Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Once, a train ran from Port Alfred station every day: the 11.10 to Grahamstown, 68km away. In the early 1900s the train used to steam up through the valleys towards Bathurst and Grahamstown taking farmers, farm workers, holidaymakers and commercial travellers, especially on stock-fair days, when the atmosphere was festive and the coaches were full. It is no longer possible to go on the train. One must walk the line or take the road that loops and meets, strays from and returns to it.

The railway runs truer than the road: there are fewer meanderings and distractions. In the old days, prospective passengers could signal to the train driver if they wanted to board, running up from a farm or waving from the veranda of a homestead for him to wait. Train drivers were obliging in those days.

Mr. Robinson, driver of the 11.10 on Saturday April 22 1911, was aware of potential passengers as he steamed along. By the time he reached Martindale, he had 52 on board. The line was built in 1883, tracing a wide curve across the farms of lower Albany, ancient in the history of the indigenous people long before the first white colonists settled there in 1820. The names of the small stations and sidings are testament to the provenance of those Settlers: Hayes, Bathurst, Clumber, Trappes Valley, Martindale, Manley Flats, Oak Valley, with the occasional gesture to other origins: Blaauwkrantz. The older, Xhosa names for the rivers that cross those grass and copse-scattered hills are unrecorded in colonial records.

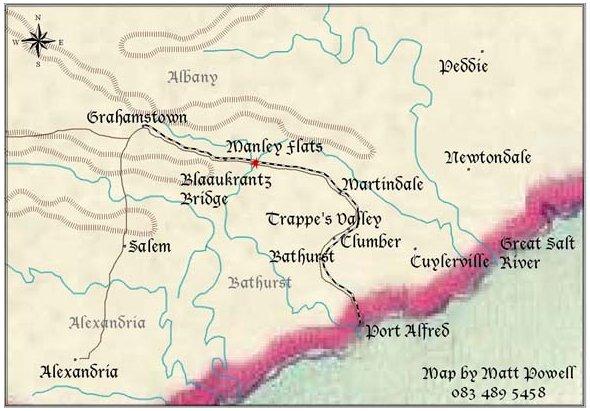

The route from Port Alfred to Grahamstown (Matt Powell)

Blaauwkrantz is the destination of this journey, although it is not at the end of the track. It is the place of other ghosts. There is a limpid quality to the air in this quiet corner of the Eastern Cape, shrikes calling, proclaiming territory, the blue-black bush marking out the camps where cattle graze. The hills are low. There are lands cleared for pineapples and chicory. Far off, the sea is glimpsed between bushes trailing orange Tecoma, blue here and there with Plumbago.

The first real station is Bathurst. It was once an important destination thronging with passengers. Now but a ghost of days gone by. From here the line loops out, heading east past the sidings of Purdonton and spring Grove to Clumber. A small white church and school stand on a grassy knoll among old trees and quiet graves.

Clumber Church (via the Clumber Church facebook page)

Trappes Valley station is derelict under a pale sky, and here we are furthest east in the journey. This is frontier country. Out there, further than the horizon, is the Great Fish River and Coombs, where the sacred clay pits of the Xhosa were found.

The tollhouse is derelict now. An aloe has taken root on the walls of the upper gable. Beyond the broken walls you will find a grove of Mtsintsi trees where - legend has it a besieged farmer had his hand pinned by a spear to a sneeze-wood post as he reached to take a loaded gun. His adversary was his long defected herdsman.

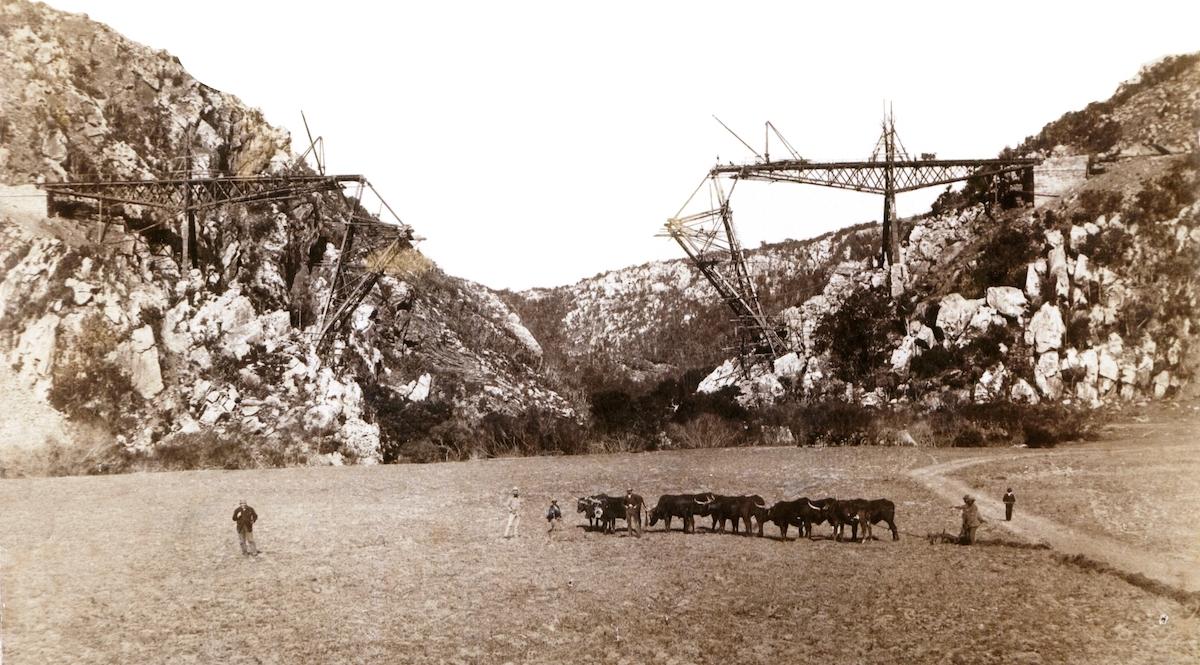

There is a well in a grove, perfectly preserved. At Martindale there are people living in the old guard house. A scarecrow made from an overcoat crucified on sticks, his head a rusted paint tin turned upside down, guards a mealie patch. There are neither mealies to guard nor birds to chase away. From Martindale the rail swings northwest again. The country is more broken. Surveying the possible route for the railway line in the early 1880s, the railway engineer George Pauling wrote: "A very bad piece of country had to be crossed and it took some time before it was decided to cross the worst spot on the route called Blaauwkrantz, about 21km from Grahamstown, by a high level bridge."

A very bad piece of country had to be crossed (P Hall)

A very bad piece of country indeed. At the bottom of the gorge there is a large pool. It is one of a number of pools scattered randomly throughout the Eastern Cape where the "People of the River", Abantu Bomlambo, are thought to reside. In Xhosa cosmology, the People of the River are believed to live beneath the water with their crops and cattle.

It is they to whom initiates go when they are called to be diviners and who may sanction their vocation. Those they approve may be lured into the depths of a pool to join their society for a time. Those they reject drown. Libations and gifts for the Abantu Bomlambo are often floated out into the centre of the pool in small baskets containing sorghum, tobacco, pumpkin seeds, white beads, a calabash of beer or brandy. Small wonder then that the Blaauwkrantz River, its pools and gorge registered anxiety in the more sensitive traveller from the earliest times. There is a sense of another existence here. This was a place of pilgrimage, a spirit domain, a place of brooding - long before April 22, long before the railway line was opened on October 1st 1884.

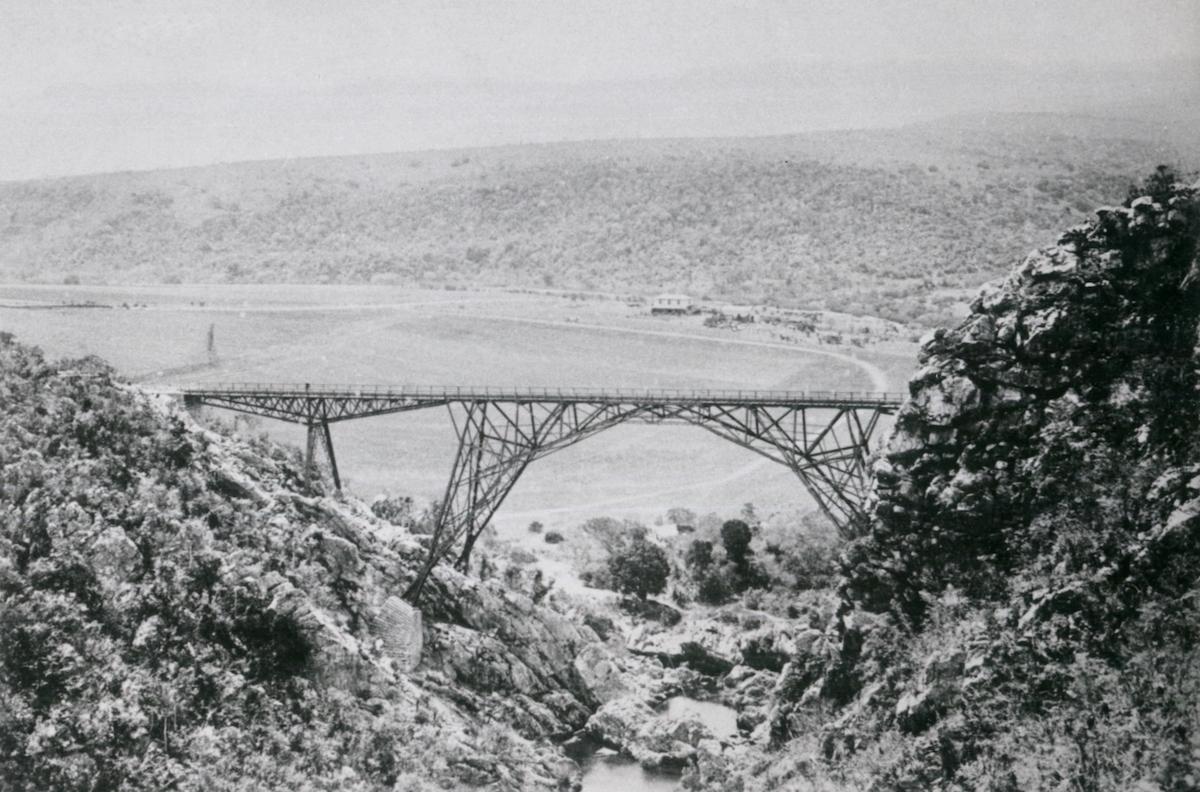

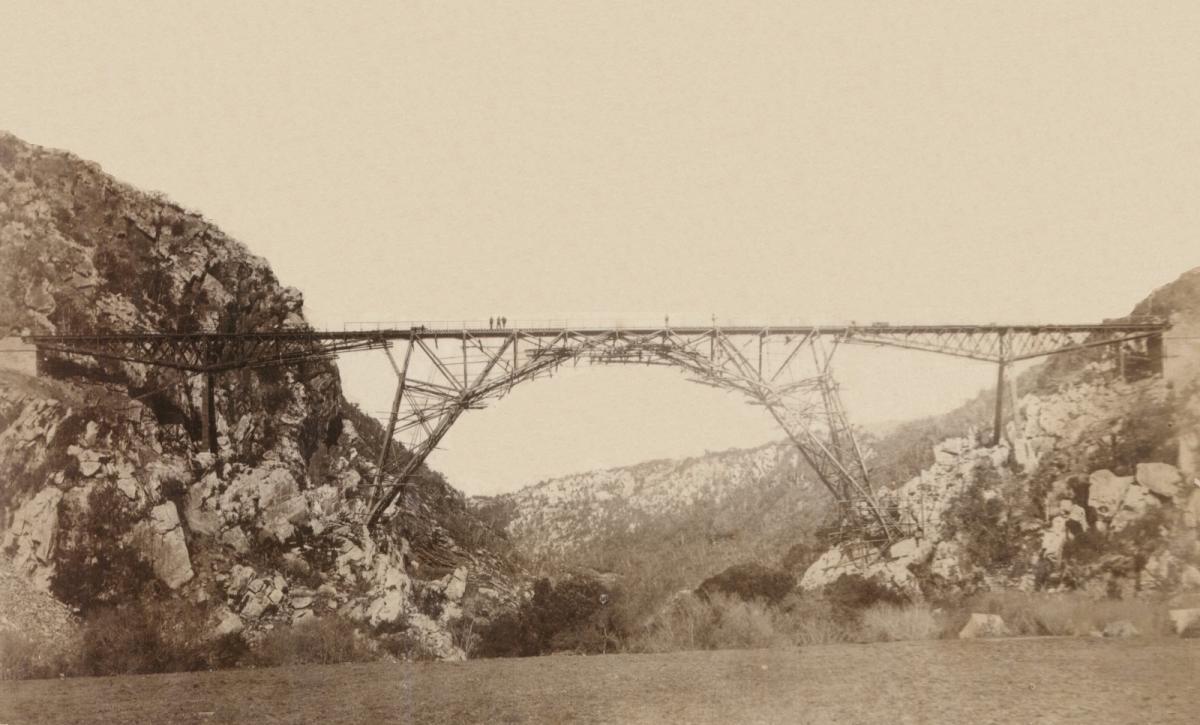

It was over the Blaauwkrantz Gorge, situated between two such pools, that Pauling built the bridge. Designed and constructed in England, the material for the bridge was transported from Britain by sea. It was assembled in 1883 and, when completed, was only 6mm out of specification: a beautifully calculated feat of engineering. Built light and strong, suspended web-like above the chasm, it could withstand the winds that often sweep down the tunnel between the cliffs. It no longer exists but, from old photographs, it had an airy, latticed appearance, vaulting the space between the kranses guarding the riverbed, the banks of which were planted at that time with the orange orchards of Leslie Palmer, owner of Brenthoek farm. Palmer's descendants, the Clayton’s, live there still.

Building the Blaauwkrantz Bridge

A little further along

An engineering feat

The completed bridge

The new bridge, built in 1928, sends its shadow out across their lands. The fence of the clay tennis court is supported by girders from the 1911 bridge. A ladder, constructed from the same, leans against the stonewall of an outhouse. Walking down into that gorge there is a feeling - quite apart from the knowledge of the history that was played out there - of the aloofness, the detachment of the landscape. Long before a road or bridge was built, it has been rumoured, early transport riders used to approach the place with some trepidation, while Africans on the journey would insist on waiting a time of placation before descending the slope.

The 'new' bridge (Bev Young)

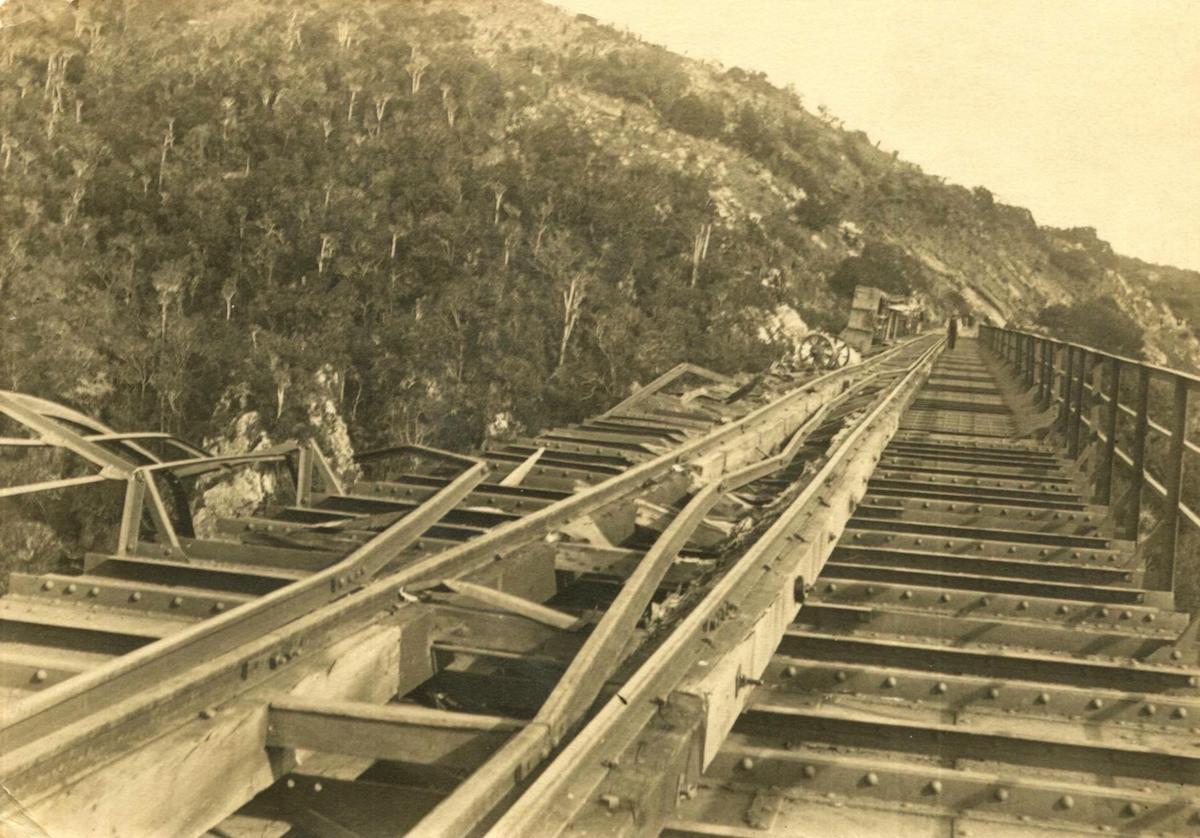

On April 22 1911, the train left on time. Behind the engine was a coal tender followed by five trucks of stone, from Bathurst, for the completion of the Grahamstown cathedral. A fifth truck carried a loose cargo of pineapples, that crop of lower Albany that spikes the lands with pale sage coloured leaves against mulberry earth. Four passenger coaches and a guard's van were coupled behind this, the black passengers crammed together in the last coach, en route to stock-fair day in Grahamstown. Two-thirds of the way across there was a sudden lifting and lightening of the load. The sound of metal, the flump of steel on steel, smoke and dust rising. The fourth truck had uncoupled. One can only guess at Robinson’s (the train driver) horror, at the moment of turning his head, and seeing the fourth truck rail-jump, fall on its side, the grind of steel as the passenger carriages and guard's van plummeted into space, the roof of one detaching, the last coach in which the black passengers were travelling, somersaulting once before it hit the rocks more than 60m below. The roof of a carriage spiraled down, providing a safer landing place for a passenger, a lampholder caught in the girders, a man's coat fluttering on a spar.

Debris from the disaster below the bridge (Japp)

An overturned carriage (Japp)

The aftershock must have echoed up and down that gorge, stunning Leslie Palmer in his lands with his labourers, one of whom, at the moment of the accident, had called out, "It is falling! It is falling!" The appalled driver, knowing there was nothing he could do to help, hurtled his engine, coal tender and two trucks towards Grahamstown, and whistle shrieking. The stationmaster of Grahamstown was out on the platform. With what dread must he have heard the long-approaching shriek of the whistle, seen the smoke, then the engine and truck without the coaches or the guard's van, the distraught driver stumbling from the cab.

It was not the bridge that had failed. The weight of the stone had not broken it. Some engineering experts said it was the age of the dog spikes and the repair of the rails, rotten sleepers, the vintage rolling stock too heavily laden. The stationmaster of Bathurst believed it was the shifting of the pineapples as the train took a curve, causing a stone truck ahead to jump the rails and overturn, obstructing the path of the following carriages so that they concertina, derailed and fell. Some said it was other forces: the Blaauwkrantz is not a gorge to challenge. Within an hour a relief train had reached the sight with three doctors, nurses and medical equipment. Among the first Grahamstown residents to arrive at the scene were a group of clergymen representing every denomination.

Bent rails after the disaster (Japp)

Among them was the Rev William Brereton (his daughter was one of the passengers). For him, the descent into the gorge must have been the most appalling journey of his life. And the longest. Hopie Brereton did not survive. Her father carried her body from the gorge. Grace Pike of Clumber did. But in the fall, the 22 pins with which she had arranged her hair so meticulously had pierced her head and had to be extracted one by one.

There is the well-known story of the miraculous escape of little Hazel Smith, who, with her sister Dorothy and three-year-old brother Willie, had been catapulted from the train window as it fell. Hazel was caught in the girders. Her sister Dorothy clung to the side of the bridge for some time. Then, unable to hold on, she fell. Baby Willie, whom Hazel had by the hand as he dangled precariously above the chasm, struggled violently. He too fell to the gorge below. Dorothy survived. Willie lived only a day.

Wreckage in the gorge below

The newspaper reports from the time are full of the language of drama, stories of bravery and courage. Absent from all of them is any description of the black passengers killed in the accident, except for mention of a woman whom rescue workers tried to free for many hours, only to die as she was taken up the gorge. The absence from the press reports of the story of that carriage full of passengers is reflected in a scrawled aside taken from an unpublished letter: An African woman being taken from Kowie Mental to Fort England was later found to be sane! A strange little silence hovers around these victims.

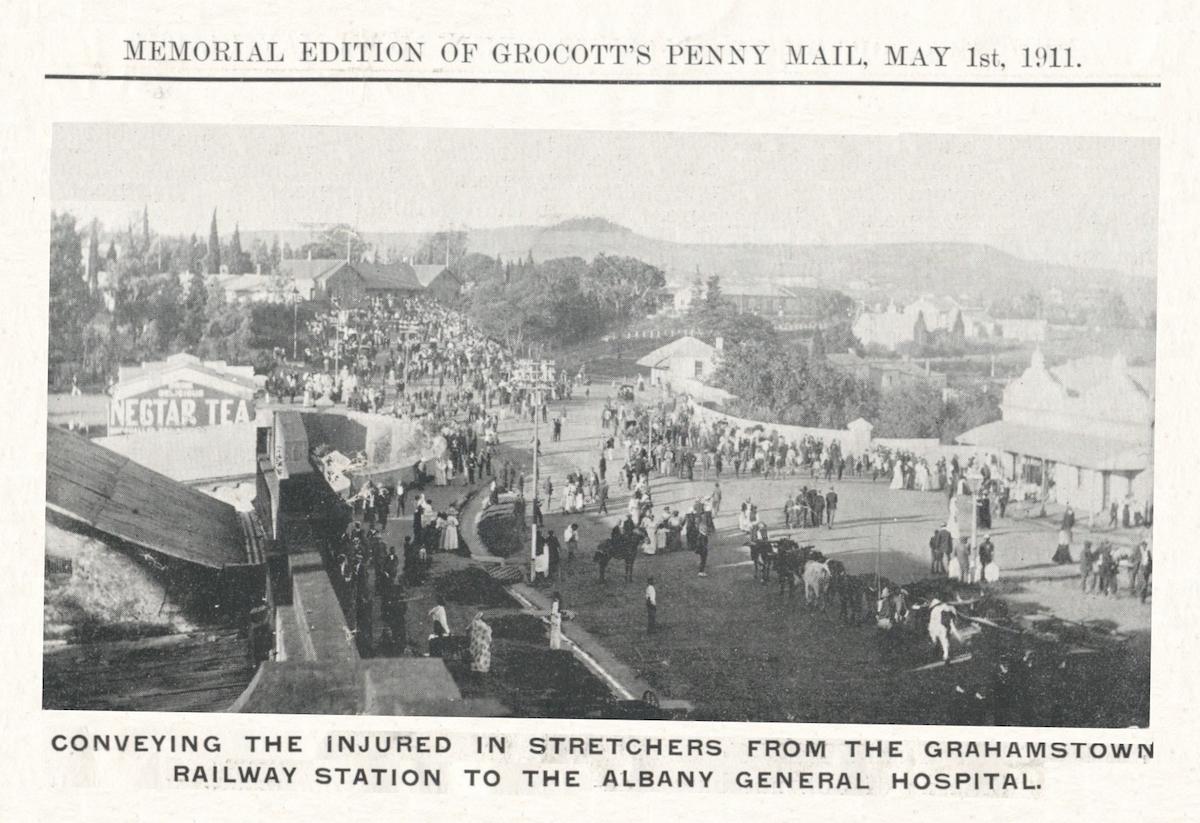

Injured arriving in Grahamstown (Grocott's Memorial Edition)

Another image from the Grocott's Memorial Edition

Altogether, 29 passengers died. Twenty-three were injured. At the time, the Blaauwkrantz Bridge disaster was the worst accident South Africa ever witnessed.

Bev Young is a prolific researcher and writer on Eastern Cape history. She has explored thousands of significant spaces and forgotten places across the province. Her archive of material is a priceless resource.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.