Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

When Johannesburg’s august Mayor, Harry Graumann (later Sir Harry), welcomed the Duke and Duchess of Connaught on 28 November 1910 he presented the Royal couple – who had come to South Africa to open the first Union Parliament – with a lavish commemorative book. This described the Town Engineer’s duties in terms of roads, parks, gas, electricity provision and other grand projects, but there was not a word about sewage, such were the Edwardian sensitivities to this delicate subject. Yet the disposal of human waste has determined the size and success of cities for millennia. Delta Park owes its existence to the expansion of Johannesburg’s sewage scheme during the 1930s when rural farmland on the outskirts of the city was transformed into the Delta Sewage Disposal Works.

Johannesburg is situated on the Witwatersrand watershed and rivers flow either to the south (into the Klip River, thence into the Vaal River, and eventually into the Atlantic Ocean) or to the north (feeding into the Crocodile River, the Limpopo River and disemboguing into the Indian Ocean). The city is somewhat unusual in always having separated waste-water (including sewage) from storm-water. Until a Town Engineer’s Department was established in 1902 after the South African War, sewage was collected in tarred buckets and removed beyond the town’s boundaries by horse-drawn night-soil carts to be used as fertilizer on neighbouring farms. Naturally, disease was a regular hazard.

Between 1902 and 1910 a very large gravity-fed sewage scheme (at a cost then of £335 000) was constructed for removing sewage from the city centre and its southern areas to Klipspruit, a council-owned farm on which the largest disposal works in South Africa were built. Over the years, the Klipspruit system was regularly updated and enlarged, and it remains in use today.

Dealing with sewage on the northern side of the watershed was more difficult. The geology of many parts of Johannesburg is not suitable for septic tanks and well into the 20th century night-soil collection in suburbia was still common, the carts depositing their daily loads into a series of intakes along the main Klipspruit sewer. But a northern scheme became imperative as the population of Johannesburg burgeoned northwards. The task of designing it fell to the City Engineer, Dr Ernest John Hamlin (known as ‘E.J.’) and a number of his colleagues, particularly B.L. Loffell (later City Engineer), H. Wilson, E.G. White and J.R. Gaillard.

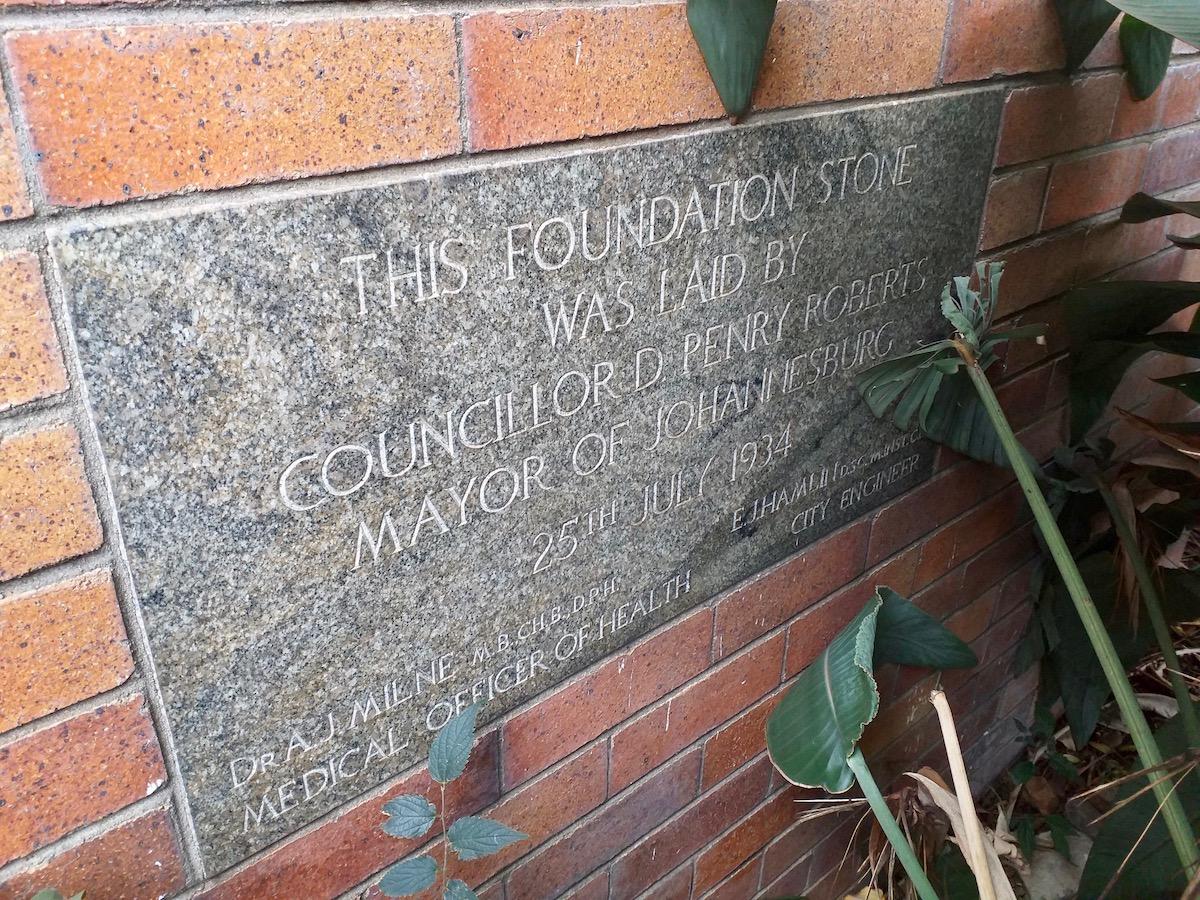

Hamlin's name appears on the foundation stone (bottom right) of the Delta Sewage Disposal Works (The Heritage Portal)

Hamlin is among South Africa’s most eminent engineers. Born in Bristol in 1887, he studied civil engineering at the University of Bristol and emigrated to South Africa in 1911. He took up an appointment as Lecturer in Civil Engineering at the South African College in Cape Town (after 1916, the University). After two years of lecturing, in 1913 he became Town Engineer of Stellenbosch, a position he held until 1927. Hamlin provided Stellenbosch with a modern sewage scheme that did not detract from the town’s pleasant ambience. In addition, he thoroughly researched the more deleterious effects of the local alcohol industry – distillery effluents and river pollution – in order to mitigate them. During this period, he obtained a D.Sc. from the University of Bristol; in 1922 he was elected Fellow of the Royal Society of South Africa; and over time he became prominent in numerous professional engineering societies in South Africa and abroad.

From Stellenbosch, Hamlin moved on to tackle the far larger and more complex city of Johannesburg. First appointed as Assistant City Engineer, he became City Engineer in 1932, holding this position until his retirement in 1947. In 1927, the year that Hamlin arrived in Johannesburg, the decision was taken to extend waterborne sewerage to the northern suburbs using the small natural drainage basins of four north-flowing streams. Gravity-fed plants were established, and Hamlin gave them Classical-sounding names (denoting A, B, C, D) that would not prejudice the neighbouring suburbs by association. All are closed today. They were Antea (the smallest on the west, serving Industria township), Bruma (on the east, currently a riverside shopping mall), Cydna (on the north-east, now the Melrose Bird Sanctuary) and Delta (on the north-west, today an environmental education centre and public park). These four schemes, together with the network of sewerage reticulation that had to be laid throughout the suburbs, were constructed during the Depression of the 1930s and were capital projects and poverty relief endeavours using only ‘poor white’, rather than black African, labour. Between 1932 and 1945 Hamlin’s department laid more than 1100 km of reticulation, often overcoming considerable engineering and design challenges.

A recent photo of the Delta Environmental Centre (Jane Carruthers)

The Art Deco Entrance (The Heritage Portal)

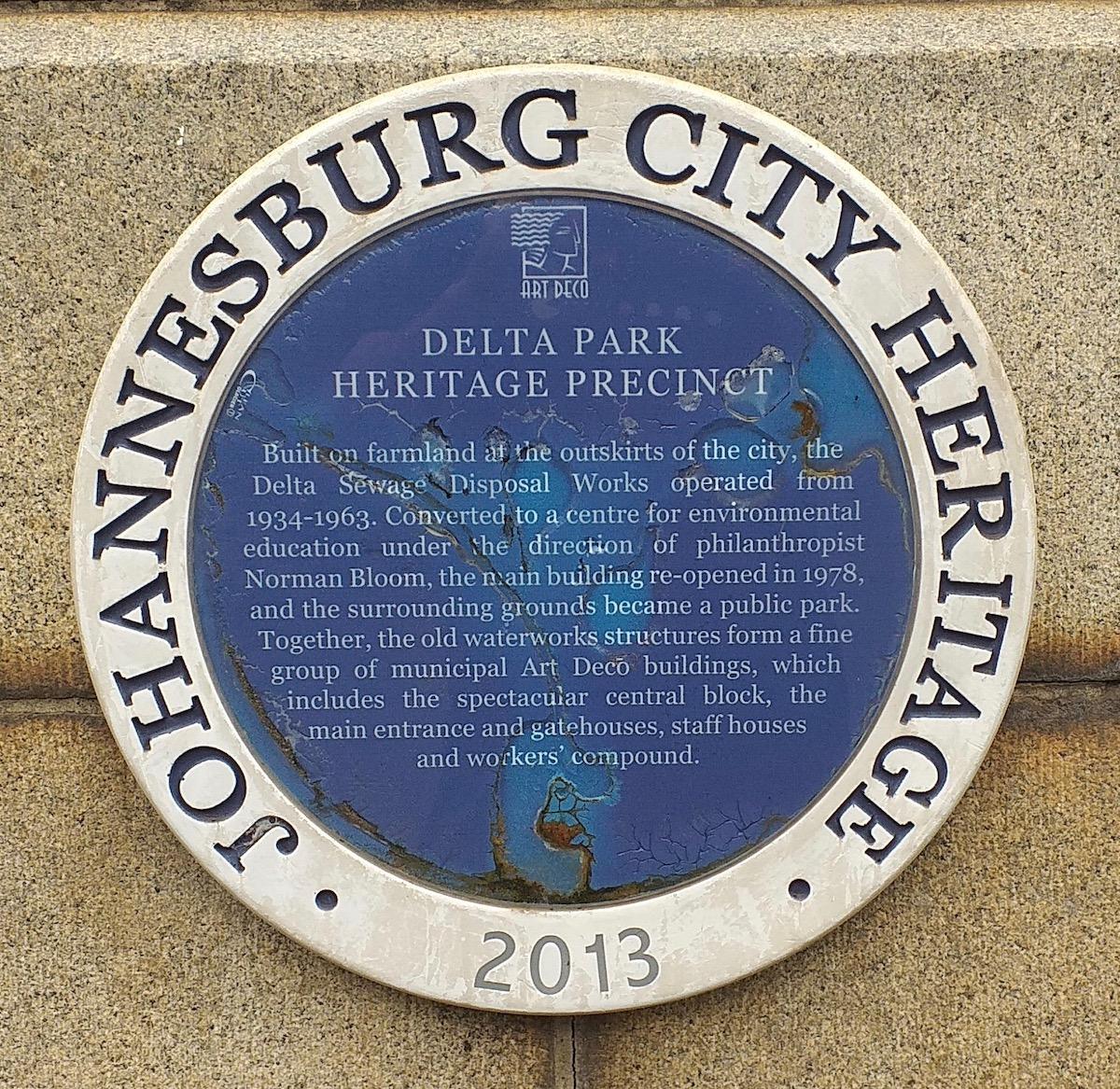

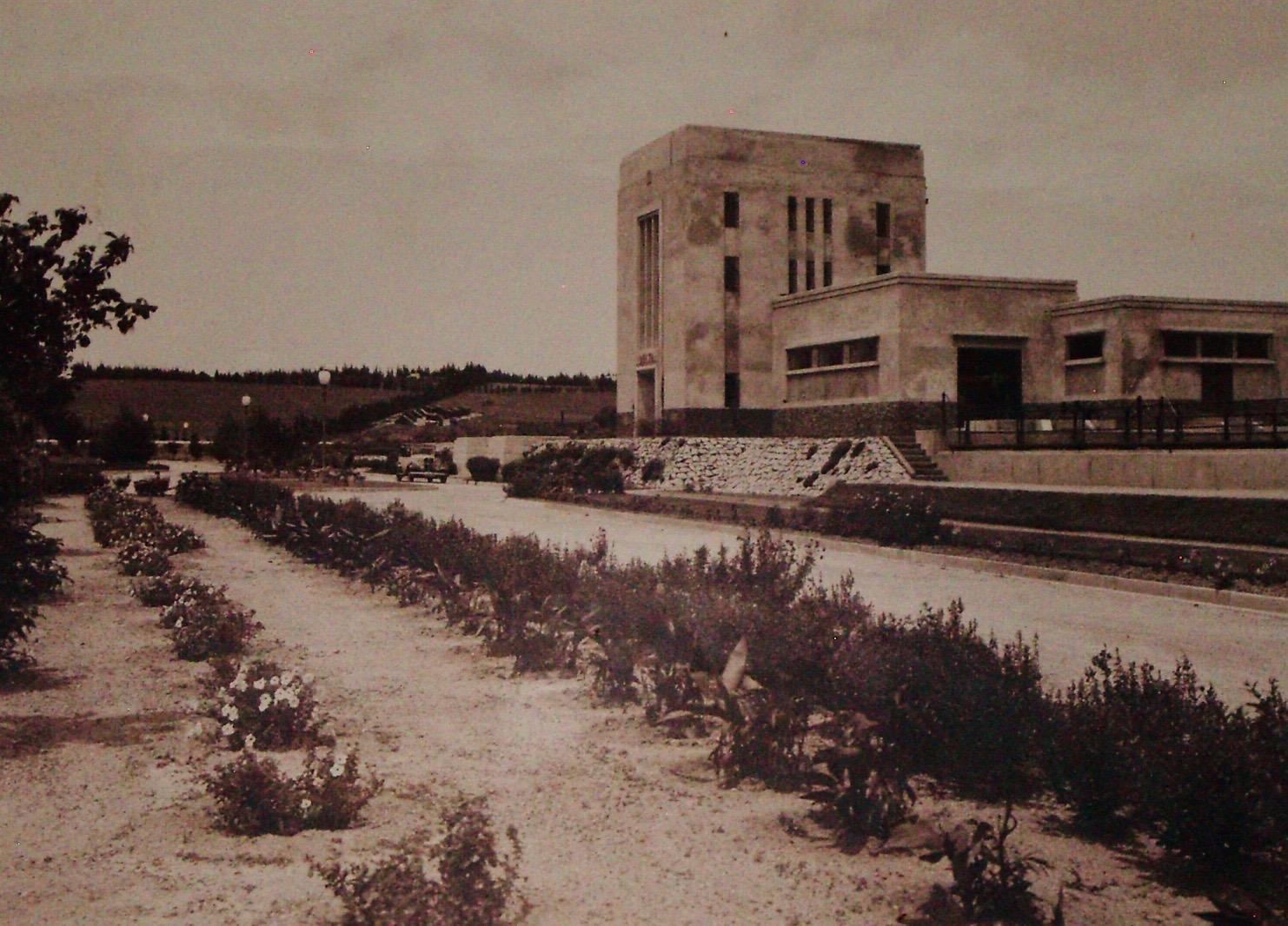

The most interesting of the four schemes was Delta, planned between 1932 and 1934 to deal initially with 4.5 million litres of sewage a day and to serve a population of 35 000 living in the areas of Parkview and nearby suburbs. A network of smaller sewerage pipes fed into the main sewer leading directly to Delta, where the city had acquired a large area (about 110 ha) of open land close to the suburbs of Craighall, Linden and Blairgowrie along a small stream that flows into the Braamfontein Spruit. The Art Deco building that housed the sewage works (and cost £13 500), with its foundation stone laid in July 1934, was extremely handsome – it has been declared a Heritage Building. Imposing, solid, square, geometric but elegant in shape, it now stands proud in the large open area epitomising the self-confident, progressive, and modern international building style of the 1930s.

The building received a blue plaque from the City of Johannesburg in 2013 (The Heritage Portal)

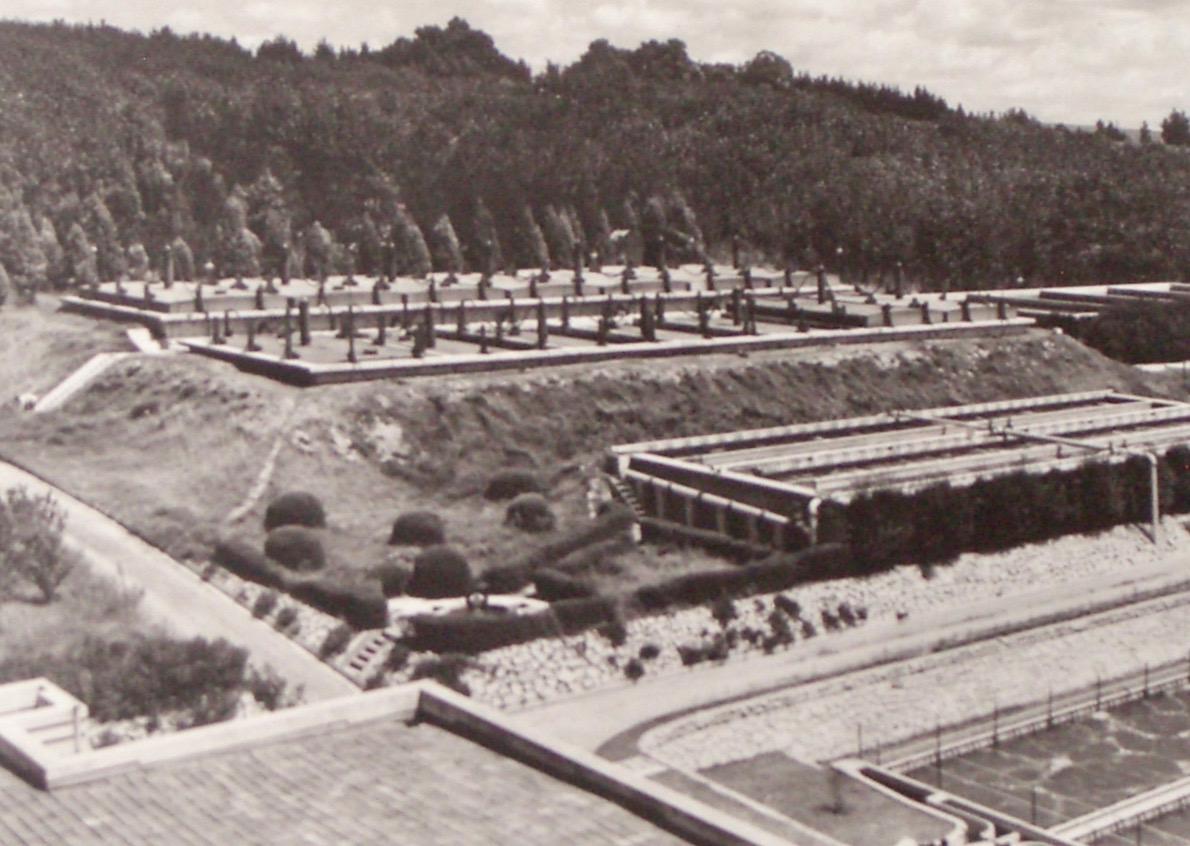

Not only was the Delta building unusual for such public works, but the method of treating the sewage when the plant opened in April 1935 was unique in South Africa for its time. It was innovative international technology especially adapted, after experimentation, for Delta. The first stage in the process was to use sorting screens to remove, by hand, any debris that might clog machinery. Thereafter, the sewage flowed into tanks where large particles of sand and grit settled to the bottom and were removed by hoppers beneath the tanks. In the third stage organic material in suspension was moved into sedimentation tanks where some of the suspended solids were removed as sludge. Because only about half the organic matter could be removed mechanically, Delta used a pioneering process called ‘activated sludge’ – a process in which gelatinous sludge particles (known as ‘floc’) were suspended in an aeration tank and supplied with oxygen. Organic matter was absorbed by the floc and converted into harmless gasses and by-products. A microbiological process then converted the sludge to methane, carbon dioxide, and ‘digested sludge’, an inoffensive humus-like material. In the final process the digested sludge was placed outdoors on sand beds and the water percolated into the ground or evaporated. At Delta, terraces of these sand beds were laid out on the north of the building. Any remaining dry sludge was used as fertiliser. Because of the unusual processes used at Delta, Hamlin and his colleagues presented and published academic papers on this type of treament that were well received internationally.

Sedimentation tanks at Delta

Delta sand settling beds to the north of the building

The building housed the sorting screens, the detritus pit and sedimentation tanks, the machinery rooms, and the general offices. Much of the complex machinery was designed and constructed by Hamlin’s department. The switchboard with its controls and recording instruments was state-of-the-art and could be operated remotely. There was ecological recycling as methane gas from the digestion tanks was collected and used as fuel for a gas engine alternator that generated 80 per cent of the electricity needed for the air compressors and for a ventilation system in the tank room. Waste heat was used for heating the crude sludge entering the digestion tanks. The City Council maintained a small herd of dairy cows on Delta and allowed a few private farmers to make use of the well fertilised grazing on council ground.

The construction of the Delta works proceeded along with the reticulation system. The huge excavation project began in October 1933. Some 17 000 cubic metres of earth were moved, of which 2 000 cubic metres consisted of solid granite. Part of the excavated material was used for raising the road from the entrance to the building and some was utilised for levelling the site for the Delta building and the terrace in front of it. The builders were Messrs Johnston and Stronach (Pty) Ltd.

Opening of the Delta Sewage Works 1934

Wartime stringencies caused engineers to think about other economic benefits of Johannesburg’s sewage farms. In 1941 a plantation of Deltoida poplars Populus deltoides was started at Delta. The timber from these deciduous, extremely fast-growing, Eastern Cottonwoods was highly suitable for matches and the city council hoped that it would not be long before the timber could be sold for this purpose. Many of these trees, which have a highly invasive root system, still grow on the Delta property. Another experiment was done with soap and grease-making. A combination of the hard water of Johannesburg, together with the fact that many of its people have a high-fat diet and dispose of this fat and grease in the sewage system, means that Johannesburg’s sewage has an extremely high soap and grease content. During the war studies were done on how to recover this grease and use it commercially as soap and engine grease, but in the end, the project came to nought, as did another project to manufacture cyanide from sludge gas.

After only four years Delta had reached its optimum load of 18 million litres of sewage a day, and it was expanded almost every year, continuing to work well for a decade. After the war, the boom continued and suburban development leapfrogged to the north over Bruma, Cydna, and Delta, which were now surrounded by housing. But Hamlin had already made his plans. In 1946, a year before his retirement, the City Engineer had begun designing a huge disposal works to the north, where the rivers of the northern Witwatersrand converge into one drainage system into the Crocodile River. Hamlin envisaged that, being a great distance away from the urban area, with plenty of available space and by using modern biological treatment of sewage, the Northern Disposal Works would serve northern Johannesburg for many decades to come. Together with the constant upgrading of Klipspruit on the south which had been well sited from the start, Johannesburg’s sewage problems would be ended. In the event, Hamlin’s vision has come to pass. But the construction of the massive Diepsloot project, with its enormous length of pipeline, which required both bridges and tunnelling to keep its gravity-feeding at the optimum, was extremely expensive and would take a long time to construct. In 1951 the design of Northern Disposal Works was finalised, and it was only in 1959 that these works began to accept any volume of sewage from the other treatment plants.

For many years, Antea, Bruma, Cydna, and Delta had to be upgraded piecemeal and as cheaply as possible until the Northern Disposal Works came onstream. Until the time for closing the Delta plant came, expansion was frenetic and ongoing. In 1952 a diversionary sewer had to be constructed to take some of Delta’s sewage to Klipspruit and the weirs on the activated sludge settling tanks had to be raised. By 1955 the position was critical as all the sewage plants in the north were treating far more than they were designed for. Indeed, it was hoped that Delta could close by the end of that year so desperately overloaded had that situation become. Exacerbating the position was the inept construction of the first of the new biological filters which had been built while many of the city’s officials were still away at war. Delta’s problems were compounded by the use of a dolomitic aggregate in some of the main sewerage pipes which began to corrode as a result. Each year the Northern Disposal Works took more of the sewage from the four small works which had now seen some thirty years of service. But they were still needed, and they continued to operate, especially as the reticulation of Craighall, Blairgowrie and parts of the newly established town of Randburg (1959) neared completion.

The engineers were worried too, because for some reason which they could not account for, Delta was being inundated with far too much fresh water. Either it was ground water which was infiltrating the plant, or it was the illegal addition of stormwater, but wherever it came from, it was increasing the intake of the plant to twice its maximum capacity in the rainy season. Making matters worse was the invention of synthetic detergent at this time, which may well have improved the cleanliness of laundry, but totally changed the chemical composition of sewage as a result. By 1961 Delta was experiencing a serious foaming problem which was insoluble, but which was held at bay with the use of daily surface hosing and the use of anti-foaming agents.

The Northern Disposal Works was expressly planned to be as far as possible from any municipal boundary or population node and Hamlin could never have imagined that the upmarket Dainfern residential development would, in time, nestle snugly beneath what has been called the ‘poo pipe’, sharing its shelter with the huge informal African settlement of Diepsloot. In use from the late 1950s when reticulation from the four small schemes was almost complete, this (with modifications) is still the main sewer for northern Johannesburg, its complexity leading to its inclusion as one of the ‘Seven wonders of civil engineering in South Africa’.

The 'Poo Pipe' (Google Maps)

The final report of the City Engineer which refers to Delta is a poignant one: ‘The Delta works was the last activated sludge plant of any size in the Republic and its closure marks the end, for the time being, of activated sludge as a treatment process in this country except on small-scale works. This plant has played a large part in the investigational work into the diffused air process at highveld altitudes and its passing will be marked with regret. As economic conditions favour activated sludge for large plant, the process may be expected to reappear at some future date.’

Eventually all four of Hamlin’s smaller schemes were shut down and dismantled. At Delta, the sand beds were removed, the area levelled, kikuyu lawns planted, and the land was transferred to the municipal Parks and Recreation Department. With the ever-increasing density of the area, it soon became one of Johannesburg’s largest and most popular public open spaces with little physical trace of its previous incarnation. The building, purpose-built and thus architecturally unsuitable for easy rehabilitation, fell into disrepair. In the 1970s it was rescued by Norman Bloom, a Johannesburg philanthropist, who rented it from the city and established what has become the Delta Environmental Centre.

Another shot of the Delta Environmental Centre (The Heritage Portal)

Delta Park (The Heritage Portal)

Hamlin was more than a sewage engineer. An energetic man, a skilled manager and technical expert with a dominating personality, he was also actively involved in town planning. Shaping Johannesburg’s urban development, even its traffic flow, are among his other achievements. Hamlin Street in Highlands North was named for him by the Highlands North Investment Company in 1936. During the War, with his staff depleted, his personal responsibilities increased. With the commission of Lieutenant-Colonel, he became engineer advisor to the Witwatersrand Military Command, and in 1944 he was appointed Director of Housing, placed by Smuts in overall charge of planning housing and other infrastructural requirements for post-war South Africa. During his career, Hamlin contributed significantly to his profession. He published his research in leading journals, he built capacity among young engineers and he was a member of, and energetically supported, almost every possible allied professional institution, including the Royal Society of Health. After retiring from the City Council of Johannesburg he set up as a consultant and worked on various projects until his death on 19 April 1956.

About the author: Jane Carruthers is Professor Emeritus at the University of South Africa, elected Fellow of the Royal Society of South Africa and Member of the Academy of Science of South Africa. She has been awarded many international visiting research Fellowships, including at Cambridge University, the Australian National University and others. She is a former President of the International Consortium of Environmental History Organizations, the Southern African Historical Society, Chair of the Academic Board of the Rachel Carson Centre Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich, Editor-in-Chief of the South African Journal of Science, and recipient of the Distinguished Scholar Award from the American Society for Environmental History. She pioneered the discipline of environmental history in South Africa and her book, The Kruger National Park: A Social and Political History (1995) has become a standard reference worldwide. Her research interests are broad, and include environment history, national parks, the history of science, land reform, colonial art, ad comparative Australian-South African history. She is the author of numerous books, as well as many book chapters and articles in scholarly journals.

Thanks to: Librarian Ms C. Wilshire, Local Government Library, Greater Johannesburg Metro Council.

References

- Appelgryn, M.S, ‘Die ontwikkeling van plaaslike bestuur in Johannesburg, 1886-1899.’ Unpublished M.A., University of South Africa, 1971.

- Barnard, J.J., ’Factors affecting the anaerobic sewage sludge digestion process with specific reference to certain toxic phenomena.’ Ph.D., Unisa, 1973.

- Beirne, L.J., ed., Johannesburg Royal Presentation. Johannesburg: Town Council, 1910.

- Bodman, W., The North Flowing Rivers of the Central Witwatersrand. Johannesburg: The author, sponsored by CIBA-GEIGY, 1981.

- Call, S.T., ‘The sewage treatment service: Economies of scale and optimal industrial surcharge strategies.’ Ph.D. Indiana University, 1977.

- Carruthers, J. ‘Dainfern and Diepsloot: Environmental justice and environmental history in Johannesburg, South Africa’, Environmental Justice, 1(3), 2008, pp.121-125.

- Carruthers, J., ‘From sewage sludge to pleasant park: The Story of the Delta’s Disposal Works, 1934 to 1963.compiled for 25th Anniversary of Delta Environmental Centre 2000. http://deltaenviro.org.za/history/

- Carruthers, E.J., ‘The growth of local self-government in the peri-urban areas north of Johannesburg, 1939-1969’. Unpublished M.A., University of South Africa, 1980.

- Chipkin, C.M., Johannesburg Style: Architecture and Society, 1880s to 1960s. Cape Town; David Philip, 1993.

- Grant, G. and Flinn, T., Watershed Town: The History of the Johannesburg City Engineer’s Department. Johannesburg: City Council, 1992.

- Johannesburg City Council, Annual Reports of the City Engineer, 1930 to 1963.

- Kennedy, L., ‘A short history of Craighall and Craighall Park’. Unpublished paper presented at the Annual General Meeting of the Craighall Residents’ Association, November 1978.

- Marais Louw, J., When Johannesburg and I were Young. Johannesburg: Amagi Books, 1991.

- Van Vuren, J.P.J., Soil Fertility and Sewage: An Account of Pioneer Work in South Africa in the disposal of Town Wastes. London: Faber and Faber, 1949.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.