Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Readers will no doubt be puzzled by a supposed mining link connecting Cape Governor Simon Van der Stel (1639-1712) to US President Herbert Hoover (1874-1964). They not only lived in different centuries, but also on separate continents 12 700 kilometers apart. Well, read on and decide for yourself!

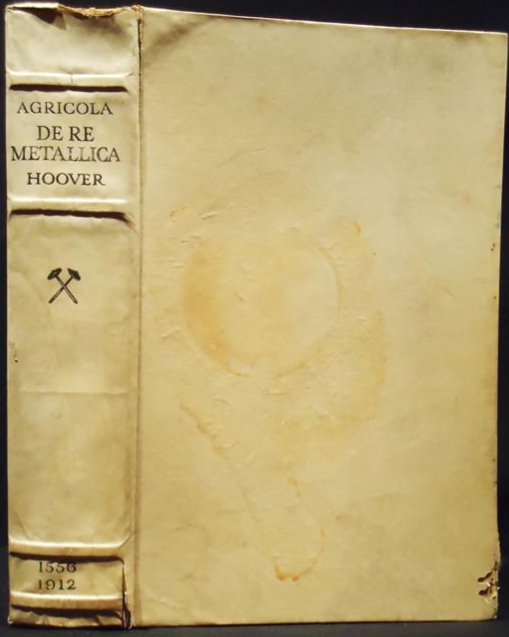

Our story starts with a book, not just any book, but the ‘De Re Metallica’, which collectors of rare books and Renaissance historians will recognise as the first printed book on mining and metallurgy. Written by Georgius Agricola (1494-1555) and published by Froben in Basel, Switzerland in 1556, shortly after the author’s death. This book was considered so important it went through three subsequent Latin editions between 1561 and 1657, three German editions between 1557 and 1621 and one Italian edition in 1563, at a time when the printing of such a specialised volume was no ordinary event.

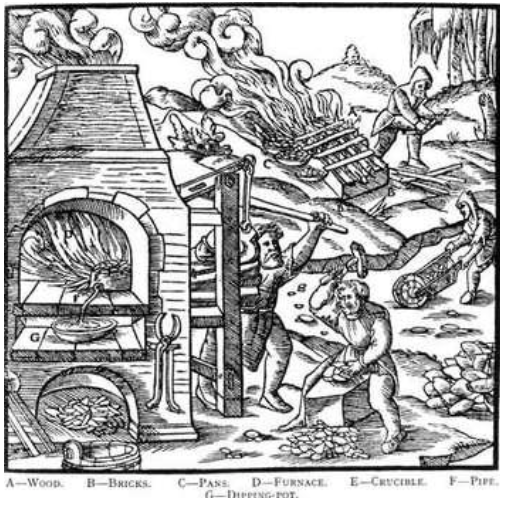

The ‘De Re Metallica’ (On the Nature of Metals) was the first book on mining and metallurgy to be based on field research and observation, containing 273 woodcut drawings and comprising several hundred pages. Much of the technical information provided by Agricola was either new or had not been given previously in enough detail to enable miners or craftsmen to perform the mining and metallurgical processes without further guidance. Agricola acquired the knowledge detailed in his book from personal experience and observation and it took him more than twenty years to complete this book. For almost 200 years it remained the only authoritative work on these subjects. It is said that until relatively modern times it was the work most referred to in the literature of mining and metallurgy and only its Latin text prevented it from being more widely known and quoted in the English-speaking world. However, at the time it was written most well educated people were proficient in reading Latin.

At present, an original 1556 edition of the ‘De Re Metallica’ would probably cost in the region of R800 000-R1 000 000, subject to condition and provenance.

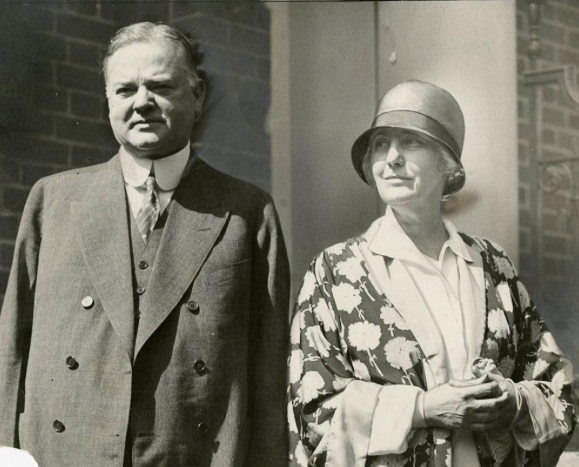

This is where Herbert Hoover (1874-1964) and his wife Lou Henry Hoover (1874-1944) enter our story. Most people are vaguely aware that Herbert Hoover was the incumbent Republican US President, elected in 1929, and convincingly defeated by the Democratic challenger Franklin Delano Roosevelt during the 1932 Presidential Election, because of his failure to resolve the 1929 Great Depression. Roosevelt went on to serve an unprecedented four terms as US President only to die in office shortly after being elected to his fourth term and mere months prior to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945.

Herbert and Lou Hoover (Source Hoover Presidential Library)

But it would be an injustice if this is all we recall of Herbert and Lou Hoover.

From a poor Quaker background, Hoover qualified top of his class in Engineering at the newly built Stanford University in California, where he also met his future wife Lou Henry who became the first female graduate in geology. Hoover subsequently achieved international prominence as a mining engineer in the USA, Australia, Burma, China, India and Russia. He also visited South Africa in 1904 to inspect a coal company and some gold mines under management of Bewick, Moreing, of which he was a director. Hoover would have become one of the global wealthy elite had he not decided to focus his efforts and energies on public service following the outbreak of the First World War. Hoover lived by the Quaker dictum that public service is a God-given privilege, not a business. Early in the war he became aware that millions of Belgians and Frenchmen trapped between the occupying German armies and the opposing Allied forces faced imminent starvation since their means of livelihood had been destroyed by the fighting in Flanders and the British naval blockade against Germany prevented the importation of food to assist. In what would become the first large international food relief operation, Hoover set up the Commission for Relief in Belgium and served as its head and on all other subsequent public service functions on a pro bono basis. The success of the Commission was due to the strong cooperation between Hoover and his Belgian counterparts and his ability to deal impartially with both the Allied and Axis Powers to ensure much needed foodstuff reached the starving masses.

Relief shipment of food by the Commission for Relief in Belgium (Cairn.info)

After the Armistice in 1918, Hoover, a member of the Supreme Economic Council and head of the American Relief Administration, organised shipments of food for the starving masses in Central Europe. He and his team fed millions of people in many countries and earned him the soubriquet of ‘The Great Humanitarian’. Elected US President with an overwhelming majority and were it not for the outbreak of the Great Depression, he would probably be honoured today as one of the greatest statesmen of the 20th century.

News breaking of stocks crashing on Black Thursday 24 October 1929 (Via the Guardian)

Spare a thought for Herbert Hoover who as US President had to deal with the greatest global economic meltdown in history, at a time when the prevailing economic theories and instruments were unable to predict, explain or remedy such hugely anomalous economic conditions.

US Soup Kitchen during the Great Depression – did not provide much to eat but better than starvation (Bettman/Corbis/Getty).

The US Federal Reserve System had been established only as recently as December 1913 and John Maynard Keynes still had to publish his ground-breaking opus, ‘The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money’. This book published in February 1936, set the framework for modern day macroeconomics and provided the intellectual underpinnings for Roosevelt’s ‘New Deal’. Keynes’ approach was a direct challenge to the belief of classical economists that market economies were always self-correcting and would when unstable, return to full employment relatively speedily. Keynes argued that free markets, left to themselves, do not always deliver the optimal good to society and when employment stagnated as it did catastrophically during the Great Depression, government must increase its deficit spending to offset shortfalls in total demand.

John Maynard Keynes (Economist)

But all this lay in the future. Our story focusses on 1912 when Herbert and Lou Hoover translated into English a complete and unchanged reprint of the ‘De Re Metallica’. This was published in a limited edition by The Mining Magazine, London, in a large and elegant format bound in white vellum (calves leather) like the original Renaissance edition and reproducing the original woodcut drawings and initial letters. This valuable book signed by both Herbert and Lou Hoover, was snapped up by antiquarian book collectors and dealers as well as historians of the Renaissance and Medieval periods who discovered it contained much of interest. This translation was also an improvement in that it contained numerous explanatory footnotes by Hoover, which the original lacked.

Translating the ‘De Re Metallica’ was a considerable achievement for, as the authors state in the Preface, Agricola had written his book in Latin which had ceased to develop a thousand years prior and Agricola therefore had to create several hundred Latin terms to express the mining and metallurgical technical expressions detailed in his book. Previous translators were unable to overcome this hurdle as the poorly translated 16th century German editions confirm. However, the combination of Herbert Hoover’s considerable mining expertise and Lou Hoover’s extensive knowledge of languages, including Latin, German and Italian, overcame this seemingly insurmountable barrier and jointly they were able to determine the intended meaning of those invented Latin terms and find suitable English expressions.

At present, an original copy of the Hoover edition of 1912 would probably sell in the region of R30 000 – R40 000, subject to condition and provenance.

The original Hoover translated edition of the De Re Metallica published 1912. This copy had a bookplate of ‘Vergenoeg’ – the library of Alpheus Fuller Williams with an inscription, ‘To Gardner F. Williams, Esq, with compliments of H. C. Hoover.’ (Antiquarian Auctions)

This in turn is where Simon van der Stel and the Journal of his expedition to Namaqualand from 1685 to 1686 enter our story. Van der Stel was appointed by the ‘Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie’ (VOC), as the eighth Commander of the Cape in October 1679, promoted to Governor in June 1691 and retired to his farm ‘Constantia’ in 1699.

The VOC was formed in 1602 because of pressure from the Dutch States General forcing all the Dutch companies trading with the East to amalgamate. Under its Charter obtained from the States General, the VOC could build fortifications, establish armies, declare war and annexe territory, in brief behaving as if it were an independent state.

It is interesting to note that had the Dutch not failed twice to take the Portuguese way-station of Mozambique Island (1607 and 1608), they may not have founded a victualling station in 1652 at the Cape of Good Hope. The Dutch expansion across Africa and the Indies during the first half of the seventeenth century was as remarkable as the overseas expansion of Portugal and Spain a century earlier.

Born in Mauritius, Van der Stel accompanied his parents to Ceylon (Sri Lanka). After his father was killed by the Sinhalese he travelled to Batavia (Indonesia) where he remained until 1659. He returned to Amsterdam in 1660 to further his studies but whether he did so is unclear.

‘The Night Watch’ of 1642 by Rembrandt gives some idea of the dress code during the Van der Stel era although the warmer weather at the Cape would have necessitated some changes (Wikipedia).

Arriving at the Cape, Van der Stel soon proved to be an energetic and conscientious leader, visiting the Hottentots-Holland region on horseback and establishing the hamlet of Stellenbosch in November of the same year. During the first half of his term of service he was very attentive to the development of agriculture and forestry.

In 1685, Hendrik van Reede tot Drakenstein, a special High Commissioner appointed by the VOC, spent three months at the Cape before proceeding to the Indies to advance its interests there. Van Reede was a well-read and refined individual who co-authored the twelve-volume luxury folio publication, ‘Hortus Indicus Malabaricus’, which became a standard work on the botany of Southern India. In this extensive publication containing 794 superb engravings of trees, shrubs, plants and herbs, the name of each specimen detailed in Latin, Malabari, Arabic and Sanskrit. According to the French scientist Tachard, Van Reede intended to also complete a ‘Hortus Africanus’. Van der Stel himself was also very interested in botany and one may well imagine him and Van Reede discussing botanical and mining matters pertaining to the Indies and to the Cape. Van der Stel subsequently named the Drakenstein area at the Cape in honour of Van Reede.

Van Reede authorised Van der Stel to lead an expedition in person to the land of the Namaquas, partly to cultivate friendly relations, partly to discover more about the fauna and flora of the hinterland, but mainly to discover the origin of the copper ore previously presented by the Namaquas and to investigate whether such ore could be commercially exploited. Another reason may well have been to determine the whereabouts of the fabled Kingdom of Monomotapa and its mythical city of Vigiti Magna. During the expedition the Namaquas spoke of a deep and rapid flowing river called Eyn, which the Dutch in turn called the Vigiti Magni. This was most likely the Orange River which remained undiscovered by Europeans until 1760, when it was crossed by Jacobus Coetsee, a White hunter.

Alleged painting of Simon van der Stel attributed to Pieter van Aenredt, Dutch Baroque era painter (SA History Online).

The above painting surfaced a few years ago and is alleged to reflect Van der Stel with a basket of grapes. According to the Dictionary of South African Biography there is no extant painting of Van der Stel, but it may not be the final word on the provenance of this painting.

The official record of Van der Stel’s great expedition to the Copper Mountains of Namaqualand was removed from the VOC’s Archives in 1691 or 1692. All trace of the manuscript was lost until 1922 when it was identified by Gilbert Waterhouse in the Catalogue of the Fagel Collection, acquired by Trinity College, Dublin in 1802. Baron Henry Fagel, Secretary to the Dutch States General, transferred his archival collection of about 20 000 items and documents to England in 1794 when Holland was invaded by the French revolutionary army under General Jean-Charles Pichegru. In 1802 Fagel arranged with Mr. Christie to sell his collection by auction, but instead the entire collection was purchased for the Trinity College, some time prior to the auction was supposed to take place.

According to Waterhouse, the Trinity College document may the only surviving manuscript of Van der Stel’s journey to Namaqualand. Another version was published by Francois Valentijn in 1726 in his ‘Beschryvinge van De Kaap de Goede Hoop …’ which may have been provided by Willem Adriaan van der Stel to Valentijn. The text of the Trinity manuscript is more condensed than the Valentijn version and it seems that the Trinity manuscript may be the carefully edited official report. Regrettably, the manuscript referred to by Valentijn is now deemed lost.

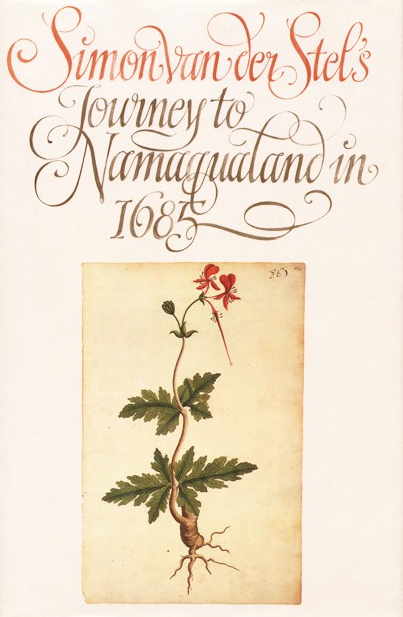

In 1932 the Dublin University Press printed the Dutch text together with an English translation, entitled ’Simon van der Stel’s Journal of his Expedition to Namaqualand 1685-1686’. In addition to the record of the journal, this edition contains seventy black and white photographs of the drawings attributed to Hendrik Claudius. Claudius had previously completed executed similar drawings on an earlier expedition in 1683, under the leadership of Lieutenant Olof Bergh.

Title page of more recent edition of Simon van der Stel’s Journey to Namaqualand (Antiquarian Auctions)

Although there had been previous mineral exploration attempts by the colonists in the Cape, this expedition led by Van der Stel was a major undertaking. Departing on 25 August 1685, the expedition consisted of 57 men, one Dain Mangale a Prince of Macassar with his servant, and three Black servants of Van der Stel. The baggage train consisted of one carriage with horses, eight mules, fourteen riding horses, two field pieces, eight carts, seven wagons of which one was loaded with a boat. This expedition lasted almost exactly five months to the day and journeyed as far as the present town of Springbok and back.

Frederick Mathias van Werlinckhof, the VOC’s Chief Mining Engineer together with some of his Dutch miners, accompanied Van der Stel and had to report on the mineral potential at the Cape, while en route to the east to assume command of mining operations on the west coast of Sumatra. Van der Stel’s journal does not mention the ‘De Re Metallica’ but since it was an official report of the expedition, it is not to be expected. It is likely that either Van Reede or Van Werlinckhof would have possessed a copy of the ‘De Re Metallica’. If they did not have a copy on hand, Van Werlinckhof as a seasoned mining engineer would have been very familiar with this book having studied it during his engineering studies. Van Reede as a gentleman of high learning would also have been familiar with this book. It is also very likely that prior to the expedition leaving Cape Town there would have been detailed discussions involving Van Reede, Van der Stel and Van Werlinckhof on what processes were to be applied in the prospecting for and assaying of mineral ore and what mining tools were required to ensure the success of the expedition. It is also more likely than not that the three would have discussed how the ore would be mined and transported, if proven to be commercially viable. During the course of these discussions some of the woodcut illustrations in this book would have been shown around the table as examples of how mining processes were to be implemented. We can also assume Van der Stel and Van Werlinckhof would further have discussed techniques of mining during their long journey to the north and back.

Van der Stel’s prospecting shaft at Carolusberg, Springbok Northern Cape (Wikipedia).

The expedition reached the Copper Mountains on 21 October 1685 and pitched camp close to the present town of Springbok. Three small prospecting shafts were sunk, one of which has been preserved as a national monument. Unfortunately, the samples they selected and sent to Holland for testing proved to be disappointingly low in copper content. The expedition had passed within a stone's throw of some of the richest outcrops of copper in Namaqualand. Had they prospected two kilometers or so towards the south-west, commercial copper mining in Namaqualand may have occurred much earlier.

Of course, the distance from Cape Town to Namaqualand and the harsh terrain proved to be further barriers to exploiting the copper ore and Van der Stel and his party failed to find a suitable harbour on their journey back down the coast.

It was ultimately decided that the discovery would have to be abandoned for later generations to develop.

Main image: Woodcut illustrating extraction of metal from ore in ‘De Re Metallica’ (Source Brittanica.com).

About the author: SJ De Klerk held many senior positions in HR during a distinguished career in the private sector. Since retiring he has dedicated time and resources to researching, exploring and writing about South African history.

Bibliography

- Agricola G. (1950) De Re Metallica. Translated by Herbert Clark Hoover and Lou Henry Hoover. Dover Publications Inc., New York.

- Agricola G. (1961) De Re Metallica. Deutsches Museum von Meisterwerken der Naturwissenschaft und Technik. VDI-Verlag G.m.b.H Dűsseldorf.

- Boxer C. R. (1977). The Portuguese Seaborne Empire 1415 - 1825. The Anchor Press, Essex.

- Davenport J. (2013). Digging Deep a History of Mining in South Africa. Jonathan Ball Publishers, Johannesburg.

- De Kock W. J. Editor. (1976). Suid-Afrikaanse Biografiese Woordeboek Vol I. Raad vir Geesteswetenskaplike Navorsing. Tafelberg-Uitgewers Beperk, Kaapstad.

- Dickson G. B. (1978). Cornish Immigrants to South Africa. A. A. Balkema, Cape Town.

- Greenspan A. (2013). The Map and the Territory. Risk, Human Nature, and the Future of Forecasting. Allen Lane.

- Greenspan A. (2007). The Age of Turbulence. Allen Lane.

- Keynes J. M. (1946 Reprint). The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. Macmillan and Co. Limited, London.

- Lyons E. 1964. Herbert Hoover A Biography. Double Day & Company Inc., New York.

- Schoeman K. (2009). Handelsryk in die Ooste. Die wêreld van die VOC, 1619-1688. Protea Boekhuis, Pretoria.

- Waterhouse G. (1932) Simon van der Stel’s Journal of his Expedition to Namaqualand 1685-6. Dublin University Press Series.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.