What is the purpose of a film? At the simplest level, it is a form of storytelling in visual form, satisfying an age-old desire of humans to gather to listen to the elders of a tribe relate as oral tradition, fables and myths, stories and heroic deeds. Films can entertain, educate, offer fantasy, and as a visual medium can thrill, scare and transport the viewer to another world. Film is a medium of popular culture. Film is a means of learning about other societies mediated through the imagination of the director. Films are also a form of reflection, an art form that enables modern society to hold a mirror to itself to reveal essence and sometimes unpleasant truth about our world. The challenge for any filmmaker today is to tell a story in a defined relatively short time span, expeditiously and in a given budget. Another challenge is to reach your audience in a structured distribution framework, where the marketing budget may well exceed the production costs. Film making is a risky business and it's tough to make your fortune.

Johannesburg's history is synonymous with moving pictures history and from the earliest days there was an appetite for showing films in bioscopes, picture houses and cinemas. Film quickly became part of the daily fare of people in a mining camp, town and then city wanting to imagine they were somewhere else. Parker makes the interesting point that Johannesburg is one of the oldest film making centres in the world, though that is hardly the basis of its reputation.

The central argument of this study is that film made in and about the city influences perceptions and knowledge of the city in the minds of residents. The thesis of Alexander Parker's sophisticated reflective study of film is that there is a particular tie between the city, and in this case Johannesburg, and the making and appreciation of film by the residents of the city. The author argues that urban film is a medium that helps people live in the city, bridge divides and make sense of their world. Film is significant in the life of people in a city in helping residents negotiate the pitfalls and obstacles of the inequalities and divisions of urban space and living.

Book Cover

The principal themes explored in this study cover Physical Materiality and Imaginability (this means exploring how the physical city of Johannesburg is represented in film), Identity (meaning the identity of filmmaker, character, neighbourhood and place and audiences), Mobility (Johannesburg as a destination for migrants and immigrants and how travel around the city is shown in film) and Crime and the City (this final chapter looks at issues of the city as a fearful place of criminality, fear and anxiety as portrayed in the film).

Although I.W. Schlesinger gets a one line mention I found the lack of an analysis of his work and influence surprising. For his era, he was a key Johannesburg film man. Another omission is the absence of any discussion of the old-fashioned newsreels. Pathe and SA Mirror (along with a cartoon) were integral to every movie screening. Today on You Tube one can search and rediscover those gems. Jamie Uys and his influence are also missed though perhaps one of the best known of South African movies was surely, The Gods Must be Crazy (1980). It was one of the most successful commercial movies in South African filmmaking though the location was Botswana. I also wondered if you can look at film without taking into account the influence too of the advertisements which were screened in movie houses... all those images of liquor, investment banking opportunities and at one time cigarettes. They too shaped perceptions and practice.

Urban Film has its origins in a PhD thesis at the University of the Witwatersrand. With the help of a post-doctoral fellowship, the research was converted into a book. The focus is film making in Johannesburg and how films about the city influence and impact on everyday practice of life and living. The study offers another dimension to our knowledge of Johannesburg and adds to the literature of the city, tackling a novel angle. The book is not a history of a film but rather an erudite academic study involving fieldwork and research across what is called "circles of culture", to establish the image of the city as produced in films.

This is a serious study of films made in and about Johannesburg. In a sense, it has a sharp, narrow focus but needs to take this approach to manage a large subject area.

There is an excellent filmography of Johannesburg films made locally from the very earliest days (1916) to 2015. The list covers 75 clearly must see films set in the city or of relevance to city people, originally made for big screen and large audience viewing, more recently for popular home screening or TV viewing.

Parker has clearly become a film buff and the authority on Johannesburg on film. She has diligently sought out Johannesburg movies, studied and now written about many of these films relating not only story lines but explaining what these films do to bridge cultural, social, economic and geographical divisions in Johannesburg. She sets a pace in a trail of rediscovery and revival of old movies. People get excited and connect when they see their city's landmarks as part of a film's backdrop. A glimpse of Ponte tower on the silver screen adds to its iconic status, as a defining point of personal identification. The mine dumps of the city add another distinctive landmark.

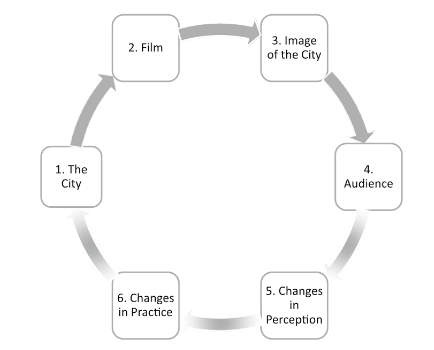

My interest was stirred enough to want to embark on a mission to try to see as many of the Johannesburg located films that Parker discusses but now with the advantage of using her erudite analysis to enhance appreciation and understanding. She is interested in how social inequalities and economic divisions in the city are portrayed in film. A neat circular diagram sums up the relationship of the city portrayed in a film, producing a mediated image that is viewed and understood by an audience and then results in a change in perception followed by changes in practice. That is quite a mouthful but it's what this complex and original study is all about.

Because this book originated in Doctoral research there is an attempt at a scientific methodology to measure perceptions and practices in this analysis of the influence of the film. A quantitative survey of 200 people was undertaken to test how images of the city created by film influences everyday living in the city and finally the author then tries to analyze the influence of film through qualitative interviews with 9 people and a focus group of 5. I wondered how reliable this methodology actually is to support the arguments about practice and negotiating city life.

As is to be anticipated in an academic study, each chapter is supported by a section of notes and references and a comprehensive very useful bibliography follows at the end of the book. I found the convention of inserting the source of a particular comment in the text with the name of the author makes for interruptive and disruptive reading. I would have advised a shift from a desire to impress an examiner to carrying the readership into the heart of the original arguments and insights of the author.

I found the perspective of this study particularly interesting in that it has come out of an urban studies locus, rather than a media studies department. The principal insight is that film in its many dimensions of production, acting, editing, screening and finally being viewed by the residents of the city is another medium through which one probes change in the urban environment. The author is herself interested in heritage and is an activist in heritage work in the city so is passionate about Johannesburg and this love of the city comes across in her specialist study of film.

As mentioned earlier, this book is not a history of film or film making in South Africa. For that one still needs to turn to Thelma Gutsche's now somewhat dated 1972 book.

There is nothing here about the architecture of the great cinema houses of Johannesburg, their rise and fall and transformation into the suburban mini screening venues in shopping centres aimed at multiple, segmented audiences. There is nothing about the economics of film making and the challenges faced by producers and directors to even get films screened and hence noticed both here and abroad. Tsotsi was the one remarkable movie that cleared all the hurdles and claimed the best foreign movie Oscar in 2005. Perhaps there is scope for this in future titles.

Movie poster

If you live in a city, the portrayal of your city in a film is likely to appeal. Everyone is ready to express an opinion on what the director should have seen or captured. Everyone is an expert on their city and, as mentioned, it gives one a thrill when you see a familiar landscape, street scene or skyscraper up on the big movie screen or even the small home TV screen. The story line becomes incidental to the location, scene and place. The author is to be congratulated on negotiating a large subject, refining some interesting questions and developing a methodology to test assumptions.

This study has been published in the USA and is part of a series of books called Screening Spaces edited by Pamela Robertson Wojcik of the University of Nortre Dame, Indiana. The series showcases "interdisciplinary books that explore multiple and various intersections of space, place and screen cultures". I wondered why a study on Johannesburg film and filmgoers should have been appreciated and published in the USA and not in South Africa. A local publisher and editor should have worked with the author to make the book available locally.

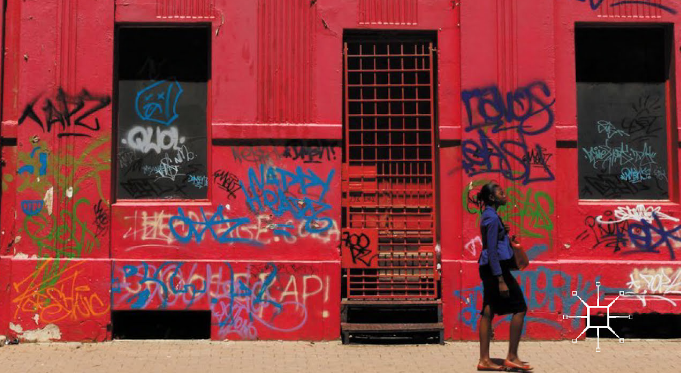

Alas the quality of the illustrations in a book about a visual medium is laughable. Small little black and white photographs of stills from critical films detracts from rather than enhances the text. Unfortunately, foreign publication puts the price way beyond South African pockets. This means that the book may be acquired by university libraries but it will not enjoy a wide circulation. This is a shame. The book is written for a specialist academic niche readership but nonetheless makes an impressive contribution to scholarship of the city. I would have liked it to achieve a wider impact through a book structured appeal at a more popular level.

Parker needs to seize the opportunity to write about the architecture of the cinema in Johannesburg and to show how the movie houses of the city impacted on the minds and imaginations of generations of city residents. Where is Commissioner Street in the story of film in Johannesburg? Perhaps more important than Johannesburg films changing perception and practice, is the influence of film in general in the city (American, British, French etc. and across all categories). This cries out for study. I agree this is a city shaped by the movies during the course of its history but it was not just Johannesburg film that matters.

I recommend this book as an addition to a Johannesburg focus library. It is a new and little studied dimension.

2017 Guide Price: The book may be purchased at Love Books in Melville for R1500. It can also be purchased online as an ebook at $69.99 or a hard cover at $99.99.

I thank the author for lending me her copy of her book.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.