Aylmer Haldane’s report to the Chief of Staff, Natal Field Force mentions those men who did well:

2nd. Lieutenant T.C. Frankland, 2nd. Bn. Royal Dublin Fusiliers, a gallant young officer who carried out my orders with coolness.

A.B. Seaman E. Read, H.M.S. Tartar, No. 6300 Lance Corporal W. Connell, Privates Phoenix and Cavanagh, 2nd. Bn. Royal Dublin Fusiliers who, notwithstanding that they were repeatedly knocked down by the concussion of the shells striking the armoured truck, continued steadily to fire until ordered to cease. Captain Wylie and the men of the Durban Light Infantry, who ably assisted in covering the working party engaged in clearing the line, and who were much exposed to the enemy’s fire.

The driver of the engine (Wagner) who, though wounded, remained at his post.

The telegraphist (R.T. McArthur) attached to the train, who showed a fine example of cheerfulness and indifference to danger.

Captain Wylie, who commanded “C” Company of the D.L.I. contingent on that day, was later asked what he thought of Winston Churchill’s conduct. Wylie replied “He was a very brave man but a damned fool”.

Postscript

Churchill was back in action a month later, having escaped (and made his name a household word in the process) from the New Model School in Pretoria and making his way to freedom via Delagoa Bay.

On his way back to the coast he called in at the railway workshops in Pietermaritzburg and asked to speak to Driver Wagner. However, Wagner was busy with some maintenance and declined to see his distinguished visitor as he was not in a fit state to do so. Churchill would not take “no” for an answer. “Dirty overalls are nothing compared to what he and I went through together. I have to shake his hand, oil and all! When, in 1910, I was Home Secretary, it was my duty to advise the King upon the awards of the Albert Medal. I therefore revived the old records, communicated with the Governor of Natal and the railway company, and ultimately both the driver and his fireman received the highest award for gallantry open to civilians."

Why, you might ask, have I bothered to research and write this article? Well, as someone once said, courage never goes out of fashion. And 2nd Class Railway Fireman Alexander James Stewart’s Albert Medal Second Class and his Queen’s South Africa medal came up on the May 2018 Dix Noonan and Webb catalogue. Hell, how I wished I had 20 000 Pounds to spare!

Roll of Honour

At the site of the action the graves of Privates 5031 J. Burney, 5861 E. McGuire and 5792 M. Balfe of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers can be found, just across the railway line on the opposite side to where the Churchill capture memorial now stands.

5263 Private C. Johnstone Royal Dublin Fusiliers died of his wounds at Estcourt on 22 November. 3993 Colour Sergeant P.J. Magee is recorded as having died on 15 November, although Steve Watt shows that he died on 15 December and is buried at Ambleside.

806 Private F. Copeland of the Durban Light Infantry is buried at Chieveley, 401 Private E. Espeland at Estcourt and 516 Corporal David Brown was crushed and subsequently died of his injuries on 23 December 1899. He is buried at Intombi Camp, Ladysmith.

The attached list (click here to view) is an attempted reconciliation between the Hayward Roll, “Volunteers All” and “The Durban Light Infantry”. However, there are a number of discrepancies and, in the absence of a Regimental Number, there is still some doubt as to correct spellings of surnames and, in that case, positively placing them at the scene.

About the author: Pat Rundgren was born in Kenya and grew up in what was then Bechuanaland and Rhodesia. He has nearly 10 years infantry experience as a former member of the Rhodesian Security Services. He is passionate about and has a deep knowledge of the battles, the bush and Zulu culture. He has written numerous articles on military subjects and militaria collecting for overseas publications, has contributed to several books and is currently busy with his eighth book. His wide ranging knowledge and over 20 years guiding experience and unique story telling will bring events alive to his listeners. His books “What REALLY happened at Rorke’s Drift?” and on Isandlwana and Talana have gone into a number of reprints. He is a collector of militaria with special focus on medals. He also organises and conducts tours around the battlefields of KwaZulu-Natal and tours into Zululand to experience traditional and authentic Zulu culture and life style. Pat is currently the Chairperson of the Talana Museum Board of Trustees and one of the volunteer researchers.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.