Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

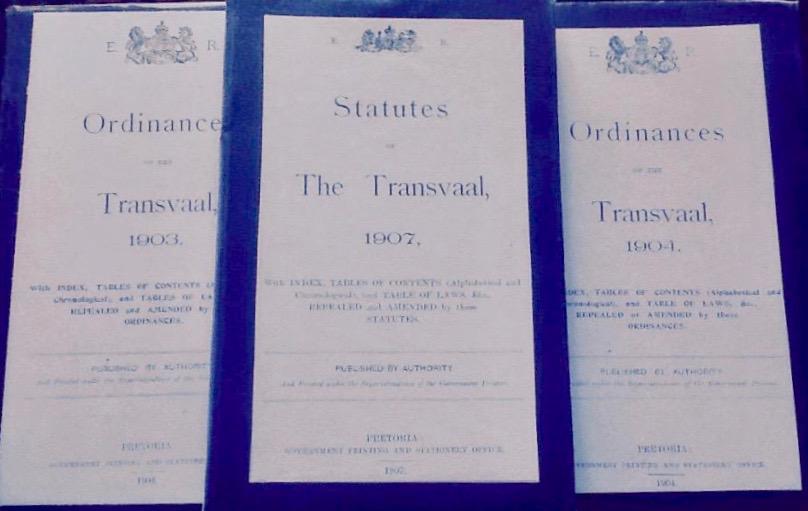

Ordinances of the Transvaal 1903, 1904 and Statutes of the Transvaal 1907. Whoever wants to look at old, dry, dusty, obsolete law books? Law books date, they take up space on shelves and laws are repealed. Legal language is precise and unemotional. The Transvaal ceased to exist in 1994 and today a completely different provincial government structure has replaced the pre 1994 arrangement of four all white driven apartheid provinces and the 10 bantustans.

But step back in time and old law books acquire an antiquarian and historical interest and become yet another prism through which we can attempt to understand the past. Laws, ordinances and statutes are building blocks of an orderly society. They are an expression of the norms and values of a society at a particular point in time. Laws embody the canons of justice. They give authority to the executive arm of government in matters large and small. A society without law shifts into an anarchic state. Laws enable government to implement policies, ideologies and principles. Law gives expression to changed circumstances in societies.

It is the bread and butter of lawyers to read law books but the layman can broaden his reach and grasp by also trying to read a law book or two.

I recently dropped in on a sale of a deceased private collection of Africana and history books. Buying three old law books dating back to the early 20th century was not my first choice as I gathered up a miscellaneous but appealing selection of books. At R40 for a hard cover here was an opportunity not to be missed. Then on my second drift past the rapidly thinning shelves, I found myself drawn to these volumes on the old Transvaal. I paged to the index and immediately it was evident that these volumes were important. The volumes, read as a body of legal work give an insight into a new society in the making as the Transvaal Colony came into being under British Administration and the old defeated Zuid Afrikaanse Republiek dropped into history. Here is the raw material for the study of transition from Boer administration to colonial British management. Of particular interest are the laws and rules relating to Johannesburg. The three volumes joined my selection of purchases.

On returning home my first question was how readily available these sorts of books are and indeed I found a few possibilities. One can purchase Ordinances of the Transvaal 1904 from Bookdealers of Melville for R600 and sure enough this was a copy that originally belonged to the University of the Witwatersrand, so it is an ex library copy. Second choice is to purchase a newly made to order reprint from Loot for R746 based on the digitized version of Harvard University. If Wits no longer values the colonial, Harvard certainly does. Or a third possibility was to open the online wired place library resource of the University of Pretoria to access their digitized copy (it is a very large file). I was delighted with my decision to purchase these old volumes that over a hundred years have passed through the hands of at least two or three owners. I suppose it is horses for courses. These are reference books that were consulted daily by lawyers and judges to implement law and create precedent. Of course after 1910 many of these laws were subsumed by the Union of South Africa and statute making by the independent new dominion government. This is what makes the period 1902-1910 such an unusual one, as it was the period of colonial administration; the Transvaal was a crown colony under the suzerain of Edward VII. These law books capture the aftermath of war, the coming of peace, the return of people to their homes, the reconstruction of the Transvaal and the revival of the gold mining industry.

What is the value of these specific old tomes? It seems that the price tag for a volume is between R600 and R800 but value is what someone is prepared to pay and whether the Guttenberg or Harvard University digitizers are of the opinion this is something important that adds to human knowledge and should be reprinted. These criteria apply in the case of Colonial Transvaal ordinances.

In 1900 Johannesburg was occupied by the British army and in 1902 the Anglo Boer War came to an inglorious end when the South African Republic ceased to exist. The Transvaal and the Free State passed into a period of direct British administration and military occupation. The Transvaal Colony was the new name and as mentioned Edward VII was the King. It was a relatively short period of direct British rule, as in 1906 responsible government was given to the Transvaal and a legislative council of 15 members was established. The physical borders of the Transvaal Colony were not identical to the defeated South African Republic, but larger. In 1910 the Transvaal Colony became the Transvaal Province of the Union of South Africa.

Plaque commemorating the British occupation of Johannesburg (The Heritage Portal)

The British coat of arms with the neat small capital letters, E R (Edward Rex) heads the title page. It is an interesting period of South African history as the Edwardian decade was one of reconstruction and repatriation. It was a time of economic revival and a building boom in Johannesburg (though the immediate post war period saw a short depression). These documented ordinances detail the framework of government and give a sense of the issues of importance. It is fascinating to read about the business and busyness of government in matters large and small. Hence the 1903 ordinances cover a diverse range of activities - liquor licenses, criminal procedures, explosives law, mining rights, customs duties, trigonometrical survey, wills, bail in the magistrates courts, railway police, inquests, military manoeuvres and expropriation of land. Civil life and the return to normality is shown in subjects like public holidays, marriages and public education. Judges' pensions were efficiently arranged. In some ways all this legal framework is utterly mundane, dense and boring but at the same time it is fascinating because it reveals the struts and building blocks of a new society and a new social order. It was a racially divided society as there were rules and separate laws for marriage of what is called “coloured persons” in the ordinance but “native marriages” in the index. Passes for natives also exercised the minds of the authorities. Here too were the legal efforts made to pacify the Transvaal, with the requirement that burghers swear allegiance to the king.

The famous Corner House was one of the buildings erected during the post war boom (Views of Johannesburg and Suburbs Album)

I zoomed in on the ordinances of direct relevance to Johannesburg. In 1903 elective municipal councils were legislated, putting into place mayors and town clerks. The powers of the Johannesburg municipality were stipulated. The voters comprised every white person male or female aged 21 and up who owned rateable property within the municipality. That is an interesting early women’s suffrage win but it was a colour based franchise. Note also the restrictions to white property owners in the Transvaal. In 1903 the Rand Water Board was established; the Johannesburg municipality was given certain borrowing powers.

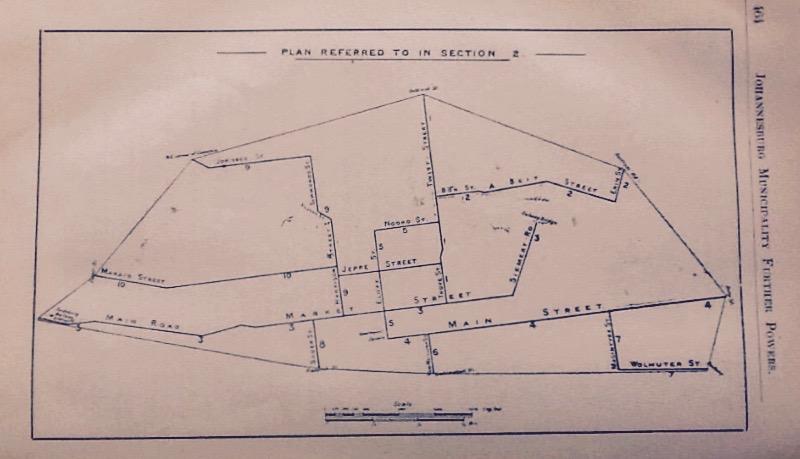

1903 was the year Johannesburg was given the powers to initiate a tramway system with horse drawn trams, commenced in 1905. There is a schedule which includes a plan showing the projected tramway routes. This is an essential item of urban data as it shows that tram routes were planned to run to Braamfontein, Doornfontein, Hillbow and eastward on Main Street towards Kensington.

Projected tram routes

The 1903 volume of Ordinances is particularly dense and makes for fascinating reading on just about every subject that mattered in the post war recovery period, with a clear plan of how to improve government in the colony.

The 1904 ordinances deal with stock branding, cattle diseases, stock theft, trademarks, rabies, companies law, coinage, the census, preventing plant diseases, fending, fish preservation and so much more. Johannesburg’s affairs feature in the validation of the Rand Plague committee acts, the Rand water board powers, the operation of the Johannesburg municipality. Perhaps most significant in that year was the ordinance to allow for the importation of Chinese Labour; this was the great scheme of the Chamber of Mines and the Mining Houses to resuscitate gold mining on the Witwatersrand by importing indentured Chinese labourers.

Postcard of Chinese miners (A Johannesburg Album)

Early in 1906 the Liberal government of Campbell Bannerman came to power in Britain and was persuaded by Smuts to grant responsible government to the Transvaal, which was an effective prelude to the creation of the Union of South Africa in 1910. The upshot was the organization of an election in the Transvaal and the principal party was the Afrikaner Het Volk. The big issues of the day were that of Chinese indentured labour and its discontinuation and how to ensure that there was a buy in by the Afrikaners following pacification and hence ultimately reconciliation with Britain.

Hence by 1907 there is a shift from ordinances of a crown colony to Acts and statutes of the Colony of the Transvaal endorsed with the granting of Letters Patent and the provision of a constitution for functioning of the next stage of greater independence for the Transvaal.

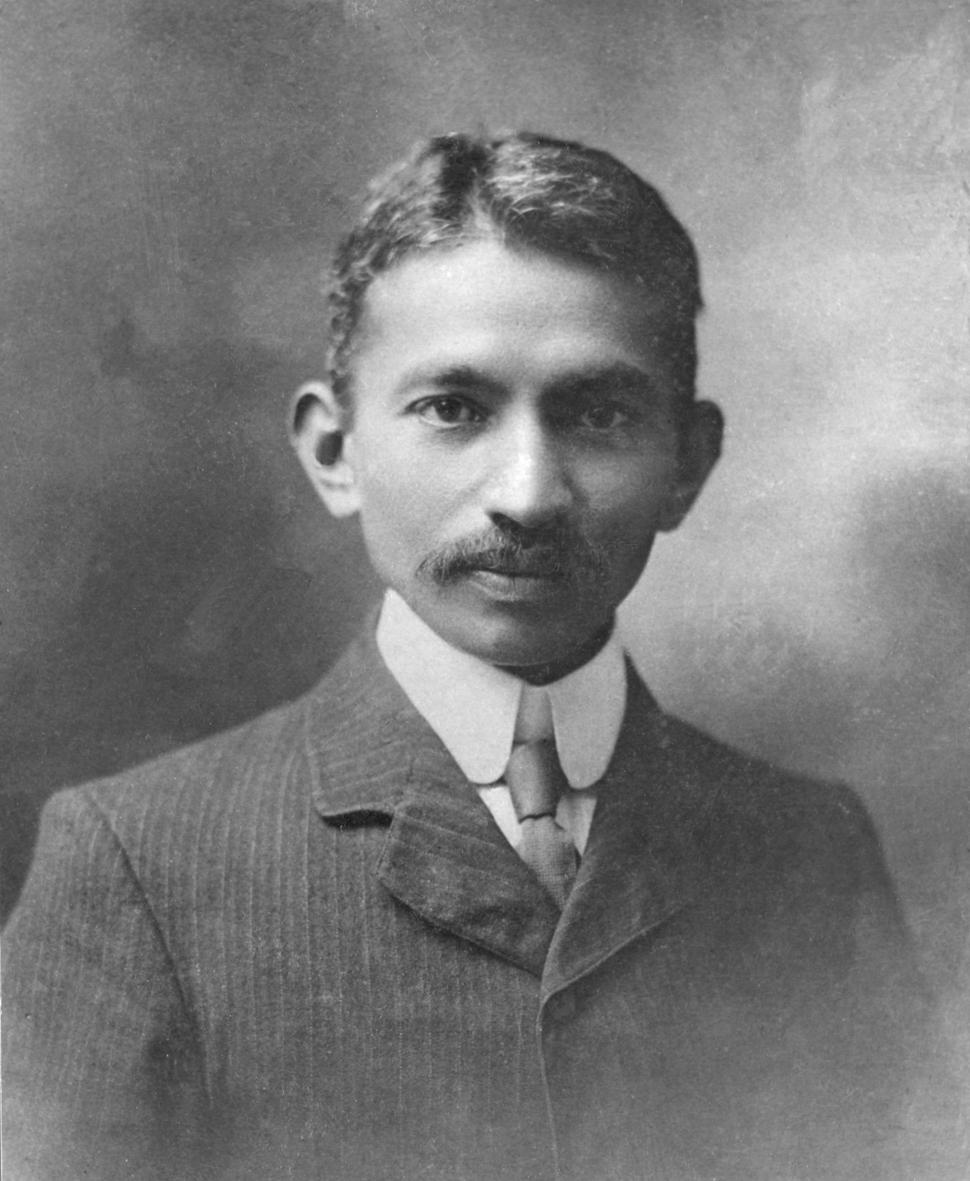

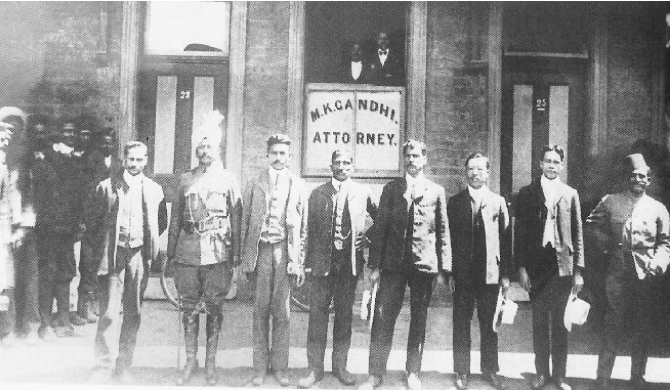

The 1907 statutes are of great interest because they show how the great issue of the day was handled, namely the management of labour. The Indentured Labour Laws were temporarily continued (but in the long run the Chinese indentured labourers were to be repatriated) and addressing the issue of the registration of Asiatics (or Indians and Chinese people) in the Transvaal requiring their registration. Thus Act no 2 of 1907 which took effect on 1st July 1907 amended the Volksraad Act of 1885, stated that every “Asiatic lawfully resident in this Colony shall be… registered in the register of Asiatics and shall be entitled to receive a certificate of registration”. It was this legislation (and the early 1906 ordinance) that inflamed and inspired Mohandas Gandhi to reinvigorate the fight for civil rights for Asiatics (which included Chinese people) in the Transvaal and gave impetus to his use of passive resistance or satyagraha and it was this act that led Gandhi to become the great adversary of Smuts. The advantage of reading the legislation is that you are then able to get behind the thinking of the day and probe the actual legal language minus the outraged interpretation and reaction that these laws gave rise to.

Gandhi in 1906

Gandhi third from left with Passive Resistance leaders in Johannesburg 1908. Photograph via Transvaal Leader Weekly 11 January 1908

All the other topics legislated on pale into insignificance with the big political hot potatoes of race governance and ethnicity but they are all there all the same. They show the rhythm of daily life - the themes of arms and ammunition, cattle diseases, excise, education, field cornets, game preservation, a land and agricultural bank, leprosy laws, patents, land settlement, paying members of parliament and the Pretoria Municipality affairs amongst others. In 1907 there were 36 pieces of legislation. One item of relevance to Johannesburg was a 10-7 act amending the Vrededorp Stands Ordinance Act of 1906. It enabled freehold land ownership and title in Vrededorp but unfairly denied Asiatics or coloured persons the right to acquire freehold land rights. Here we see the deep roots of disadvantage and inequity and impoverishment of urban people based on race.

This type of document then becomes a primary research source and gives clues to who owned what where and why race created conditions for disparities that remained with us for nearly another century.

Acquiring Transvaal Ordinances and statutes for these specific years enables the researcher to drop in on Transvaal society as it was being made for a new century. Laws are directives and organizational devices to promote a peaceful, progressive and organized society but one where values, norms and ideologies shape how discrimination was embedded in law. These are documents to be read with an analytical eye and to be read above, below and between the lines. It’s a treat to read a primary source before turning back to a standardised summary of the decade. Cut through the legal language and understand that these were the laws that shaped the lives of our ancestors.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.