Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Most commentaries on Johannesburg of the decade of the thirties takes 1936 and the city's fiftieth birthday as the year for reflection and anticipation. See, for example, the Star Newspaper's popular history, Like it Was. Johannesburg A Sunshine City Built on Gold (1931) is an unusual publication that takes us back to the start of the decade to discover Johannesburg.

Book Cover

What was Johannesburg like in 1931? One source of information is this small 56 page booklet issued in that year by the Johannesburg Publicity Association and the SA Railways and Harbours (a national state department). It was meant to promote tourism to Johannesburg specifically and South Africa in general in an upmarket authoritative way to the elegant visitor or potential immigrant. The new Johannesburg Station (Leith and Moerdyk) was being built, the foundation stone was laid in 1928, but it did not open until 1932, when arriving train passengers saw the city for the first time as they came up the marble steps and gasped when they viewed fashionable people going shopping in Eloff Street. This is a small promotional book that might have fitted into your leather valise to be read on a sea voyage out to South Africa by mail ship.

Park Station (SA Builder Magazine)

It's all about why the visitor should come to Johannesburg for a visit or why the immigrant should make a new home here, but it's hardly the sort of book one would tuck under into a backpack to guide a visit to the sights of the city. Rough guide or Lonely Planet it was not! There is no map, although the a map of Johannesburg's transport network and suburbs was also available (click here to view the 1931 Johannesburg transport map). Its opening chapter is Johannesburg as a "holiday centre ", a rather optimistic possibility but in 1931, colonial, provincial, brash, young Johannesburg was on a selling mission to the world.

This small book has the charm of the era of the thirties, a decade when Johannesburg changed speedily and embraced modernity and overseas culture. The subtext of such guides, published by our city, was actually to sell the city to its own citizens and make them look about in wonder and feel gratitude for the many amenities and comforts of their modern urban existence provided by the City Council. It’s dense with information. The population of the city was 342 000. Water cost 4s. 2d. per 1000 gallons, there were 200 tram cars, the fire department protected the city expanse of 82 square miles with the most modern of fire engines, Ellis Park Swimming bath could accommodate 3000 spectators, 15 500 people borrowed books from the Public Library.

Johannesburg Public Library (SA Builder Magazine)

The leading chapter is all about Johannesburg at the geographical centre of the Witwatersrand, at that time "the world's greatest gold field", and there is no doubt that the making of the modern city was possible because of the success of the gold mining industry, based upon cheap migrant black labour, cutting edge technology and skilled but racially conscious white miners. It was an industry that was both capital and labour intensive. For the city of Johannesburg, gold mining permeated all. One only has to move towards Eloff St extension to encounter the yellow fine sand mine dumps creeping towards the centre of the town and rising as man-made mountains.

A mine dump to the south of the city in 2012 (The Heritage Portal)

By 1930 the cumulative value of gold of the Witwatersrand from 1886 topped £1 billion. The wealth of city was firmly anchored in gold, and by 1931 the geologists knew that the dip and the line of the reefs was extensive and waiting for exploration, mapping and exploitation. The future of Johannesburg was assured (though a Star survey of 1936 revealed that respondents thought that "Johannesburg was probably here to stay”) despite the lack of a substantial local water supply. The early thirties saw drought conditions but the water problem was solved by the Rand Water Board's construction of the Barrage on the Vaal River. Johannesburg in 1931 had a coat of arms, in green and gold that reflected the mining history of the city with the 3 ore crushing stamps called dollies and the city's motto was Fortiter et Recte (with Valour and Justice).

One is struck by the boundless energy of the people of Johannesburg in the thirties. It was a youthful city that drew immigrants from the countryside and from abroad. It was a city that prided itself on education. No technical or engineering problem was beyond solution whether in mining, water or transport.

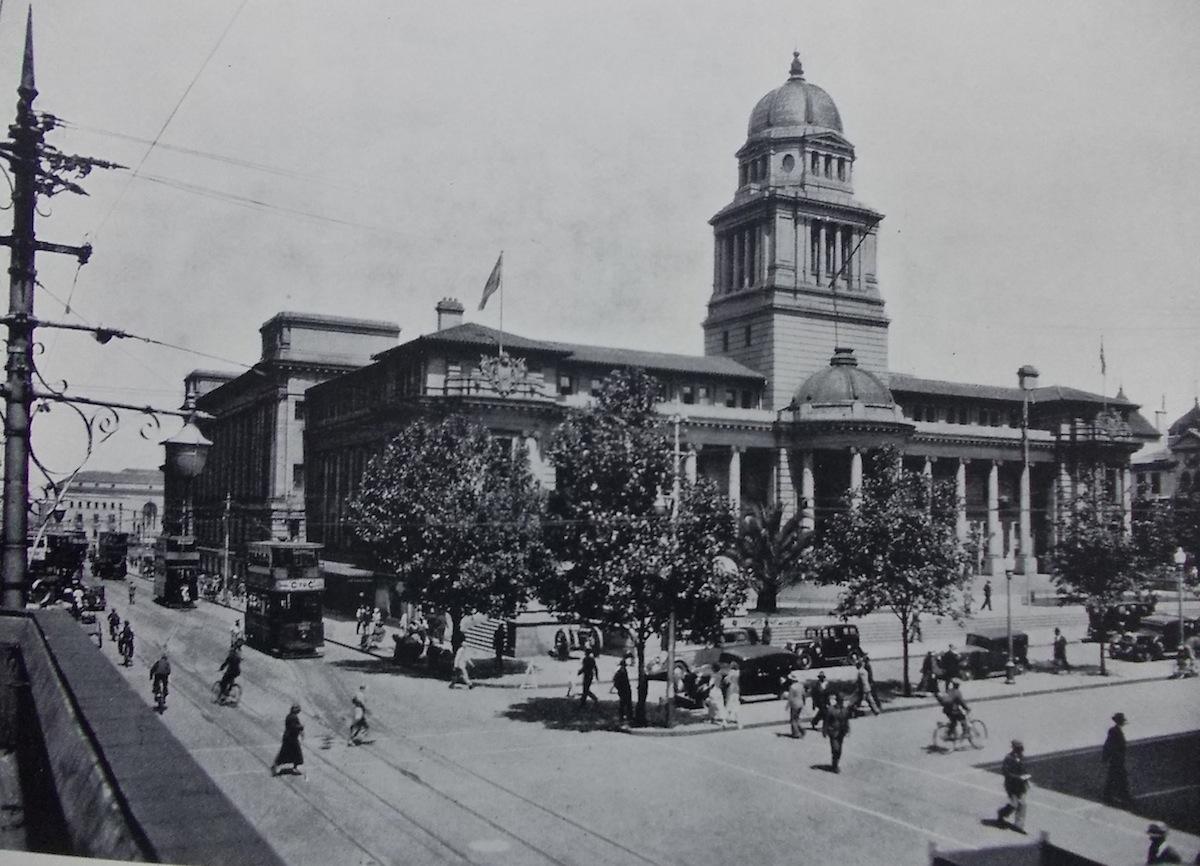

The modernity of Johannesburg of 1931, when the city was 45 years old, was what people talked about. In 1931 Johannesburg was described as "the miracle of empire" and a "wonder city of the world", with its gold mining industry, its thrusting self-conscious brashness and an appealing highveld climate. English speaking South Africans were proud to be part of the British Empire and called England "home ". Achieving city status in 1928, Johannesburg had arrived at a state of permanence with its pompous imperial city hall and a solidly English looking stone cathedral announcing its civic status. It had a rateable value of £62 million and a population of 342 000 (1931 was a census year). It was a city that was contained with a single central town centre with new affluent suburbs emerging to the north. Our quaint publicity brochure promotes the city as a holiday centre, a modern city, an educational centre, a financial hub and a sporting Mecca. The nearly 90 sepia toned photographs provide an excellent record.

Old photo of City Hall

Johannesburg of 1931 feels a familiar place in so many ways. The fundamental infrastructure was in place: Ellis Park for swimming or rugby, the City Hall, St Mary's Cathedral, the Art Gallery, Wits University, the Zoo, the Supreme Court and the Union Observatory with its fine 26 1/2 imported telescope were all functioning entities. The principal clubs were the Rand Club, the Union Club and the Country Club in Auckland Park. The Rand Regiments memorial and the Cenotaph honoured the war dead. Shopping in the central city department stores offered the latest styles and fashions. Roedean, St John's College, King Edward School, Jeppe Boys, Parktown High Schools and Johannesburg Girls High were all places of quality education whether private or public. You relaxed at the Zoo Lake or in Joubert Park or went to the races at Turfontein. Alternatively you could choose to be amused and entertained at the Empire Theatre, the New Bijou (described as a super cinema) or the nearby Orpheum offered a twice nightly bio-vaudeville programme. The Plaza cinema (the architects were Kallenbach, Kennedy and Furner) is described as "a new- erected and luxuriously furnished cinema".

Rand Club and Union Club (Johannesburg: A Sunshine City Built on Gold)

St Agnes House and Colonnade Roedean School (SA Builder Magazine)

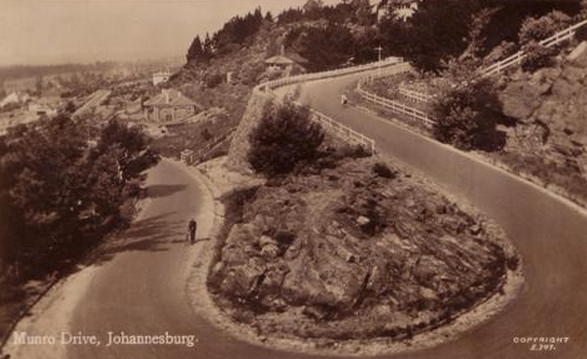

Transport was key to Johannesburg's expansion. South African Railways in 1931 bought two new narrow gauge steam locomotives. But what really made a difference to Johannesburg was the coming of the automobile as it meant good tarred roads were a priority and the northern suburbs of bungalow style houses with generous gardens could be developed in the thirties in Houghton, Saxonwold, Parkview, Parkwood. it was the Model T Ford or equivalent that made it possible for affluent families to acquire Erven and build their generous size homes on the veld. Access was then down Jan Smuts or Oxford Road or out on Louis Botha Avenue. Munro Drive had been cut through the Houghton ridge linking Upper and Lower Houghton and making possible the development of the thirties mansions of Lower Houghton.

An old postcard of Munro Drive

If you had spare cash in your pocket you could choose a British or American car in the Motor Hall of the Witwatersrand Show. The choice was wide. Motor Town had already appeared as a distinct segment of downtown. There is one photo of cars moving down Simmonds Street; there is no congestion, pedestrians and bicycles mingle with the cars. The automobile was still a novelty but there was a growing market and by 1929 General Motors had sold 25 000 Chevrolets built at their Port Elizabeth assembly plant. Robots had appeared and the horse and cart common a couple of decades earlier had all but disappeared. Rand Airport opened in Germiston in 1931 and an Imperial Airways passenger service, London to Cape Town, commenced in 1931. There is an unusual Pathè movie news clip of an aerial view over Johannesburg from a small plane, taken in 1931 (click here to view). The first regular airmail postal service was yet a year away as it was introduced in 1932.

The 90 odd sepia toned black and white photographs give a wonderful period feel of the comfortable life that it was possible for the affluent and successful middle classes to lead by the thirties. New Suburbs spread in all directions. This young city on the veld was an orderly place, effectively managed by a City Council. George Nelson was mayor in 1930 to 1931 and the very public spirited and popular DF Corlett took up the mayoralty for 1931 to 1932. Johannesburg Government was financially stable and a loan floated in London in 1930 of £1 million was heavily oversubscribed.

DF Corlett

Johannesburg in 1931 was on the rise towards becoming an Art Deco city of note but of course at the time that was neither anticipated or described in those terms. But in 1931 the confidence of this predominantly or perhaps that should be ostensibly white colonial city, existed comparable to Melbourne or Toronto. In 1931 only 128 tickeys or 3 penny coins were minted. The 1931 tickey is perhaps the rarest of coins of the Union of South Africa (remember there were 12 pennies in a shilling and 20 shillings equalled a pound). Doctors and professionals set their fees in guineas, ie 21 shillings, though there was no guinea coin. The closest you would get would be a golden sovereign worth a pound with George V's head and today a coin quoted at R4 604.80 on the Internet (or US $358 )

What about the national scene? South Africa acquired Dominion status in 1931, that is, it was a self-governing British Dominion with the passage of the Statute of Westminster. The Prime Minister was General J M Hertzog, who had defeated Smuts in the aftermath of the labour troubles of the early twenties and he went on to form the PACT government. It was only in the wake of the 1932 economic crisis that a coalition government between Hertzog and Smuts was formed. In 1931 the new Governor General in South Africa was appointed. He was George Villiers, Earl of Clarendon and it was he who gave his name to the thoroughfare collecting the city with Louis Botha Avenue, Clarendon Circle.

Clarendon Circle (Lost Johannesburg)

Internationally the world was set for trouble in 1931 with the depression biting deep, banks failing, international trade shrinking and unemployment rising. Politically the world moved towards the right, greater extremism brought the national socialists under Hitler to power in Germany. In Britain economic crisis in 1931 forced the country off the gold standard and the Labour government mutated into a national coalition government though with Ramsay Macdonald still remaining as Prime Minister. The world became a less safe and secure place in that decade with people on the move to escape repression and the many ominous signs. In 1931 Gandhi went to Britain to attend the 2nd round table conference pushing towards Indian independence from the British Empire. He did not succeed at that date but he captured the public's imagination in the UK.

What is then missing from our promotional guide of Johannesburg? There is no mention that 1931 was a depression year and although South Africa's economy did not contract as sharply as that of the USA or Britain, agriculture and mining were indeed hit and unemployment rose. In 1931, the Carnegie Commission produced its multi volume report on the so called "poor white" problem and this showed that one third of Afrikaners lived in dire poverty and the solution to that lay in urbanization and a consciously Afrikaner nationalist political and economic drive. It was only late in 1932 that South Africa went off the gold standard, the price of gold rose to $35 an ounce, effectively the currency devalued in line with the British pound. It was the right decision and the country was set for a new phase of mining expansion and a building bonanza and Johannesburg benefitted.

However, in 1931, the Africanness of the city was defined only by its unique gold mining past. There's no recognition of any possible social problems, poverty, colour divisions, segregation, an emerging Kliptown or Sophiatown. There is not a mention of 1931 being the year when a competition was held for the design of a new African township settlement, based on garden city principles, for Orlando (the Kallenbach practice won the competition for the design of this new African township to be).

In 1931, our guide comments that "native and coloured races supplied all the unskilled and even the semi-skilled labour demands of South Africa" with the Europeans being the skilled workers. In 1931, native and coloured people in Johannesburg outnumbered the so-called Europeans four to one. Anyone giving any thought to this stark information would ask ‘Where did all these people live?’. Well poorer people did live in mixed areas such as Sophiatown and in 1934 the combined population of Sophiatown, Martindale and Newclare was 26 000. The City Council was on a mission to clear the slumyards of the inner city, the shanties and shacks and slums so painstakingly described by Ellen Hellman in the thirties. The development of the black residential areas of the city also then dates from the thirties with the Council taking responsibility to rehouse people in what they regarded as better accommodation.

There is also the documentary value of this small guide as it also carries photographs of places and buildings long since demolished: the Murray Gordon Mansions in Westcliff, the Municipal Market of Newtown is now in Kazerne, the old Carlton Hotel was demolished as was the Lutjens Langham, the Union Club is there but it's now residential accommodation, Johannesburg High school for Girls' no longer exists and its 1912 Queen Anne style building demolished. Today Barnato Park High School for boys and girls reflects the new demographics of Hillbrow and Berea.

Old Carlton Hotel (Meet Me at the Carlton)

Johannesburg in 1931 was glamorous, vibrant, exciting and an exacting place and at that point shifting from the frontier town of the Rand Pioneers to becoming a settled society with sharp class, social, racial and economic strata bedding down in a town where rich rubbed shoulders with the poor and all was not quite as our 1931 guide tried so eagerly to present.

This is the ideal book to revisit the city of another era and to tackle a photographic then and now comparison. There is much that you will recognize and some buildings that joined the Lost Johannesburg category in the decades that followed. Arm yourself with this little guide book and your own camera to capture Johannesburg no longer to be presented as the colonial hub of Southern Africa but as the premier African city of a post-apartheid country.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.